The Marais

Le Marais (French pronunciation: [lə maʁɛ] (![]()

History

Paris aristocratic district

In 1240, the Order of the Temple built its fortified church just outside the walls of Paris, in the northern part of the Marais. The Temple turned this district into an attractive area, which became known as the Temple Quarter, and many religious institutions were built nearby: the des Blancs-Manteaux, de Sainte-Croix-de-la-Bretonnerie and des Carmes-Billettes convents, as well as the church of Sainte-Catherine-du-Val-des-Écoliers.

During the mid-13th century, Charles I of Anjou, King of Naples and Sicily, and brother of King Louis IX of France built his residence near the current n°7 rue de Sévigné.[2] In 1361 the King Charles V built a mansion known as the Hôtel Saint-Pol in which the Royal Court settled during his reign as well as his son's.

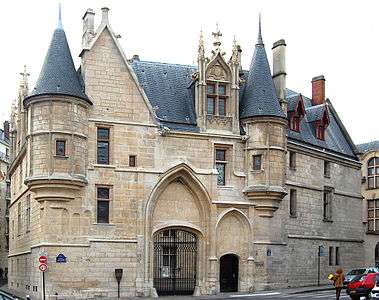

From that time to the 17th century and especially after the Royal Square (Place Royale, current place des Vosges) was designed under King Henri IV of France in 1605, the Marais was the French nobility's favorite place of residence. French nobles built their urban mansions there—hôtels particuliers, in French—such as the Hôtel de Sens, the Hôtel de Sully, the Hôtel de Beauvais, the Hôtel Carnavalet, the Hôtel de Guénégaud and the Hôtel de Soubise, as well as many other hôtels particuliers, found all over the district.

During the late 18th century, the district was no longer the most fashionable district for the nobility, yet it still kept its reputation of being an aristocratic area. By that time, only minor nobles and a few more powerful nobles, such as the Prince de Soubise, lived there. The Place des Vosges remained a place for nobles to meet. The district fell into despair after the French Revolution, and was therefore abandoned by the nobility completely, and would remain so until the present day.

Jewish community

People

After the French Revolution, the district was no longer the aristocratic district it had been during the 17th and 18th centuries. Because of this, the district became a popular and active commercial area, hosting one of Paris' main Jewish communities. At the end of the 19th century and during the first half of the 20th, the district around the rue des Rosiers, referred to as the "Pletzl", welcomed many Eastern European Jews (Ashkenazi) who reinforced the district's clothing specialization. During World War II the Jewish community was targeted by the Nazis who were occupying France. As of today the rue des Rosiers remains a major centre of the Paris Jewish community, which has made a comeback since the 1990s. Public notices announce Jewish events, bookshops specialize in Jewish books, and numerous restaurants and other outlets sell kosher food.

Institutions

The synagogue on 10 rue Pavée is adjacent to the rue des Rosiers.[3] It was designed in 1913 by Art Nouveau architect Hector Guimard, who designed several Paris Metro stations. Le Marais houses the Museum of Jewish Art and History, the largest French museum of Jewish art and history. The museum conveys the rich history and culture of Jews in Europe and North Africa from the Middle Ages to the 20th century.[4][5]

Historic events

In 1982, Palestinian terrorists murdered 6 people and injured 22 at a Jewish restaurant in Le Marais, Chez Jo Goldenberg, an attack which evidence ties to the Abu Nidal Organization.[6][7][8]

Post-war rehabilitation

By the 1950s, the district had become a working-class area and most of its architectural masterpieces were in a bad state of repair. In 1964, General de Gaulle's Culture Minister Andre Malraux made the Marais the first secteur sauvegardé (literally safeguarded sector). These were meant to protect and conserve places of special cultural significance. In the following decades the government and the Parisian municipality led an active restoration and Rehabilitation Policy.

