The House of Stuart

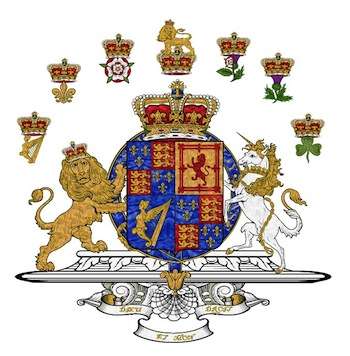

A Royal House of Scotland and later England and Ireland. Notable for the ascension to the throne of England of James VI of Scotland (thenceforth also James I of England) in 1603, following the death of his childless distant cousin Elizabeth I of The House of Tudor, thus creating the union of the crowns. Ruled until 1714, with a bit of a blip from 1649-1660 when first a Commonwealth (under the Rump Parliament) and then a Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell and briefly his son was in place instead, who for the sake of completeness are mentioned below.

Was called Stewart until Mary Queen of Scots changed the spelling (her French in-laws kept mispronouncing it).

James IV (1488-1513)

His father was killed in a rebellion when he was fifteen, and he did penance each Lent for the rest of life as he felt indirectly responsible.

His wife was Margaret Tudor, sister of Henry VIII of England, which gave his descendants a claim to the English throne.

An effective ruler and rather intellectual (he performed some surgery), he initially supported Perkin Warbeck, a male model who was a pretender to the English throne, before realising peace with his southern neighbour was better.

When the Italian Wars broke out (specifically the War of the League of Cambrai in 1508), Scotland had conflicting treaty obligations to both France and England. James eventually chose to support France and taking advantage of Henry VIII's absence, invaded England.

Got beaten by a girl, or rather Catherine of Aragon's army at the Battle of Flodden Field. Mainly due to some rather old school tactics, such as informing your enemy of your invasion several months in advance and fighting on the front line along with his men. He died in that battle, the last British monarch to die in a war. His body passed around various nobles and his head was used as a plaything. Flodden Field was also the last real battle in Britain involving spears and arrows.

James V (1513-1542)

Ascended to the throne when he was seventeen months old, after his father died at Flodden Field. Had many bastard children, including Lord John of Coldingham and James Stuart, Earl of Moray. His only surviving legitimate child was a daughter; at her birth, he is said to remarked, "[The Crown] came with a lass, and it will pass with a lass", referring to the marriage of Marjorie Bruce into the Stuart family. Mary averted this fate by marrying Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, her half-cousin through his mother (Lady Margaret Douglas) and a more distant cousin through his father (Matthew Stuart, Earl of Lennox).

Royal genetics are fun.

Mary I of Scotland, aka Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1567)

Became Queen at only six days old, when her father died of what was probably cholera, although the loss of the Battle of Solway Moss didn't help.

Having an infant as the leader of your country opens a lot of doors for less-than-honorable noblemen, so Mary's mother kept her little court safe in one of the harder to penetrate castles. About this time, Henry VIII asked to have his great-niece betrothed to his son, Edward, and thus unite their crowns a generation early, but Mary's mother, being French, said no. Henry VIII was rather insulted by this, and, when his "Rough Wooings" (read: attacks) didn't work, he snubbed Mary in his will, passing over her lawful claim to the throne.

Mary instead married into the French royal family, the House of Valois, and spent a brief time as Queen-Consort of France. After her husband died, she returned to her own kingdom of Scotland. While clever, Mary proved to be too impulsive and naive to deal with the factional politics in Scotland, was forced to abdicate in favor of her baby son (seeing a pattern here?) and eventually, as a perennial focus for Catholic conspiracies, was duly if reluctantly executed by her cousin, Elizabeth I.

James VI and I - 1603-1625 (Scotland 1567-1625)

Became King in Scotland at only 1 year old (his mother having been deposed) and had various regents, who may or may not have been Evil Chancellors. Three child monarchs for Scotland in a row...

