Toussaint Louverture

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (French: [fʁɑ̃swa dɔminik tusɛ̃ luvɛʁtyʁ]; also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda; 1743 – 7 April 1803) was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. He first fought for the Spanish against the French; then for France against Spain and Great Britain; and finally, he fought on behalf of Saint-Domingue in the era of Napoleonic France. As a leader of the growing resistance, his military and political acumen saved the gains of the first black insurrection in November 1791, helping to transform the slave insurgency into a revolutionary movement. By 1800 Saint-Domingue, the most prosperous French slave colony of the time, had become the first free colonial society to have explicitly rejected race as the basis of social ranking. Louverture is now known as the "Father of Haiti".

Toussaint Louverture | |

|---|---|

Posthumous 1813 painting of Louverture | |

| President of Haiti | |

| In office 7 July 1801 – 6 May 1802 | |

| Appointed by | Constitution of 1801 |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Republic of Haiti) |

| Governor-General of Saint-Domingue | |

| In office 1797–1801 | |

| Appointed by | Étienne Maynaud |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Toussaint de Bréda 1743 Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) |

| Died | 7 April 1803 (aged 59)[1] Fort-de-Joux, France |

| Nationality | Haitian |

| Spouse(s) | Suzanne Simone Baptiste Louverture |

| Signature | |

| Nickname(s) | Napoléon Noir[2] Black Spartacus[3][4] |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | French Army French Revolutionary Army Armée Indigène[5] |

| Years of service | 1791–1803 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Haitian Revolution |

Already a free man and a Jacobin, Louverture began his military career as a leader of the 1791 slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue.[6] Initially allied with the Spaniards of neighboring Santo Domingo, Louverture switched allegiance to the French when the new government abolished slavery. He gradually established control over the whole island and used political and military tactics to gain dominance over his rivals. Throughout his years in power, he worked to improve the economy and security of Saint-Domingue. Worried about the economy, which had stalled, he restored the plantation system using paid labour; negotiated trade treaties with the United Kingdom and the United States; and maintained a large and well-disciplined army.[7] Although Louverture did not sever ties with France in 1800 after defeating leaders among the free people of color, he promulgated an autonomous constitution for the colony in 1801, which named him as Governor-General for Life, even against Napoleon Bonaparte's wishes.[8]

In 1802, he was invited to a parley by French Divisional General Jean-Baptiste Brunet, and was arrested under false pretenses. He was deported to France and jailed at Fort de Joux in a cell without a roof. Deprived of food and water, he died in 1803. Though Louverture died betrayed before the final and most violent stage of the armed conflict, his achievements set the grounds for the black army's absolute victory. Suffering massive losses in multiple historic battles at the hands of the Haitian army and losing many men of their forces to yellow fever, the French capitulated and withdrew permanently from Saint-Domingue that very year. The Haitian Revolution continued under Louverture's lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who declared independence on 1 January 1804, thereby establishing the sovereign state of Haiti.

Early life

Birth and childhood

Little is known about Toussaint Louverture's early life, as there are contradictory accounts and evidence regarding his time before the advent of the Haitian Revolution. The earliest records are his recorded remarks and the reminiscences of his second legitimate son, Isaac Louverture.[9]

Louverture is thought to have been born on the plantation of Bréda at Haut de Cap in Saint-Domingue, which was owned by the Comte de Noé and later managed by Bayon de Libertate.[10] An alternative explanation of Louverture's origins is that he was brought to Bréda by the new overseer Bayon de Libertate, who took up his duties in 1772.[11]

His date of birth is also uncertain, as various sources have given birth dates between 1739 and 1746. However, his name suggests that he was born on All Saints' Day: 1 November. Accordingly, he was probably about 50 at the start of the revolution in 1791. Still, because of the lack of written records, Louverture may not have known his exact birth date.[12]

Though he would become known for his stamina and riding prowess, in childhood, he earned the nickname Fatras-Bâton ('clumsy stick'), suggesting he was small and weak.[13][14]:26–7 John Relly Beard's biography of Louverture claims that family traditions name his grandfather as Gaou Guinou, a son of the King of Allada. While Louverture's parents are not known, he himself was the eldest of several children,[14]:23–4 while Pierre Baptiste Simon is usually considered to have been his godfather.[15]

Education

Louverture is believed to have been well educated by his godfather Pierre Baptiste, a free person of color who lived and worked on the Bréda plantation. Historians have speculated as to Louverture's intellectual background. His extant letters demonstrate a command of French in addition to Creole; and he reveals familiarity with Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher who had lived as a slave. His public speeches as well as his life's work, according to his biographers, show a familiarity with Machiavelli.[16]

Some cite Abbé Raynal, who wrote against slavery, as a possible influence.[16][14]:30–6 The wording of the proclamation issued by then rebel slave leader Louverture on 29 August 1793, which may have been the first time he publicly used the name "Louverture", seems to refer to an anti-slavery passage in Abbé Raynal's "A Philosophical and Political History of the Settlements and Trade of the Europeans in the East and West Indies."[17][18]

He may also have received some education from Jesuit missionaries. His medical knowledge is attributed to familiarity with African or Creole herbal-medical techniques, as well techniques commonly found in Jesuit-administered hospitals.[19] A few legal documents signed on Louverture's behalf between 1778 and 1781 suggest that he could not write at that time.[20][21]:61–7 Throughout his military and political career, he used secretaries to prepare most of his correspondence. A few surviving documents in his own hand confirm that he could write, although his spelling in the French language was "strictly phonetic."[22]

Marriage and children

In 1782, Louverture married Suzanne Simone Baptiste, who is thought to have been his cousin or the daughter of his godfather.[21]:263 Toward the end of his life, he told General Caffarelli that he had fathered sixteen children with multiple women, of whom eleven had predeceased him.[21]:264–7 Not all his children can be identified for certain, but his three legitimate sons are well known. The eldest, Placide, was probably adopted by Louverture and is generally thought to have been Suzanne's first child, fathered by Seraphim Le Clerc, a mulatto. The two sons born of his marriage with Suzanne were Isaac and Saint-Jean.[21]:264–7

Slavery, freedom and working life

"I was born a slave, but nature gave me the soul of a free man."[23]