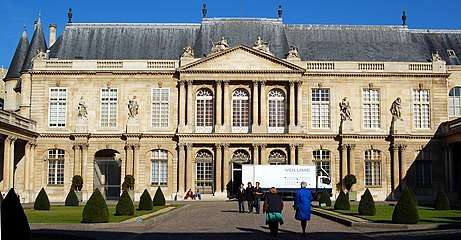

The main Hôtels particuliers have been restored and turned into museums: the Hôtel Salé hosts the Picasso Museum, the Hôtel Carnavalet hosts the Paris Historical Museum, the Hôtel Donon hosts the Cognacq-Jay Museum, the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan hosts the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme. The site of Beaubourg, the western part of Marais, was chosen for the Centre Georges Pompidou, France's national Museum of Modern Art and one of the world's most important cultural institutions. The building was completed in 1977 with revolutionary architecture by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers.

Today's Marais

The Marais is now one of Paris' main localities for art galleries. Following its rehabilitation, the Marais has become a fashionable district, home to many trendy restaurants, fashion houses, and hip galleries.

The Marais is also known for the Chinese community it hosts. The community began to appear during World War I. At that time, France needed workers to replace its at-war soldiers and China decided to send a few thousand of its citizens on the condition that they would not take part in the war. After the 1918 victory, some of them decided to stay in Paris, specifically living around the current rue au Maire. Today, most work in jewellery and leather-related products. The Marais' Chinese community has settled in the north of the district, particularly in the surrounding of Place de la République. Next to it, on the Rue du Temple, is the Chinese Church of Paris.

Other features of the neighbourhood include the Musée Picasso, the house of Nicolas Flamel, the Musée Cognacq-Jay, and the Musée Carnavalet.

LGBT culture

Le Marais became a centre of LGBT culture, beginning in the 1980s. As of today, 40% of the LGBT businesses in Paris are in Le Marais. Florence Tamagne, author of Paris: 'Resting on its Laurels'?, wrote that Le Marais "is less a 'village' where one lives and works than an entrance to a pleasure area" and that this differentiates it from Anglo-American gay villages.[9] Tamagne added that like U.S. gay villages, Le Marais has "an emphasis on 'commercialism, gay pride and coming-out of the closet'".[9]Le Dépôt, one of the largest cruising bars in Europe as of 2014 (per Tamagne), is in the Le Marais area.[9]

- Gay village in Le Marais

Notable residents

According to sources, the following are people of note:

- Maximilien de Béthune, duc de Sully†

- Urbain de Maillé-Brézé†

- Armand de Vignerot du Plessis†

- Princes of Rohan Soubise

- Catherine de Vivonne, marquise de Rambouillet†

- Marie de Rabutin-Chantal, marquise de Sévigné†

- Maximilien Robespierre†

- Victor Hugo†

- John Galliano

- Jacques Frémontier (born surname Friedman; 1930–2020)

- Jack Lang

- Dominique Strauss-Kahn and Anne Sinclair

- Jim Morrison†[10][11]

Places and monuments of note

According to sources, the following are places and monuments of note:

- National Archives, including the Hôtel de Soubise and Hôtel de Rohan

- Carnavalet Museum

- Church Notre-Dame-des-Blancs-Manteaux

- Church of St-Gervais-et-St-Protais

- Church Saint-Merri

- Church of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs

- Church of Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis

- Hôtel d'Angoulême Lamoignon (housing the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris and the Hôtel-Lamoignon - Mark Ashton Garden.

- Hôtel d'Aumont

- Hôtel de Beauvais

- Hôtel de Sens

- Hôtel de Sully

- Place des Vosges, including the home of Victor Hugo and Café Ma Bourgogne

- Maison européenne de la photographie in the Hôtel de Camtobre (1706)

- Mémorial de la Shoah, including the Memorial of the Unknown Jewish Martyr and the CDJC

- Musée Cognacq-Jay

- Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme (housed in the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan)

- Musée des Arts et Métiers

- Musée Picasso

- Place des Émeutes-de-Stonewall (Stonewall riots square)

- Place Harvey Milk

- Pletzl, the historic Jewish quarter

- Rosiers – Joseph Migneret Garden

- Temple du Marais

Gallery

Jo Goldenberg's Jewish delicatessen (now defunct) on the rue des Rosiers; site of the Goldenberg restaurant attack

