WeChat (Chinese: 微信; pinyin: Wēixìn (![]()

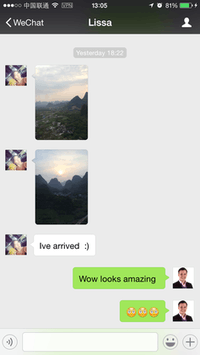

WeChat Running on Apple iOS 8 | |||

| Developer(s) | Tencent Holdings Limited | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial release | 21 January 2011 (as Weixin) | ||

| Preview release(s) | |||

| |||

| Operating system | Android, iOS, macOS, Windows | ||

| Available in | 17 languages | ||

List of languages Arabic, English, French, German, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Malay, Portuguese, Russian, Simplified Chinese, Spanish, Thai, Traditional Chinese, Turkish, Vietnamese | |||

| Type | Instant messaging client | ||

| License | Proprietary freeware | ||

| Website | www weixin | ||

User activity on WeChat is analyzed, tracked and shared with Chinese authorities upon request as part of the mass surveillance network in China.[8][9][10][11][12] WeChat censors politically sensitive topics in China.[13][14][15][16] Data transmitted by accounts registered outside of China is surveilled, analyzed and used to build up censorship algorithms in China.[17][12] In response to a border dispute between India and China, WeChat was banned in India in June 2020.[18] On August 6, 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order banning U.S. "transactions" with WeChat in 45 days.[19]

History

WeChat began as a project at Tencent Guangzhou Research and Project center in October 2010.[20] The original version of the app was created by Allen Zhang and named "Weixin" by Ma Huateng, CEO of Tencent[21] and launched in 2011. The government has actively supported the development of the e-commerce market in China—for example in the 12th five-year plan (2011–2015).[22]

By 2012, when the number of users reached 100 million, Weixin was re-branded "WeChat" for the international market.[23]

WeChat had over 889 million monthly active users in 2016. As of 2019, WeChat's monthly active users have increased to an estimate of one billion. After the launch of WeChat payment in 2013, its users reached 400 million the next year,[24][25][26] 90 percent of whom were in China.[27] By comparison, Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp (two other competitive international messaging services better known in the West) had about one billion monthly active users in 2016 but did not offer most of the other services available on WeChat.[3][28] For example, in Q2 2017, WeChat's revenues from social media advertising were about US$0.9 billion (RMB6 billion) compared to Facebook's total revenues of US$9.3 billion, 98% of which were from social media advertising. WeChat's revenues from its value-added services were US$5.5 billion.[29]

According to SimilarWeb, WeChat was the most popular messaging app in China and Bhutan in 2016.[30]

Features

Messaging

WeChat provides text messaging, hold-to-talk voice messaging, broadcast (one-to-many) messaging, video calls and conferencing, video games, photograph and video sharing, as well as location sharing.[31] WeChat also allows users to exchange contacts with people nearby via Bluetooth, as well as providing various features for contacting people at random if desired (if people are open to it). It can also integrate with other social networking services such as Facebook and Tencent QQ.[32] Photographs may also be embellished with filters and captions, and automatic translation service is available.

WeChat supports different instant messaging methods, including text message, voice message, walkie talkie, and stickers. Users can send previously saved or live pictures and videos, profiles of other users, coupons, lucky money packages, or current GPS locations with friends either individually or in a group chat. WeChat's character stickers, such as Tuzki, resemble and compete with those of LINE, a Korean messaging application.[33]

Public accounts

WeChat users can register as an public account (公众号), which enables them to push feeds to subscribers, interact with subscribers and provide them with services. There are three types of official accounts: a service account, a subscription account and an enterprise account. Once users as individuals or organizations set up a type of account, they cannot change it to another type. By the end of 2014, the number of WeChat official accounts had reached 8 million.[34] Official accounts of organizations can apply to be verified (cost 300 RMB or about US$45). Official accounts can be used as a platform for services such as hospital pre-registrations,[35] visa renewal[36] or credit card service.[37] To create an official account, the applicant must register with Chinese authorities, which discourages "foreign companies".[38]

Moments

"Moments" (朋友圈) is WeChat's brand name for its social feed of friends' updates. "Moments" is an interactive platform that allows users to post images, text, and short videos taken by users. It also allows users to share articles and music (associated with QQ Music or other web-based music services). Friends in the contact list can give thumbs up to the content and leave comments. Moments can be linked to Facebook and Twitter accounts, and can automatically post Moments content directly on these two platforms.[32]

In 2017 WeChat had a policy of a maximum of two advertisements per day per Moments user.[28]

Privacy in WeChat works by groups of friends: only the friends from the user's contact are able to view their Moments' contents and comments. The friends of the user will only be able to see the likes and comments from other users only if they are in a mutual friend group. For example, friends from high school are not able to see the comments and likes from friends from a university. When users post their moments, they can separate their friends into a few groups, and they can decide whether this Moment can be seen by particular groups of people.[39] Contents posted can be set to "Private", and then only the user can view it.

