The Planets

The Planets, Op. 32, is a seven-movement orchestral suite by the English composer Gustav Holst, written between 1914 and 1916. Each movement of the suite is named after a planet of the solar system and its corresponding astrological character as defined by Holst.

| The Planets | |

|---|---|

| Orchestral suite by Gustav Holst | |

First UK edition | |

| Opus | 32 |

| Based on | Planets in astrology |

| Composed | 1914–16 |

| Movements | seven |

| Scoring | Orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 29 September 1918 |

| Location | Queen's Hall, London |

| Conductor | Adrian Boult |

From its premiere to the present day, the suite has been enduringly popular, influential, widely performed and frequently recorded. The work was not heard in a complete public performance, however, until some years after it was completed. Although there were four performances between September 1918 and October 1920, they were all either private (the first performance, in London) or incomplete (two others in London and one in Birmingham). The premiere was at the Queen's Hall on 29 September 1918,[1] conducted by Holst's friend Adrian Boult before an invited audience of about 250 people. The first complete public performance was finally given in London by Albert Coates conducting the London Symphony Orchestra on 15 November 1920.[2]

Background

The concept of the work is astrological[3] rather than astronomical (which is why Earth is not included, although Sun and Moon are also not included while including the non-traditional Uranus and Neptune): each movement is intended to convey ideas and emotions associated with the influence of the planets on the psyche, not the Roman deities. The idea of the work was suggested to Holst by Clifford Bax, who introduced him to astrology when the two were part of a small group of English artists holidaying in Majorca in the spring of 1913; Holst became quite a devotee of the subject, and would cast his friends' horoscopes for fun.[3][4] Holst also used Alan Leo's[3] book What is a Horoscope? as a springboard for his own ideas, as well as for the subtitles (e.g., "The Bringer of...") for the movements.

On 17 January 1914 Holst attended a performance of Arnold Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra, at the Queen's Hall, conducted by Schoenberg's pupil Edward Clark.[5][6][7] Holst quickly acquired a copy of the score, the only Schoenberg score he ever owned. This influenced Holst at least to the degree that the working title of his own composition was Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra.[8]

When composing The Planets Holst initially scored the work for four hands, two pianos, except for Neptune, which was scored for a single organ, as Holst believed that the sound of the piano was too percussive for a world as mysterious and distant as Neptune. Holst then scored the suite for a large orchestra, in which form it became enormously popular. Holst's use of orchestration was very imaginative and colourful, showing the influence of such contemporary composers as Igor Stravinsky[9] and Arnold Schoenberg,[3] as well as such late Russian romantics as Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov. Its novel sonorities helped make the work an immediate success with audiences at home and abroad. Although The Planets remains Holst's most popular work, the composer himself did not count it among his best creations and later in life complained that its popularity had completely surpassed his other works. He was, however, partial to his own favourite movement, Saturn.[10]

Premieres

Adrian Boult[11]

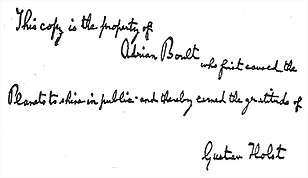

The orchestral premiere of The Planets suite, conducted at Holst's request by Adrian Boult, was held at short notice on 29 September 1918, during the last weeks of World War I, in the Queen's Hall with the financial support of Holst's friend and fellow composer H. Balfour Gardiner. It was hastily rehearsed; the musicians of the Queen's Hall Orchestra first saw the complicated music only two hours before the performance, and the choir for Neptune was recruited from pupils from Morley College and St Paul's Girls' School (where Holst taught). It was a comparatively intimate affair, attended by around 250 invited associates,[4][12][13] but Holst regarded it as the public premiere, inscribing Boult's copy of the score, "This copy is the property of Adrian Boult who first caused the Planets to shine in public and thereby earned the gratitude of Gustav Holst."[11]

A public concert was given in London under the auspices of the Royal Philharmonic Society on 27 February 1919, conducted by Boult. Five of the seven movements were played in the order Mars, Mercury, Saturn, Uranus, and Jupiter.[14][15] It was Boult's decision not to play all seven movements at this concert. He felt that when the public were being given a totally new language like that, "half an hour of it was as much as they could take in".[16] The anonymous critic in Hazell's Annual called it "an extraordinarily complex and clever suite".[17] At a Queen's Hall symphony concert on 22 November of that year, Holst conducted Venus, Mercury and Jupiter (this was the first public performance of Venus).[15][18] There was another incomplete public performance, in Birmingham, on 10 October 1920, with five movements (Mars, Venus, Mercury, Saturn and Jupiter). It is not clear whether this performance was conducted by Appleby Matthews[19] or the composer.[20]

