Britain Versus the UK

Britain...Great Britain...The UK...The United Kingdom...The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland...The British Isles...England...

There is no nation in the world called "Britain" or "Great Britain."

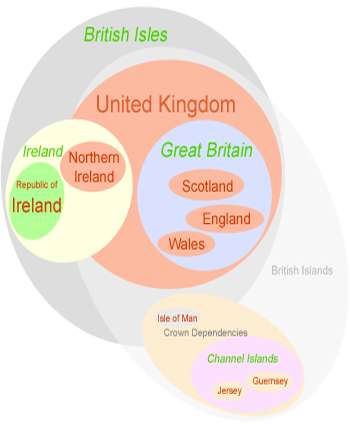

This may sound strange and contrary, but it's true. There was once a nation-state of just Great Britain, but not for over 200 years now; there has been no nation-state called England for over 300. The United Kingdom as it exists in modern times is a compound of four member countries. Yet it is a matter of much frustration to many of their residents – in particular those from the nation's smaller constituent countries, but to English people too – that the terms "Britain", "Great Britain" and "United Kingdom" remain not only often synonymous with each other but, most annoyingly, with "England" in the minds of foreigners (and many ignorant natives...). The distinctions between all these frequently overlapping and vaguely similar-sounding names can be lost on many people, meaning the different terms are frequently used interchangeably, but the political and cultural structure of the kingdom is rather more complicated than that. At present, it is thus (see here for a visual representation):

- The British Isles (a geographical term) are a collection of islands off the north-west coast of continental Europe, upon which sit two sovereign states - the Republic of Ireland, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland - and also the Isle of Man (see below), which has a peculiar status all its own.[1] As a geographic term, it includes the area of the Republic of Ireland (which is not 'British'), without implying any territorial claims. However, most Irish people (except Unionists) dislike the term, for understandable reasons. Clunky replacement terms such as the "North-West European Archipelago" have been suggested, but haven't caught on. Modern use in socio-geographical contexts (e.g. in textbooks) may simply refer to the group neutrally under the compound name of its two principal landmasses Great Britain and Ireland, although this neglects those many smaller islands traditionally included in the "British Isles". Politicians when talking of matters concerning both nations generally just say these islands.

- Great Britain (a geographical term) is the largest of those islands, upon which sit the countries of England (taking up the centre down to the bottom), Wales (the pointy protrusion on the middle-left, sticking out to the west), and Scotland (taking up the top of the island). The numerous small islands scattered around its coastline – the Isle of Wight, Anglesey, the Isles of Scilly, the Hebrides, the Isles of the Clyde, the Northern Isles, etc. – are (bar the Isle of Man) all part of these three and are usually lumped in with GB for convenience. To call someone "Great British" is practically unknown. The only context in which a collective term for the three GB countries is really necessary is Northern Ireland, where Great Britons are often called "Mainlanders". Of course, the existence of a "Great" Britain suggests the existence of a "Mediocre" Britain somewhere else that it needs a superlative to be distinguished from. A misconception that the term implies 'really good' is perpetuated by slogans and titles that happily play on it, e.g. "the Great British Sausage" or The Great British Bake-Off. In fact, the "Great" in this instance just means 'large' or 'main', to distinguish the island from that nearby geographic area once known as Little,[2] Lesser or Less Britain. This lesser Britain is now the northwest corner of France, the region of Brittany (Bretagne, as opposed to Grand-Bretagne): formerly semi-independent, often fought over throughout history. The ancient language of Brittany, Breton – now largely replaced by French – is Celtic, closely related to Cornish, and more distantly to Welsh, and is therefore "British" in a linguistic sense.

- Ireland (a geographical term) is another island, comprising the Republic of Ireland (which is also often called Ireland, the correct short form) and Northern Ireland, part of the UK.

- Northern Ireland (a political term) takes up, as the name implies, (part of) the northeast of Ireland. It is often referred to as Ulster, though this can be politically sensitive as not all of the old Irish province of that name is actually inside Northern Ireland – e.g. Donegal, the northernmost county in Ireland, as well as Cavan and Monaghan are part of traditional Ulster and have an Ulster (but not British or Protestant) identity but are in the Republic of Ireland. The people of Northern Ireland are divided about 60/40 between Unionists, mainly Protestant, who feel they are Brits, and Nationalists (Republicans), mainly Catholic, who feel they are Irish, and currently the ruling coalition incorporates the less extreme parts of both sides. Note that in the Republic and in Northern Ireland the terms Unionist, Loyalist, Nationalist, and Republican are all distinct and loaded. Unionists want to remain a part of the United Kingdom. Loyalists are militantly committed to that belief. Nationalists want to be unified with the rest of the island as a free republic. Republicans are militantly committed to that belief. Loyalists are Unionists and Republicans are Nationalists, but not all Unionists are Loyalists and not all Nationalists are Republicans. Anyone born in NI can choose to have British, Irish, or dual citizenship since the Good Friday Agreement to stop killing each other.[3]