WeChat Pay digital payment services

Users who have provided bank account information may use the app to pay bills, order goods and services, transfer money to other users, and pay in stores if the stores have a WeChat payment option. Vetted third parties, known as "official accounts", offer these services by developing lightweight "apps within the app".[40] Users can link their Chinese bank accounts, as well as Visa, MasterCard and JCB.[41]

WeChat Pay (微信支付) is a digital wallet service incorporated into WeChat, which allows users to perform mobile payments and send money between contacts.[42]

Although users receive immediate notification of the transaction, the WeChat Pay system is not an instant payment instrument, because the funds transfer between counterparts is not immediate.[43] The settlement time depends on the payment method chosen by the customer.

Every WeChat user has their own WeChat Payment account. Users can acquire a balance by linking their WeChat account to their debit card, or by receiving money from other users. For non-Chinese users of WeChat Pay, an additional identity verification process of providing a photo of a valid ID as well as oneself is required before certain functions of WeChat Pay become available. Users who link their credit card can only make payments to vendors, and cannot use this to top up WeChat balance. WeChat Pay can be used for digital payments, as well as payments from participating vendors.[44] As of March 2016, WeChat Pay had over 300 million users.[45]

In 2014 for Chinese New Year, WeChat introduced a feature for distributing virtual red envelopes, modelled after the Chinese tradition of exchanging packets of money among friends and family members during holidays. The feature allows users to send money to contacts and groups as gifts. When sent to groups, the money is distributed equally, or in random shares ("Lucky Money"). The feature was launched through a promotion during China Central Television's heavily watched New Year's Gala, where viewers were instructed to shake their phones during the broadcast for a chance to win sponsored cash prizes from red envelopes. The red envelope feature significantly increased the adoption of WeChat Pay. According to the Wall Street Journal, 16 million red envelopes were sent in the first 24 hours of this new feature's launch.[46] A month after its launch, WeChat Pay's user base expanded from 30 million to 100 million users, and 20 million red envelopes were distributed during the New Year holiday. In 2016, 3.2 billion red envelopes were sent over the holiday period, and 409,000 alone were sent at midnight on Chinese New Year.[44]

In 2016, WeChat started a service charge if users transferred cash from their WeChat wallet to their debit cards. On 1 March, WeChat payment stopped collecting fees for the transfer function. Starting from the same day, fees will be charged for withdrawals. Each user had a 1,000 Yuan (about US$150) free withdrawal limit. Further withdrawals of more than 1,000 Yuan were charged a 0.1 percent fee with a minimum of 0.1 Yuan per withdrawal. Other payment functions including red envelopes and transfers were still free.[47]

WeChat Pay's main competitor in China and the market leader in online payments is Alibaba Group's Alipay. Alibaba company founder Jack Ma considered the red envelope feature to be a "Pearl Harbor moment", as it began to erode Alipay's historic dominance in the online payments industry in China, especially in peer-to-peer money transfer. The success prompted Alibaba to launch its own version of virtual red envelopes in its competing Laiwang service. Other competitors, Baidu Wallet and Sina Weibo, also launched similar features.[44]

In 2019 it was reported that WeChat had overtaken Alibaba with 800 million active WeChat mobile payment users versus 520 million for Alibaba's Alipay.[48][28] However Alibaba had a 54 per cent share of the Chinese mobile online payments market in 2017 compared to WeChat's 37 per cent share.[49] In the same year, Tencent introduced "WeChat Pay HK", a payment service for users in Hong Kong. Transactions are carried out with the Hong Kong dollar.[50] In 2019 it was reported that Chinese users can use WeChat Pay in 25 countries outside of China, including, Italy, South Africa and the UK.[48]

In the 2018 Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholders meeting, Charlie Munger identified WeChat as one of the few potential competitors to Visa, Mastercard and American Express.[51]

Enterprise WeChat

For work purposes, companies and business communication, a special version of WeChat called Enterprise WeChat (or Qiye Weixin) was launched in 2016. The app was meant to help employees separate work from private life.[52] In addition to the usual chat features, the program let companies and their employees keep track of annual leave days and expenses that need to be reimbursed, employees could ask for time off or clock in to show they were at work.[52][53][54][55]

WeChat Mini Program

In 2017, WeChat launched a feature called "Mini Programs" (小程序).[56] A mini program is an app within an app. Business owners can create mini apps in the WeChat system, implemented using JavaScript plus a proprietary API.[57] Users may install these inside the WeChat app. In January 2018, WeChat announced a record of 580,000 mini programs. With one Mini Program, consumers could scan the Quick Response code using their mobile phone at a supermarket counter and pay the bill through the user's WeChat mobile wallet.[22] WeChat Games have received huge popularity, with its "Jump Jump" game attracting 400 million players in less than 3 days and attaining 100 million daily active users in just two weeks after its launch, as of January 2018.[58][59][60]

Mini Programs also allow businesses to sell on WeChat directly to consumers, using WeChat Pay as the payment mechanism.

