Stereotype (printing)

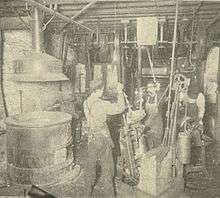

In printing, a stereotype, also known as a cliché, stereoplate or simply a stereo, was a "solid plate of type metal, cast from a papier-mâché or plaster mould (called a flong) taken from the surface of a forme of type"[1] and used for printing instead of the original.

.jpg)

Background

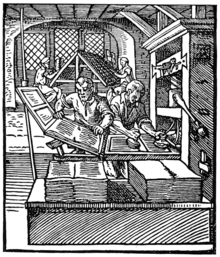

In the days of set movable type, printing involved placing individual letters (called type) plus other elements (including leading and furniture) into a block called a chase. Cumulatively, this full setup for printing a single page was called a forme. Ink was then applied to the forme, pressed against paper and a printed page was made. This process of creating formes was labour-intensive, costly and prevented the printer from using their type, leading, furniture and chases for other work. Furthermore, printers who underestimated demand would be forced to reset the type for subsequent print runs.

… while Nathaniel Hawthorne's publishers assumed that The Scarlet Letter (1850) would do well, printing an uncharacteristically large edition of 2,500 copies, popular demand for Hawthorne's controversial "Custom House" introduction outstripped supply, prompting Ticknor & Fields to reset the type and to reprint another 2,500 copies within two months of the first publication. Still unaware that they had an incipient classic on their hands, Ticknor & Fields neglected at this time to invest in stereotype plates, and thus were forced to pay to reset the type for a third time just four months later when they finally stereotyped the book.[2]

By creating a stereotype, printers could easily reprint documents and free their equipment for other work. The stereotype thus changed the way books, especially novels, magazine articles and other popular forms of literature were reprinted, saving printers the expense of resetting while freeing the type for other jobs.[3] They significantly reduced costs for printers, in that they no longer had to keep expensive type standing for six months, as was a contract requirement with some book printing.[note 1][4]

Even for magazines, stereotype had the advantage that type could be redistributed (broken back out of the form) once the flong was made, and this reduced both wear on the type, and the quantity of type needed. One advantage offered by stereotypes was that the plates could be stored for several decades. A large number of such stored stereotypes were melted down in 1916 in the UK in support of the war effort.[5] Flongs also had a long life is properly stored. In 1941, the United States Government Publishing Office in Washington stored over a quarter of a million flongs, and some of those in use were over thirty years old.[6]

Invention

English sources often describe the process as having been invented in 1725 by William Ged, who apparently stereotyped plates for the Bible at Cambridge University before abandoning the business.[7] However, Count Canstein had been publishing stereotyped Bibles in Germany since 1712 and an earlier form of stereotyping from flong was described in Germany in 1702. It is even possible that the process was used as early as the fifteenth century by Johannes Gutenberg or his heirs for the Mainz Catholicon. Wide application of the technique, with improvements, is attributed to Charles Stanhope in the early 1800s. Printing plates for the Bible were stereotyped in the US in 1814.[8]

Etymologies

Over time, stereotype became a metaphor for any set of ideas repeated identically or with only minor changes. In fact, cliché and stereotype were both originally printers' words, and in their printing senses became synonymous. However, cliché originally had a slightly different meaning, being an onomatopoeic word for the sound that was made during the process of striking a block into molten type metal during another form of stereotyping, later called in English "dabbing".[9][10]

The term stereotype derives from Greek στερεός (stereós) "solid, firm"[11] and τύπος (túpos) "blow, impression, engraved mark"[12] and in its modern sense was coined in 1798.

Newspaper syndication and stereotypes

Initially syndicated news took the form of distributing printed sheets. In December 1841 the owner of the New York Sun had the then US president's address to congress couriered to him. He then printed it on a single sheet, and sold the sheets to newspapers in the surrounding regions, keeping the body, but changing the title head to suit the newspapers. The next effort was to have sheets printed with the president's address on one side and local news on the other.[13][note 2] However, matters improved with improvements in stereotyping and the table summarised Kubel's relation of the growth of stereotyping for syndication.[14]

| Period | Method of distribution of syndicated materials |

|---|---|

| Up to 1850 | Via printed sheets, with either one or both sides printed |

| 1850-1883 | Via printed sheets and stereotype plates |

| Fom 1883 | Largely via stereotype plates |

| From 1895 | Flongs began to replace plates |

| By 1941 | Flongs had almost completely replaced plates |

The flongs distributed were not just syndicated articles or comic strips, but also advertisements. This had a huge advantage in that newspapers avoided the costs of setting these up in type. In some cases flongs were distributed with sections that could be cut out where a local store name could be inserted, so that an illustrated advertisement for a particular product could include the name of the local dealer.[15] Newspapers combined a set of flongs to cast the stereotype plate for a page.