His daughter Imogen recalled, "He hated incomplete performances of The Planets, though on several occasions he had to agree to conduct three or four movements at Queen's Hall concerts. He particularly disliked having to finish with Jupiter, to make a 'happy ending', for, as he himself said, 'in the real world the end is not happy at all'".[21]

The first complete performance of the suite at a public concert did not occur until 15 November 1920; the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) was conducted by Albert Coates. This was the first time the movement Neptune had been heard in a public performance, all the other movements having been given earlier public airings.[2]

The composer conducted a complete performance for the first time on 13 October 1923, with the Queen's Hall Orchestra at a Promenade Concert. Holst conducted the LSO in two recorded performances of The Planets: the first was an acoustic recording made in sessions between 1922 and 1924 (now available on Pavilion Records' Pearl label); the second was made in 1926, and utilised the then-new electrical recording process (in 2003, this was released on compact disc by IMP and later on Naxos outside the United States).[22] Because of the time constraints of the 78rpm format, the tempo is often much faster than is usually the case today.[23]

Instrumentation

The work is scored for a large orchestra consisting of the following instrumentation. The movements vary in the combinations of instruments used.

|

|

|

In "Neptune", two three-part women's choruses (each comprising two soprano sections and one alto section) located in an adjoining room which is to be screened from the audience are added.

Structure

The suite has seven movements, each named after a planet and its corresponding astrological character (see Planets in astrology):

- Mars, the Bringer of War (1914)

- Venus, the Bringer of Peace (1914)

- Mercury, the Winged Messenger (1916)

- Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity (1914)

- Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age (1915)

- Uranus, the Magician (1915)

- Neptune, the Mystic (1915)

Holst's original title, as seen on the handwritten full score, was "Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra".[25] Holst almost certainly attended an early performance of Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra in 1914 (the year he wrote Mars, Venus and Jupiter),[n 1] and owned a score of it,[27][28] the only Schoenberg score he ever owned.[25] Each movement of Holst's work was originally called only by the second part of each title (I "The Bringer of War", II "The Bringer of Peace" and so on); the present titles were added in time for the first (incomplete) public performance in September 1918, though they were never added to the original score.[27]

A typical performance of all seven movements is about fifty minutes long, though Holst's own electric recording from 1926 is just over forty-two and a half minutes.[29]

One explanation for the suite's structure, presented by Holst scholar Raymond Head, is the ruling of astrological signs of the zodiac by the planets:[30] if the signs are listed along with their ruling planets in the traditional order starting with Aries, ignoring duplication and the luminaries (the Sun and Moon), the order of the movements corresponds. Critic David Hurwitz offers an alternative explanation for the piece's structure: that Jupiter is the centrepoint of the suite and that the movements on either side are in mirror images. Thus Mars involves motion and Neptune is static; Venus is sublime while Uranus is vulgar, and Mercury is light and scherzando while Saturn is heavy and plodding. This hypothesis is lent credence by the fact that the two outer movements, Mars and Neptune, are both written in rather unusual quintuple meter.

Holst suffered neuritis in his right arm, which caused him to seek help from Vally Lasker and Nora Day, two amanuenses, in scoring The Planets.[27][31]

Neptune was one of the first pieces of orchestral music to have a fade-out ending,[32] although several composers (including Joseph Haydn in the finale of his Farewell Symphony) had achieved a similar effect by different means. Holst stipulates that the women's choruses are "to be placed in an adjoining room, the door of which is to be left open until the last bar of the piece, when it is to be slowly and silently closed", and that the final bar (scored for choruses alone) is "to be repeated until the sound is lost in the distance".[33] Although commonplace today, the effect bewitched audiences in the era before widespread recorded sound—after the initial 1918 run-through, Holst's daughter Imogen (in addition to watching the charwomen dancing in the aisles during Jupiter) remarked that the ending was "unforgettable, with its hidden chorus of women's voices growing fainter and fainter... until the imagination knew no difference between sound and silence".[4]