Other

WeChat is colloquially called as "wx" or "vx", the initials of "Weixin".[61]

In 2015, WeChat offered a heat map feature that showed crowd density. Quartz columnist Josh Horwitz alleged the feature is being used by the Chinese government to track irregular assemblies of people to determine unlawful assembly.[62]

In January 2016, Tencent launched WeChat Out, a VOIP service allowing users to call mobile phones and landlines around the world. The feature allowed purchasing credit within the app using a credit card. WeChat Out was originally only available in the United States, India, and Hong Kong, but later coverage was expanded to Thailand, Macau, Laos, and Italy.[63][64]

In March 2017, Tencent released WeChat Index. By inserting a search term in the WeChat Index page, users could check the popularity of this term in the past 7, 30, or 90 days.[65] The data was mined from data in official WeChat accounts and metrics such as social sharing, likes and reads were used in the evaluation.

In May 2017 Tencent started news feed and search functions for its WeChat app. The Financial Times reported this was a "direct challenge to Chinese search engine Baidu".[66]

WeChat allowed people to add friends by a variety of methods, including searching by username or phone number, adding from phone or email contacts, playing a "message in a bottle" game, or viewing nearby people who are also using the same service. In 2015 WeChat added a "friend radar" function.[67]

In 2017, WeChat was reported to be developing an augmented reality (AR) platform as part of its service offering. Its artificial intelligence team was working on a 3D rendering engine to create a realistic appearance of detailed objects in smartphone-based AR apps. They were also developing a simultaneous localization and mapping technology, which would help calculate the position of virtual objects relative to their environment, enabling AR interactions without the need for markers, such as Quick Response codes or special images.[68]

In Spring 2020, Wechat users are now able to change their Wechat ID more than once, being allowed to change their username only once per year.[69][70] Prior to this, a Wechat ID could not be changed more than once.

WeChat Business

WeChat Business (微商) is one of the latest mobile social network business model after e-commerce, which utilizes business relationships and friendships to maintain a customer relationship.[71] Comparing with the traditional E-business like JD.com and Alibaba, WeChat Business has a large range of influence and profits with less input and lower threshold, which attracts loads of people to join in WeChat business.[72]

Marketing modes

B2C Mode

This is the main profit mode of WeChat Business. The first one is to launch advertisements and provide service through WeChat Official Account, which is a B2C mode. This mode has been used by many hospitals, banks, fashion brands, internet companies and personal blogs because the Official Account can access to online payment, location sharing, voice messages, mini-games and so on. It is like a 'mini app', so the company has to hire specific staff to manage the account. By 2015, there are more than 100 million WeChat Official Accounts in this platform.[73]

B2B Mode

WeChat salesperson in this mode is to agent and promote products by individual, which belongs to C2C mode. In this mode, individual sellers always post relevant photos and messages of their agent products on the WeChat Moments or WeChat groups and sell products to their WeChat friends. Besides, they develop a friendship with their customers by sending messages in festivals or write comments under their updates on WeChat moments to increase their trust. Also, continuing to communicate with the regular customers raises the 'WOF'(word-of-mouth) communications, which influences decision-making. Some of the WeChat businessman already have an online shop in Taobao, but use WeChat to maintain existing customers.[74]

Existing problems

As more and more people have joined WeChat Business, it has brought many problems. For example, some sellers have begun to sell fake luxury goods such as bags, clothes and watches. Some of them have special channels to obtain high-quality fake luxury products and sell them at a low price. Moreover, some sellers have even disguised themselves as international flight attendants or overseas students to post fake stylish photos on WeChat Moments. They then claim that they can provide overseas purchasing services but sell fake luxury goods at the same price as the true one.[75] Another hot product selling on WeChat is facial masks. Its marketing mode is like that of Amway but most goods are unbranded products which came from illegal factories making excess hormones which could have serious effects on a customer's health.[76] However, it is difficult for customers to defend their rights because a large number of sellers' identities are uncertified. Additionally, the lack of any supervision mechanism in WeChat business also provides chances for criminals to continue this illegal behavior.[77][78]

Marketing

Campaigns

In a 2016 campaign, users could upload a paid photo on "Moments" and other users who could pay to see the photo and comment on it. The photos were taken down each night.[79]

