Scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs and are easily recognized by the pair of grasping pedipalps and the narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back, ending with a venomous stinger. Scorpions range in size from 9 mm / 0.3 in. (Typhlochactas mitchelli) to 23 cm / 9 in. (Heterometrus swammerdami).[1]

| Scorpions | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hottentotta tamulus from Mangaon, Maharashtra, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Scorpiones C. L. Koch, 1837 |

| Families | |

| |

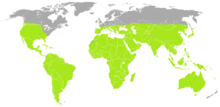

| Native range of Scorpiones | |

The evolutionary history of scorpions goes back to the Silurian period 435 million years ago. They have adapted to a wide range of environmental conditions, and they can now be found on all continents except Antarctica. There are about 1,750 described species,[2] with 13 extant (living) families recognised to date. Their taxonomy is being revised in the light of genomic studies.

All scorpions have a venomous sting, but the vast majority do not represent a serious threat to humans, and in most cases, healthy adults do not need medical treatment after being stung.[3] Only about 25 species have venom capable of killing a human.[4] In some parts of the world with highly venomous species, human fatalities regularly occur, primarily in areas with limited access to medical treatment.[3]

Etymology

The word "scorpion" is thought to have originated in Middle English between 1175 and 1225 AD from Old French scorpion,[5] or from Italian scorpione, both derived from the Latin scorpius,[6] which is the romanization of the Greek word σκορπίος – skorpíos.[7]

Geographical distribution

Scorpions are found on all major land masses except Antarctica. The diversity of scorpions is greatest in subtropical areas; it decreases towards both the poles and the equator.[8] Scorpions did not occur naturally in Great Britain, New Zealand and some of the islands in Oceania, but have now been accidentally introduced into these places by humans. Five colonies of scorpions (Euscorpius flavicaudis) have established themselves in Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey in the United Kingdom.[9] At just over 51°N, this marks the northernmost limit where scorpions live in the wild.[10][11]

Scorpions primarily live in deserts, but can be found in virtually every terrestrial habitat including: high-elevation mountains, caves, and intertidal zones. However, they are largely absent from boreal ecosystems such as: the tundra, high-altitude taiga, and some mountain tops.[12][13] As regards to microhabitats, scorpions may be ground-dwelling, tree-living, rock-loving or sand-loving. Some species, such as Vaejovis janssi, are versatile and are found in every type of habitat in Baja California, while others such as Euscorpius carpathicus, which is endemic to the littoral zone of rivers in Romania, occupy specialized niches.[14]

Evolution

Fossil record

Scorpion fossils have been found in many strata, including marine Silurian and estuarine Devonian deposits, coal deposits from the Carboniferous Period and in amber. Whether the early scorpions were marine or terrestrial has been debated, though they had book lungs like modern terrestrial species.[16][17][18][19] Over 100 fossil species of scorpion have been described.[20] The oldest found to date is Parioscorpio venator, which lived 437 million years ago, during the Silurian. Unlike present day scorpions, but like its marine ancestors, it had compound eyes.[21] Gondwanascorpio from the Devonian is the earliest known terrestrial animal on the Gondwana supercontinent.[22]

Phylogeny

The Scorpiones are a clade of pulmonate Arachnida within the Chelicerata, a subphylum of Arthropoda that contains sea spiders and horseshoe crabs, and terrestrial animals without book-lungs such as ticks and harvestmen. Scorpiones is sister to the Tetrapulmonata, a terrestrial group with book-lungs that contains the spiders and whip scorpions.[16]

| Chelicerata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The internal phylogeny of the scorpions has been debated,[16] but genomic analysis consistently places the Bothriuridae as sister to a clade consisting of Scorpionoidea and "Chactoidea". The scorpions diversified between the Devonian and the early Carboniferous. The main division is into the clades Buthida and Iurida. The Bothriuridae diverged starting before temperate Gondwana broke up into separate land masses. The Iuroidea and Chactoidea are both broken up and are shown as "paraphyletic" (with quotation marks).[23]

| Scorpiones |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taxonomy

Thirteen families and about 1,750 species and subspecies of scorpions have been described. In addition, 111 described taxa of scorpions are extinct.[20] This classification is based on Soleglad and Fet (2003),[24] which replaced Stockwell's older, unpublished classification.[25] Additional taxonomic changes are from papers by Soleglad et al. (2005).[26][27]

