Student strike of 1970

The student strike of 1970 was a massive protest across the United States, that included walk-outs from college and high school classrooms initially in response to the United States expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. The strike began May 1, but increased significantly after the shooting of students at Kent State University by National Guardsmen on May 4. While many violent incidents occurred during the protests, they were, for the most part, peaceful.

| Student strike of 1970 | |

|---|---|

| Part of Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War | |

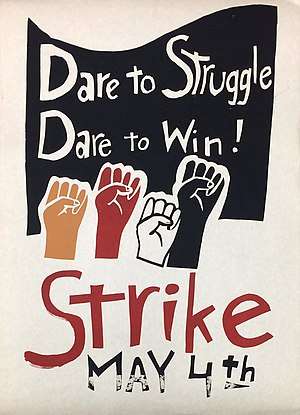

Poster advertising the student strike | |

| Date | May 1 - 8, 1970 |

| Location | |

| Caused by |

|

| Methods | |

| Resulted in | Political backlash |

To some Americans, the protests were seen as chaotic and harmful. Conservative elements in the country began to view the anti-war movement with more distaste.

History

Announcement of Cambodian campaign

On April 30, 1970, President Nixon announced the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia.[1][2] On May 1, protests on college campuses and in cities throughout the U.S. began. In Seattle, over a thousand protestors gathered at the Federal Courthouse and cheered speakers. Significant protests also occurred at the University of Maryland, the University of Cincinnati, and Princeton University.[3]

Kent State shootings and reactions

At Kent State University in Ohio, a demonstration with about 500 students was held on the Commons.[4] On May 2, students burned down the ROTC building at Kent State. On May 4, poorly trained National Guardsmen confronted and killed four students while injuring ten other by bullets during a large protest demonstration at the college. Soon, more than 450 university, college and high school campuses across the country were shut down by student strikes and both violent and non-violent protests that involved more than 4 million students.[5][6][3]

Continued protests

While opposition to the Vietnam War had been simmering on American campuses for several years, and the idea of a strike had been introduced by the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, which advocated a general strike on the 15th of every month until the war ended, the Kent State shootings seemed to provide the spark for students across the US to adopt the strike tactic.

On May 7, violent protests began at the University of Washington with some students smashing windows in their Applied Physics laboratory and throwing rocks at the police while chanting "the pigs are coming!"[3]

On May 8, ten days after Nixon announced the Cambodian invasion (and 4 days after the Kent State shootings), 100,000 protesters gathered in Washington and another 150,000 in San Francisco.[7] Nationwide, students turned their anger on what was often the nearest military facility—college and university Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) offices. All told, 30 ROTC buildings went up in flames or were bombed. There were violent clashes between students and police at 26 schools and National Guard units were mobilized on 21 campuses in 16 states.[8] Walkouts and protests were reported by the National Strike Information Center at over 700 campuses across the country, with heavy concentrations in New England, the Midwest, and California.[9]

For the most part, however, the protests were peaceful — if often tense. Students at New York University, for example, hung a banner out of a window which read "They Can't Kill Us All."[10]

Protests by university

University of North Carolina

UNC had reputation in the state, particularly among conservatives, as a center of liberalism and activism. The campus began building this reputation under Frank Porter Graham, its president from 1930 to 1949, who was a strong advocate of social welfare and improving the work conditions in the state's textile mills.[11] The Cold War, with its rampant anti-communism rhetoric, raged during the fifties and sixties. UNC found itself the focus of verbal attacks by conservative commentators like future senator Jesse Helms, an executive at Raleigh's WRAL-TV who finished each night's local news with virulent editorials and viewed the campus as a den of Marxists. While UNC did have a Marxist presence, such as the Progressive Labor Club, it was far from the bastion of liberalism that Helms portrayed.[12]