Collaborations

In 2014, Burberry partnered with WeChat to create its own WeChat apps around its fall 2014 runway show, giving users live streams from the shows.[80] Another brand, Michael Kors used WeChat to give live updates from their runway show, and later to run a photo contest "Chic Together WeChat campaign".[81]

In 2016, L'Oréal China cooperated with Papi Jiang to promote their products. Over one million people watched her first video promoting L'Oreal's beauty brand MG.[82][83]

In 2016, WeChat partnered with 60 Italian companies (WeChat had an office in Milan) who were able to sell their products and services on the Chinese market without having to get a license to operate a business in China.[84] In 2017, Andrea Ghizzoni, European director of Tencent, said that 95 percent of global luxury brands used WeChat.[84]

Platforms

Currently, WeChat's mobile phone app is available only for Android and iPhone.[85] BlackBerry, Windows Phone, and Symbian phones were supported before. However, as of 22 September 2017, WeChat is no longer working on Windows Phones.[86][87] The company ceased the development of the app for Windows Phones before the end of 2017. Although Web-based OS X[88] and Windows[89] clients exist, this requires the user to have the app installed on a supported mobile phone for authentication, and neither message roaming nor 'Moments' are provided.[90] Thus, without the app on a supported phone, it is not possible to use the web-based WeChat clients on the computer.

The company also provides WeChat for Web, a web-based client with messaging and file transfer capabilities. Other functions cannot be used on it, such as the detection of nearby people, or interacting with Moments or Official Accounts. To use the Web-based client, it is necessary to first scan a QR code using the phone app. This means it is not possible to access the WeChat network if a user does not possess a suitable smartphone with the app installed.[91]

WeChat could be accessed on Windows using BlueStacks until December 2014. Beginning then, WeChat blocks Android emulators and accounts that have signed in from emulators may be frozen.[92]

There have been some reported issues with the Web client.[93] Specifically when using English, some users have experienced autocorrect, autocomplete, auto-capitalization, and auto-delete behavior as they type messages and even after the message was sent. For example, "gonna" was autocorrected to "go", the E's were auto-deleted in "need", "wechat" was auto-capitalized to "Wechat" but not "WeChat", and after the message was sent, "don't" got auto-corrected to "do not". However, the auto-corrected word(s) after the message was sent appeared on the phone app as the user had originally typed it ("don't" was seen on the phone app whereas "do not" was seen on the Web client). Users could translate a foreign language during a conversation and the words were posted on Moments.[94]

Wechat opens up video calls for multiple people not only to one person call.

Security concerns

State surveillance and intelligence gathering

WeChat operates from China under Chinese law, which includes strong censorship provisions and interception protocols.[95] WeChat can access and expose the text messages, contact books, and location histories of its users.[95] Due to WeChat's popularity, the Chinese government uses WeChat as a data source to conduct mass surveillance in China.[8][9][10][96]

States/Regions such as India,[95][97][98] Australia[99] the United States,[100] and Taiwan fear that the app poses a threat to national or regional security for various reasons.[95][101] In June 2013, the Indian Intelligence Bureau flagged WeChat for security concerns. India has debated whether or not they should ban WeChat for its possibility in collecting too much personal information and data from its users.[97][102][103] In Taiwan, legislators were concerned that the potential exposure of private communications was a threat to regional security.

In 2016, Tencent was awarded a score of zero out of 100 in an Amnesty International report ranking technology companies on the way they implement encryption to protect the human rights of their users.[104] The report placed Tencent last out of a total of 11 companies, including Facebook, Apple, and Google, for the lack of privacy protections built into WeChat and QQ. The report found that Tencent did not make use of end-to-end encryption, which is a system that allows only the communicating users to read the messages.[105] It also found that Tencent did not recognize online threats to human rights, did not disclose government requests for data, and did not publish specific data about its use of encryption.[106]

A September 2017 update to the platform's privacy policy detailed that log data collected by WeChat included search terms, profiles visited, and content that had been viewed within the app. Additionally, metadata related to the communications between WeChat users—including call times, duration, and location information—was also collected. This information, which was used by Tencent for targeted advertising and marketing purposes, might be disclosed to representatives of the Chinese government:[107][108]

- To comply with an applicable law or regulations.

- To comply with a court order, subpoena, or other legal process.

- In response to a request by a government authority, law enforcement agency, or similar body.