The extant taxa to the rank of family (numbers of species in parentheses[28]) are:

- Order Scorpiones

- Parvorder Pseudochactida Soleglad et Fet, 2003

- Superfamily Pseudochactoidea Gromov, 1998

- Family Pseudochactidae Gromov, 1998 (1 sp)

- Superfamily Pseudochactoidea Gromov, 1998

- Parvorder Buthida Soleglad et Fet, 2003

- Superfamily Buthoidea C. L. Koch, 1837

- Family Buthidae C. L. Koch, 1837 (thick-tailed scorpions) (1209 spp)

- Family Microcharmidae Lourenço, 1996, 2019 (17 spp)

- Superfamily Buthoidea C. L. Koch, 1837

- Parvorder Chaerilida Soleglad et Fet, 2003

- Superfamily Chaeriloidea Pocock, 1893

- Family Chaerilidae Pocock, 1893 (51 spp)

- Superfamily Chaeriloidea Pocock, 1893

- Parvorder Iurida Soleglad et Fet, 2003

- Superfamily Chactoidea Pocock, 1893

- Family Chactidae Pocock, 1893 (209 spp)

- Family Euscorpiidae Laurie, 1896 (170 spp)

- Family Superstitioniidae Stahnke, 1940 (1 sp)

- Family Vaejovidae Thorell, 1876 (222 spp)

- Superfamily Iuroidea Thorell, 1876

- Family Caraboctonidae Kraepelin, 1905 (hairy scorpions) (23 spp)

- Family Iuridae Thorell, 1876 (14 spp)

- Superfamily Scorpionoidea Latreille, 1802

- Family Bothriuridae Simon, 1880 (158 spp)

- Family Hemiscorpiidae Pocock, 1893 (=Ischnuridae, =Liochelidae) (rock, creeping, or tree scorpions) (16 spp)

- Family Scorpionidae Latreille, 1802 (burrowing or pale-legged scorpions) (183 spp)

- Superfamily Chactoidea Pocock, 1893

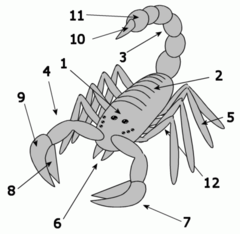

Morphology

1 = Cephalothorax or Prosoma;

2 = Abdomen or Mesosoma;

3 = Tail or Metasoma;

4 = Claws or Pedipalps

5 = Legs;

6 = Mouth parts or Chelicerae;

7 = pincers or Chelae;

8 = Moveable claw or Tarsus;

9 = Fixed claw or Manus;

10 = Stinger or Aculeus;

11 = Telson (anus in previous joint);

12 = Opening of book lungs

The body of a scorpion is divided into two parts (tagmata): the cephalothorax or prosoma, and the abdomen or opisthosoma.[lower-alpha 1] The opisthosoma is subdivided into a broad anterior portion (called the mesosoma or pre-abdomen), and a narrow tail-like posterior (called the metasoma or post-abdomen).[30] The scorpion's exoskeleton is thick and durable, providing good protection from predators.[31]

Cephalothorax

The cephalothorax comprises the carapace, eyes, chelicerae (mouth parts), pedipalps (which have chelae, commonly called claws or pincers) and four pairs of walking legs. Scorpions have two eyes on the top of the cephalothorax, and usually two to five pairs of eyes along the front corners of the cephalothorax. While unable to form sharp images, their central eyes are amongst the most light sensitive in the animal kingdom, especially in dim light, and makes it possible for nocturnal species to use starlight to navigate at night. Some species also have light receptors in their tail.[31] The position of the eyes on the cephalothorax depends in part on the hardness or softness of the soil upon which they spend their lives.[32] The chelicerae are at the front and underneath the carapace. They are pincer-like and have three segments and sharp "teeth".[33][34] The brain of a scorpion is in the back of the cephalothorax, just above the esophagus.[35] Like other arachnids, the scorpion nervous system is highly concentrated in the cephalothorax, but it also has a long ventral nerve cord with segmented ganglia. This may be a "primitive" trait.[36]