Additions by other composers

Several attempts have been made, for a variety of reasons, to append further music to Holst's suite, though by far the most common presentation of the music in the concert hall and on record remains Holst's original seven-movement version.[34][35][36][37][38]

Pluto

Pluto was discovered in 1930, four years before Holst's death, and was hailed by astronomers as the ninth planet. Holst, however, expressed no interest in writing a movement for the new planet. He had become disillusioned by the popularity of the suite, believing that it took too much attention away from his other works.[39]

In the final broadcast of his Young People's Concerts series in March 1972, the conductor Leonard Bernstein led the New York Philharmonic through a fairly straight interpretation of the suite, though he discarded the Saturn movement because he thought the theme of old age was irrelevant to a concert for children. The broadcast concluded with an improvised performance he called "Pluto, the Unpredictable".[40] The performance may be viewed on the Kultur DVD set.

In 2000, the Hallé Orchestra commissioned the English composer Colin Matthews, an authority on Holst, to write a new eighth movement, which he called "Pluto, the Renewer". Dedicated to the late Imogen Holst, Gustav Holst's daughter, it was first performed in Manchester on 11 May 2000, with Kent Nagano conducting the Hallé Orchestra. Matthews also changed the ending of Neptune slightly so that movement would lead directly into Pluto.[41] Matthews himself has speculated that, the dedication notwithstanding, Imogen Holst "would have been both amused and dismayed by the venture."[42]

Earth, from The Planets by Trouvère

Japanese composer Jun Nagao arranged The Planets for the Trouvère Quartet in 2003, including added movements for Earth and Pluto, since the latter was considered a planet at the time. The suite was arranged for concert band and premiered in 2014. The work contains original themes, themes from The Planets, and other popular Holst melodies.[43]

Recordings

Adaptations

Non-orchestral arrangements

- Piano duet (four hands) – an engraved copy of Holst's own piano duet arrangement was found by John York.[44]

- Two pianos (duo) – Holst had originally sketched the work for two pianos, due to a need to compensate for the neuritis in his right arm. His two friends, Nora Day and Vally Lasker, had agreed to play the two-piano arrangement for him as he dictated the details of the orchestral score to them. This they wrote down themselves on the two-piano score, and used as a guide when it was time to create the full orchestral score.[45] The two-piano arrangement was published in 1949. Holst's original manuscripts for it are now in the holdings of the Royal College of Music (Mars, Venus, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune), Royal Academy of Music (Mercury) and British Library (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus).[46]

- Pianola – In the early 1990s an arrangement was made for piano rolls by the English pianolist, Rex Lawson, and published on the Perforetur label.[47]

- Organ – American harpsichordist and organist Peter Sykes transcribed The Planets for organ.[48][49]

- Ensemble or Chamber Orchestra – English orchestrator George Morton transcribed The Planets for 15-piece ensemble or chamber orchestra.[50][51]

- Moog – Isao Tomita adapted The Planets for a Moog and other synthesizers and electronic devices.[52] The original LP release prompted legal action from Holst's estate. The composer's daughter, Imogen Holst, worked hard to prevent the recording being distributed in the UK.[53] Patrick Gleeson also recorded an electronic version in 1976 called Beyond the Sun.

- Brass instruments – Hungarian trombonist and arranger Áron Simon transcribed the Mars movement for 6 trombones, euphonium, tuba, timpani and percussion.[54]

- Brass band – Stephen Roberts, associate conductor of the English Symphony Orchestra, transcribed the entire suite for brass band.[55]

- Marching band – the movements Mars, Venus and Jupiter have all been arranged for marching band by Jay Bocook.[56] Paul Murtha also arranged the chorale section of Jupiter for marching band.,[57] Kevin Shah and Tony Nunez created a work on Jupiter entitled "Bringer of Joy" as well Project Rise Music » Marching Band

- Concert band – there are numerous transcriptions of the whole Suite for concert band.

- Percussion ensemble – James Ancona arranged Mercury for a percussion ensemble. It consisted of 2 glockenspiels, 2 xylophones, 2 vibraphones, 2 marimbas, 5 timpani, a small suspended cymbal, and 2 triangles.[58]

- Drum corps – selections from The Planets were performed by The Cavaliers as part of their 1985 repertoire, and as the entirety of their 1995 feature field show, as well as appearing in their 2017 production "Men Are From Mars".[59] A similar performance was recorded for CD by Star of Indiana as part of their Brass Theater series.