Until 1938, historians believed that Louverture had been a slave until the start of the revolution.[note 1] In the later 20th century, discovery of a marriage certificate dated 1777 documents that he was freed in 1776 at the age of 33. This find retrospectively clarified a letter of 1797, in which he said he had been free for twenty years.[21]:62 He appeared to have an important role on the Bréda plantation until the outbreak of the revolution, presumably as a salaried employee who contributed to the daily functions of the plantation.[24] He had initially been responsible for the livestock.[25] By 1791, his responsibilities most likely included acting as coachman to the overseer, de Libertat, and as a slave-driver, charged with organising the workforce.[26]

As a free man, Louverture began to accumulate wealth and property. Surviving legal documents show him renting a small coffee plantation that was worked by a dozen of his own slaves.[27] He would later say that by the start of the revolution, he had acquired a reasonable fortune, and was the owner of a number of properties and slaves at Ennery.[28]

Louverture's life philosophy, as a revolutionary spirit, not only incited widespread recognition of autonomy among his enslaved counterparts but evoked a collective sense of worry among colonialist nations, such as Great Britain, which feared the slave revolt and ideology would spread to other slave societies in the Caribbean.[29] In light of the given circumstance, "England found the French army preferable to the enlightened to Toussaint Louverture, while the United States, only just free of its own colonial oppression, opted to ally with the colonial powers of England and France rather than to give aid to Saint-Dominques's anti-colonial struggle."[29]

Haitian Revolution

The Rebellion: 1791–1794

Beginning in 1789, free people of color of Saint-Domingue were inspired by the French Revolution to seek an expansion of their rights and equality, while perpetuating the denial of freedom and rights to the slaves, who made up the overwhelming majority of population on the island. Initially, the slave population did not become involved in the conflict.[30] In August 1791, a Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman marked the start of a major slave rebellion in the north, which had the largest plantations and masses of slaves. Louverture apparently did not take part in the earliest stages of the rebellion, but after a few weeks he sent his family to safety in Spanish Santo Domingo and helped the overseers of the Breda plantation to leave the island. He joined the forces of Georges Biassou as doctor to the troops, commanding a small detachment.[31] Surviving documents show him participating in the leadership of the rebellion, discussing strategy, and negotiating with the Spanish supporters of the rebellion for supplies.[24]

In December 1791, he was involved in negotiations between rebel leaders and the French Governor, Blanchelande, for the release of their white prisoners and a return to work in exchange for a ban on the use of the whip, an extra non-working day per week, and freedom for a handful of leaders.[32] When the offer was rejected, he was instrumental in preventing the massacre of Biassou's white prisoners.[33] The prisoners were released after further negotiations with the French commissioners and taken to Le Cap by Louverture. He hoped to use the occasion to present the rebellion's demands to the colonial assembly, but they refused to meet with him.[34]

Throughout 1792, as a leader in an increasingly formal alliance between the black rebellion and the Spanish, Louverture ran the fortified post of La Tannerie and maintained the Cordon de l'Ouest, a line of posts between rebel and colonial territory.[35] He gained a reputation for running an orderly camp, trained his men in guerrilla tactics and "the European style of war,"[36] and began to attract soldiers who would play an important role throughout the revolution.[37] After hard fighting, he lost La Tannerie in January 1793 to the French General Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux, but it was in these battles that the French first recognised him as a significant military leader.[38]

Some time in 1792–93, he adopted the surname Louverture, from the French word for "opening" or "the one who opened the way".[39] Although some modern writers spell his adopted surname with an apostrophe, as in "L'Ouverture", he did not, as his extant correspondence indicates. The most common explanation is that it refers to his ability to create openings in battle. The name is sometimes attributed to French commissioner Polverel's exclamation: "That man makes an opening everywhere". However, some writers think the name referred to a gap between his front teeth.[40]

Despite adhering to royalist political views, Louverture had begun to use the language of freedom and equality associated with the French Revolution.[41] From being willing to bargain for better conditions of slavery late in 1791, he had become committed to its complete abolition.[42]

After an offer of land, land, privileges, and recognising the freedom of slave soldiers and their families, Jean-Francois and Biassou formally allied with the Spanish in May 1793. It is likely Louverture did soon after in early June. He had made covert overtures to General Laveaux prior but was rebuffed as Louverture’s conditions for alliance were deemed unacceptable. At this time the republicans were yet to make any formal offer to the slaves in arms and conditions for the blacks under the Spanish looked better than that of the French.[43] In response to the civil commissioners’ radical 20 June proclamation (not a general emancipation but an offer of freedom to male slaves who agreed to fight for them) Louverture stated that “the blacks wanted the serve under a king and the Spanish king offered his protection”.[44]

On 29 August 1793 he made his famous declaration of Camp Turel to the blacks of St Domingue:

Brothers and friends, I am Toussaint Louverture; perhaps my name has made itself known to you. I have undertaken vengeance. I want Liberty and Equality to reign in St Domingue. I am working to make that happen. Unite yourselves to us, brothers and fight with us for the same cause.

Your very humble and obedient servant, Toussaint Louverture,

General of the armies of the king, for the public good.[45]

On the same day, the beleaguered French commissioner, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, proclaimed emancipation for all slaves in French Saint-Domingue,[46] hoping to bring the black troops over to his side.[47] Initially, this failed, perhaps because Louverture and the other leaders knew that Sonthonax was exceeding his authority.[48]

However, on 4 February 1794, the French revolutionary government in France proclaimed the abolition of slavery.[49] For months, Louverture had been in diplomatic contact with the French general Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux. During this time, competition between him and other rebel leaders was growing, and the Spanish had started to look with disfavour on his near-autonomous control of a large and strategically important region.[50]

Louverture's auxiliary force was employed to great success, with his army responsible for half of all Spanish gains north of the Artibonite in the West in addition to capturing the port town of Gonaïves in December 1793.[51] However, tensions had emerged between Louverture and the Spanish higher-ups. His superior with whom he enjoyed good relations, Matías de Armona, was replaced Juan de Lleonart – who was disliked by the black auxiliaries. Lleonart failed to support Louverture in March 1794 during his feud with Biassou, who had been stealing supplies for Louverture's men and selling their families as slaves. Unlike Jean-Francois and Bissaou, Louverture refused to round up enslaved women and children to sell to the Spanish. This feud also emphasised Louverture's inferior position in the trio of black generals in the minds of the Spanish – a check upon any ambitions for further promotion.[52]

On 29 April 1794 the Spanish garrison at Gonaïves was suddenly attacked by black troops fighting in the name of "the King of the French", who demanded that the garrison surrender. Around 150 men were killed and much of the populace forced to flee. White guardsmen in the surrounding area had been murdered, and Spanish patrols sent into the area never returned.[53] Louverture is suspected to be behind this attack, though was not present. He wrote to the Spanish 5 May protesting his innocence – supported by the Spanish commander of the Gonaïves garrison, who noted that his signature was absent from the rebels' ultimatum. It was not until 18 May that Louverture would claim responsibility for the attack, when he was fighting under the banner of the French.[54]

The events at Gonaïves made Lleonart increasingly suspicious of Louverture. When they had met at his camp 23 April, the black general had shown up with 150 armed and mounted men as opposed to the usual 25, choosing not to announce his arrival or waiting for permission to enter. Lleonart found him lacking his usual modesty or submission, and after accepting an invitation to dinner 29 April, Louverture afterwards failed to show. The limp that had confined him to his bed during the Gonaïves attack was thought to be feigned and Lleonart suspecting him of turning coat.[55] Remaining distrustful of the black commander; Lleonart kept his wife and children under house whilst Louverture led an attack on Dondon in early May, an act which Lleonart later believed confirmed Louverture's decision to turn against the Spanish.[56]

Alliance with the French: 1794–1796

The timing of and motivation behind Louverture’s volte-face against Spain remains debated amongst historians. James claimed that upon learning of the emancipation decree in May 1794, Louverture decided to join the French in June.[57] It is argued by Ardouin that Toussaint was indifferent towards black freedom, concerned primarily for his own safety and resentful over his treatment by the Spanish – leading him to officially join the French 4 May 1794 when he raised the republican flag over Gonaïves.[58] Ott sees Louverture as "both a power-seeker and sincere abolitionist" that was working with Laveaux since January 1794 and switched sides 6 May.[59]

Louverture himself afterwards claimed to have switched sides after emancipation was proclaimed and the commissioners Sonthonax and Polverel had returned to France in June 1794. However, a letter from Toussaint to General Laveaux confirms that he was already officially fighting on the behalf of the French by 18 May 1794.[60]

In the first weeks, Louverture eradicated all Spanish supporters from the Cordon de l'Ouest, which he had held on their behalf.[61] He faced attack from multiple sides. His former colleagues in the black slave rebellion were now fighting against him for the Spanish. As a French commander, he was under attack from the British troops who had landed on Saint-Domingue in September, as the British hoped to take advantage of the instability and gain control of the wealthy sugar-producing island.[62] On the other hand, he was able to pool his 4,000 men with Laveaux's troops in joint actions.[63] By now his officers included men who were to remain important throughout the revolution: his brother Paul, his nephew Moïse, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe.[64]

Before long, Louverture had put an end to the Spanish threat to French Saint-Domingue. In any case, the Treaty of Basel of July 1795 marked a formal end to hostilities between the two countries. Black leaders Jean-François and Biassou continued to fight against Louverture until November, when they left for Spain and Florida, respectively. At that point, most of their men joined Louverture's forces.[65] Louverture also made inroads against the British troops, but was unable to oust them from Saint-Marc. He contained them and rendered them ineffective by returning to guerilla tactics.[66]

Throughout 1795 and 1796, Louverture was also concerned with re-establishing agriculture and exports, and keeping the peace in areas under his control. In speeches and policy he revealed his belief that the long-term freedom of the people of Saint-Domingue depended on the economic viability of the colony.[67] He was held in general respect, and resorted to a mixture of diplomacy and force to return the field hands to the plantations as emancipated and paid workers.[68] Workers regularly created small rebellions, protesting poor conditions, their lack of real freedom, or fearing a return to slavery. They wanted to establish their own small holdings and work for themselves, rather than on plantations.[69]

Another of Louverture's concerns was to manage potential rivals for power within the French part of the colony. The most serious of these was the mulatto commander Jean-Louis Villatte, based in Cap-Français. Louverture and Villate had competed over the command of some sections of troops and territory since 1794. Villatte was thought to be somewhat racist towards black soldiers such as Louverture and planned to ally with André Rigaud, a free man of colour, after overthrowing French General Étienne Laveaux.[70] In 1796 Villate drummed up popular support by accusing the French authorities of plotting a return to slavery.

On 20 March, he succeeded in capturing the French Governor Laveaux, and appointed himself Governor. Louverture's troops soon arrived at Cap-Français to rescue the captured governor and drive Villatte out of town. Louverture was noted for opening the warehouses to the public, proving that they were empty of the chains that residents feared had been imported to prepare for a return to slavery. He was promoted to commander of the West Province two months later, and in 1797 was appointed as Saint-Domingue's top-ranking officer.[71] Laveaux proclaimed Louverture as Lieutenant Governor, announcing at the same time that he would do nothing without his approval, to which Louverture replied, "After God, Laveaux".[72]

Third Commission: 1796–97

A few weeks after Louverture's triumph over the Villate insurrection, France's representatives of the third commission arrived in Saint-Domingue. Among them was Sonthonax, the commissioner who had previously declared abolition of slavery on the same day as Louverture's proclamation of Camp Turel.[73] At first the relationship between the two men was positive. Sonthonax promoted Louverture to general and arranged for his sons, Placide and Isaac, to attend the school that had been established in France for the children of colonials.[74]

In September 1796, elections were held to choose colonial representatives for the French national assembly. Louverture's letters show that he encouraged Laveaux to stand, and historians have speculated as to whether he was seeking to place a firm supporter in France or to remove a rival in power.[75] Sonthonax was also elected, either at Louverture's instigation or on his own initiative. While Laveaux left Saint-Domingue in October, Sonthonax remained.[76]

Sonthonax, a fervent revolutionary and fierce supporter of racial equality, soon rivalled Louverture in popularity. Although their goals were similar, they had several points of conflict.[77] They strongly disagreed about accepting the return of the white planters who had fled Saint-Domingue at the start of the revolution. To Sonthonax, they were potential counter-revolutionaries, to be assimilated, officially or not, with the ‘émigrés’ who had fled the French Revolution and were forbidden to return under pain of death. To Louverture, they were bearers of useful skills and knowledge, and he wanted them back.[78]

In summer 1797, Louverture authorised the return of Bayon de Libertat, the ex-overseer of Bréda, with whom he had a lifelong relationship. Sonthonax wrote to Louverture threatening him with prosecution and ordering him to get Bayon off the island. Louverture went over his head and wrote to the French Directoire directly for permission for Bayon to stay.[79] Only a few weeks later, he began arranging for Sonthonax's return to France that summer.[71] Louverture had several reasons to want to get rid of Sonthonax; officially he said that Sonthonax had tried to involve him in a plot to make Saint-Domingue independent, starting with a massacre of the whites of the island.[80] The accusation played on Sonthonax's political radicalism and known hatred of the aristocratic white planters, but historians have varied as to how credible they consider it.[81]

On reaching France, Sonthonax countered by accusing Louverture of royalist, counter-revolutionary, and pro-independence tendencies.[82] Louverture knew that he had asserted his authority to such an extent that the French government might well suspect him of seeking independence.[83] At the same time, the French Directoire government was considerably less revolutionary than it had been. Suspicions began to brew that it might reconsider the abolition of slavery.[84] In November 1797, Louverture wrote again to the Directoire, assuring them of his loyalty but reminding them firmly that abolition must be maintained.[85]

Treaties with Britain and the United States: 1798

For several months, Louverture was in sole command of French Saint-Domingue, except for a semi-autonomous state in the south, where general André Rigaud had rejected the authority of the third commission.[86] Both generals continued attacking the British, whose position on Saint-Domingue was looking increasingly weak.[87] Louverture was negotiating their withdrawal when France's latest commissioner, Gabriel Hédouville, arrived in March 1798, with orders to undermine his authority.[88]

On 30 April 1798, Louverture signed a treaty with the British general, Thomas Maitland, exchanging the withdrawal of British troops from western Saint-Domingue for an amnesty for the French counter-revolutionaries in those areas. In May, Port-au-Prince was returned to French rule in an atmosphere of order and celebration.[89]

In July, Louverture and Rigaud met commissioner Hédouville together. Hoping to create a rivalry that would diminish Louverture's power, Hédouville displayed a strong preference for Rigaud, and an aversion to Louverture.[90] However, General Maitland was also playing on French rivalries and evaded Hédouville's authority to deal with Louverture directly.[91] In August, Louverture and Maitland signed treaties for the evacuation of the remaining British troops. On 31 August, they signed a secret treaty which lifted the British blockade on Saint-Domingue in exchange for a promise that Louverture would not export the black revolution to the British colony of Jamaica, which also used slaves to produce sugar.[92]

As Louverture's relationship with Hédouville reached the breaking point, an uprising began among the troops of his adopted nephew, Hyacinthe Moïse. Attempts by Hédouville to manage the situation made matters worse and Louverture declined to help him. As the rebellion grew to a full-scale insurrection, Hédouville prepared to leave the island, while Louverture and Dessalines threatened to arrest him as a troublemaker.[93] Hédouville sailed for France in October 1798, nominally transferring his authority to Rigaud. Louverture decided instead to work with Phillipe Roume, a member of the third commission who had been posted to the Spanish parts of the colony.[94] Though Louverture continued to protest his loyalty to the French government, he had expelled a second government representative from the territory and was about to negotiate another autonomous agreement with one of France's enemies.[95]

The United States had suspended trade with France in 1798 because of increasing conflict over piracy. The two countries were almost at war, but trade between Saint-Domingue and the United States was desirable to both Louverture and the United States. With Hédouville gone, Louverture sent Joseph Bunel to negotiate with the government of John Adams. The terms of the treaty were similar to those already established with the British, but Louverture continually resisted suggestions from either power that he should declare independence.[96] As long as France maintained the abolition of slavery, he appeared to be content to have the colony remain French, at least in name.[97]

Expansion of territory: 1799–1801

In 1799, the tensions between Louverture and Rigaud came to a head. Louverture accused Rigaud of trying to assassinate him to gain power over Saint-Domingue for himself. Rigaud claimed Louverture was conspiring with the British to restore slavery.[98] The conflict was complicated by racial overtones which escalated tension between blacks and mulattoes.[99][100] Louverture had other political reasons for bringing down Rigaud. Only by controlling every port could he hope to prevent a landing of French troops if necessary.[101]

After Rigaud sent troops to seize the border towns of Petit-Goave and Grand-Goave in June 1799, Louverture persuaded Roume to declare Rigaud a traitor and attacked the southern state.[102] The resulting civil war, known as the War of Knives, lasted over a year, with the defeated Rigaud fleeing to Guadeloupe, then France, in August 1800.[103] Louverture delegated most of the campaign to his lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who became infamous, during and after the war, for massacring mulatto captives and civilians.[104] The number of deaths is contested: the contemporary French general François Joseph Pamphile de Lacroix suggested 10,000 deaths, while the 20th-century Trinidadian historian C.L.R. James later claimed there were only a few hundred deaths in contravention of the amnesty.[105]

In November 1799, during the civil war, Napoleon Bonaparte gained power in France and passed a new constitution declaring that the colonies would be subject to special laws.[106] Although the colonies suspected this meant the re-introduction of slavery, Napoleon began by confirming Louverture's position and promising to maintain abolition.[107] But he also forbade Louverture to invade Spanish Santo Domingo, an action that would put Louverture in a powerful defensive position.[108] Louverture was determined to proceed anyway and coerced Roume into supplying the necessary permission.[109]

In January 1801, Louverture and Hyacinthe Moïse invaded the Spanish territory, taking possession from the Governor, Don Garcia, with few difficulties. The area had been less developed and less densely populated than the French section. Louverture brought it under French law, which abolished slavery, and embarked on a program of modernization. He was now master of the whole island.[110]

Constitution of 1801

Napoleon had informed the inhabitants of Saint-Domingue that France would draw up a new constitution for its colonies, in which they would be subjected to special laws.[111] Despite his initial protestations to the contrary, the former slaves feared that he might restore slavery. In March 1801, Louverture appointed a constitutional assembly, composed chiefly of white planters, to draft a constitution for Saint-Domingue. He promulgated the Constitution on 7 July 1801, officially establishing his authority over the entire island of Hispaniola. It made him Governor-General for Life with near absolute powers and the possibility of choosing his successor. However, Louverture was not to explicitly declare Saint-Domingue's independence, acknowledging in Article 1 that it was a single colony of the French Empire.[112] Article 3 of the constitution states: "There cannot exist slaves [in Saint-Domingue], servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French."[113] The constitution guaranteed equal opportunity and equal treatment under the law for all races, but also confirmed Louverture's policies of forced labour and the importation of workers through the slave trade.[114] Louverture was not willing to compromise Catholicism for Vodou, the dominant faith among former slaves. Article 6 states that "the Catholic, Apostolic, Roman faith shall be the only publicly professed faith."[115]

Louverture charged Colonel Charles Humbert Marie Vincent with the task of presenting the new constitution to Napoleon, although Vincent was apalled by what Louverture had done. Several aspects of the constitution were damaging to France: the absence of provision for French government officials, the lack of advantages to France in trade with its own colony, and Louverture's breach of protocol in publishing the constitution before submitting it to the French government. Despite his disapproval, Vincent attempted to submit the constitution to Napoleon, but was briefly exiled to Mediterranean island of Elba for his pains.[116][note 2]

Louverture identified as a Frenchman and strove to convince Bonaparte of his loyalty. He wrote to Napoleon but received no reply.[118] Napoleon eventually decided to send an expedition of 20,000 men to Saint-Domingue to restore French authority, and possibly to restore slavery as well.[119] Given the Treaty of Amiens (March 1802–May 1803) with Great Britain, Napoleon was suddenly able to plan this operation without the risk of interception by the Royal Navy.

Leclerc's campaign

.jpg)

Napoleon's troops, under the command of his brother-in-law, General Charles Emmanuel Leclerc, were directed to seize control of the island by diplomatic means, proclaiming peaceful intentions, and keep secret his orders to deport all black officers.[120] Meanwhile, Louverture was preparing for defence and ensuring discipline. This may have contributed to a rebellion against forced labor led by his nephew and top general, Moïse, in October 1801. Because the activism was violently repressed, when the French ships arrived, not all of Saint-Domingue was automatically on Louverture's side.[121] In late January 1802, while Leclerc sought permission to land at Cap-Français and Christophe held him off, the Vicomte de Rochambeau suddenly attacked Fort-Liberté, effectively quashing the diplomatic option.[122] Christophe had written to Leclerc: "you will only enter the city of Cap, after having watched it reduced to ashes. And even upon these ashes, I will fight you."

Louverture's plan in case of war was to burn the coastal cities and as much of the plains as possible, retreat with his troops into the inaccessible mountains, and wait for yellow fever, which flourished on a seasonal basis, to decimate the European troops.[123] The biggest impediment to this plan proved to be difficulty in internal communications. Christophe burned Cap-Français and retreated, but Paul Louverture was tricked by a false letter into allowing the French to occupy Santo Domingo; other officers believed Napoleon's diplomatic proclamation, while some attempted resistance instead of burning and retreating.[124] French reports to Napoleon show that in the months of fighting that followed, the French felt their position was weak, but that Louverture and his generals did not fully realize their strength.[125]

With both sides shocked by the violence of the initial fighting, Leclerc tried belatedly to revert to the diplomatic solution. Louverture's sons and their tutor had been sent from France to accompany the expedition with this end in mind and were now sent to present Napoleon's proclamation to Louverture.[126] When these talks broke down, months of inconclusive fighting followed.

But this all ended when Christophe, ostensibly convinced that Leclerc would not reinstitute slavery, switched sides in return for retaining his generalship in the French military. General Jean-Jacques Dessalines did the same a short time later. On 6 May 1802, Louverture rode into Cap-Français, and negotiated an acknowledgement of Leclerc's authority, in return for amnesty for himself and all his remaining generals. He thus ended hostilities and retired to his plantation in Ennery.[127]

Arrest, imprisonment, and death

Jean-Jacques Dessalines was at least partially responsible for Louverture's arrest, as asserted by several authors, including Louverture's son Isaac. On 22 May 1802, after Dessalines learned that Louverture had failed to instruct a local rebel leader to lay down his arms per the recent ceasefire agreement, he immediately wrote to Leclerc to denounce Louverture's conduct as "extraordinary." For this action, Dessalines and his spouse received gifts from Jean Baptiste Brunet.[128]

Leclerc originally asked Dessalines to arrest Louverture, but he declined. Jean Baptiste Brunet was ordered to do so, but accounts differ as to how he accomplished this. One version said that Brunet pretended that he planned to settle in Saint-Domingue and was asking Louverture's advice about plantation management. Louverture's memoirs, however, suggest that Brunet's troops had been provocative, leading Louverture to seek a discussion with him. Either way, Louverture had a letter, in which Brunet described himself as a "sincere friend", to take with him to France. Embarrassed about his trickery, Brunet absented himself during the arrest.[129] Brunet deported Louverture and his aides to France on the frigate Créole and the 74-gun Héros, claiming that he suspected the former leader of plotting an uprising. Boarding Créole, Toussaint Louverture warned his captors that the rebels would not repeat his mistake:[130]

In overthrowing me you have cut down in Saint Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty; it will spring up again from the roots, for they are numerous and they are deep.[131]

The ships reached France on 2 July 1802 and, on 25 August, Louverture was sent to the jail in Fort-de-Joux in Doubs. While in prison, he died on 7 April 1803. Suggested causes of death include exhaustion, malnutrition, apoplexy, pneumonia, and possibly tuberculosis.[132][133]

Views and stances

Religion and spirituality

Throughout his life, Louverture was known as a devout Roman Catholic.[134] After defeating forces led by Andre Rigaud in the War of the Knives, Louverture consolidated his power by decreeing a new constitution for the colony in 1801. It established Catholicism as the official religion. Although Vodou was generally practiced on Saint-Domingue in combination with Catholicism, little is known for certain if Louverture had any connection with it. Officially as ruler of Saint-Domingue, he discouraged it.[135]

Historians have suggested that he was a member of high degree of the Masonic Lodge of Saint-Domingue, mostly based on a Masonic symbol he used in his signature. The membership of several free blacks and white men close to him has been confirmed.[136] His membership is, considering his status as a devout Catholic, nonetheless unlikely due to the papal ban on Catholics holding membership in Masonic organizations introduced by Pope Clement XII having gone into effect in 1738.[137]

Legacy

Influence

In his absence, Jean-Jacques Dessalines led the Haitian rebellion until its completion, finally defeating the French forces in 1803, after they were seriously weakened by yellow fever; two-thirds of the men had died when Napoleon withdrew his forces.

John Brown claimed influence by Louverture in his plans to invade Harpers Ferry. Brown and his band captured citizens, and for a small time the federal armory and arsenal there. Brown's goal was that the local slave population would join the raid, but they did not. Brown was eventually captured and put on trial, and was hanged on 2 December 1859. Brown and his band showed devotion to the violent tactics of the Haitian Revolution. During the 19th century African Americans referred to Louverture as an example of how to reach freedom. Also during the 19th century, British writers focused on Louverture's domestic life and ignored his militancy to show him as an unthreatening rebel slave.[138]

Memorials

On 29 August 1954, the Haitian ambassador to France, Léon Thébaud, inaugurated a stone cross memorial for Toussaint Louverture at the foot of Fort-de-Joux.[139] Years afterward, the French government ceremoniously presented a shovelful of soil from the grounds of Fort-de-Joux to the Haitian government as a symbolic transfer of Louverture's remains.

An inscription in his memory, was installed in 1998 on the wall of the Panthéon in Paris. It reads:[140]

Combattant de la liberté, artisan de l'abolition de l'esclavage, héros haïtien mort déporté au Fort-de-Joux en 1803.

(Combatant for liberty, artisan of the abolition of slavery, Haitian hero died in deportation at Fort-de-Joux in 1803.)

The inscription is opposite a wall inscription, also installed in 1998, honoring Louis Delgrès, a mulatto military leader in Guadeloupe who died leading the resistance against Napoleonic reoccupation and re-institution of slavery on that island. The location of Delgrès' body is also a mystery. Both inscriptions are located near the tombs of Jean Jaurès, Félix Éboué, Marc Schoelcher and Victor Schoelcher.[141]

Cultural references

- English poet William Wordsworth published his sonnet "To Toussaint L'Ouverture" in January 1803.[142]

- African-American novelist Frank J. Webb refers to Louverture in his 1857 novel The Garies and Their Friends, about free African Americans. Louverture's portrait is said to inspire real estate tycoon Mr. Walters.[143]

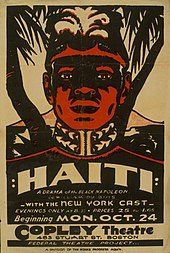

- In 1934, Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James wrote a play entitled Toussaint L'Ouverture. It was performed at the Westminster Theatre in London in 1936 and starred actors Paul Robeson (in the title role), Robert Adams, and Orlando Martins.[144] The play was revised and produced in 1967 as The Black Jacobins (after James's classic 1938 history of that name), and in 1986, Yvonne Brewster directed a production of it at the Riverside Studios as the first play to be staged by the black-led Talawa Theatre Company, with Norman Beaton in the principal role.[145]

- In 1938, American artist Jacob Lawrence created a series of paintings about the life of Louverture, which he later adapted into a series of prints.[146] His painting, titled Toussaint L'Ouverture, hangs in the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio.

- In 1944, African-American writer Ralph Ellison wrote the story "Mister Toussan", in which two African-American youths exaggerate the story of Louverture. He is seen as a symbol of Blacks asserting their identities and liberty over White dominance.[147]

- Kenneth Roberts's best-selling novel, Lydia Bailey (1947), is set during the Haitian Revolution and features Louverture, Dessalines, and Cristophe as the principal historical characters. The 1952 American film based on the novel was directed by Jean Negulesco; Louverture is portrayed by actor Ken Renard.[148]

- In 1977 the opera Toussaint by David Blake was produced by English National Opera at the Coliseum Theatre in London, starring Neil Howlett in the title role.[149]

- In 1983, Jean-Michel Basquiat, the Brooklyn-born New York painter of the 1980s, whose father was from Haiti, painted the monumental work, Toussaint L'Ouverture vs Savonarola, with a portrait of Louverture.[150]

- Haitian actor Jimmy Jean-Louis starred as the title role in the 2012 French miniseries Toussaint Louverture.[151]

Notes and References

Notes

- Up to, for example, C.L.R. James, writing in 1938

- Napoleon himself would later be exiled to Elba after his 1814 abdication.[117]

Citations

- Stephen, James (1814). The history of Toussaint Louverture. Butterworth and son. p. 82.

- Taylor, David (2002). Martini. p. 95. ISBN 1930603037.

- Knight C., ed. (1843). "The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge; Volume 25". p. 96. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Henri Christophe (King of Haiti) (1952). Griggs, Earl Leslie; Prator, Clifford H. (eds.). "Henry Christophe & Thomas Clarkson: A Correspondence". University of California Press. p. 17. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Fombrun, Odette Roy, ed. (2009). "History of The Haitian Flag of Independence" (PDF). The Flag Heritage Foundation Monograph And Translation Series Publication No. 3. p. 13. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Vulliamy, Ed, ed. (28 August 2010). "The 10 best revolutionaries". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Cauna, pp. 7–8

- Popkin, Jeremy D. (2012). A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. p. 114. ISBN 978-1405198219.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 57–58.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 59–60, 62.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 66, 70, 72.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 59–60.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 60, 62.

- Beard, John Relly. [1863] 2001. Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography (online ed.). Boston: James Redpath.

- Korngold, Ralph. [1944] 1979. Citizen Toussaint. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-20794-1.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 61

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 18.

- Blackburn, Robin. 2000. The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery 1776–1848. New York: Verso. p. 54.

- Bell, 2007, pp. 64–65

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 60, 80.

- de Cauna, Jacques. 2004. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'indépendance d'Haïti: Témoignages pour une commémoration. Paris: Ed. Karthala.

- Bell, p. 61; James, p. 104

- Parkinson, Wenda. 1978. 'This Gilded African': Toussaint L'Ouverture . Quartet Books. p. 37.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 24–25.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 62.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 76.

- Cauna, pp. 63–65

- Bell, pp. 72–73

- Meade, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 68. ISBN 978-1118772485.

- Bell, pp. 12–15; James, pp. 81–82

- James, p. 90; Bell, pp. 23–24

- Bell, pp. 32–33

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 33.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 34–35

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 42-50.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 46.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 28, 55.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 50.

- Langley, Lester (1996). The Americas in the Age of Revolution: 1750–1850. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 111.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 56.

- James, pp. 125–126

- Bell, pp. 86–87; James, p. 107

- David Geggus (ed.). Haitian Revolutionary Studies. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002, pp. 125–126.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 54.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 18.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 19.

- James, pp. 128–130

- James, p. 137

- James, pp. 141–142

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 92–95.

- Charles Forsdick and Christian Høgsbjerg. Toussaint Louverture: A Black Jacobin in the Age of Revolutions. London: Pluto Press, 2017, p. 55.

- Geggus (ed.). Haitian Revolutionary Studies. pp. 120–129.

- Geggus (ed.). Haitian Revolutionary Studies. p. 122.

- Geggus (ed.). Haitian Revolutionary Studies. pp. 122–123.

- Ada Ferrer. Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolutions, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 2014, pp. 117–118.

- Ferrer. Freedom's Mirror. p. 119

- James. The Black Jacobins. pp. 143–144.

- Beaubrun Ardouin. Études sur l'Histoire d'Haïti. Port-au-PrinceL Dalencour, 1958, pp. 2:86–93.

- Thomas Ott. The Haitian Revolution, 1789–1804. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1973, pp. 82–83.

- Geggus (ed.). Haitian Revolutionary Studies. pp. 120–122.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 104–108.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 109.

- James, p. 143

- James, p. 147

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 115.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 110–114.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 113, 126.

- James, pp. 155–156

- James, pp. 152–154

- Laurent Dubois and John Garrigus, Slave Revolution in the Caribbean, 1789–1804: A Brief History with Documents. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 31

- Dubois and Garrigus, p. 31

- Bell, pp. 132–134; James, pp. 163–173

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 136.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 137, 140–141.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 147-148.

- Bell, p. 145, James, p. 180

- James, pp. 174–176; Bell, pp. 141–142, 147

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 145-146.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 150.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 150-153.

- James, p. 190; Bell, pp. 153–154

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 153.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 153, 155

- James, p. 179

- Bell (2008) [2007], p.155.

- Bell, pp. 142–143

- James, p. 201

- James, pp. 201–202

- James, pp. 202, 204

- James, pp. 207–208

- James, pp. 211–212

- Bell, pp. 159–160

- James, pp. 219–220

- Bell, pp. 165–166

- Bell, pp. 166–167

- Philippe Girard, "Black Talleyrand: Toussaint L'Ouverture's Secret Diplomacy with England and the United States", William and Mary Quarterly 66:1 (Jan. 2009), 87–124.

- Bell, pp. 173–174

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 174–175.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 175–177, 178–179.

- James, pp. 229–230

- James, pp. 224, 237

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 177.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 182–185.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 179–180.

- James, pp. 236–237

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 180

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 184.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 186

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 180–182, 187.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 189–191.

- Alexis, Stephen. Black Liberator. London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1949, p. 165

- "Constitution de la colonie français de Saint-Domingue", Le Cap, 1801

- Ogé, Jean-Louis. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'Indépendence d'Haïti. Brossard: L’Éditeur de Vos Rêves, 2002, p. 140

- Bell, pp. 210–211

- Ogé, Jean-Louis. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'Indépendence d'Haïti. Brossard: L’Éditeur de Vos Rêves, 2002, p. 141

- Philippe Girard, The Slaves Who Defeated Napoléon: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the Haitian War of Independence (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, November 2011).

- Latson, Jennifer (26 February 2015). "Why Napoleon Probably Should Have Just Stayed in Exile the First Time". Time. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- James, p. 263

- Philippe Girard, "Napoléon Bonaparte and the Emancipation Issue in Saint-Domingue, 1799–1803," French Historical Studies 32:4 (Fall 2009), 587–618.

- James, pp. 292–294; Bell, pp. 223–224

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 206–209, 226–229, 250

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 232–234

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 234–236.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 234, 236–237.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 256–260.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 237–241.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 261–262.

- Girard, Philippe R. (July 2012). "Jean-Jacques Dessalines and the Atlantic System: A Reappraisal" (PDF). The William and Mary Quarterly. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 69 (3): 559. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.69.3.0549. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

a list of “extraordinary expenses incurred by General Brunet in regards to [the arrest of] Toussaint” started with “gifts in wine and liquor, gifts to Dessalines and his spouse, money to his officers: 4000 francs.”

- Girard, Philippe R. (2011), The Slaves who Defeated Napoléon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence, 1801–1804, University of Alabama Press

- "Le rêve américain et caraïbe de Bonaparte : Le destin de la Louisiane française." L'expédition de Saint-Domingue, Napoleon.org

- Abbott, Elizabeth (1988). Haiti: An Insider's Hhistory of the Rise and Fall of the Duvaliers. Simon & Schuster. p. viii ISBN 0-671-68620-8

- John Bigelow: "The last days of Toussaint Louverture"

- Pike, Tim. "Toussaint Louverture: helping Bordeaux come to terms with its slave trade past" (part 1) ~ Invisible Bordeaux website

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 194.

- Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 56, 196.

- Bell (2008) [2007], p. 63.

- Clement XII, Pope. "In Eminenti". papalenciclicals.net. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Clavin, Matthew (2008). "A Second Haitian Revolution". Civil War History. liv (2).

- Yacou, Alain, ed. (2007). "Vie et mort du général Toussaint-Louverture selon les dossiers conservés au Service Historique de la Défense, Château de Vincennes". Saint-Domingue espagnol et la révolution nègre d'Haïti (in French). Karthala Editions. p. 346. ISBN 978-2811141516. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- le Cadet, Nicolas (21 October 2010). "Le portrait du juge idéal selon Noël du Fail dans les Contes et Discours d'Eutrapel". Centre d’Études et de Recherche Éditer/Interpréter (in French). University of Rouen. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Hutchins, Rachel D. (2016). Nationalism and History Education: Curricula and Textbooks in the United States and France. Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 978-1317625360. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "To Toussaint L'Ouverture" at ChickenBones: A Journal.

- Gardner, Eric (2001). "'A Gentleman of Superior Cultivation and Refinement': Recovering the Biography of Frank J. Webb". African American Review. 35 (2): 297–308. doi:10.2307/2903259. JSTOR 2903259.

- McLemee, Scott. 1996. "C.L.R. James: A Biographical Introduction." American Visions (April/May). mclemee.com

- Brewster, Yvonne. 7 September 2017. "Directing The Black Jacobins." British Library. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Alitashkgallery.com Archived 11 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Tracy, Steven C. (2004). A Historical Guide to Ralph Ellison. Oxford University Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0199727322. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Lydia Bailey at AllMovie

- Griffel, Margaret Ross (2012). Operas in English: A Dictionary. Scarecrow Press. p. 501. ISBN 978-0810883253. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Emmerling, Leonhard (2003). Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1960–1988. Taschen. p. 88. ISBN 978-3822816370. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Sepinwall, Alyssa Goldstein (13 October 2013). "Happy as a Slave: The Toussaint Louverture miniseries". Fiction and Film for French Historians. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

Works cited

- Alexis, Stephen. 1949. Black Liberator: The Life of Toussaint Louverture. London: Ernest Benn.

- Ardouin, Beaubrun. 1958. Études sur l'Histoire d'Haïti. Port-au-Prince: Dalencour.

- Beard, John Relly. 1853. The Life of Toussaint L'Ouverture: The Negro Patriot of Hayti. ISBN 1-58742-010-4

- — [1863] 2001. Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography (online ed.). Boston: James Redpath. — Consists of the earlier "Life", supplemented by an autobiography of Toussaint written by himself.

- Bell, Madison Smartt (2008) [2007]. Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1400079353.

- de Cauna, Jacques. 2004. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'indépendance d'Haïti. Témoignages pour une commémoration. Paris: Ed. Karthala.

- Cesaire, Aimé. 1981. Toussaint L'Ouverture. Paris: Présence Africaine. ISBN 2-7087-0397-8.

- Davis, David Brion. 31 May 2007. "He changed the New World." The New York Review of Books. pp. 54–58. — Review of M. S. Bell's Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography.

- Dubois, Laurent, and John D. Garrigus. 2006. Slave Revolution in the Caribbean, 1789–1804: A Brief History with Documents. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-41501-X.

- DuPuy, Alex. 1989. Haiti in the World Economy: Class, Race, and Underdevelopment since 1700. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-7348-4.

- Ferrer, Ada. 2014. Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107697782

- Foix, Alain. 2007. Toussaint L'Ouverture. Paris: Ed. Gallimard.

- — 2008. Noir de Toussaint L'Ouverture à Barack Obama. Paris: Ed. Galaade.

- Forsdick, Charles, and Christian Høgsbjerg, eds. 2017. The Black Jacobins Reader. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- — 2017. Toussaint Louverture: A Black Jacobin in the Age of Revolutions. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745335148.

- Geggus, David, ed. 2002. Haitian Revolutionary Studies. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253341044.

- Girard, Philippe. 2009. "Black Talleyrand: Toussaint L'Ouverture’s Secret Diplomacy with England and the United States." William and Mary Quarterly 66(1):87–124.

- — 2009. "Napoléon Bonaparte and the Emancipation Issue in Saint-Domingue, 1799–1803." French Historical Studies 32(4):587–618.

- — 2011. The Slaves who Defeated Napoléon: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the Haitian War of Independence, 1801–1804. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817317325.

- — 2012. "Jean-Jacques Dessalines and the Atlantic System: A Reappraisal." William and Mary Quarterly.

- — 2016. Toussaint Louverture: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Basic Books.

- Graham, Harry. 1913. "The Napoleon of San Domingo", The Dublin Review 153:87–110.

- Heinl, Robert, and Nancy Heinl. 1978. Written in Blood: The story of the Haitian people, 1492–1971. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-26305-0.

- Hunt, Alfred N. 1988. Haiti's Influence on Antebellum America: Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-3197-0.

- James, C. L. R. [1934] 2013. Toussaint L'Ouverture: The story of the only successful slave revolt in history: A Play in Three Acts. Duke University Press.

- — [1963] 2001. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-029981-5.

- Johnson, Ronald Angelo. 2014. Diplomacy in Black and White: John Adams, Toussaint Louverture, and Their Atlantic World Alliance. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Joseph, Celucien L. 2012. Race, Religion, and The Haitian Revolution: Essays on Faith, Freedom, and Decolonization. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- — 2013. From Toussaint to Price-Mars: Rhetoric, Race, and Religion in Haitian Thought. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Korngold, Ralph. [1944] 1979. Citizen Toussaint. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-20794-1.

- de Lacroix, F. J. Pamphile. [1819] 1995. La révolution d'Haïti.

- Norton, Graham Gendall. April 2003. "Toussaint L'Ouverture." History Today.

- Ott, Thomas. 1973. The Haitian Revolution: 1789–1804. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-545-3

- Parkinson, Wenda. 1978. 'This Gilded African': Toussaint L'Ouverture. Quartet Books.

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. 2006. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-33271-1.

- Ros, Martin. [1991] 1994. The Night of Fire: The Black Napoleon and the Battle for Haiti (in Dutch). New York; Sarpedon. ISBN 0-9627613-7-0.

- Schlesinger Jr., Arthur M. World leaders, past & present – Toussaint L'ouverture.

- Schoelcher, Victor. 1889. Vie de Toussaint-L'Ouverture.

- Stinchcombe, Arthur L. 1995. Sugar Island Slavery in the Age of Enlightenment: The Political Economy of the Caribbean World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-0777-8

- The Collective Works of Yves. ISBN 1-4010-8308-0

- Book I explains Haiti's past to be recognized.

- Book 2 culminates Haiti's scared present day epic history.

- Thomson, Ian. 1992. Bonjour Blanc: A Journey Through Haiti. London. ISBN 0-09-945215-4.

- L'Ouverture, Toussaint. 2008. The Haitian Revolution, with an introduction by J. Aristide. New York: Verso. — A collection of L'Ouverture's writings and speeches. ISBN 1-84467-261-1.

- Tyson, George F., ed. 1973. Great Lives Considered: Toussaint L'Ouverture. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-925529-X. — A compilation, includes some of Toussaint's writings.

Further reading

Primary sources

- "Letters of Toussaint Louverture and of Edward Stevens, 1798-1800". The American Historical Review. 16 (1): 64–101. October 1910. JSTOR 1834309.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toussaint Louverture. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Toussaint Louverture |

- Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography by J. R. Beard, 1863

- A section of Bob Corbett's on-line course on the history of Haïti that deals with Toussaint's rise to power.

- The Louverture Project

- Toussaint on IMDb

- "Égalité for All: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution". Noland Walker. PBS documentary. 2009.

- Spencer Napoleonica Collection at Newberry Library

- Black Spartacus by Anthony Maddalena (Thee Black Swan Theatre Company); a radio play in four parts which tells the story of Toussaint L'Ouverture and the Haitian Slave Uprising of 1791–1803

- Paul Foot on Toussaint Louverture (lecture from 1991)

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1889.

- Elliott, Charles Wyllys. St. Domingo, its revolution and its hero, Toussaint Louverture, New York, J. A. Dix, 1855. Manioc

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Toussaint L'Ouverture by Wendell Phillips (hardcover edition, published in English, French and Kreyòl Ayisyen).