The pedipalp is a segmented, chelate (clawed) appendage used for prey immobilization, defense and sensory purposes. The segments of the pedipalp (from closest to the body outwards) are coxa, trochanter, femur (humerus), patella, tibia (including the fixed claw and the manus) and tarsus (moveable claw). A scorpion has darkened or granular raised linear ridges, called "keels" or carinae on the pedipalp segments and on other parts of the body; these are useful taxonomically.[37] Unlike those of some other arachnids, the legs have not been modified for other purposes, though they may occasionally be used for digging, and females may use them to catch emerging young. The legs are covered in proprioceptors, bristles and sensory setae.[38] Depending on the species, the legs may also have spines and spurs.[39]

Mesosoma

The mesosoma or preabdomen is the broad part of the opisthosoma.[30] It consists of the anterior seven somites (segments) of the opisthosoma, each covered dorsally by a sclerotised plate, its tergite. Ventrally, somites 3 to 7 are armoured with matching plates called sternites.[40] The ventral sides of somites 1 and 2 are more complex: the first abdominal sternite is modified into a pair of genital opercula covering the gonopore. Sternite 2 forms the basal plate bearing the pectines. Morphologically the pectines are a pair of limbs that function as sensory organs.[41]

The next four somites, 3 to 6, all bear pairs of spiracles. They serve as openings for the scorpion's respiratory organs, known as book lungs. The spiracle openings may be slits, circular, elliptical or oval according to the species.[42][43] There are thus four pairs of book lungs; each consists of some 140 to 150 thin lamellae filled with air inside a pulmonary chamber, connected on the ventral side to an atrial chamber which opens into a spiracle. Bristles hold the lamellae apart. A muscle opens the spiracle and widens the atrial chamber; dorsoventral muscles contract to compress the pulmonary chamber, forcing air out, and relax to allow the chamber to refill.[44] The 7th and last somite do not bear appendages or any other significant external structures.[42]

The mesosama contains the heart or "dorsal vessel" which is the center of the scorpion's open circulatory system. The heart is continuous with a deep arterial system which spreads throughout the body. Sinuses return deoxygenated blood back to the heart which is re-oxygenated by cardiac pores. The mesosama also contain the reproductive system. The female gonads are made of three or four tubes that run parallel to each other and connected by two to four transverse anastomoses. These tubes are the sites for both oocyte formation and embryonic development. They connect to two oviducts which connect to a single atrium leading to the genital orifice.[34] Males have two gonads made of two cylindrical tubes with a ladder-like configuration, and contain cysts which produce spermatozoa. Both tubes end in a spermiduct located at each side of the mesosama, They connect to glandular symmetrical structures called paraxial organs, which end at the genital orifice. The paraxial organs secrete chitin-based structures which come together to form the spermatophore.[34][45]

Metasoma

The "tail" or metasoma consists of five segments and the telson, which is not strictly a segment. The five segments are merely body rings; they lack apparent sterna or terga, and become larger distally. These segments have keels, setae and bristles which may be used for taxonomic classification. The anus is at the distal and ventral end of the last segment, and is encircled by four anal papillae and the anal arch.[42]

The telson includes the vesicle, which contains a symmetrical pair of venom glands. Externally it bears the curved sting, the hypodermic aculeus or venom-injecting barb. It is equipped with sensory hairs, as the sting cannot be guided visually. Each of the venom glands has its own duct to convey its secretion along the aculeus from the bulb of the gland to immediately subterminal of the point of the aculeus, where each of the paired ducts has its own venom pore.[46]

Biology

Scorpions prefer areas where the temperatures remain between 20 to 37 °C (68 to 99 °F), but may survive temperatures ranging from well below freezing to desert heat.[47][48] Scorpions of the genus Scorpiops living in high Asian mountains, bothriurid scorpions from Patagonia and small Euscorpius scorpions from Central Europe can all survive winter temperatures of about −25 °C (−13 °F). In Repetek (Turkmenistan), seven species of scorpion (of which Pectinibuthus birulai is endemic) live in temperatures varying from −31 to 50 °C (−24 to 122 °F).[49] Most scorpions species are nocturnal or crepuscular, finding shelter during the day in burrows and other shelters such as cracks in rocks and tree bark.[34]