- The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (a political term, one of the longest nation titles in the world but known as the "United Kingdom" for short or "UK" for shortest) comprises the island of Great Britain and associated islands, and Northern Ireland. It has 60 million people within four different constituent countries (though only England and Scotland are invariably referred to as 'countries'; Wales is still sometimes described as a 'principality' and Northern Ireland a 'province'), and is a nation state and a fairly major player in world affairs. The UK was created in 1707, as "The United Kingdom of Great Britain", after the Act of Union between England and Scotland. It was changed to "The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland", upon the Union with Ireland in 1801. The change to "The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland" came following the treaty creating the Irish Free State in 1922; the latter now known as the Republic of Ireland (see below).

- "Britain" (a geographic or political term, depending) has two meanings; (i) colloquially, as an abbreviation for Great Britain, and (ii) more formally though confusingly, as a catch-all abbreviation for the United Kingdom. "British" does officially denote someone from any part of the UK, although some may object to being so-called – thus, a Northern Irish person is legally British (politics aside), even though not from Great Britain. This is because there is no precise single word to describe "a citizen of the United Kingdom", so "British" is the most convenient shorthand; a more accurate term would be "UK-er" or "Kingdomite", say, but there is no such term in practice.[4] Wait, there is more(!): "British" in history for about the first millennium AD means "Celtic", and is contrasted with "English". That is, the early Celtic inhabitants of the islands are also known as "Brythonic", the root of the word British, and they were partly displaced by invading Germanic peoples such as the Angles (hence Angle-land: England) and Saxons. Thus, Welsh nationalists, who object to use of the word "British", are British in that sense, whereas England is not. "British" in the modern sense was basically invented when King James VI of Scotland became also James I of England.

- The British Islands, a rarely used legal term, refers to the UK, the Isle of Man, and the Channel Isles, the last of which are not part of the geographic British Isles.

- The Republic of Ireland (a political term) takes up the majority of the island of Ireland and is a separate country from Northern Ireland. It is no longer part of the UK, which has caused what might charitably be called "a spot of bother" or two in the past. "Ireland", confusing though this is, is the correct official name of the country, though 'Republic of Ireland' (with a capital R, abbreviated ROI) is frequently used to differentiate the state from the island. Another common, though faintly patronising, way to get round this is to use the Irish word for Ireland, "Éire", when referring to the country.

In short, to summarise the most common error: If something is English, it is British; but the reverse is not always true: if something is British, it is not necessarily English. So, if you refer to someone from England as being "British", you are correct - but don't make the mistake of thinking everything about the English is therefore representative of the British as a whole (see You Fail Logic Forever).

English people usually don't really care whether they're called English or British. However, "British" is arguably used much less than it used to be, and people now tend to call themselves "English", or, if being pedantic, "UK citizens". Some left-leaning/liberal people dislike "British" because of the imperial connotations - "British Empire", "British Army", etc., in comparison with the nicer connotations of "English" ("country lane", "pub", etc.). English nationalists, on the other hand, who tend to be (but are not always) right-wing, also object to it, especially now that Scotland seems to be heading for independence. "Brit" can seem slightly derogatory, but "British" is usually OK.

Some people from Cornwall, the south-west tip of England, with its own distinct Celtic heritage, do not identify as "English", preferring "Cornish". Tread carefully.

