Statute of Rhuddlan

The Statute of Rhuddlan[n 1] (12 Edw 1 cc.1–12; Welsh: Statud Rhuddlan [ˈr̥ɨðlan]), also known as the Statutes of Wales (Latin: Statuta Valliae) or as the Statute of Wales (Latin: Statutum Valliae), provided the constitutional basis for the government of the Principality of Wales from 1284 until 1536. The Statute introduced English common law to Wales but also permitted the continuance of Welsh legal practices within the Principality. The Statute was superseded by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 when Henry VIII made Wales unequivocally part of the "realm of England".[1]

The statute was not an act of Parliament but rather a royal ordinance made after careful consideration by Edward I on 3 March 1284.[2] It takes its name from Rhuddlan Castle in Denbighshire where it was first promulgated on 19 March 1284.[3] It was formally repealed by the Statute Law Revision Act 1887.[4]

Background

The Prince of Gwynedd had been recognised by the English Crown as Prince of Wales in 1267, holding his lands with the king of England as his feudal overlord. It was thus that the English interpreted the title of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Lord of Aberffraw, which was briefly held after his death by his successor Dafydd ap Gruffudd. This meant that when Llywelyn rebelled, the English interpreted it as an act of treason. Accordingly, his lands escheated to the king of England, and Edward I took possession of the Principality of Wales by military conquest from 1282 to 1283. By this means the principality became "united and annexed" to the Crown of England.[5]

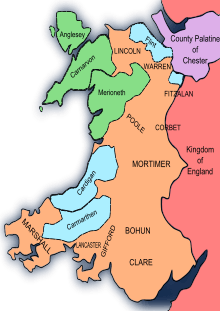

Following his conquest Edward I erected four new marcher lordships in northeast Wales: Chirk (Chirkland), Bromfield and Yale (Powys Fadog), Ruthin (Dyffryn Clwyd) and Denbigh (Lordship of Denbigh); and one in South Wales, Cantref Bychan.[6] He restored the principality of Powys Wenwynwyn to Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn who had suffered at the hands of Llewelyn, and he and his successor Owen de la Pole held it as a marcher lordship. Rhys ap Maredudd of Dryslwyn would have been in a similar position in Cantref Mawr, having adhered to the king during Llewelyn's rebellion, but he forfeited his lands by rebelling in 1287. A few other minor Welsh nobles submitted in time to retain their lands, but became little more than gentry.[7]

The English Crown already had a means of governing South Wales in the honours of Carmarthen and Cardigan, which went back to 1240. These became counties under the government of the Justiciar of South Wales (or of West Wales), who was based in Carmarthen. The changes of the period made little difference in the substantial swathe of land from Pembrokeshire through South Wales to the Welsh Borders which was already in the hands of the marcher lords.[8] Nor did they alter the administration of the royal lordships of Montgomery and Builth, which retained their existing institutions.[9]

New counties

The Statute of Rhuddlan was issued from Rhuddlan Castle in North Wales, one of the "iron ring" of fortresses built by Edward I to control his newly conquered lands.[10] It provided the constitutional basis for the government of what was called "The Land of Wales" or "the king's lands of Snowdon and his other lands in Wales", but subsequently called the "Principality of North Wales".[11] The Statute divided the principality into the counties of Anglesey, Merionethshire, Caernarfonshire, and Flintshire, which were created out of the remnants of the Kingdom of Gwynedd in North Wales.[12] Flintshire was created out of the lordships of Tegeingl, Hopedale, and Maelor Saesneg. It was administered with the Palatinate of Cheshire by the Justiciar of Chester.[13]

The other three counties were overseen by a Justiciar of North Wales and a provincial exchequer at Caernarfon, run by the Chamberlain of North Wales, who accounted to the Exchequer at Westminster for the revenues he collected. Under them were royal officials such as sheriffs, coroners, and bailiffs to collect taxes and administer justice.[14][15] The king had ordered an inquiry into the rents and other dues to which the princes had been entitled, and these were enforced by the new officials. At the local level, commotes became hundreds, but their customs, boundaries and offices remained largely unchanged.

Law in Wales under the Statute

The Statute introduced the English common law system to Wales,[16] but the law administered was not precisely the same as in England. The criminal law was much the same, with felonies such as murder, larceny and robbery prosecuted before the justiciar, as in England. The English writs and forms of action, such as novel disseisin, debt and dower, operated, but with oversight from Caernarfon, rather than the distant Westminster. However, the Welsh practice of settling disputes by arbitration was retained. The procedure for debt was in advance of that in England, in that a default judgment could be obtained. In land law, the Welsh practice of partible inheritance continued, but in accordance with English practice:

- Daughters could inherit their father's lands if there was no son.

- Widows were entitled to dower in a third of their late husband's lands.

- Bastards were excluded from inheriting.[17]

References

Footnote

- The name State of Rutland has been used erroneously by older authors, including Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England; that name properly refer to an unrelated statue made the same year at Rutland in England.

Sources

- Primary

- Bowen, Ivor (1908). The statutes of Wales. London: T. Fisher Unwin. pp. 2–27

- Ruffhead, Owen, ed. (1765). "Statutum Wallie". The Statutes at Large (in Latin). 9. London: Mark Basket; Henry Woodfall & William Stratham. Appendix pp.3–12.

- Secondary

- Bowen 1908, pp. xxviii–xl

- Davies, R. R. (2000). "14: Settlement". The Age of Conquest: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820878-2.

Citations

- The Laws in Wales Act 1535 (A.D. 1535 Anno vicesimo septimo Henrici VIII c. 26)

- Francis Jones (1969). The Princes and Principality of Wales. University of Wales Press.

- G. W. S. Barrow (1956). Feudal Britain: the completion of the medieval kingdoms, 1066-1314. E. Arnold.

- "Statute Law Revision Act 1887, Schedule". electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB).

12 Edw. 1. cc. 1–14 Statuta Wallie (the Statutes of Wales)

- Davies 2000.

- Davies 2000, p. 363.

- Davies 2000, p. 361.

- Davies, R. R. (1987), Conquest, Coexistence and Change: Wales 1063–1415, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ch. 14, ISBN 0-19-821732-3.

- Davies 2000, pp. 357, 364.

- Davies 2000, pp. 357–60.

- Davies 2000, p. 356.

- J. Graham Jones (January 1990). The history of Wales: a pocket guide. University of Wales Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7083-1076-2. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- Davies 2000, p. 364.

- Brian L. Blakeley; Jacquelin Collins (1 January 1993). Documents in British History: Early times to 1714. McGraw-Hill. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-07-005701-2. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- Davies 2000, pp. 364–5.

- Barnett, Hilaire (2004). Constitutional and Administrative Law (5th ed.). Cavendish. p. 59.

- Davies 2000, pp. 367–70.