In May 2020, Citizen Lab published a study that claimed that WeChat monitors foreign chats to hone its censorship algorithms.[109][110][111]

Privacy issues

Users inside and outside of China also have expressed concern for the privacy issues of the app. Human rights activist Hu Jia was jailed for three years for sedition. He speculated that the officials of the Internal Security Bureau of the Ministry of Public Security listened to his voicemail messages that were directed to his friends, repeating the words displayed within the voice mail messages to Hu Jia. Chinese authorities have further accused the WeChat app of threatening individual safety. China Central Television (CCTV), a state-run broadcaster, featured a piece in which WeChat was described as an app that helped criminals due to its location-reporting features. CCTV gave an example of such accusations through reporting the murder of a single woman who, after he attempted to rob her, was murdered by a man she met on WeChat. The location-reporting feature, according to reports, was the reason for the man knowing the victim's whereabouts. Authorities within China have linked WeChat to numerous crimes. The city of Hangzhou, for example, reported over twenty crimes related to WeChat in the span of three months.[95][112]

XcodeGhost malware

In 2015, Apple published a list of the top 25 most popular apps infected with the XcodeGhost malware, confirming earlier reports that version 6.2.5 of WeChat for iOS was infected with it.[113][114][115] The malware originated in a counterfeit version of Xcode (dubbed "XcodeGhost"), Apple's software development tools, and made its way into the compiled app through a modified framework.[116] Despite Apple's review process, WeChat and other infected apps were approved and distributed through the App Store. Even though some sources claimed that the malware was capable of prompting the user for their account credentials, opening URLs and reading the device's clipboard,[117] Apple responded that the malware was not capable of doing "anything malicious" or transmitting any personally identifiable information beyond "apps and general system information" and that it had no information that suggested that this had happened.[113] Some commentators considered this to be the largest security breach in the App Store's history.[116]

Ban in India

In June 2020, the Government of India banned WeChat along with 58 other apps citing data and privacy issues.[118] Border tensions between India and China earlier in 2020 might have also played a role in the ban.[96][119] The banned Chinese apps were "stealing and surreptitiously transmitting users’ data in an unauthorized manner to servers which have locations outside India," and was "hostile to national security and defense of India", claimed India's Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology.[119]

Ban in the United States

On August 6, 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order, invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, seeking to ban WeChat in the U.S. in 45 days.[19]

Censorship

Global censorship

Starting in 2013 reports arose that Chinese-language searches even outside China were being keyword filtered and then blocked.[13][14] This occurred on incoming traffic to China from foreign countries but also exclusively between foreign parties (the service had already censored its communications within China). In the international example of blocking, a message was displayed on users' screens: "The message "南方周末" your message contains restricted words. Please check it again." These are the Chinese characters for a Guangzhou-based paper called Southern Weekly (or, alternatively, Southern Weekend). The next day Tencent released a statement addressing the issue saying "A small number of WeChat international users were not able to send certain messages due to a technical glitch this Thursday. Immediate actions have been taken to rectify it. We apologize for any inconvenience it has caused to our users. We will continue to improve the product features and technological support to provide a better user experience." WeChat planned to build two different platforms to avoid this problem in the future; one for the Chinese mainland and one for the rest of the world. The problem existed because WeChat's servers were all located in China and thus subjected to its censorship rules.[15][120][16]

Following the overwhelming victory of pro-democracy candidates in the 2019 Hong Kong local elections WeChat censored messages related to the election and disabled the accounts of posters in other countries such as U.S. and Canada.[121] Many of those targeted were of Chinese ancestry.[122]

In 2020, WeChat started censoring messages concerning the coronavirus.[123]

Two censorship systems

In 2016, the Citizen Lab published a report saying that WeChat was using different censorship policies in mainland China and other areas. They found that:[124]

- Keyword filtering was only enabled for users who registered via phone numbers from mainland China;

- Users did not get notices anymore when messages are blocked;

- Filtering was more strict on group chat;

- Keywords were not static. Some newfound censored keywords were in response to current news events;

- The Internal browser in WeChat blocked Chinese accounts from accessing some websites such as gambling, Falun Gong and critical reports on China. International users were not blocked except for accessing some gambling and pornography websites.

Restricting sharing websites in "Moments"

In 2014, WeChat announced that according to "related regulations", domains of the web pages that want to get shared in WeChat Moments need to get an Internet Content Provider (ICP) license by 31 December 2014 to avoid being restricted by WeChat.[125]

Iran

In September 2013 WeChat was blocked in Iran. Authorities cited WeChat Nearby (Friend Radar) and the spread of pornographic content as the reason of censorship.

The Committee for Determining Instances of Criminal Content (a working group under the supervision of the attorney general) website FAQ says:[126][127]

Because WeChat collects phone data and monitors member activity and because app developers are outside of the country and not cooperating, this software has been blocked, so you can use domestic applications for cheap voice calls, video calls and messaging.

On 4 January 2018, WeChat was unblocked in Iran.[128]

References

- "WeChat APKs". APKMirror. Android Police. 19 November 2018. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- It's time for messaging apps to quit the bullshit numbers and tell us how many users are active Archived 29 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. techinasia.com. 23 January 2014. Steven Millward.

