Story to Gameplay Ratio

Just about every game released nowadays has at least a little story in it. Some games are almost nothing but story, such as Visual Novels—like Phoenix Wright or Hotel Dusk: Room 215.

Does this work? It depends. Games with great gameplay and no story, such as the Super Smash Bros. series, sell fantastically. Games with bad gameplay and no story tend not to last. Games with bad gameplay but a high Story to Gameplay Ratio, especially if the story is considered great, sell to those who are willing to slog through the boring game to get at the crunchy story bits and Cutscenes. Enough of those people exist to make many of these games profitable, though with the exception of a few popular ones, most of these never go anywhere near a bestsellers chart.

Many modern Role-Playing Games have a high ratio. People who hate RPGs criticize them by saying they lack gameplay.

Periods where a game takes control away from the player for the purposes of advancing the plot or tutorials are known as Exposition Breaks.

Compare Check Point Starvation.

Please note: This list is ranked. That means the closer is an item to the top, the more gameplay it has; the closer to the bottom, the more story it has. So, if you know about a really, really plot-heavy game don't place it under "Lowest Story to Gameplay Ratio"; instead, place it right above "Highest Story to Gameplay Ratio".

Lowest Story to Gameplay Ratio

- Pong.

- Many puzzle games such as Tetris have literally no story. There is not even a Hand Wave explanation as to why differently shaped blocks are falling into Red Square; just play the game.

- There is at least one exception, in Tetris Worlds there are cute little robots and their star is about to go supernova, and you have to drop the blocks into the square to power some sort of machine that terraforms other planets in other solar systems so the robots can live on them.

- There are actually several video games that consist of a story shoehorned into Tetris. Another one is Tetris Plus for the original playstation where there was a professor "doing archeology" who had to get to the bottom of the block chamber.

- N: Even after being cleverly embellished to sound like a grand quest, the page describing the ninja's basic goal (getting gold, avoiding enemies, and reaching the exit) is quite tiny.

- Parodying this, puzzle game Sub Terra has a short story which intentionally has nothing whatsoever to do with the game.

- Eversion has this one-line description of a plot hidden away in the readme file: "Princess is kidnapped. You must save princess", but it has pretty much no impact on gameplay.

- Virtual On has an even lesser ratio than the other typical fighting games. Whatever the Excuse Plot might say, the sole purpose of the game is to entertain the Gundam-maniacs; the mechas, save for Fei-Yen, do not even have a personal story of their own.

- John Carmack of Id Software maintains that story is completely incidental to gaming. The original two Dooms and the first Quake embody this philosophy, with stories no more complex than "you're here, bad guys are over there; kill them." Quake 2 is only a little bit more complex, and Quake 3 eliminates even the slightest hint of a story. Doom 3, however, is considerably more plot driven (for better or for worse), as is Raven's Quake 4.

- Roguelike genre is characterized by fairly thin plots. Nethack, Dungeon Crawl, Angband and most of its variants as well as the genre-defining Rogue feature plots no more complex than "retrieve MacGuffin" or "slay the Big Bad". Some Roguelikes have more plot - for example Ancient Domains of Mystery has a neat backstory and a more defined fantasy world than most Roguelikes, but remains ultimately driven by gameplay, not plot. Of course, for a genre that typically features Perma Death, having lots of plot to replay each time could get a bit annoying.

- Fighting games in general do have a story, but you wouldn't know it from the actual games. Most of it is All There in the Manual.

- The Touhou fighting games belong with the rest of the franchise below; in one-player Story Mode there's the same amount of in-game dialogue, with the same degree of (loose) relevance to the plot.

- The Flash fighting game Death Vegas is on the other end of the scale. Not only are there extensive cutscenes setting up each fight and placing it, but every single character's fights, and their outcomes, are a canonical part of the overarching story.

- Strange to think of it, but long-running console RPGs like Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy used to belong on this end of the scale. You had some exposition from a quest-giver to tell you what your newest goal is, some NPCs to hand out clues and advice, and the other 99% of the game was you exploring the world and thrashing monsters. The "story" was just a series of obstacles and objectives that ensured you gradually progressed from the easy areas to the hard ones. Etrian Odyssey is a modern throwback to this style of game.