Scorpions make be attacked by other arthropods like ants, spiders, solifugids and centipedes. Major predators include frogs, lizards, snakes, birds and mammals. When threatened, a scorpion raises its claws and tail in a defensive posture. Some species stridulate by rubbing certain hairs, the stinger or the claws. Scorpions host parasites including mites, scuttle flies, nematodes and bacteria.[34]

Diet and feeding

.jpg)

Scorpions generally prey on insects, particularly grasshoppers, crickets, termites, beetles and wasps. They also take spiders. sun spiders, woodlice and even small vertebrates including lizards, snakes and mammals. Species with large claws may prey on earthworms and mollusks. The majority of species are opportunistic and consume a variety of prey though some may be highly specialized. Prey size depends on the size of the size of the species. Several scorpion species are sit-and-wait predators, which involves them waiting for prey at or near the entrance to their burrow. Others will actively seek out them out. Scorpions detect their prey with mechanoreceptive and chemoreceptive hairs on their bodies. Scorpions capture prey with their claws. Small animals are merely killed with the claws, particularly by large-clawed species. Larger and more aggressive prey is given a sting, which can happen very quickly at 0.75 seconds.[34]

Scorpions, like other arachnids, digest their food externally. The chelicerae, which are very sharp, are used to pull small amounts of food off the prey item into a pre-oral cavity below the chelicerae and carapace. The digestive juices from the gut are egested onto the food, and the digested food is then sucked into the gut in liquid form. Any solid indigestible matter (such as exoskeleton fragments) is trapped by setae in the pre-oral cavity and ejected. The sucked-in food is pumped into the midgut by the pharynx, where it is further digested. The waste passes through the hindgut and out of the anus. Scorpions can consume large amounts of food at one sitting. They have an efficient food storage organ and a very low metabolic rate, and a relatively inactive lifestyle. This enables them to survive long periods without food. Some are able to survive 6 to 12 months of starvation.[50] Scorpions excrete very little; their nitrogenous waste consists mostly of insoluble compounds such as xanthine, guanine, and uric acid.[14]

Mating

Most scorpions reproduce sexually, with male and female individuals; however, species in some genera, such as Hottentotta and Tityus, and the species Centruriodes gracilis, Liocheles australasiae, and Ananteris coineaui have been reported, not necessarily reliably, to reproduce through parthenogenesis, in which unfertilized eggs develop into living embryos.[51] Receptive females produce pheromones which are picked up by wandering males using their pectines to comb the substrate. Males begin courtship by moving their bodies back and forth, without moving the legs, a behavior known as juddering. This appears to produce ground vibrations that are picked up by the female.[34]

The pair then make contact using their pedipalps, and perform a "dance" called the promenade à deux ("walk for two"). In this dance, the male and female move backwards and forwards while facing each other, searching for a suitable place for the male to deposit his spermatophore. The courtship ritual can involve several other behaviors such as a cheliceral kiss, in which the male and female grasp each other's chelicerae, and sexual stinging, in which the male stings the female in the chelae or mesosoma to subdue her. When the male has located a suitably stable substrate, such as hard ground, agglomerated sand, rock, or tree bark, he deposits the spermatophore and guides the female over it. This allows the spermatophore to enter her genital opercula, which triggers release of the sperm, thus fertilizing the female. A mating plug then forms in the female to prevent her from mating again before the young are born. The male and female then abruptly separate.[34] Sexual cannibalism after mating has only been reported anecdotally in scorpions.[52]

Birth and development

Unlike the majority of arachnids, which are oviparous, scorpions seem to be universally viviparous.[53] They are also unusual among terrestrial arthropods in the amount of care a female gives to her offspring.[54] Gestation can last for over a year in some species.[55] The size of a brood varies by species, from three to over 100. Before giving birth, the female elevates the front of her body and positions her pedipalps and front legs under her to catch the young. The young emerge one by one from the genital opercula, expel the embryonic membrane, if any, and are placed on the mother's back where they remain until they have gone though at least one molt.[56]