If you refer to a Scot or a Welshman as "British", the vast majority will just accept this is true as regards now, although the more nationalist may insist on a local term. Whatever happens, "British" is right, and "English" is not. Apart from being separated by borders, this is (as noted above) because the Scottish Highlanders and Welsh can trace their lineage back to the lands before the 'English' came.[5] Native Welsh and Scottish Highlanders, plus the Irish, Manx (of the Isle of Man) and Cornish, are descended from the Celts who inhabited the isles since before the Romans, whereas the 'native' English descend mainly from the successive Germanic (Angle, Saxon, Jutish, Frisian, Danish and Norwegian), and Norman (read: stinkin' French) conquests, and can be, and sometimes are, still viewed as "outsiders" and "invaders" by more radical nationalists in Wales or Scotland, hence Sassenach, Gaelic for "Saxon" and a derogatory Scottish word for English person.[6] Lowland Scottish culture is also mainly of Germanic origin (south-east Scotland has been Germanic as long as England has), and the dialect, Scots, is related to English, unlike Gaelic, which used to be the Highland language, and is still spoken in a few areas. Also, the far north of Scotland (Orkney, Shetland and part of Caithness) has a more Scandinavian heritage, but its language, Norn, died out in the 19th century (some Orcadians and Shetlanders insist they are not Scottish). Of course, time and interbreeding have long eroded the 'pure-born' of these races, and focusing on descent is a quick way to commit political suicide and get branded a racist in modern politics, even among nationalists.

If you refer to a Republican-minded Northern Irish person as "British", you may get chewed out. If you fail to refer to a Unionist-minded Northern Irish person as "British", you may get chewed out. "Ulster" is a loaded term, being mainly used by Unionists, and giving the appearance of historic legitimacy to the province, which is rejected by Republicans, especially as it makes up only 2/3 of historic Ulster. "Ulsterman" may thus be taken as offensive by NI Republicans, or by citizens of the Republic (although, in truth, a lot of people in the Republc are less bothered by this sort of thing). "Northern Irish" is pretty neutral, although some Republicans will not use it, and insist on "the occupied six counties" or some similar formulation. Exercise maximal caution, generally.

If you refer to someone from The Republic of Ireland as British, you are going to die. The same thing as pulling out a gun when surrounded by armed police, basically. Don't. Just don't. Using "English" is basically the same.

Under no circumstances should the UK as a whole be referred to as "England", which hasn't been an independent country since 1707. It is wrong. Don't do it. Don't. This is a message many would like to get across to other nations, some of whose name for the UK in their own languages is exactly the word for England. Whether you're an overseas tourist or a politician or a movie star, don't talk about the "English" response or the reception you receive in "England" when you mean the UK. If you're a pop star, don't come on stage in Edinburgh or Cardiff and scream "Hello, England!" (and for the love of all that is holy don't shout "Hello, London!") - there is no quicker or more brutal way to lose an audience. If you're a comedian, you might just get away with it. (Yell "#*@% the English!", on the other hand, and they'll probably carry you off shoulder high...)

Seriously, though. If you get this wrong, you will be forgiven. It's an easy mistake to make. There is a reason for it. England does cover over half of the UK's total land area, and does contain the vast majority (around 51 million out of 61m, currently) of its population. Even Brits get mixed up often enough - after all, even the title of this article is wrong: "Britain" and "the UK" technically refer to the same thing; it should read Great Britain Versus The UK - and until More Recently Than They Think it was accepted practice (at least by the English) for "England" and "Britain" to be interchangeable terms.

Just watch out for the Scots. They long have a reputation as being 'the hard lot from up north.' Some of them are nationalists and will not tolerate one step out of line, saying it arises from the Union, which is the root of all evil. Some are unionists... who will not tolerate a step out of line, because it undermines the Union and drives people into the arms of the Nats. Some of them, we shan't name any names, have a reaction resembling an enraged Dalek. DO-NOT-BLAS-PHEME!

Even using the terms "British" or "Scottish" isn't always enough, even though they're both correct. You've got to use the right term in context. Many Scots, Nats or otherwise, can get really infuriated with English sports commentators, who will refer to an athlete as "bringing the gold home for Britain!" yet conversely to the same athlete as "the plucky Scot, coming in fifth...". Received wisdom says that the predominantly London-based media will often hail any Scot's - or Welsh or Northern Irish person's - sporting success as "British", but (possibly unconsciously) shunt the same person off into the ghetto marked 'Scottish', 'Welsh' etc. should they trail in last. This subtrope is personified by tennis player Andy Murray: the joke goes that he is invariably referred to as British when he wins and Scottish when he loses. (The converse happens as well: English when they win, British when they lose.)

More generally the national sporting team situation is complicated. In international cricket, football, and rugby, England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland play as separate teams (the situation in rugby union is even messier, where a unified Irish national team features players from both Northern Ireland and the Republic, and in addition to the English, Scots, Welsh and Irish teams that play in tournaments a unified British Lions team tours other countries and plays their individual local teams). In athletics, tennis and the Olympic Games there is a unified British team. This causes particular problems for football at the Olympic Games, where the British team has traditionally not entered the football tournament for fear that fielding a unified British team would lead to the individual nations losing their right to separate teams in higher-profile football tournaments. The fear is so bad that the Scottish, Welsh and Irish actually allowed the English FA to enter an all-English football team in the 2012 Olympics as part of "Team GB".