- Rock bands:

- King Crimson performed a rock arrangement of "Mars" at their live shows in 1969.[60] The band intended to make a studio recording of "Mars" for their second album, In the Wake of Poseidon, in 1970. However, this plan was met with resistance from Holst's estate, and the band instead composed a new piece of similar structure, "The Devil's Triangle," for the album.

- Emerson, Lake & Powell, whose bassist Greg Lake had been a member of King Crimson during 1969–70, recorded a version of "Mars" for their eponymous studio album in 1986.

- Death metal band Aeon recorded a version of "Neptune, the Mystic" for their album Aeons Black. Though much shorter than the original it was derived from a select few of the main melodies [61]

- British Metal bands: the introduction to Diamond Head's "Am I Evil?", as well as the main riff from "Black Sabbath" and the bridge from "Children of the Grave" by Black Sabbath, are loosely based on "Mars."[62][63] On their 1990 tour promoting the album Tyr parts of "Mars" are used as playback during Cozy Powell's drum solo.[64][65] Saxon used parts of "Jupiter" as a taped intro to their gigs in the late 1980s.[66]

- Japanese singer Ayaka Hirahara released a pop version of "Jupiter" in December 2003. It went to No. 2 on the Oricon charts and sold nearly a million copies, making it the third-best-selling single in the Japanese popular music market for 2004. It remained on the charts for over three years.[67]

Hymns

Holst adapted the melody of the central section of Jupiter in 1921 to fit the metre of a poem beginning "I Vow to Thee, My Country". As a hymn tune it has the title Thaxted, after the town in Essex where Holst lived for many years, and it has also been used for other hymns, such as "O God beyond all praising"[68] and "We Praise You and Acknowledge You" with lyrics by Rev. Stephen P. Starke.[69]

"I Vow to Thee, My Country" was written between 1908 and 1918 by Sir Cecil Spring Rice and became known as a response to the human cost of World War I. The hymn was first performed in 1925 and quickly became a patriotic anthem. Although Holst had no such patriotic intentions when he originally composed the music, these adaptations have encouraged others to draw upon the score in similar ways throughout the 20th century.

The melody was also adapted and set to lyrics by Charlie Skarbek and titled "World in Union".[70] The song is used as the theme song for the Rugby World Cup and appears in most television coverage and before matches.[70]

In popular culture

- Bell's Brewery claims that the suite served as an inspiration for its "The Planets Series" of beers.[71]

- Robert A. Heinlein references Mars in his novel Stranger in a Strange Land, used to establish Valentine Michael Smith's credentials when meeting the president.[72]

- Bill Conti was strongly influenced by Neptune and Jupiter in his soundtrack for the 1983 film The Right Stuff.[73]

- King Crimson's song "The Devil’s Triangle" from In the Wake of Poseidon was adapted from Mars.[74]

- BoJack Horseman episode "That’s Too Much, Man!" features an extract from Venus near the end of the episode.[75]

- Doctor Who features a brief excerpt from "The Devil’s Triangle" in The Mind of Evil.[74]

- The Man Who Fell to Earth features excerpts of Venus and Mars.[76]

- The Simpsons episode "'Scuse Me While I Miss the Sky" features extracts of the beginning of Jupiter due to astronomy being the main subject of the episode.[77]

- The Simpsons episode "The Regina Monologues" features an extract from Mars in a flashback scene to World War II.[77]

- Mr. Robot features Neptune in the pre-credits sequence of season 2 episode 4.[78]

- John Williams used the melodies and instrumentation of Mars as the inspiration for his soundtrack for the Star Wars films (specifically "The Imperial March").[79]

- Hans Zimmer closely used the melodies, instrumentation and orchestration of Mars as the inspiration for his soundtrack for the movie Gladiator to the extent that a lawsuit for copyright infringement was filed by the Holst foundation.[80]

- Bluey – Animated children's series on ABC TV; Australia – used the Jupiter theme in series two in an episode titled "Sleepytime".

Other uses

- The JR East railway company in Japan uses several excerpts from "Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity" as departure melodies for some train stations in the Greater Kantō region.