The period before the first molt is called the pro-juvenile stage; the young are unable to feed or sting, but have suckers on their tarsi, used to hold on to their mother. This period lasts 5 to 25 days, depending on the species. The brood molt for the first time simultaneously and last 6 to 8 hours, which signals the beginning of the juvenile stage.[56] Juveniles generally resemble smaller versions of adults, with fully-developed pincers, trichobothria and stingers. They are still soft and lack pigments, and thus continue to ride on their mother's back for protection. They became harder and more pigmented over the next couple of days. They may leave their mother temporarily, returning when they sense potential danger. Once the tegument is fully hardened, the young can hunt prey on their own and may soon leave their mother.[34] A scorpion may molt six times on average before reaching maturity, which may not occur until it is 6 to 83 months old, depending on the species. They may live up to 25 years.[55]

Fluorescence

Scorpions glow a vibrant blue-green when exposed to certain wavelengths of ultraviolet light such as that produced by a black light, due to the presence of fluorescent chemicals in the cuticle. One fluorescent component is beta-carboline. Accordingly, a hand-held ultraviolet lamp has long been a standard tool for nocturnal field surveys of these animals. Fluorescence occurs as a result of sclerotisation and increases in intensity with each successive instar.[57] This fluorescence may have an active role in scorpion light detection.[58]

Relationship with humans

Stings

All known scorpion species possess venom and use it primarily to kill or paralyze their prey so that it can be eaten. The venom consists of a collection of peptides.[59]

In general, the venom is fast-acting, allowing for effective prey capture; however, as a general rule, scorpions kill their prey with brute force if they can, as opposed to using venom, which is also used as a defense against predators. The venom is a mixture of compounds (neurotoxins, enzyme inhibitors, etc.), each not only causing a different effect, but possibly also targeting a specific animal. Each compound is made and stored in a pair of glandular sacs and is released in a quantity regulated by the scorpion itself. Of the more than one thousand known species of scorpions, only 25 have venom that is deadly to humans; most of those belong to the family Buthidae (including Leiurus quinquestriatus, Hottentotta spp., Centruroides spp., and Androctonus spp.).[14][60]

According to the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, scorpion stings can largely be prevented by wearing long sleeves, long trousers, and leather gloves, and by shaking out clothing, bedding, bathroom towels, or shoes before using them. It recommends workers with a history of severe allergic reactions to insect bites or stings to consider carrying an epinephrine autoinjector (EpiPen), and states that they should wear a medical identification bracelet or necklace identifying their allergy.[61]

First aid for scorpion stings is generally symptomatic. It includes strong analgesia, either systemic (opioids or paracetamol) or locally applied (such as a cold compress). Cases of very high blood pressure are treated with anxiety-relieving medications and medications which lower the blood pressure by widening the diameter of blood vessels.[62] Scorpion envenomation with high morbidity and mortality is usually due to either excessive autonomic activity and cardiovascular toxic effects or neuromuscular toxic effects. Antivenom is the specific treatment for scorpion envenomation combined with supportive measures including vasodilators in patients with cardiovascular toxic effects and benzodiazepines when neuromuscular involvement occurs. Although rare, severe hypersensitivity reactions including anaphylaxis to scorpion antivenin (SAV) are possible.[63]

Medical use of venom toxins

Short-chain scorpion toxins constitute the largest group of potassium (K+) channel-blocking peptides. An important physiological role of the KCNA3 channel, also known as KV1.3, is to help maintain large electrical gradients for the sustained transport of ions such as Ca2+ that controls T lymphocyte (T cell) proliferation. Thus KV1.3 blockers could be potential immunosuppressants for the treatment of autoimmune disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and multiple sclerosis).[65] The venom of Uroplectes lineatus is clinically important in dermatology.[66]

Several scorpion venom toxins have been investigated for medical use. Chlorotoxin from the deathstalker scorpion (Leiurus quinquestriatus); the toxin blocks small-conductance chloride channels;[64][67] Maurotoxin from the venom of the Tunisian Scorpio maurus blocks potassium channels.[68] Some antimicrobial peptides in the venom of Mesobuthus eupeus; meucin-13 and meucin-18 have extensive cytolytic effects on bacteria, fungi, and yeasts,[69] while meucin-24 and meucin-25 selectively kill Plasmodium falciparum and inhibit the development of Plasmodium berghei, both malaria parasites, but do not harm mammalian cells.[70]