With devolution (the transferring of certain legislative powers to local governing bodies, primarily a Scottish Parliament and a Welsh Assembly) and increasing Scottish and Welsh nationalism, the English too are getting more and more picky about these things. Many English people get annoyed when people from the UK are either "Scottish" (and occasionally, if they're lucky, "Welsh" or "Northern Irish") or "British" , but rarely "English" – at least, not in any positive context. The frustration is that the English are often only separated out when it comes to criticism - for example, Americans may talk about getting independence from "the English" as if the Scots and Welsh had nothing to do with it. There are also more and more English who dislike the use of the Union Flag or "God Save the Queen" in relation to purely English matters, for example English sports teams. Let's not even get started on the "West Lothian question": the idea that a Scottish or Welsh member (MP) of the UK Parliament in London can still vote on policies that, since devolution, purely concern England and not their home region when responsibility for the policy area (e.g. health, education) is devolved there to a regional legislative body. That is, the MP's decisions can affect the electorate in English MPs' constituencies - though the reverse is not possible - yet not their own constituents, if such policy is separately governed locally by the Scottish Parliament or Welsh Assembly.

Hold on, there's more... The auspices of the United Kingdom extend beyond just Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The UK also has fourteen British Overseas Territories scattered across the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, the Atlantic (e.g. The Falkland Islands) and good old Gibraltar, which are under its sovereignty, but not as part of the United Kingdom itself. Americans can consider them much like Guam or Puerto Rico are to the USA, although, naturally, there are differences.

Closer to home, there are the three Crown Dependencies too: the Bailiwick of Jersey and the Bailiwick of Guernsey (which between them cover the Channel Islands) and the Isle of Man. These are all possessions of the Crown, i.e. subject to the British monarchy, which must give final assent to their laws - but are not within the United Kingdom politically; each has its own Chief Minister and body for internal legislation, although all are treated as part of the UK for British nationality law purposes and are dependent upon it for international representation, defence etc. The Isle of Man is part of the geographic British Isles, though, lying in the middle of the northern Irish Sea between Great Britain and Ireland – and a generic application of "Britain" will usually take in the Channel Islands as well, although the latter lie some way off on the far side of the English Channel, just off the northern French coast. The actual legal status of these three micro-states is insanely complicated.

- Some idea of the complexity - the island of Sark, a semi-autonomous part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, is the last remaining feudal state in Europe, although it is now introducing democracy. The island has a population of roughly 600.

- And the Isle of Man has the world's oldest continuous parliament, and is not a member of the European Union, and is popularly thought to have no road speed limits, and the British Government has no authority there, but the Queen does, and it has its own version of the pound not interchangeable with the British one... having said that, Manx coins will occasionally find their way into the UK proper and be accepted without comment as they look almost identical.

- The Isle of Man does actually have speed limits. It has lots of them. The difference is that where there is the sign that in Great Britain means 'national speed limit' (i.e. 60 mph limit or 70 mph if there are multiple lanes) on the Isle of Man it means unlimited. That is the only time there is no speed limit. However, the police can and will pull you over for driving like an idiot regardless of the speed limit.

See also Scotireland and The Irish Question.

- ↑ Stretching the remit somewhat, out into the north Atlantic, arguably incorporates the Faroe Isles (part of Denmark) too – but let's not make things any more complicated than they're about to get already.

- ↑ not to be confused with Little Britain

- ↑ Northern Irish athletes with dual citizenship can elect to represent either the UK or the Republic of Ireland at the Olympic Games, for example. Demonstrating the density of this naming confusion, the UK team competes under the name Great Britain and Northern Ireland, but its International Olympic Committee country code is just GBR, and it is routinely referred to as "Team GB". In the sport of rugby union, the issues are cut admirably straight through: a single unified Ireland team represents the whole island.

- ↑ This unsatisfactory linguistic situation mirrors the way the Americas cover much more than just one country, yet "American" is generally used for people/things from the USA in the absence of a more literal term like "USA-er".

- ↑ This can be a controversial view: Oppenheimer argues that Germanic people have also been here since pre-Roman times.)

- ↑ It cuts both ways – the ancient Brythonic word from which Cymru, the Welsh for "Wales", derived, meant 'friend'; the English term Wales, though, derived from a word meaning 'enemy'!