- This was pointed out by Brickroad in his brilliant Let's Play of Final Fantasy I:

The SHIP storyline is also a really good indication of how RPGs used to be versus how they are now. Playing the game blindly, there's nothing to indicate that the player needs a SHIP, and nothing that points to getting one in this town. If this scenario popped up nowadays the heroes would have a long unskippable discussion about how they desperately need a ship, run a few fetch quests in town before overhearing someone talking about the PIRATEs, then come up with an elaborate scheme (probably involving a stealth minigame) to sneak aboard and take control of it somehow. Personally I prefered the old way: roll into town, beat up some chumps, sail away laughing. Also note: now that I have the SHIP I'm still not told what to do with it. It's "You have a SHIP now! Yay! Explore!" and not "You have your SHIP, now you can sail to the place you knew you needed to go!" Just feels like more of an adventure, you know?

- Final Fantasy VII spin-off Dirge of Cerberus is one long cutscene with occasional Third-Person Shooter elements.

- Final Fantasy X thus far has the highest ratio of its series; the hero goes along a linear path from one scene to the next, with occasional boss fights in between. It's only when you're ready to face the Big Bad that you finally have the freedom to travel about at your leisure, which, like Xenogears below, is pretty much for sidequests, bonus bosses, and extra scenes.

- Also, when Final Fantasy XII was released, they cut down the cutscenes; and the fans didn't like it one bit.

- Like the Final Fantasy series, Ultima and its prequel Akalabeth' began on this end of the spectrum. As both gameplay and story depth evolved, later Ultimas shifted toward the middle.

- Basically, any video game that tries to be nothing more than a game (not that that's a bad thing). There may be an intro, and an ending, with dialog, and maybe some brief cutscenes inbetween.

- Super Mario 64 is a perfect example of this. A voiced intro, a voiced ending, and nothing else except the occasional snippet of dialog from an NPC.

- Nintendo in generally makes many games of that kind even today. If there is any real depth to the story, chances are that those parts are completely optional, like the Metroid Prime scans.

- Wario Land The Shake Dimension has this, to probably the most minimal point ever. You've got an intro scene, an ending movie... and after watching them just once, you never get forced to see them again (going straight in an optional bonus menu). Same for the credits.

- Though the sequels have more developed plots, Turok Dinosaur Hunter is one of the most extreme example of this side of the scale. Apart from a short hint that appear when you load or start a new game, and a dialogue-less ending, it has no discernable plot whatsoever.

- Cult Classic Another World contains no dialogue (with the exception of an introductory sequence in the SNES version) and no cutscenes; however, the game is rich with narrative, all expressed through its (linear) gameplay and setpieces. Its minimalism influenced many future games.

- Bangai-O Spirits does not even pretend to have a plot in contrast to its predecessor which at least had an Excuse Plot. The little character interaction that there is tends to include discussions of this issue.

- The first two Merlin's Revenge games had a moderately long cutscene at the beginning and end of each game, with the story having no impact on gameplay. This was changed a bit with the third game, which added a few very short, skippable cutscenes in the middle of the game, most notably the scene with the stone inscription.

- The Japanese Dreamcast version of Ikaruga is basically five stages of outright blasting and combo action with a few lines of story at the start of each stage. The most story-heavy section of the game is the last stage, where there are a few lines preceding each of the boss's four phases, and there's some "dialogue" right at the very end... And that's about it. Control is taken away from the player twice per stage; Once at the end of the intro section, again when the boss appears, (except in the last stage, since the boss appears immediately after the intro section) and at the "stage clear" screen. Any other time, the player is free to move and shoot however they like.

- In the English Gamecube port, even this little amount of story is ripped away; The only story to be had is in the manual, and in the very final cutscene.

- The Touhou Project series features dialogue just before each boss fight...and that's about it, unless you have the Japanese manual. And much of that dialogue doesn't have anything to do with the main plot until the last 2 or 3 stages. This gives its vibrant fanbase plenty of room to come up with all sorts of fanon.

- Meteos has an opening cutscene and an ending based on which mode you play, and nothing else. This doesn't stop what little amount of story that shows up there from being amusing. It also has brief descriptions of each world, typical of games that like to have a bit of story without getting in the way of the action.

- The Star FOX series typically has a 1-2 minute long cutscene at the beginning and end of each stage. Most of the plot comes from in-game transmissions that take place during gameplay.

- Borderlands. It had a plot way back in preproduction, but it disappeared right about the time the dev team decided to cel shade everything to hide graphical flaws. The game is ten hours of chest farming and collecting macguffins to get to the next zone, framed by an Excuse Plot.

- Team Fortress 2 has literally no story. The "Meet the [Class]" movies give the characters some additional dimensions, and it's implied in a couple of places that RED (Reliable Excavation Demolition) is a demolition company and BLU (Builders League United) is a construction company, but that's about it.