Consumption

Fried scorpion is traditionally eaten in Shandong, China.[71] There, scorpions can be cooked and eaten in a variety of ways, such as roasting, frying, grilling, raw, or alive. The stingers are typically not removed, since direct and sustained heat negates the harmful effects of the venom.[72]

Middle Eastern culture

The scorpion is a significant animal culturally, appearing as a motif in art, especially in Islamic art in the Middle East.[73] A scorpion motif is often woven into Turkish kilim flat-weave carpets, for protection from their sting.[74] The scorpion is perceived both as an embodiment of evil and a protective force such as a dervish's powers to combat evil.[73] In another context, the scorpion portrays human sexuality.[73] Scorpions are used in folk medicine in South Asia, especially in antidotes for scorpion stings.[73]

One of the earliest occurrences of the scorpion in culture is its inclusion, as Scorpio, in the 12 signs of the Zodiac by Babylonian astronomers during the Chaldean period. This was then taken up by western astrology.[75]

In ancient Egypt, the goddess Serket was often depicted as a scorpion, one of several goddesses who protected the Pharaoh.[76]

Alongside serpents, scorpions are used to symbolize evil in the New Testament. In Luke 10:19 it is written, "Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you." Here, scorpions and serpents symbolize evil.[77] Revelation 9:3 speaks of "the power of the scorpions of the earth."[78]

Early Bronze Age Jiroft culture scorpion game board, Iran

Early Bronze Age Jiroft culture scorpion game board, Iran

A scorpion motif (two types shown) was often woven into Turkish kilim flatweave carpets, for protection from their sting.[74]

A scorpion motif (two types shown) was often woven into Turkish kilim flatweave carpets, for protection from their sting.[74]

Western culture

The scorpion with its powerful sting has been used as the name or symbol of various products and brands, including Italy's Abarth racing cars.[79] In the Roman army, the scorpio was a torsion siege engine used to shoot a projectile.[80] The British Army's FV101 Scorpion was an armoured reconnaissance vehicle or light tank in service from 1972 to 1994.[81] It holds the Guinness world record for the fastest production tank.[82] A version of the Matilda II tank, fitted with a flail to clear mines, was named the Matilda Scorpion.[83] Several ships of the Royal Navy have been named HMS Scorpion, including an 18-gun sloop in 1803,[84] a turret ship in 1863,[85] and a destroyer in 1910.[86]

A hand- or forearm-balancing asana in modern yoga as exercise with the back arched and one or both legs pointing forwards over the head is called Scorpion pose.[87] A variety of martial arts films and video games have been entitled Scorpion King.[88][89][90] A Montesa scrambler motorcycle was named Scorpion.[91]

Scorpions have equally appeared in western artforms including film and poetry: the surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel made symbolic use of scorpions in his 1930 classic L'Age d'or (The Golden Age),[92] while Stevie Smith's last collection of poems was entitled Scorpion and other Poems.[93]

"Scorpion and snake fighting", Anglo-Saxon Herbal, c. 1050

"Scorpion and snake fighting", Anglo-Saxon Herbal, c. 1050_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Still life with scorpion and frog by Hermenegildo Bustos, 1874

Still life with scorpion and frog by Hermenegildo Bustos, 1874.jpg)

_(5144349428).jpg)

1975 Montesa King Scorpion motorcycle

1975 Montesa King Scorpion motorcycle

See also

- Wilson R. Lourenço – French-Brazilian arachnologist specializing in scorpions

Notes

- As there is currently neither paleontological nor embryological evidence that arachnids ever had a separate thorax-like division, there exists an argument against the validity of the term cephalothorax, which means fused cephalon (head) and the thorax. Similarly, arguments can be formed against use of the term abdomen, as the opisthosoma of all scorpions contains a heart and book lungs, organs atypical of an abdomen.[29]

References

- Rubio, Manny (2000). "Commonly Available Scorpions". Scorpions: Everything About Purchase, Care, Feeding, and Housing. Barron's. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-7641-1224-9.

The Guinness Book of Records claims [...] Heterometrus swammerdami, to be the largest scorpion in the world [9 inches (23 cm)]

- Kovařík, František (2009). "Illustrated catalog of scorpions, Part I" (PDF). Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- "Diseases and Conditions – Scorpion stings". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- Polis 1990, p. 1.