University of Virginia

Strike activities at UVA were highly attended, and led to traffic disruptions and arrests. Marching students halted traffic on highways 250 and 29, and during the worst of the strike, Mayflower moving vans were used as temporary holding cells for arrested protesters. On May 6, students, locals, and people who traveled from across Virginia gathered for a day of rallies at UVA, where state protests were now centered.[13] UVA President Edgar Shannon spoke to the crowd, and was pelted with marshmallows.[13] Shannon had been presented with a list of nine demands from the Student Council, led by its first African American president, James Roebuck.[13] That night, Yippie Jerry Rubin and civil-rights lawyer William Kunstler spoke to an audience of 8,000 at University Hall, a large auditorium not far from the university's historic center in Charlottesville, encouraging students to close down universities nationwide.[13]

On May 5, the University received an injunction to prevent students from occupying Maury Hall, the ROTC building; despite this, a small number of protesters remained there until a small fire broke out in the early hours of Thursday, May 7, forcing them to evacuate.[13] By Friday, May 8, the protests led to police action.[14] The strike had lasting consequences in the months that followed. Student reporting at the time argued that a new Alumni Association was being founded directly in response to strike supporters' activities in an effort to ensure that conservative donors continued to give to the university.[15]

Virginia Commonwealth University

On May 6, 500 students boycotted classes after Virginia Commonwealth University president refused their request that he close the university.[13]

Virginia Polytechnic University

On May 13, 1970, 3,000 Virginia Tech students protested and 57 participated in a hunger strike.[16]

University of Richmond

The student-led Richmond College Senate adopted a resolution condemning Nixon's move into Cambodia.[13]

Yale University

Yale's students were divided during the 1970 protests. Kingman Brewster, Jr. was Yale's president at the time; he had recently risen in popularity among the student body for his tacit support of students' activism in support of fair trials of accused Black Panther Party members.[17] In the lead up to protests over involvement in Cambodia, Brewster urged students not to participate in the strikes and protests and continue going to class as usual, as Yale students had been boycotting classes to join the national student strike against the invasion of Cambodia. By May 4, the Yale Daily News announced that it didn't support involvement in the students strikes occurring across the nation.[18] This decision made it the only Ivy League paper to disagree with the protests.[18] Consequently, fifty protestors visited the News offices and called the editors fascist pigs. In its editorial, the Yale Daily News warned that “radical rhetoric and sporadic violence, such as marked the weekend demonstrations at Yale, only added fuel to the ‘demagoguery of Richard Nixon, Spiro Agnew, John Mitchell and the other hyenas of the right.'"[18]

Political reactions

Fears of insurrection

The protests and strikes had a dramatic impact, and convinced many Americans, particularly within the administration of President Richard Nixon, that the nation was on the verge of insurrection. Ray Price, Nixon's chief speechwriter from 1969–74, recalled the Washington demonstrations saying, "The city was an armed camp. The mobs were smashing windows, slashing tires, dragging parked cars into intersections, even throwing bedsprings off overpasses into the traffic down below. This was the quote, 'student protest. That's not student protest, that’s civil war'."[5]

Not only was Nixon taken to Camp David for two days for his own protection, but Charles Colson (Counsel to President Nixon from 1969 to 1973) stated that the military was called up to protect the administration from the angry students, he recalled that "The 82nd Airborne was in the basement of the executive office building, so I went down just to talk to some of the guys and walk among them, and they're lying on the floor leaning on their packs and their helmets and their cartridge belts and their rifles cocked and you’re thinking, 'This can't be the United States of America. This is not the greatest free democracy in the world. This is a nation at war with itself.'"[5]

Attempted dialogue with students

The student protests in Washington also prompted a peculiar and memorable attempt by President Nixon to reach out to the disaffected students. As historian Stanley Karnow reported in his Vietnam: A History, on May 9, 1970 the President appeared at 4:15 a.m. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to discuss the war with 30 student dissidents who were conducting a vigil there. Nixon "treated them to a clumsy and condescending monologue, which he made public in an awkward attempt to display his benevolence." Nixon had been trailed by White House Deputy for Domestic Affairs Egil Krogh, who saw it differently than Karnow, saying, "I thought it was a very significant and major effort to reach out."[5]