- This page adds a bit more background to the teams, but essentially the story boils down to "two companies that control the world have hired mercenaries to kill each other. Go help them".

- Now, it has much more story with this comic and this page, the latter which describes how the whole mess started.

- The plot still pretty much remains in the background, however, and when a plot point actually does appear in-game, it usually just takes the form of a taunt or response line.

- Left 4 Dead. There are small cutscenes at the beginning of each campaign that last under a minute. There is dialogue throughout the levels, but they take place during the actual gameplay. Not to mention there is writing on the walls which is optional for the players to look at.

- Nothing Is Scarier in effect. With this game and it's sequel, much of the cause and backstory of the ensuing Zombie Apocalypse are only in the footnotes. The characters only meet at the start of the game(or at least a week earlier in the case of the first game), meaning that not all of them are exactly open to sharing their personalities and getting attached, as you never know who's going to turn next.

- Gears of War had quite a few cutscenes, but they were never very long, and there wasn't much story behind them. The sequel had a more in-depth storyline, but the cutscenes were still not very long, with most of the plot being told in in-game transmissions.

- Portal tells most of the story through the passive-aggressive ravings of an AI and the implications of the environment. Most of the game is about performing physics-warping puzzles and getting from place to place - and yet the game's writing was one of its biggest selling points, being pitch-dark and very, very funny.

- One must note, however, that it has been hinted at that Portal takes place in the same universe as the Half-Life series; if that's the case (and the connections are revealed in later games), it could have an impressive amount of backstory from the relatively important information about that series.

- Portal 2, while keeping the physics-warping puzzles from the first game, expands beyond the test chambers and has quite a bit more story, mostly through the dialogue of the A Is and recorded messages you hear throughout.

- The early, 8-bit Ninja Gaiden games (not to be confused with the current ones). The original Ninja Gaiden was one of the very first games to have many well-done cutscenes with a genuinely interesting story filled with twists and turns. The fact that it was backed up by some great (if impossible) gameplay helped a lot as well. One of the first games which caused players to beat each level to see what happens next in the story.

- Incidentally, the writer for these games would later go on to work on a number of beloved Square Soft RPGs, specifically the Chrono series and Xenogears. He did not, however, return for...

- The 3D Ninja Gaiden games, which seem to have taken the opposite approach to their predecessors; the story is incomprehensible, uninspired and entirely uninteresting, but strictly relegated to cutscenes that are short, flashy and far-between. The main incentive for the players to keep going is simply to challenge themselves. It works for what it is, but it's ironic and somewhat sad that the reboot of a series that helped pioneer the concept of story in action games would completely abandon such a defining feature of its predecessors.

- Myst and most of its sequels/imitators. There is a story, but it definitely takes a back seat to wandering around beautiful, lonely worlds solving fiendish puzzles. (Individual sequels waver a bit - Myst gives you almost nothing to start with, and each subsequent game adds a little more story and a little less puzzles.)

- The split between Myst and its sequels is because of the story. In Myst, all of the story is backstory and you only really learn it at the very end. The only storyline in the game itself is "go fetch" and there's only one decision in the game that's story driven, so the puzzles and the pretty pictures are all gameplay. In all of the sequels, you're an active part of the ongoing story and the puzzles are part of (or drive) the storyline, so they belong much farther down this list.

- Vietcong. The briefing and debriefing cutscenes are rather long, but the rest of the game is mostly a standard jungle FPS.

- No More Heroes has several-minute-long cutscenes before and after boss fights, but most of the game is spent doing odd assassination jobs around the city, exploring the city, fighting through the levels, etc.

- Its creator's previous game, on the other hand, was notorious for having well-directed, stylish cutscenes (and a lot of them) and an extremely complex and ambitious story... juxtaposed with highly linear and questionably interesting gameplay.

- And by contrast, his most recent game has (mostly) shorter cutscenes and more gameplay than ever, which has earned it greater praise from critics but mixed responses from fans.

- Half-Life has a low to moderate ratio: there is story and dialog, yes, but you never lose control of Gordon Freeman during any dialog or event. On the other hand, because you often can't move Gordon to the next area until the dialog is completed (which is usually when the person talking unlocks the door or whatever is in your way), these scenes can arguably be thought of as semi-interactive unskippable cutscenes.

- The Silent Hill series. The cutscenes don't go on for too long, and are spaced out reasonably. Yet a lot of story is contained within those scenes.