Death of the process

Stereotyping was first challenged by electrotyping, which was originally more expensive and time consuming, but was capable of higher quality printing. It was initially reserved for making copper facsimiles of illustrations. With time, Weedon states that in book publishing, it became more important than stereotyping.[16] However, Kubler stated, in 1941, that in contrast to the United States, which made greater use of electrotyping, European plants used stereotype palates of 75% of all letterpress reproduction work, and that the best stereotype work as equal to the best electrotype work.[17]However, stereotyping retained its primacy in the newspaper trade. Kubler states that alternatives to stereotyping either involved significant additional capital costs or were unsuited for newspapers as they did not allow corrections and the insertion of late news and local materials or were both expensive and unsuitable.[note 3][18][note 4] The first computer-aided typeset book in the UK was Kubler's company was Dylan Thomas' Collected Poems in 1966, but the process really took off in the 1970s, creating enormous disruption in the newspaper industry.[19] Kubler's firm dissolved on 13 August 1979.[20]

Writings on stereotyping

George Adolf Kubler (1876 – 9 January 1944)[21][note 5][22][23][24] was probably the person who wrote most about the process. He was the founder and president of Certified Dry Mat Corporation.[note 6][20] The firm made stereotype matrices or flong mats, which were used to first take a mould from the set-up type, and then to cast the stereotype plates. His writing included:

- A Short History of Stereotyping (1927).[25] Kubler printed 6,000 copies of this short book (93 p., 11 leaves of plates, 24 cm) and distributed it mostly to professional stereotypers, with other copies being sent, only if specially requested, to journalism and trade schools, public libraries and printing craft clubs worldwide.[26] It is available online at the Hathi Trust.

- Historical Treatises, Abstracts, and Papers on Stereotyping (1936).[27] Slightly longer (vii, 169 p., ill., 8º) than his first book, again dealing with the early history of stereotyping.

- Wet Mat Stereotyping in Germany in 1690 (1937).[28] This was a short pamphlet (6 p.) on wet matrix stereotyping, as opposed to the dry matrix approach which Kubler's company promoted.

- The era of Charles Mahon, third Earl of Stanhope, stereotyper, 1750-1825 (1938).[29] This was an illustrated book (viii, 120p., 29 pl., 23cm.) about the British statesman and scientist who invented the first iron printing press and experimented with stereotyping. The book was re-issued by Literary Licencing in 2013 ISBN 9781494034917.

- A New History of Stereotyping (1941).[30] This is a wide ranging book (x, 362 p., ill., 24 cm.) which not only includes a detailed history of the process, but also examines the history of newspaper, alternatives to stereotyping, and even the history of stereotypers' unions. Available on-line at the Internet Archive.

Fleishman provides a thorough and well illustrated explanation of the process in his blog. [15].

Notes

- The specimen agreement between an author and a publisher for publication on a royalty after costs basis included the provision that type, once set up for the book, should be kept standing for six months (to facilitate additional print runs if the book sold well).

- This is the approach seen today with church news sheets, where one side is professionally printed with common material, and the other sides is locally printed with parish specific news.

- Three of the competing processes described by Kubler involved the use of mercury, either as a drip or as admixture with the ink. This would have been a significant hazard for the printers.

- With stereotypes, changes and corrections could be accommodated by cutting out part of the flong and replacing it with a new section.

- Kubler was born in Sharon, Connecticut, United States, and studied at both the University of Munich and the University of Tübingen in Germany. Earning his Doctorate of Jurisprudence in the latter. He was not only interested in printing but was also a passionate collector of prints. When he died in Newark, New Jersey on 9 January 1944, he left a collection of approximately 66,000, high quality engravings clipped from European and American books and periodicals dating almost exclusively from the 19th century. The collection is now part of the archive at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2 East 91st Street, New York, N.Y. 10128.

- The company was finally dissolved on 13 August 1979.