- "WeChat's world". The Economist. 16 August 2016. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "WeChat now has over 1 billion active monthly users worldwide · TechNode". TechNode. 5 March 2018. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- "Tencent's Profit Is Better Than Expected". Bloomberg.com. 15 November 2017. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "WeChat users pass 900 million as app becomes integral part of Chinese lifestyle". The Drum. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "How WeChat Became China's App For Everything". Fast Company. 2 January 2017. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Cockerell, Isobel (9 May 2019). "Inside China's Massive Surveillance Operation". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- Dou, Eva (8 December 2017). "Jailed for a Text: China's Censors Are Spying on Mobile Chat Groups". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- McDonell, Stephen (7 June 2019). "WeChat and the Surveillance State". BBC. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- 人的監視から混合型監視へ 超万能WeChatの中国をモデルにする北朝鮮(3/3). KoreaWorldTimes (in Japanese). 7 August 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Deibert, Ronald. "Opinion | WeChat users outside China face surveillance while training censorship algorithms". Washington Post. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "China: World Leader of Internet Censorship". Human Rights Watch. 3 June 2011. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Sonnad, Nikki (17 April 2017). "What happens when you try to send politically sensitive messages on WeChat". Quartz (publication). Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Millward, Steven (10 January 2013). "Now China's WeChat App is Censoring Its Users Globally". Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Muncaster, Phil (11 January 2013). "China censors chat users outside China". The Register. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "We Chat, They Watch: How International Users Unwittingly Build up WeChat's Chinese Censorship Apparatus". The Citizen Lab. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Sharma, Kiran (4 August 2020). "Indian apps soar after ban on China's TikTok, WeChat and Baidu: Relations soured by Ladakh clash force Modi to refocus economic struggle". The Nikkei. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Arbel, Tali (6 August 2020). "Trump bans dealings with Chinese owners of TikTok, WeChat". Associated Press. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Loretta Chao, Paul Mozur (19 November 2012). "Zhang Xiaolong, Wechat founder". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- "Archived copy" 微信进行时:厚积薄发的力量. 环球企业家. 13 January 2012. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "E-commerce in China; Industry Report" (PDF). ECOVIS R&G Consulting Ltd. (Beijing) and Advantage Austria. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Chen, Xiaomeng (陈小蒙) (7 November 2012). "Archived copy" 微信:走出中国,走向世界?. 36氪. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Millward, Steven (18 March 2015). "WeChat now has 500 million monthly active users". Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Millward, Steven (12 August 2015). "WeChat rockets to 600M monthly users". Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Custer, C. (18 April 2016). "WeChat blasts past 700 million monthly active users, tops China's most popular apps". Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "WeChat breaks 700 million monthly active users". BI Intellegence. Business Insider. 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Yang, Yuan (18 May 2017). "Tencent scores with domination of mobile gaming". FinancialTimes. p. 15. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Liu, Yujing (3 October 2017). "Tencent eyes US for new growth in social media ad business". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "The Most Popular Messaging App in Every Country". 24 May 2016. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- How China Is Changing Your Internet - The New York Times on YouTube Published on 9 August 2016

- "Welcome to WeChat". WeChat. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "The Sticker Wars: WeChat's creatives go up against Line (updated)". 5 February 2014. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- Fang, Yu (方雨) (4 November 2014). "Archived copy" 微信公众号已经进入标配期. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 3139. "Archived copy" 北京8家医院年内推出微信挂号服务 可挂专家号. people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" 港澳通行证续签新"技能":微信续签送红包!. tongyue.com. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" 信用卡智能"微客服". Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Graziani, Thomas (11 December 2019). "WeChat Official Account: a simple guide". Walkthechat. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- "Archived copy" 你不知道的微信朋友圈分组权限真相 - 人人都是产品经理. www.woshipm.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Chan, Connie (6 August 2015). "When One App Rules Them All: The Case of WeChat and Mobile in China". Andreessen Horowitz. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018.