- Dwarf Fortress is an odd, hard-to-place example. The world you play on has an extremely rich and detailed backstory that's completely procedurally-generated, but in Fortress Mode they're largely irrelevant, unless you find yourself with a situation where you're the last surviving settlement of a Vestigal Empire that everyone else is at war with.

- The Panzer Dragoon series is a shooter series with a vast amount of backstory, but most of it is optional, aside from 2-minute cutscenes at the beginning of each stage.

- Halo sits much higher on the list than one would expect with its rather frenetic violence and combat. This is mostly because in addition to a lot of cutscenes, the games makes a point of having plenty of exposition and dialogue taking place during the levels.

- Marathon, Bungie's other FPS series is also high on the list due to story and worldbuilding delivered through the terminals, during the time when the plot of FPS games amounted to "kill monsters". The series's story writer Greg Kirkpatrick, responded to complaints about Marathon's "confusing and unnecessary story" with an answer that is an opposite of John Carmack's own view on this near the top of this list: Read my lips: Computer games tells stories. That's what they're for.

- Mass Effect sits a bit lower down than some would expect, as a lot of its dialogue is skippable. However, it is quite hefty on the talking side of things, but still has plenty of action.

- Well, not to mention that the dialogue is playable, so it's really not not gameplay.

- Hell, pick a BioWare game. Any BioWare game. For good or ill, they put a lot of their efforts on characters. For every half-hour spent on dungeon-crawls and slaying monsters, expect an hour and a half of helping your colorful crew through their CharacterArcs.

- Uncharted is quite high on story, AND gameplay. This is part of its appeal.

- The Trauma Center series has long dialog scenes before and after operations, but after you've beaten the operation once, you can skip right past them.

- Mother 3 has a great story especially when you get to thinking about it. Its gameplay is still challenging and/or enjoyable, but the story is the reason why half of its pages even exist. It's the darkest of the MOTHER series but still keeps the quirky charm of its predecessors, if that's even possible.

- There are two types of Fire Emblem players: the type that only see the support system in terms of the bonuses it gives to combat, and the type that launches The Support Conversation Project.

- Due to Gameplay Roulette, the ratio of Rance games varies, but it's usually quite even. On one hand, there are a good number of cut scenes. On the other hand, they are Visual Novel style cutscenes and can be quickly read through. There's also the fact that the games involve a significant amount of Grinding to get through due to their Nintendo Hard nature.

Even Story-to-Gameplay Ratio

- Zone of the Enders: The Second Runner, while not as exposition-heavy as Hideo Kojima's other franchise, frequently splits up the action with scenes upwards of ten minutes long, but the game also has some versus mode with no story. In fact, this is roughly the middlepoint of the scale, being completely balanced between story and gameplay.

- Kingdom Hearts II deserves a mention here. Entering a new room? Cutscene! Wait, it's just a corridor. Regain control of your character long enough to walk down it for three seconds. Next room: Cutscene! Goofy says something, monsters appear, regain control to fight them, battle ends, Cutscene! "That sure was a tough battle, Sora..." and so on. To be fair, you can skip all of these cutscenes and get straight to the gameplay; that doesn't change the fact that there are so many of them, though.

- It's prequel Birth By Sleep has a similar problem.

- Dating Sims are rather similar to Visual Novels as far as gameplay goes, differing in that they you a greater variety of choices and actually allow your mistakes to play out instead of slapping you with a bad ending immediately.

- BlazBlue has a very large, very complex plot, especially for a fighting game. A character's story usually consists of about six or seven short matches and up to an hour of text.

- The Ace Attorney series is essentially a story that you help move forward by doing the right pre-determined things. It's slightly more interactive than a traditional Visual Novel, but not much more.

- Meta example: classic 1982 ZX Spectrum text adventure The Hobbit. Gameplay was heavily reliant on the story for direction and atmosphere, it's just that said story had been published 45 years previously.

- World of Warcraft is a little odd in this regard. There's lots of story in terms of dialog from NPCs and other characters, but all of it can be (and often is by most players) ignored by those who just want to jump into the quests.

- The Warcraft universe have a really good story-lines but it is safe to say that the game's immense popularity is not because of its story. The game would likely still be as popular as it is even if it had virtually no story.

- Quite a lot of modern Interactive Fiction puts the emphasis on "fiction" to the point where puzzles (the most gamelike elements of the genre) are completely dispensed with in favor of narrative exploration. Photopia is the preeminent example.

- Dreamfall; the first and last few chapters in particular consist almost exclusively of steering your character around from one cutscene to another.