References

- OED, 1ed., vol. 9, part 1, p. 925

- Logan, Peter Melville (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Novel. West Sussex, UK: Blackwell Publishing. p. 677. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- Logan, Peter Melville (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Novel. West Sussex, UK: Blackwell Publishing. p. 676. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- Sprigge, S. Squire (1890). The Methods of Publishing. London: Henry Glaisher. pp. 64–65. Retrieved 2020-07-20 – via The Internet Archive.

- Weedon, Alexis (2016). Victorian Publishing:The Economics of Book Production for a Mass Market, 1836–1916. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-754-63527-7.

- Kubler, Georga Alfred (1941). A New History of Stereotyping. New York: Printed by J. J. Little & Ives Co. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation. p. 331. Retrieved 2020-07-20 – via The Internet Archive.

- "William Ged, (b. 1690, Edinburgh, Scot.—d. Oct. 19, 1749, Leith, Midlothian), Scottish goldsmith who invented (1725) stereotyping". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- Hatch, Harris B.; Stewart, Alexander A. (1918). "History of Stereotyping". Electrotyping and stereotyping. Chicago: United Typothetae of America. pp. 45–49. Primer for apprentices in the printing industry.

- OED, 1st ed., vol. 2, p. 496

- Mosley, James. "Dabbing, abklatschen, clichage..." Type Foundry (blog). Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Stereos, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus

- Tupos, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus

- Kubler, Georga Alfred (1941). A New History of Stereotyping. New York: Printed by J. J. Little & Ives Co. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation. p. 318. Retrieved 2020-07-20 – via The Internet Archive.

- Kubler, Georga Alfred (1941). A New History of Stereotyping. New York: Printed by J. J. Little & Ives Co. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation. p. 324. Retrieved 2020-07-20 – via The Internet Archive.

- Fleischman, Glenn (2019-04-25). "Flong time, no see: How a paper mold transformed the growth of newspapers". Medium. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- Weedon, Alexis (2016). Victorian Publishing:The Economics of Book Production for a Mass Market, 1836–1916. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-754-63527-7.

- Kubler, Georga Alfred (1941). A New History of Stereotyping. New York: Printed by J. J. Little & Ives Co. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation. pp. 325–326. Retrieved 2020-07-20 – via The Internet Archive.

- Kubler, George Adolf (1941). "Inventions for Eliminating Stereotyping". A New History of Stereotyping. New York: Printed by J. J. Little & Ives Co. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation. p. 279-298. Retrieved 2020-07-19 – via Internet Archive.

- Feather, John (2006). "17: The Second Industrial Revolution: The impact of computers". A History of British Publishing (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

- "Certified Dry Mat Corporation". opencorporates: The Open Database Of The Corporate World. 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- "George A. Kubler collection". The Courier-News (Tuesday 11 January 1944): 13. 1944-01-11. Retrieved 2020-07-20 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Secures a Degree: Akron Boy Highly Honored in Germany". The Akron Beacon Journal (Monday 17 November 1902): 8. 1902-11-17. Retrieved 2020-07-20 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bracchi, Jen Cohlman (2011-10-26). "Before Google images: The Kubler Picture Archive at Cooper-Hewitt Library". Unbound: Smithsonian Libraries. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- "George A. Kubler collection". Smithsonian Libraries: Library Catalogue. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- Kubler, George Adolf (1927). A Short History of Stereotyping. New York: Printed by Brooklyn Eagle Commercial Printing Dept. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation. Retrieved 2020-07-19 – via Hathi Trust.

- Kubler, George Adolf (1941). A New History of Stereotyping. New York: Printed by J. J. Little & Ives Co. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation. p. ix. Retrieved 2020-07-19 – via Internet Archive.

- Kubler, George Adolf (1936). Historical Treatises, Abstracts, and Papers on Stereotyping. New York: Printed by J.J. Little and Ives Co. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation.

- George A. Kubler (1937). Wet Mat Stereotyping in Germany in 1690. Certified Dry Mat Corporation.

- Kubler, George Adolf (1938). The Era of Charles Mahon, Third Earl of Stanhope, Stereotyper. New York: Printed by Brooklyn Eagle Press for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation.

- Kubler, George Adolf (1941). A New History of Stereotyping. New York: Printed by J. J. Little & Ives Co. for the Certified Dry Mat Corporation. Retrieved 2020-07-19 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

- Fleishman's blog post is an thorough and well-illustrated introduction to the process.