- "You Can Now Add a Foreign Credit Card on WeChat". 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "WeChat now supports payments between users and one-click payments | Finance Magnates". Fin Tech | Finance Magnates. 24 June 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- European Central Bank (24 February 2018). "Definition of instant payment system". Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- "How Social Cash Made WeChat The App For Everything". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Sun, Eric (22 April 2016). "WeChat Pay invests USD 15 M to support its service providers". AllChinaTech. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Jacobs, Harrison (26 May 2018). "One photo shows that China is already in a cashless future". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "The Truth About The New WeChat Service Charge". 18 February 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Jason (14 April 2019). "WeChat Pay UK - What's The Future Of WeChat Payments". QPSoftware. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Chandler, Clay (13 May 2017). "Tencent and Alibaba Are Engaged in a Massive Battle in China". Fortune. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Yeung, Raymond. "Contactless competition: WeChat Pay is coming to the MTR". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Munger, Charlie. "Berkshire Hathaway 2018 Annual shareholders meeting - 11 May 2018 Afternoon session". Warren Buffett Archive. CNBC/Berkshire Hathway. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Lopez, Napier (18 April 2016). "WeChat just launched a Slack competitor, but there's a catch". The Next Web. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- "WeChat Enterprise could be the app to take down Slack". Digital Trends. 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Hook, Leslie. "Tencent's WeChat uses its muscle to appeal to business users". Financial Times. ISSN 0307-1766. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Osawa, Juro (18 April 2016). "Tencent Targets Corporate Clients With Enterprise We Chat Launch". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- Russell, Jon. "China's Tencent takes on the App Store with launch of 'mini programs' for WeChat". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Brief Tutorial - WeChat Open Platform". open.wechat.com. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Chinese company takes aim at Apple & Google app stores with WeChat app". www.thenews.com.pk. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "This addictive mobile game hooked 100 million users in just two weeks". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "How WeChat became the primary news source in China". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "为什么很多人把微信称做VX? - 知乎". www.zhihu.com. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Horwitz, Josh. "WeChat's new heat map feature lets users—and Chinese authorities—see where crowds are forming". Quartz. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- "In direct challenge to Skype, WeChat now lets users call mobile phones and landlines | VentureBeat". venturebeat.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- Tencent, IBG. ""WeChat Out" VOIP Feature Now Rapidly Expanding Around the World | WeChat Blog: Chatterbox". WeChat Blog: Chatterbox. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- Liping, Zhang (24 March 2017). "'WeChat Index' Opens Opaque Social Network Up to Marketers". Sixth Tone. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Yang, Yuang; Yang, Yingzhi (18 May 2017). "Tencent pushes into news feed and search in challenge to Baidu". Financial Times. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Iyer, Maitrayee. "WeChat introduces Friends Radar to add friends to your list with a tap - Latest Tech News, Video & Photo Reviews at BGR India". Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- "Tech in Asia - Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem". www.techinasia.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- jknotts (13 June 2020). "What's New WeChat: ID Changes Allowed Once per Year, New Algorithms, and Kuaidi Tracking". www.thebeijinger.com. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- help.wechat.com https://help.wechat.com/cgi-bin/micromsg-bin/oshelpcenter?opcode=2&plat=ios&lang=en&id=1208117b2mai141024BRjYBZ#:~:text=WeChat%20ID%20must%20be%20between,be%20changed%20once%20per%20year. Retrieved 16 July 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Yang, Shuai; Chen, Sixing; Li, Bin (15 July 2016). "The Role of Business and Friendships on WeChat Business: An Emerging Business Model in China". Journal of Global Marketing. 29 (4): 174–187. doi:10.1080/08911762.2016.1184363. ISSN 0891-1762.

- Zhixiao, Wang. "Archived copy" 浅谈移动互联时代的微商创业-【维普网】-仓储式在线作品出版平台-www.cqvip.com. www.cqvip.com. cqvip.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Chan, Connie (6 August 2015). "When One App Rules Them All: The Case of WeChat and Mobile in China". Andreessen Horowitz. Andreessen Horowitz. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Peng, Yubing (彭雨冰) (2014). "Archived copy" 论微商的定义和现状-【维普网】-仓储式在线作品出版平台-www.cqvip.com. www.cqvip.com. 12X (智富时代): 29. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jasmine, Lu (15 January 2014). "From Handbags To Wine, China's Luxury Counterfeiters Flee To WeChat | Jing Daily". Jing Daily. Jing Daily. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- C, Custer (13 April 2015). "Tech in Asia - Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem". www.techinasia.com (techinasia.com). techinasia.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Archived copy" 关于"微商"购物维权难引发的思考——以微信平台为例. 现代商业. 0 (2): 29–30. 2015. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Weng, Chuzhe (翁矗哲) (2015). "Archived copy" 基于微商的发展现状管窥微商未来的发展-【维普网】-仓储式在线作品出版平台-www.cqvip.com. www.cqvip.com. 3 (商场现代化): 79–80. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" 微信朋友圈新功能真会玩:发红包才能看照片 | 雷锋网. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mau, Dhani (10 August 2015). "HOW WESTERN FASHION BRANDS ARE USING SOCIAL MEDIA IN CHINA". Fashionista. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- "Michael Kors' WeChat Selfie Competition Shows New York Heritage". Jing Daily. 4 May 2016. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- "Archived copy" 美即抢先一步"勾搭"papi酱 欧莱雅破得了中国品牌收购即毁灭的魔咒吗_聚美丽. www.jumeili.cn (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Doland, Angela (2017). "Papi Jiang, Video Blogger, Comedian". AdAge. Archived from the original on 20 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Murgia, Madhumita (31 March 2017). "WeChat offers UK groups platform to sell goods in China". Financial Times. p. 18. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- "WeChat App". Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- "WeChat is not working on Windows Phone anymore". Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- "WeChat is dropping its Windows Phone app". Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Mittal Mandalia (28 February 2014). "WeChat announces native Mac client; Windows version may follow soon". techienews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "WeChat for Windows". Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- "Archived copy" 登陆依然需要手机扫描二维码 (in Chinese). Sohu IT. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Web WeChat". qq.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Archived copy" 安卓模拟器被全面封杀 微信开放性再引质疑. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Zhang, Xin; Dai, Si (29 November 2015). "The Functionalities of Mobile Applications, Case Study: WeChat (Thesis)" (PDF). Lahti University of Applied Sciences. Lahti, Finland: Faculty of Business Studies' Degree programme in Business Information Technology. p. 39. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Nay, Josh Robert (27 May 2015). "WeChat Version 6.2 for iOS and Android Brings Moments Translation, Chat Log Migration, and More". TruTower. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Nicola Davison. "WeChat: the Chinese social media app that has dissidents worried". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Stilgherrian (29 June 2020). "China's influence via WeChat is 'flying under the radar' of most Western democracies". ZDNet. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "WeChat is a threat to national security claim researchers - ParityNews". ParityNews. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Lyer, Maitrayee (9 June 2014). "WeChat introduces Friends Radar to add friends to your list with a tap". Latest Tech News, Video & Photo Reviews. BGR India. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- "Australia's Defence Department bans WeChat". 11 March 2018. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- "China's tech giants struggle with data privacy amid push into US". Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- "The WeChat revolution: China's 'killer app' for mass communication". NDTV Gadgets. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Chinese Mobile Messaging App WeChat Still A Big Worry For The Indian Government". lighthouseinsights.in. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Parker, Emily. "The popularity of WeChat in China raises the question: why not in the U.S.?".