- Hellsinker is notable for being incredibly plotheavy for a Shmup.

- Final Fantasy XIII sets a new bar for the series: it's been called an interactive 50-hour film, somewhere.

- Seeing as Final Fantasy X faced the same criticisms back in the day, that means that Final Fantasy XIII has actually surpassed Final Fantasy X in this area!

- Asura's Wrath: It's far from boring however, being basically an interactive action Anime.

- Planescape: Torment isn't so much an actual game so much as it is a highly interactive novel.

- The Xenosaga series, which is essentially several movies with occasional interactive parts.

- Just to show how bad it was in the first game, in the first few hours, playtime was only about a fifth of the cutscene time. And the scene when you first get on to the ship you're going to be going around in for the rest of the game, is thirty minutes long, and they even let you save mid-scene.

- The second game was slightly better, but not by much.

- Xenogears is similar, being essentially a part of the same series. Not only does the game interface come off as somewhat hastily assembled (and it probably was), but the game's story is extremely involved. Disc 2, which the dev team didn't even have time to finish, is essentially one huge cutscene interrupted by a couple dungeons. You finally get access to the world map just before the final dungeon, for the sake of sidequests.

- And in an insane twist of irony, Xeno-creator Tetsuya Takahashi has specifically described his next game, Xenoblade (no relation to previous Xeno-titles) as being on the exact opposite end of the scale from his (in)famous previous works, calling the pursuit of excessive story-to-gameplay ratio "a dead end". That he is now working with Nintendo (see above) may or may not have anything to do with this new direction. Or maybe he just played...

- Just to show how bad it was in the first game, in the first few hours, playtime was only about a fifth of the cutscene time. And the scene when you first get on to the ship you're going to be going around in for the rest of the game, is thirty minutes long, and they even let you save mid-scene.

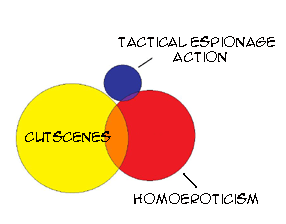

- Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots, a game which deserves a special place, due to the sheer length and quantity of its cutscenes being substantially greater than the previous games in the series. Cutscene-wise it's less like one game and more like five full-length movies.

- Most estimates put the total run time of Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriotss cutscenes at around nine hours. To compare to another AAA blockbuster title, Halo 3s total cutscene running time is ... 44 minutes.

- The ending cutscene alone is so long, there is actually a save point in the middle of it.

- The Metal Gear Solid series in general has been called "the best [or worst] movie I ever played" by some who criticized its sheer number of dialog scenes, which occasionally last longer than the actual gameplay. This plays into a long-running joke that there will never be a Metal Gear movie. There's no point. There already is one - the game itself.

- Honourable mention should go to Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, whose limited edition version included a bonus disc with all of the cutscenes edited together into a feature film version of the game, thus saving gamers the hassle of having to play anything at all!

- While it is a different franchise, Metroid: Other M did the movie thing as well.

- Most estimates put the total run time of Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriotss cutscenes at around nine hours. To compare to another AAA blockbuster title, Halo 3s total cutscene running time is ... 44 minutes.

- Dragon's Lair is basically a movie where the player has to press certain buttons at certain times or die.

- [Fahrenheit, also known as Indigo Prophecy in the USA, has been defined as an "interactive movie" by its creators. Its gameplay and story very much overlap and complement each other.

- Likewise with Heavy Rain, the new game by the same developers.

- Despite being almost entirely focused on its plot, the story is surprisingly flexible and control is only very rarely taken away from the player due to the almost entirely contextual control scheme.

- Like Visual Novels, the classic Sierra On-Line/ LucasArts-style Adventure Game genre in general can be very linear, with simpler games like Loom amounting to little more than a series of cutscenes separated by inventory puzzles.

- The Steam release of Dear Esther is, in essence, a two hour film that you can examine and traverse at your own pace.[1] There aren't even any puzzles or challenges, just a narrating voice and subtle cues guiding the player through plot, Scenery Porn and a great soundtrack.

- Visual Novels. Someone defined the genre as "That kind of Japanese game where you pick a choice and then pray that you didn't screw it up".

- Kinetic Novels, such as Planetarian and Higurashi no Naku Koro ni, don't even give you any choices, and their "gameplay" is essentially pressing a button to read more.

Highest Story to Gameplay Ratio

- ↑ if you took away the WASD and Mouse controls, it would be a movie from a first person perspective