See also

Notes

- Holst's appointments diary includes a note of the date of the work's second London performance in January 1914.[26]

References

- Lebrecht 2008, p. 240.

- "London Concerts"' The Musical Times, December 1920, p. 821 (subscription required)

- "HOLST Suite: The Planets" (compares compositions & history), Len Mullenger, Olton Recorded Music Society, January 2000, webpage: MusicWebUK-Holst: in 1913 Holst went on holiday to Majorca with Balfour Gardiner, Arnold Bax, and his brother Clifford Bax, and who spent the entire holiday discussing astrology.

- "The Great Composers and Their Music", Vol. 50, Marshall Cavendish Ltd., London, 1985. I.H. as quoted on p1218

- "1914 • Herr Schönberg in London". www.schoenberg.at.

- Garnham, Alison (23 October 2003). "Hans Keller and the BBC: The Musical Conscience of British Broadcasting, 1959–79". Ashgate – via Google Books.

- Doctor, Jennifer; Doctor, Jennifer Ruth (23 October 1999). "The BBC and Ultra-Modern Music, 1922–1936: Shaping a Nation's Tastes". Cambridge University Press – via Google Books.

- David Lambourn, "Henry Wood and Schoenberg", The Musical Times, Vol. 128, No. 1734 (August 1987), pp. 422–27.

- Short, p. 131

- Boult, Sir Adrian (1967), Liner note to EMI CD 5 66934 2

- Boult p. 35

- "The Definitive CDs" (CD 94), of Holst: The Planets (with Elgar: Enigma Variations), Norman Lebrecht, La Scena Musicale, 1 September 2004, webpage: Scena-Notes-100-CDs Archived 18 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- "'Sir Adrian Boult' on divine-art.com". Archived from the original on 16 May 2008.

- "London Concerts", The Musical Times, April 1919, p. 179 (subscription required).

- Holst, Imogen, A Thematic Catalogue of Gustav Holst's Music. Faber, 1974

- Kennedy, p. 68

- Foreman, Lewis, Music in England 1885–1920, Thames Publishing, 1994

- "London Concerts", The Musical Times, January 1920, p. 32 (subscription required)

- Greene (1995), p. 89

- "Music in the Provinces", The Musical Times, 1 November 1920, p. 769; and "Municipal Music in Birmingham", The Manchester Guardian, 11 October 1920, p. 6

- Holst, Imogen, A Thematic Catalogue of Gustav Holst's Music. Faber, 1974, at page 125

- HOLST: Planets (The) (Holst) / VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: Symphony No. 4 (Vaughan Williams) (1926, 1937) at Naxos.com

- Sanders, Alan, "Gustav Holst Records The Planets", Gramophone, September 1976, p. 34

- "Combined part of 3rd and 4th flute" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- David Lambourn, Henry Wood and Schoenberg from The Musical Times, Vol. 128, No. 1734 (August 1987), pp. 422–427

- Short, p. 103

- Collected Facsimile Edition vol. 3, Faber 1979. Introduction by Imogen Holst

- Full score, Bodleian Library MS. Mus.b.18/1-7

- "The Original Original! "The Planets" rec. 1926, restored, Holst conducting Holst / London SO". YouTube. 12 March 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Head (2014): p. 7

- "Gustav Holst and 'The Planets'". The History Press. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Weir, William (14 September 2014). "A Little Bit Softer Now, a Little Bit Softer Now …". Slate. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- "The Planets" (full orchestral score): Goodwin & Tabb, Ltd., London, 1921

- "Holst: The Planets – Sunday 23 Apr 2017, 3pm – Royal Festival Hall London – Philharmonia Orchestra". Philharmonia Orchestra.

- "Prom 14: Holst – The Planets". BBC Music Events.

- "London Symphony Orchestra – Holst The Planets". lso.co.uk.

- "Find classical music concert listings – Holst – The Planets, Op.32 – by Bachtrack for classical music, opera, ballet and dance event reviews". bachtrack.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kemp, Linsay (1996) Liner notes to Decca CD 452–303–2

- Hambrick, Jennifer. "The Missing Planet: Watch Leonard Bernstein Improvise 'Pluto, the Unpredictable'". WOSU Public Media. WOSU Radio. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Scott Rohan, Michael, Review, Gramophone, August 2001, p. 50

- "Holst: The Planets; Matthews: Pluto". Hyperion Records.