- "Scorpion". American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.). 2003. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- "Scorpion". Dictionary.com. Random House. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- σκορπιός, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus.

- Polis 1990, p. 249.

- Benton, T. G. (1992). "The ecology of the scorpion Euscorpius flavicaudis in England". Journal of Zoology. 226 (3): 351–368. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb07484.x.

- Benton, T. G. (1991). "The life history of Euscorpius flavicaudis (Scorpiones, Chactidae)" (PDF). Journal of Arachnology. 19: 105–110.

- Rein, Jan Ove (2000). "Euscorpius flavicaudis". The Scorpion Files. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- Polis 1990, pp. 251–253.

- Huber, Bernhard A.; Bradley J. Sinclair; K.-H. Lampe (2005). African biodiversity: molecules, organisms, ecosystems. Springer. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-387-24315-3.

- Ramel, Gordon. "The Earthlife Web: The Scorpions". The Earthlife Web. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

- s:The Scottish Silurian Scorpion. The Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. N. S. 1901. Vol. 44. pl. 19

- Howard, Richard J.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Legg, David A.; Pisani, Davide; Lozano-Fernandez, Jesus (2019). "Exploring the evolution and terrestrialization of scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones) with rocks and clocks". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 19 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1007/s13127-019-00390-7. ISSN 1439-6092.

- Scholtz, Gerhard; Kamenz, Carsten (2006). "The book lungs of Scorpiones and Tetrapulmonata (Chelicerata, Arachnida): evidence for homology and a single terrestrialisation event of a common arachnid ancestor". Zoology. 109 (1): 2–13. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2005.06.003. PMID 16386884.

- Dunlop, Jason A.; Tetlie, O. Erik; Prendini, Lorenzo (2008). "Reinterpretation of the Silurian scorpion Proscorpius osborni (Whitfield): integrating data from Palaeozoic and recent scorpions". Palaeontology. 51 (2): 303–320. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00749.x.

- Kühl, G.; Bergmann, A.; Dunlop, J.; Garwood, R. J.; Rust, =J. (2012). "Redescription and palaeobiology of Palaeoscorpius devonicus Lehmann, 1944 from the Lower Devonian Hunsrück Slate of Germany". Palaeontology. 55 (4): 775–787. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01152.x.

- Dunlop, Jason A.; Penney, David; Tetlie, O. Erik; Anderson, Lyall I. (2008). "How many species of fossil arachnids are there" (PDF). Journal of Arachnology. 36 (2): 262–272. doi:10.1636/CH07-89.1.

- Wendruff, Andrew J.; Babcock, Loren E.; Wirkner, Christian S.; Kluessendorf, Joanne; Mikulic, Donald G. (2020). "A Silurian ancestral scorpion with fossilised internal anatomy illustrating a pathway to arachnid terrestrialisation". Scientific Reports. 10 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-56010-z. ISSN 2045-2322.

- Gess, R. W. (2013). "The earliest record of terrestrial animals in Gondwana: a scorpion from the Famennian (Late Devonian) Witpoort Formation of South Africa". African Invertebrates. 54 (2): 373–379. doi:10.5733/afin.054.0206.

- Sharma, Prashant P.; Baker, Caitlin M.; Cosgrove, Julia G.; Johnson, Joanne E.; Oberski, Jill T.; Raven, Robert J.; Harvey, Mark S.; Boyer, Sarah L.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2018). "A revised dated phylogeny of scorpions: Phylogenomic support for ancient divergence of the temperate Gondwanan family Bothriuridae". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 122: 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.01.003. ISSN 1055-7903.

- Soleglad, Michael E.; Fet, Victor (2003). "High-level systematics and phylogeny of the extant scorpions (Scorpiones: Orthosterni)" (multiple parts). Euscorpius. 11: 1–175. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- Scott A. Stockwell (1989). Revision of the Phylogeny and Higher Classification of Scorpions (Chelicerata). Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley

- Soleglad, Michael E.; Fet, Victor; Kovařík, F. (2005). "The systematic position of the scorpion genera Heteroscorpion Birula, 1903 and Urodacus Peters, 1861 (Scorpiones: Scorpionoidea)" (PDF). Euscorpius. 20: 1–38. