To Live (1994 film)

To Live, also titled Lifetimes in some English versions,[1] is a Chinese drama film directed by Zhang Yimou in 1994, starring Ge You, Gong Li, and produced by the Shanghai Film Studio and ERA International. It is based on the novel of the same name by Yu Hua. Having achieved international success with his previous films (Ju Dou and Raise the Red Lantern), director Zhang Yimou's To Live came with high expectations. It is the first Chinese film that had its foreign distribution rights pre-sold.[2]

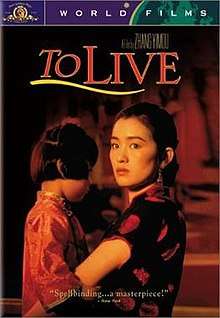

| To Live | |

|---|---|

To Live DVD cover | |

| Traditional | 活著 |

| Simplified | 活着 |

| Mandarin | Huózhe |

| Literally | alive / to be alive |

| Directed by | Zhang Yimou |

| Produced by | Chiu Fu-sheng Funhong Kow Christophe Tseng |

| Written by | Lu Wei |

| Based on | To Live by Yu Hua |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Zhao Jiping |

| Cinematography | Lü Yue |

| Edited by | Du Yuan |

| Distributed by | The Samuel Goldwyn Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 132 minutes |

| Country | China |

| Language | Mandarin |

| Box office | $32900 |

The film was denied a theatrical release in mainland China by the Chinese State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television[3] due to its critical portrayal of various policies and campaigns of the Communist government.

To Live was screened at the 1994 New York Film Festival before eventually receiving a limited release in the United States on November 18, 1994.[4] The film has been used in the United States as a support to teach Chinese history in high schools and colleges.[5]

The film applies chronological narration to address the social practices of China’s ideology, the difficulty of Chinese staying alive reflects how the government controls the nation as a collective community without considering individuals' profits.[6]

The portrayal of Chinese living under social pressures create the meaning of the film, people’s grinding experience shows they have resistance and struggles under political changes.[6]

Development

Zhang Yimou originally intended to adapt Mistake at River's Edge, a thriller written by Yu Hua. Yu gave Zhang a set of all of the works that had been published at that point so Zhang could understand his works. Zhang said that he began reading To Live, one of the works, and was unable to stop reading it. Zhang met Yu to discuss the script for Mistake at River's Edge, but they kept bringing up To Live. The two decided to have To Live adapted instead.[1]

Plot

In the 1940s, Xu Fugui (Ge You) is a rich man's son and compulsive gambler, who loses his family property to a man named Long'er. His behavior also causes his long-suffering wife Jiazhen (Gong Li) to leave him, along with their daughter, Fengxia, and their unborn son, Youqing.

Fugui eventually reunites with his wife and children but is forced to start a shadow puppet troupe with a partner named Chunsheng. The Chinese Civil War is occurring at the time, and both Fugui and Chunsheng are conscripted into the Kuomintang's Republic of China armed forces during a performance. Midway through the war, the two are captured by the communist People's Liberation Army and serve by performing their shadow puppet routine for the communist revolutionaries. Eventually, Fugui is able to return home, only to find out that due to a week-long fever, Fengxia has become mute and partially deaf.

Soon after his return, Fugui learns that Long'er did not want to donate any of his wealth to the communist "people's government", preferring instead to burn all of his property. No one helps put out the fire because Long'er was a gentry. He is eventually put on trial and is sentenced to execution. As Long'er is pulled away, he recognizes Fugui in the crowd and tries to talk to him as he is dragged towards the execution grounds. Fugui is filled with fear and runs into an alleyway before hearing five gunshots. He runs home to tell Jiazhen what has happened, and they quickly pull out the certificate stating that Fugui served in the communist People's Liberation Army. Jiazhen assures him that they are no longer gentries and will not be killed.

The story moves forward a decade into the future, to the time of the Great Leap Forward. The local town chief enlists everyone to donate all scrap iron to the national drive to produce steel and make weaponry for retaking Taiwan. As an entertainer, Fugui performs for the entire town nightly, and is very smug about his singing abilities.

Soon after, some boys begin picking on Fengxia. Youqing decides to get back at one of the boys by dumping spicy noodles on his head during a communal lunch. Fugui is furious, but Jiazhen stops him and tells him why Youqing acted the way he did. Fugui realizes the love his children have for each other.

The children are exhausted from the hard labor they are doing in the town and try to sleep whenever they can. They eventually get a break during the festivities for meeting the scrap metal quota. The entire village eats dumplings in celebration. In the midst of the family eating, schoolmates of Youqing call for him to come prepare for the District Chief. Jiazhen tries to make Fugui let him sleep but eventually relents and packs her son twenty dumplings for lunch. Fugui carries his son to the school, and tells him to heat the dumplings before eating them, as he will get sick if he eats cold dumplings. He must listen to his father to have a good life.

Later on in the day, the older men and students rush to tell Fugui that his son has been killed by the District Chief. He was sleeping on the other side of a wall that the Chief's Jeep was on, and the car ran into the wall, injuring the Chief and crushing Youqing. Jiazhen, in hysterics, is forbidden to see her son's dead body, and Fugui screams at his son to wake up. Fengxia is silent in the background.

The District Chief visits the family at the grave, only to be revealed as Chunsheng. His attempts to apologize and compensate the family are rejected, particularly by Jiazhen, who tells him he owes her family a life. He returns to his Jeep in a haze, only to see his guard beating Fengxia for breaking the Jeep's windows. He tells him to stop, and walks home.

The story moves forward again another decade, to the Cultural Revolution. The village chief advises Fugui's family to burn their puppet drama props, which have been deemed as counter-revolutionary. Fengxia carries out the act, and is oblivious to the Chief's real reason for coming: to discuss a suitor for her. Fengxia is now grown up and her family arranges for her to meet Wan Erxi, a local leader of the Red Guards. Erxi, a man crippled by a workplace accident, fixes her parent's roof and paints depictions of Mao Zedong on their walls with his workmates. He proves to be a kind, gentle man; he and Fengxia fall in love and marry, and she soon becomes pregnant.

Chunsheng, still in the government, visits immediately after the wedding to ask for Jiazhen's forgiveness, but she refuses to acknowledge him. Later, he is branded a reactionary and a capitalist. He comes to tell them his wife has committed suicide and he intends to as well. He has come to give them all his money. Fugui refuses to take it. However, as Chunsheng leaves, Jiazhen commands him to live, reminding him that he still owes them a life.

Months later, during Fengxia's childbirth, her parents and husband accompany her to the county hospital. All doctors have been sent to do hard labor for being over educated, and the students are left as the only ones in charge. Wan Erxi manages to find a doctor to oversee the birth, removing him from confinement, but he is very weak from starvation. Fugui purchases seven steamed buns (mantou) for him and the family decides to name the son Mantou, after the buns. However, Fengxia begins to hemorrhage, and the nurses panic, admitting that they do not know what to do. The family and nurses seek the advice of the doctor, but find that he has overeaten and is semiconscious. The family is helpless, and Fengxia dies from postpartum hemorrhage (severe blood loss). The point is made that the doctor ate 7 buns, but that by drinking too much water at the same time, each bun expanded to the size of 7 buns: therefore Fengxia's death is a result of the doctor's having the equivalent of 49 buns in his belly.

The movie ends six years later, with the family now consisting of Fugui, Jiazhen, their son-in-law Erxi, and grandson Mantou. The family visits the graves of Youqing and Fengxia, where Jiazhen, as per tradition, leaves dumplings for her son. Erxi buys a box full of young chicks for his son, which they decide to keep in the chest formerly used for the shadow puppet props. When Mantou inquires how long it will take for the chicks to grow up, Fugui's response is a more tempered version of something he said earlier in the film. However, in spite of all of his personal hardships, he expresses optimism for his grandson's future, and the film ends with his statement, "and life will get better and better" as the whole family sits down to eat.[7] Although the ending has been criticized as sentimental, the resignation and forced good cheer of Fugui and especially Jiazhen belie a happy ending.[8]

Cast

- Ge You as Xu Fugui (t 徐福貴, s 徐福贵, Xú Fúguì, lit. "Lucky & Rich")

- Gong Li as Jiazhen (家珍, Jiāzhēn, lit. "Precious Family"), his wife

- Liu Tianchi as adult Xu Fengxia (t 徐鳳霞, s 徐凤霞, Xú Fèngxiá, lit. "Phoenix & Rosy Clouds"), his daughter

- Xiao Cong as teenage Xu Fengxia

- Zhang Lu as child Xu Fengxia

- Fei Deng as Xu Youqing (t 徐有慶, s 徐有庆, Xú Yǒuqìng, lit. "Full of Celebration"), his son

- Jiang Wu as Wan Erxi (t 萬二喜, s 万二喜, Wàn Èrxǐ, lit. "Double Happiness"), Fengxia's husband

- Ni Dahong as Long'er (t 龍二, s 龙二, Lóng'èr lit. "Dragon the Second")

- Guo Tao as Chunsheng (春生, Chūnshēng, lit. "Spring-born")

Year-end lists

- 4th – Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times[9]

- 5th – Janet Maslin, The New York Times[10]

- 5th – James Berardinelli, ReelViews[11]

- 9th – Michael MacCambridge, Austin American-Statesman[12]

- Honorable mention – Mike Clark, USA Today[13]

- Honorable mention – Betsy Pickle, Knoxville News-Sentinel[14]

Awards and nominations

| Awards | Year | Category | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannes Film Festival[15] | 1994 | Grand Prix | Won | with Burnt by the Sun |

| Prize of the Ecumenical Jury | Won | with Burnt by the Sun | ||

| Best Actor (Ge You) |

Won | |||

| Palme d'Or | Nominated | |||

| Golden Globe Award[16] | 1994 | Best Foreign Language Film | Nominated | |

| National Board of Review[17] | 1994 | Best Foreign Language Film | Top 5 | with four other films |

| National Society of Film Critics Award[18] | 1995 | Best Foreign Language Film | Runner-up | |

| BAFTA Award[19] | 1995 | Best Film Not in the English Language | Won | |

| Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association Award[18] | 1995 | Best Foreign Film | Runner-up |

- Accolades

Differences from the novel

- The film changes the setting from rural southern China to a small city in northern China. The film added the element of Fugui's shadow puppetry. The second narrator and the ox are not present in the film. Additionally, Fugui has a sense of political idealism that is not present in the original novel. By the end of the film he loses this sense of idealism.[1]

- The novel written by Yu Hua is a retrospective. In contrast with Yu Hua’s literary style, Zhang adapts the film without the remembrance tone.[6]

- The major change introduced by Zhang is the elimination of Yu Hua's first-person narration.[6]

- Fugui is the only survivor of his family in the novel, but in Zhang’s film there are four members of the family who survive.[6]

Symbols in the film

Food

- Dumplings: Youqing’s lunch box was never opened even if he dies; the dumplings set on Youqing’s tomb on Youqing’s funeral as well as the end of the film when they visit Youqing and Fengxia’s tomb. The dumplings, rather than being eaten and absorbed, the lumps of dough and meat now stand as reminders of a life that has been irreparably wasted.[6]

- Mantou (Steamed wheat bun): When Fengxia is giving birth, the only profession doctor Professor Wang is almost chok by the buns hence Wang cannot be able to save Fengxia’s life. The mantou, meant to ease Professor Wang's hunger so that he can assist in the childbirth, rehydrate and expand within his starvation-shrunken stomach. “Filling stomach” ironically leads to the death of Fengxia. The buns (foods) are not supportive to survive in this case, it is the indirect killer of Fengxia.[6]

- Noodles: Youqing does not view food as the most important, as he uses his meal for revenge. Again, the noodles are not being eaten and wasted for Youqing’s revenge in order to protect his sister. Noodles are wasted literally thus not wasted in Youqing’s mind. Food is not merely for “filling stomach” or “to live”. On the other hands, “to live” is not depend solely on foods.[6]

Shadow puppetry

The usage of shadow puppetry, which carries a historical and cultural heritage, throughout the movie acts as a parallel to what characters experience in the events that they have to live through.[23]

Scripts in the film

The little chickens will grow to be ducks, the ducks will become geese, and the geese will become oxen, and tomorrow will be better. (In the early version, “tomorrow will be better” because of communism, as he told this story of transformation to his son, who was sleeping on his shoulder on the way to his school one day in the Great Leap Forward period.)

This script and the ending scene acts as a picture of perseverance of the Chinese people in the face of historical hardships, giving the feeling of hope to the contemporary audience.[6]

Facts in the film

- The fear of ostracization means that the process of socialization-of learning to live with others-is one of punishment and discipline.[6]

- Fugui's act shows implicitly patriarchal attitude toward the community.[6]

- Referential meaning of the film: The scene in which the father publicly punishes the son in To Live can be read as a miniaturized re-rendering of that dramatic punishing scene watched by the entire world in June 1989 -- Tiananmen Massacre.[6]

Chinese censorship

The ability of people to watch To Live, which was a banned movie, shows the inefficiency of the censorship system put in place in China at the time.[23]

See also

- Banned films in China

- Censorship in the People's Republic of China

- List of Chinese films

- List of films featuring the deaf and hard of hearing

Notes

- Yu, Hua. Editor: Michael Berry. To Live. Random House Digital, Inc., 2003. 242. ISBN 978-1-4000-3186-3.

- Klapwald, Thea (1994-04-27). "On the Set with Zhang Yimou". The International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 2012-09-18. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- Zhang Yimou. Frances K. Gateward, Yimou Zhang, University Press of Mississippi, 2001, pp. 63-4.

- James, Caryn (1994-11-18). "Film Review; Zhang Yimou's 'To Live'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- Amy Mungur, “Chinese Movies and History Education: The Case of Zhang Yimou's 'To Live',” History Compass 9,7 (2011): 518–524.

- Chow, Rey (1996). "We Endure, Therefore We Are: Survival, Governance, and Zhang Yimou's To Live". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0110081/synopsis

- Larson, Wendy (2017). Zhang Yimou: Globalization and the Subjection of Culture. Amherst, New York: Cambria Press. pp. 167–196. ISBN 9781604979756.

- Turan, Kenneth (December 25, 1994). "1994: YEAR IN REVIEW : No Weddings, No Lions, No Gumps". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- Maslin, Janet (December 27, 1994). "CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK; The Good, Bad and In-Between In a Year of Surprises on Film". The New York Times. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Berardinelli, James (January 2, 1995). "Rewinding 1994 -- The Year in Film". ReelViews. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- MacCambridge, Michael (December 22, 1994). "it's a LOVE-HATE thing". Austin American-Statesman (Final ed.). p. 38.

- Clark, Mike (December 28, 1994). "Scoring with true life, `True Lies' and `Fiction.'". USA Today (Final ed.). p. 5D.

- Pickle, Betsy (December 30, 1994). "Searching for the Top 10... Whenever They May Be". Knoxville News-Sentinel. p. 3.

- "Festival de Cannes – Huozhe". Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011.

- "Winners & Nominees 1994". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016.

- "1994 Archives". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- "Huo zhe – Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- "BAFTA Awards (1995)". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- "100 best Chinese Mainland Films (top 10)". Time Out. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- Mackay, Mairi (23 September 2008). "Pick the best Asian films of all time". CNN. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- Lu, Sheldon H. (1997). Transnational Chinese Cinemas. University of Hawai'i Press.

Further reading

- Giskin, Howard and Bettye S. Walsh. An Introduction to Chinese Culture Through the Family. SUNY Press, 2001. ISBN 0-7914-5048-1, ISBN 978-0-7914-5048-2.

- Xiao, Zhiwei. "Reviewed work(s): The Wooden Man's Bride by Ying-Hsiang Wang; Yu Shi; Li Xudong; Huang Jianxin; Yang Zhengguang Farewell My Concubine by Feng Hsu; Chen Kaige; Lillian Lee; Wei Lu The Blue Kite by Tian Zhuangzhuang To Live by Zhang Yimou; Yu Hua; Wei Lu; Fusheng Chin; Funhong Kow; Christophe Tseng." The American Historical Review. Vol. 100, No. 4 (Oct. 1995), pp. 1212–1215

- Chow, Rey. "We Endure, Therefore We Are: Survival, Governance, and Zhang Yimou's To Live." South Atlantic Quarterly 95 (1996): 1039-1064.

- Shi, Liang. "The Daoist Cosmic Discourse in Zhang Yimou's "to Live"."] Film Criticism, vol. 24, no. 2, 1999, pp. 2-16.

External links

- To Live on IMDb

- To Live at AllMovie

- To Live at Rotten Tomatoes

- To Live at Box Office Mojo