- "Earth, The, from "The Planets" by Trouvère". Wind Repertory Project. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- Notes from Amazon, webpage: amazon.ca/Planets-World-Premiere.

- Notes to The Planets, Arranged for Two Pianos by the Composer, J. Curwen & Sons, London.

- Holst: Music for Two Pianos, Naxos catalogue no. 8.554369, About This Recording

- "History of the Pianola – Pianola Repertoire". Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Peter Sykes. " Holst: The Planets Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine." HB Direct, Released 1996.

- "Peter Sykes". Peter Sykes. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- "Universal Edition". Universal Edition. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "George Morton, arranging". George Morton. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Isao Tomita. " Tomita's Planets." HB Direct, Released 1976

- Grogan, Christopher. Imogen Holst: A Life in Music. Boydell Press (2010), p. 422

- https://sakermusic.eu/product/gustav-holst-mars-the-bringer-of-war-from-the-planets/

- Stephen Roberts at 4barsrest.com

- Archived 15 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 25 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Tapspace :: Solo & Ensemble :: Mercury (from "The Planets")". Archived from the original on 31 July 2013.

- "Song History for The Cavaliers", Retrieved 31 March 2013

- "King Crimson – Mars". Paste Magazine.

- "Aeon "Aeons Black"". Metal Blade Records.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "BBC Two – Classic Albums, Black Sabbath: Paranoid". Bbc.co.uk. 26 October 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- "Black Sabbath Dies Irae [Full Bootleg – Live in Italy – 1990]" – via www.youtube.com.

- "YouTube". www.youtube.com.

- Malfarius (3 March 2015). "Saxon – 10 Years Of Denim And Leather 1989 Full Concert" – via YouTube.

- 平原綾香 (Hirahara Ayaka) at last.fm (in English)

- "O God Beyond All Praising". Oremus. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- "We Praise You and Acknowledge You, O God". Hymnary.org. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- Rayner, Gordon (24 September 2015). "Rugby World Cup: fans petition ITV to replace 'truly awful' Paloma Faith theme music". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Gabler, Jay (8 July 2014). "Holst and hops: Bells Brewery releasing beers inspired by "The Planets"". Classical MPR. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Heinlein, Robert (1961). Stranger in a Strange Land. G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-441-79034-0.

- Lochner, Jim. "CD Review: The Right Stuff". filmscoreclicktrack.com. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Martin, Bill (1 December 1998). Listening to the Future: The Time of Progressive Rock, 1968–1978. Chicago and La Salle, Illinois: Carus Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 9780812693683.

- {{|url= https://www.tunefind.com/show/bojack-horseman/season-3/36739

- Gent, James (14 September 2016). "'The Man Who Fell To Earth: Original Soundtrack'". We Are Cult.

- Bennett, James (10 May 2017). "This Flash Mob of Holst's 'Jupiter' Will Bring You Jollity". wqxr.org. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Mr. Robot Soundtrack: S2 · E4 · eps2.2_init1.asec". tunefind.com. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Shobe, Michael. and Kim Nowack. "The Classical Music Influences Inside John Williams' 'Star Wars' Score," WQXR (Dec 17, 2015).

- Carlsson, Mikael. "Zimmer sued over 'Gladiator' music" (Jun 12, 2006).

Sources

- Boult, Adrian (1973). My Own Trumpet. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-02445-5.

- Greene, Richard (1995). Holst: The Planets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45633-9.

- Head, Raymond (2014). Gustav Holst: The Planets Suite - New Light on a Famous Work. Sky Dance Press. ISBN 978-0-9928464-0-4.

- Kennedy, Michael (1987). Adrian Boult. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-333-48752-4.

- Lebrecht, Norman (2008). The Life and Death of Classical Music: Featuring the 100 Best and 20 Worst Recordings Ever Made. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-48746-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Short, Michael (1990). Gustav Holst: The Man and his Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-314154-X.

External links

- Links to public domain scores of The Planets:

- The Planets: Suite for Large Orchestra (Score in the Public Domain)

- The Planets: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Thaxted sheet music (PDF)

- Online recordings:

- Free MIDI recordings of "The Planets" (containing some errors, however)

- IMDB entry for the 1983 Ken Russell documentary The Planets

- Sheet music:

- The Planets Suite (contains rare complete piano arrangement of Jupiter)