After becoming King of England he hardly ever returned to Scotland, enjoying a far more extravagant lifestyle at the wealthier English court. Angry Catholics, fearful of greater repression from the new king tried to blow him up in 1605 in the Gunpowder Plot, which did not go well for them to say the least. James was liberal with money, running up massive debts, and was almost certainly involved in numerous homosexual relationships, which didn't help his popularity much. Traditional interpretations were harsh, seeing him as irresponsible and doing little more than storing up trouble for his successor but more recent analysis highlights his commitment to European peace, studious nature and successful reign in Scotland. Culture flourished round about this time, especially with some chap named Shakespeare being around. And he commissioned a particular translation of The Bible, that bears his name.

Had a fear that witches were trying to get him. Also wrote one of the first anti-smoking pamphlets. No, really.

Charles I - 1625-1649

Had what might charitably be described as a difficult reign.

Physically unimpressive (he was a very short man) and cursed with a speech impediment, Charles had it tough to begin with. Having to deal with several kingdoms while plagued with money troubles and religious strife which began decades prior to his reign would not have been easy for anyone, but unfortunately Charles' character made things a lot worse. He believed in the divine right of kings to rule and quickly grew angry at attempts from Parliament to exact more power in exchange for finances. He levied fines without Parliament, in a highly unpopular move, for 11 years from 1629-1640, until his religious problems caused him to recall it.

All three kingdoms under his rule had different Christian denominations as the majority: England was by this time identifiably Anglican (with many internal disputes among Church members about what that should mean), while Scotland was solidly Presbyterian and Ireland was Catholic. Charles' attempt to impose uniformity on the Scottish church caused them to rebel in what are called the Bishops' Wars. Needing additional funds he called Parliament, who after 11 years were inclined to be bitchy. His having a Catholic wife (whom he faithfully loved) at a time when there were rumors of massacres of Protestants in Ireland (in truth around 2-3000 were likely killed in the Irish revolt but this was widely inflated) didn't help matters. They demanded their authority be confirmed and increased, sentenced the King's chief minister to death and generally both sides riled each other up, until...

Fed up with their presumption of power, Charles marched into a sitting Parliament with his guards and assumed the Speaker's chair. This was an extraordinary act -- English monarchs had the legal power to do all this but they were expected, partly by custom and partly by their supposed understanding of the need to respect Parliament, to never do so. He attempted to arrest the ringleaders of the opposition cause, but they had escaped and he looked foolish, running away from London (which given Britain Is Only London was a mistake) raising his standard at Nottingham in 1642 -- so beginning the English Civil Wars. Parliament, and the country, was split in half between his supporters and opponents.

- Since then, the monarch has been banned from entering the House of Commons. For the State Opening of Parliament, a messenger known as 'Black Rod' is sent. The door is ceremonially slammed in his face when he approaches, so he bangs on it with his titular big stick. Then he's let in and invites the MPs to the Queen's Speech. Since at least the 1980s, republican Labour MP Dennis Skinner has made a habit of making a snarky remark in response, to which everyone else will laugh heartily; it's unclear if someone else will make a tradition of it after he leaves Parliament. Then they all get up and stroll--not process, but stroll--across the way to the House of Lords, which, as a sign of their independence, they enter talking loudly and making jokes.

To cut a very long story short, Charles lost the First Civil War and was imprisoned (in comfort) by 1646. As the victors tried to figure out what the hell to do next Charles refused to compromise (his Fatal Flaw) continuing to play sides against each other, drawing the Scots (who had fought against him) to renew the fight against Parliament in 1648. He lost again, and this time he had convinced his enemies that he could not be trusted and must be killed or he would simply keep raising armies to fight more wars (his enemies referred to him as "that man of blood"). As the Parliamentary forces divided themselves over the issue, Charles was tried for Tyranny and High Treason and executed on 30th January 1649. Charles notably managed to show more dignity and presence during his trial (where he lost his habitual stutter and refused to recognize the legitimacy of the court) than at any other point, asking for another coat when he prepared for his execution, so that the crowd would not mistake his shivering for fear. Was made a saint by the later Church of England. Charles made a difficult situation worse with his Fatal Flaw of refusing to accept the inevitable in the face of defeat, or compromise to head off trouble down the road. Like his father, he was an instinctive autocrat who had no intention of surrendering any of his power. Unlike his father, he had no understanding of how power actually worked, seemingly sincerely believing that the English people were required to succumb to his will.