- Grigg, Angus (22 February 2018). "WeChat's privacy issues mean you should delete China's No. 1 messaging app". The Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Greenburg, Andy. "Hacker Lexicon: What Is End-to-End Encryption?". Wired.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Document". www.amnesty.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- Mukherjee, Riddhi. "It's official, WeChat shares private user data with the Chinese government". www.medianama.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- "WeChat - Privacy Policy". WeChat. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Xiao, Eva (8 May 2020). "China's WeChat Monitors Foreign Users to Refine Censorship at Home". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Study: WeChat Content Outside China Used for Censorship". The New York Times. Associated Press. 7 May 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Mudie, Luisetta, ed. (11 August 2020). "WeChat 'Extends China's Internet' to Wherever Users Are in The World". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- "Tencent's WeChat is a Threat to Everyone". Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "XcodeGhost Q&A". Apple. 23 September 2015. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Claud, Xiao (17 September 2015). "Novel Malware XcodeGhost Modifies Xcode, Infects Apple iOS Apps and Hits App Store". Palo Alto Networks. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Claud, Xiao (18 September 2015). "Malware XcodeGhost Infects 39 iOS Apps, Including WeChat, Affecting Hundreds of Millions of Users". Palo Alto Networks. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Reed, Thomas (21 September 2015). "XcodeGhost malware infiltrates App Store". Malwarebytes. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Claud, Xiao (18 September 2015). "Update: XcodeGhost Attacker Can Phish Passwords and Open URLs through Infected Apps". Palo Alto Networks. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- DelhiJune 29, Rahul Shrivastava New; June 29, 2020UPDATED:; Ist, 2020 22:21. "Govt bans 59 Chinese apps including TikTok as border tensions simmer in Ladakh". India Today. Retrieved 29 June 2020.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Abi-Habib, Maria (29 June 2020). "India Bans Nearly 60 Chinese Apps, Including TikTok and WeChat". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Millward, Steven (11 January 2013). "Tencent Responds in Case of Apparent WeChat Censorship". Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Blackwell, Tom (4 December 2019). "Censored by a Chinese tech giant? Canadians using WeChat app say they're being blocked". National Post. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Schiffer, Zoe. "WeChat keeps banning Chinese Americans for talking about Hong Kong". The Verge. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Zhou, Cissy (3 March 2020). "How WeChat censored even neutral messages about the coronavirus in China". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "One App, Two Systems: How WeChat uses one censorship policy in China and another internationally". Citizen Lab. 30 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "WeChat: Domains Need ICP License Before Being Shared (Chinese)". QQ.com. 12 December 2014. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- "Iran bans another social network, blocks WeChat messaging app". Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- کارگروه تعیین مصادیق محتوای مجرمانه - Internet.ir (in Persian). 24 December 2013. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- "Archived copy" فیلتر پیامرسان 'ویچت' در ایران برداشته شد. BBC Persian (in Persian). 2018. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)