Sidirokastro

Sidirokastro (Greek: Σιδηρόκαστρο; Bulgarian and Macedonian: Валовища/Валовишта Valovišta; Turkish: Demirhisar) is a town and a former municipality in the Serres regional unit, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Sintiki, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit.[2] It is built near the fertile valley of the river Strymonas, on the bank of the Krousovitis River. Sidirokastro is situated on the European route E79 and the main road from northern Greece (Thessaloniki) to Bulgaria. It has a number of tourist sights, such as the medieval stone castle, Byzantine ruins, and natural spas.

Sidirokastro Σιδηρόκαστρο | |

|---|---|

General view of Sidirokastro | |

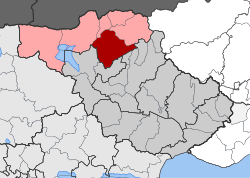

Sidirokastro Location within the regional unit  | |

| Coordinates: 41°14′N 23°23′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Central Macedonia |

| Regional unit | Serres |

| Municipality | Sintiki |

| Municipal unit | Sidirokastro |

| • Municipal unit | 196.6 km2 (75.9 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 9,294 |

| • Municipal unit density | 47/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Community | |

| • Population | 5,693 (2011) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Vehicle registration | ΕΡ |

General information

Sidirokastro is located 25 km to the northwest of the town of Serres, between the Vrontous and Angistro mountains (to the north) and the river Strymonas (to the west). The 2011 census recorded 9,294 residents in the municipal unit of Sidirokastro, while there were 5,693 residents recorded in the community of Sidirokastro and 5,177 in the settlement.[1] The municipal unit has an area of 196.554 km2.[3] The town is crossed by the Krousovitis River, one of the Strymonas' tributaries, which divides the town into two sections. These sections are connected by two bridges: Stavrou and Kalkani. The landscape is made even prettier thanks to the Maimouda rivulet and its miniature bridges. Sidirokastro's population is a blend of indigenous people and descendants of the early 20th century waves of refugees from Asia Minor (people who sought asylum in Greece from the wars and conflicts of that period). Sidirokastro took in refugees from Melnik in 1913; from East Thrace (European Turkey) after the 1922 onslaught that followed the Greco-Turkish Wars in Asia Minor; from Pontus, Vlachs and people from all over Greece. The Kerkini, Angistro and Orvilos mountain ranges form natural boundaries of the greater area and of Greece with neighbouring Balkan countries. The area around Sidirokastro is rich in minerals (marble, lignite, manganese, copper, pyromorphite, iron, chromite, dolomite, uranium) and geothermal springs.

History

Sidirokastro's history reaches a long way back in time. There are Palaeolithic ruins here, and references to the area are found in Homer and Herodotus. Its ancient inhabitants migrated to Sidirokastro from the island of Limnos. The area's first inhabitants were of the Sintian tribe, after which Sintiki Province is named.[4] Sintiki was one of the provinces of the former Serres Prefecture, and Sidirokastro was its capital.

According to the statistics of Geographers Dimitri Mishev and D.M. Brancoff, the town had a total Christian population of 1.535 people in 1905, consisting of 864 Bulgarian Patriarchist Grecomans, 245 Greek Christians, 240 Vlachs, 162 Roma people and 24 Exarchist Bulgarians.[5]

On September 20, 1383, Sidirokastro was overtaken by Ottoman forces and remained under their rule for 529 years. Its name was changed to "Demir Hisar" (Also called "Timurhisar"). Demirhisar was a kaza centre in the Sanjak of Serres before the Balkan Wars.[6] In 1912, Sidirokastro was captured by the Bulgarians under general Georgi Todorov, but some months later it came under Greek control when the Balkan Wars ended. In 1915, during World War I, it came under the control of the Central Powers (Especially Bulgarians), but it remained part of the Greek state when the war ended (1918). In April 1941, after the surrender of the Roupel fortress and the German army's invasion of Greece, the Bulgarian army occupied Sidirokastro, as part of the triple Axis Occupation of Greece. The Bulgarians left in 1944 with the rest of the retreating Axis powers.

Sights

- There are a number of sights to be found in Sidirokastro, such as the ruins of the Byzantine castle, the Agios Dimitrios church that is carved in rock, and the bridges over the Krousovitis River.

- The Issari Fort, built by Emperor Basil II. Standing 155 metres tall, it towers over the town's northwest side. The town owes its name to this fort: "Sidirokastro" means "iron castle" in Greek, as does "Demir Hisar" in Turkish.

- The wetland habitat of the artificial Lake Kerkini, created by a dam on the Strymon River. This singular habitat, protected by the RAMSAR Convention on Wetlands, is Greece's natural frontier with Bulgaria. It is one of the richest fowl habitats in Greece: home to more than 300 species.

- The Sidirokastro Hot Springs have a temperature of 45°. They are just outside the town to the north, near the Strymon River railway-bridge, on a hill that has views of the area. Thousands of people go to these hot springs every year, both for recreation or therapy. There are more hot springs in Thermes and in Angistro.

- Roupel Fort, which was a stronghold against the German-Bulgarian army in World War II.

- The botanic forest-park and the aquarium at Vyronia.

- The ski resort in Lailia is open all year and can accommodate a large number of visitors.

- The town's greatest annual festival is on 27 June, celebrating the area's liberation from Ottoman rule in 1913.

- Mihalis Tsartsidis Folklore and History Museum

Notable natives

- Georgios Sotiriadis, philologist and archaeologist

- Petros Moralis, politician, founding member of PASOK party

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sidirokastro. |

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (in Greek)

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece.

- D. C. Samsaris, Historical Geography of Eastern Macedonia during the Antiquity (in Greek), Thessaloniki 1976 (Society for Macedonian Studies), p. 56-57, 93-94, 120-125. ISBN 960-7265-16-5.

- Dimitri Mishev and D. M. Brancoff, La Macédoine et sa Population Chrétienne, p. 188

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-05-04. Retrieved 2010-04-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)