Charles II - 1649 (de jure)/1660 (de facto)-1685

Declared in Scotland upon his father's death but not acknowledged elsewhere, he tried to regain the throne but was defeated comprehensively at Worcester in 1651, famously having to hide in a tree to escape – from which incident many pubs in Britain are still named the 'Royal Oak' to this day. With Ireland also under the control of Parliament, he lived on the Continent for many years. After the collapse of the English government following the death of Oliver Cromwell, Charles was invited to take the throne in 1660, in what is known as the Restoration of the Monarchy. Charles pardoned most for their rebellion but executed the regicides of his father, even posthumously for some. One of those executed, however, was a relatively moderate Puritan and former settler of the New England colonies named Sir Henry Vane who had argued against the execution of Charles I and seems to have somehow slipped through the cracks. Charles II was known as the Merry Monarch (a Boisterous Bruiser perhaps) for his colourful reign, a stark contrast to the Puritan regime that preceded him. Kept tensions in the Kingdoms under control to some extent, although the problems that had dethroned his father remained and he had some conflict with Parliament. Had twelve children from five mistresses, but left no legitimate issue -- was consequently succeeded as king by his openly-Catholic brother James. This was one of the major reasons for opposition to him in Parliament and even came close to igniting another civil war. May have converted to Catholicism on his deathbed, certainly he flirted with the idea and promised to promote it secretly (though how serious he was we cannot know) in exchange for French money. His last words concerned taking care of his favorite mistress.

Oliver Cromwell got dug up and posthumously executed for high treason. His severed head was originally placed on a spike as a warning to other 'traitors', and was eventually blown down; in a piece of (probably) accidental symbolism this happened around 1688 when the Glorious Revolution forced King Charles II's successor, James II, from power. It changed hands a few times afterwards but has since been re-buried in the grounds of Cromwell's old college (Sidney Sussex) at Cambridge University.

Charles' popularity was in part attributed to him staying in London when the Great Fire of London hit in 1666 and helping out with the firefighting (similar to how the Royal Family gained respect when they stuck around for the Blitz in 1940).

Paradise Lost was written during the reign of Charles II by John Milton, a Puritan republican. Also, the cheerfully scandalous atmosphere of King Charles' court produced a particular type of Play now known as Restoration Comedy. And around about this time Samuel Pepys was writing his famous diary.

James II and VII - 1685-1688 (-1690 in Ireland)

"I shall find a way to do my business without you!"

James was Catholic, which was a big no-no for the majority of his Kingdom. His reign was plagued with quarrels and eventually Parliament invited his son-in-law, the hero of international Protestantism William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Dutch provinces, to take the throne. James fled in the so-called Glorious or bloodless (a misnomer) revolution of 1688/89 and his last attempts with fighting in Ireland failed, notably at the Battle of the Boyne. Appears early on in Neal Stephenson's The Baroque Cycle, a little more than his more famous brother.

Both sides in The Troubles tended to harp on about his campaign in Ireland - the Republicans saw James as a tragic hero, the rightful King victimised for his faith. The Unionists, on the other hand, celebrated the victory of "good King Billy" over the Catholics, and adopted orange (from the Dutch House of Orange) as their colour.

James's ingratitude and contempt towards his Irish followers (and his abandonment of the country after the Battle of the Boyne, earning him the unenviable nickname Seamus an Chaca - 'James the Shit') has made his legacy in Ireland a bit muddled. While nationalist history tends to emphasise the justness of his cause, the focus is often less on James the man and more on the heroic Irish general Patrick Sarsfield, who kept up the fight for more than a year after James had fled.