Jo Goldenberg's Jewish delicatessen (now defunct) on the rue des Rosiers; site of the Goldenberg restaurant attack_01.jpg) Chez Marianne, a Jewish restaurant in Le Marais

Chez Marianne, a Jewish restaurant in Le Marais Restaurant Pitchi Poï in the predominantly Jewish Pletzl quarter

Restaurant Pitchi Poï in the predominantly Jewish Pletzl quarter Murciano Jewish bakery in the rue des Rosiers

Murciano Jewish bakery in the rue des Rosiers Hôtel de Sens

Hôtel de Sens Hôtel Soubise

Hôtel Soubise Maison de Jean Herouet

Maison de Jean Herouet Entrance of l'Hôtel d'Almeras

Entrance of l'Hôtel d'Almeras- Interior of Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais Church

- Saint-Paul Saint-Louis Church

Hôtel Salé (Picasso Museum)

Hôtel Salé (Picasso Museum) Place des Vosges

Place des Vosges Medieval cellar of the Hôtel de Beauvais

Medieval cellar of the Hôtel de Beauvais- Medieval houses in rue Miron

Reading room in the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris (City of Paris History Library)

Reading room in the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris (City of Paris History Library) View of rue Aubriot

View of rue Aubriot Temple du Marais, a Protestant church

Temple du Marais, a Protestant church- Courtyard of the Hotel de Saint-Aignan, which houses the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme

See also

- LGBT culture in Paris

- Musée Picasso

- Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme

- History of the Jews in France

- Musée Carnavalet

- Rue des Rosiers

- Goldenberg restaurant attack

References

- "Le Marais in Paris". Paris Digest. 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- This hôtel remained until 1868, and the rue du Roi-de-Sicile is named after it.

- JARRASSE Dominique, Guide du patrimoine juif parisien, éditions Parigramme, 2003, p. 121-125.

- Godet, Jean-Christophe (2011). "Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme," TimeOut Paris (online, September 13), see , accessed 15 November 2015.

- "Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme".

- Samuel, Henry (June 17, 2005). "Suspected mastermind of 1982 Paris Jewish restaurant attack 'bailed in Jordan'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Massoulié, François (1999). Middle East Conflicts. Interlink Illustrated Histories. Northampton, MA, USA: Interlink Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-1566562379. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Harrison, Michael M. (1994). "France and International Terrorism: Problem and Response". In Charters, David (ed.). The Deadly Sin of Terrorism: Its Effect on Democracy and Civil Liberty in Six Countries. Contributions in Political Science, No. 340 (Johnpoll, B.K., ser. ed.). Westport, CT, USA: ABC-CLIO/Greenwood. p. 108. ISBN 978-0313289644. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Tamagne, Florence (2014). "Paris: 'Resting on its Laurels'?" (Chapter 12). In: Evans, Jennifer V. and Matt Cook. Queer Cities, Queer Cultures: Europe since 1945, pp. 240, 250, London, ENG: Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 144114840X, 9781441148407, see 240 and , accessed 15 November 2015.

- Anon. (July 9, 1971). "Jim Morrison: Lead rock singer dies in Paris". The Toronto Star. United Press International. p. 26.

- Young, Michelle (July 1, 2014). "The Apartment in Paris Where Jim Morrison Died at 17 Rue Beautreillis". Untapped Cities. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

Further reading

- Caron, David (2009). My Father and I : The Marais and the Queerness of Community. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801447730. OCLC 263065358.

- Sibalis, Michael. "Urban Space and Homosexuality: The Example of the Marais, Paris' 'Gay Ghetto'" (Wilfrid Laurier University). Urban Studies. August 2004 vol. 41 no. 9 p. 1739-1758. DOI 10.1080/0042098042000243138.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Le Marais. |

- Le Marais

- Le Marais: The Indifferent Ghetto Article about Le Marais as the gay neighbourhood of Paris

- Gay Paris: English speaking gay walks in Paris

- ParisMarais.com: the official guide, partner of the Paris Tourist Office

- Le Marais photos

- Marais district Photographs

- My Gay Paris The latest news on Paris and Le Marais with a gay perspective