In any regard, neither side could convince the other and after meeting with the students Nixon expressed that those in the anti-war movement were the pawns of foreign communists.[5] After the student protests, Nixon asked H. R. Haldeman to consider the Huston Plan, which would have used illegal procedures to gather information on the leaders of the anti-war movement. Only the resistance of FBI head J. Edgar Hoover stopped the plan.[5]

President's Commission on Campus Unrest

As a direct result of the student strike, on June 13, 1970, President Nixon established the President's Commission on Campus Unrest, which became known as the Scranton Commission after its chairman, former Pennsylvania governor William Scranton. Scranton was asked to study the dissent, disorder, and violence breaking out on college and university campuses.[19]

Conservative backlash

The student protests provoked supporters of the Vietnam War and the Nixon Administration to counter-demonstrate. In contrast to the noisy student protests, Administration supporters viewed themselves as "the Silent Majority" (a phrase coined by Nixon speechwriter Patrick Buchanan).

In one instance, in New York City on May 8, construction workers attacked student protesters in what came to be called the Hard Hat Riot.

See also

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Jackson State killings

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- Opposition to the Vietnam War

References

- Military history of Cambodia

- Richard Nixon Foundation. "President Nixon's Cambodia Incursion Address". YouTube.com. YouTube. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Zoe Altaras. "The May 1970 Student Strike at UW". Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- "Chronology of events". May 4 Task Force. May 4 Task Force. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Director: Joe Angio (2007-02-15). Nixon a Presidency Revealed (television). History Channel.

- Roy Reed, Special to The New York Times, "F.B.I. Investigating Killing Of 2 Negroes in Jackson :Two Negro Students Are Killed In Clash With Police in Jackson", New York Times (1857-Current file) [serial online]. May 16, 1970:1. Available from: ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851 - 2006). Accessed July 28, 2012, Document ID: 80023683.

- Todd Gitlin, The Sixties, New York: Bantam Books, 1987, p. 410.

- Gitlin, p. 410.

- "May 1970 Student Antiwar Strikes". Mapping American Social Movements. University of Washington. 2018.

- "1970 Timeline". New York University. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- Pleasants, Julian M.; Burns, Augustus M. (1990). Frank Porter Graham and the 1950 Senate Race in North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Pressv. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-80786-583-5.

- "Off Campus Access". login.mctproxy.mnpals.net. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Richmond Times Dispatch, 7 May 1970, p. 1. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2:135B950C9F3CF0C6@EANX-14182111DF9B2245@2440714-141688078B4F41E7@0. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.

- Richmond Times Dispatch, 21 May 1970, p. 12. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2:135B950C9F3CF0C6@EANX-14182464E261AA78@2440728-1416877720A65F68@11-1416877720A65F68@. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.

- "The Little Railroad That Thought It Could". The Sally Hemings. [Charlottesville, VA]. 1 (16): 1. May 21, 1970.

- "May 1970 Student Antiwar Strikes - Mapping American Social Movements". depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-22.

- Bloom, Joshua,. Black against empire : the history and politics of the Black Panther Party. Martin, Waldo E., 1951-. Berkeley. ISBN 978-0-520-95354-3. OCLC 820846262.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Charlton, Linda (5 May 1970). "Antiwar Strike Plans in the Colleges Pick Up Student and Faculty Support". New York Times. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- The Report of the President's Commission on Campus Unrest. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1970. Retrieved 2007-04-16. This book is also known as The Scranton Commission Report.

External links

- Photos and Documents: May 1970 Student Strike at the University of Washington, Pacific Northwest Antiwar and Radical History Project.

- Photos from May 1970 student protests and peace vigil at the University of Alabama, from The University of Alabama Encyclopedia collection, William Stanley Hoole Special Collection Library

- An archive containing photos of the 1968-1970 San Francisco State College/University student strike