The city of New York was specifically named after him (when he was the Duke of York), rather than after the English city of York directly. He also tried to bring a form of united colonial governance to some of the American colonies, the "Dominion of New England", but this was never popular at the time and was quickly scrapped by the new regime when he was overthrown.

William III and Mary II - Joint rulers (Mary 1689-1694, William 1689-1702):

For the Protestant Religion and the Liberty of England I Will Maintain—"I Will Maintain" being the motto of the House of Orange.

Universally known as just "William and Mary", theirs remains a unique shared reign, which lasted until Mary's death. Continued to fight on the continent but still unpopular in later years.

William was, technically, linked to the House of Stuart through his wife (he was a step-nephew of Charles II) but Jacobites (supporters of James II and his descendants) did not recognise it as part of the legitimate Stuart line which remained in exile in Continental Europe, and it is generally seen as part of the post-Stuart monarchy which led to the Hanoverians whose decendants remain on the throne to this day. In another case of 'interesting' royal genealogy, James II was both William's uncle and Mary's father.

Parliament's path to supremacy was back on track, meeting every year from hereon out. In particular, William and Mary were the first monarchs to be declared as such by Parliament, signifying how power had shifted. The Glorious Revolution saw the drawing up of the English Bill of Rights, forming the basis for the (unwritten) British Constitution and ultimately inspiring many of the precepts of the American Constitution (to say nothing of the precepts of the other ex-colonies that, to quote our article on Australian Politics "got a free British Political System" with independence).

Mary became pregnant shortly after her marriage to William, but she miscarried. Either that trauma or a subsequent illness rendered her infertile. As such, the Crown passed to Mary's younger sister, Anne.

Anne - 1702-1714:

Second daughter of James II, and Protestant. It was during her reign that the Act of Settlement 1701 passed the English Parliament, ensuring that only Protestants could inherit the throne, thus officially de-legitimising her younger half-brother (from her father's second marriage) James. This Act survives to this day and still provokes controversy. This combined with a failed Scottish scheme to set up a colony in Panama to convince England (including Wales by prior annexation) and Scotland to finally unite after 1707's Acts of Union as a single country with a single Crown and a single Parliament, rather than two countries with one monarch (the Scottish nobles had taken a financial bath and wanted to be compensated; the English were afraid Scotland would choose another successor and ally with France). By virtue of this, Anne remains technically the last Queen of England, and the last Queen of Scotland, as she became the first monarch of a united Kingdom of Great Britain[1].

Many British patriotic songs and sea shanties date from her reign, mainly due to the War of the Spanish Succession, including Over the Hills and Far Away and Spanish Ladies.

Notoriously, and the one thing for which she is now mostly remembered, she was pregnant no less than 18 times yet only one of her children survived infancy, and he died at age 11. Consequently the reign of the House of Stuarts ended after her death, and the crown was passed on to the closest Protestant relative: George I of The House of Hanover, bypassing over fifty closer relatives (virtually all of them Catholics).

There were several attempts on the part of the 'Jacobite pretenders' -- Anne's half-brother James "III and VIII" (known as 'The Old Pretender') and his own son Charles "III" (a.k.a. Bonnie Prince Charlie, 'The Young Pretender') -- to take back the British crown. But when Charles died without any children and his brother Henry became a Cardinal, the legitimate line of the House of Stuart in exile effectively ended. Their claim to the throne continued through their closest relatives amongst other European noble houses, and was recognized as such by Jacobites, although none made good on the claims bestowed on them.

- Part 2 of the mini-series Gunpowder, Treason and Plot charts James I's (played by Robert Carlyle) ascension to the English throne and climaxes with the Gunpowder plot.

- To Kill A King about the trial of Charles I, played by Rupert Everett. Tim Roth played Oliver Cromwell.

- ↑ (See also: Britain Versus the UK)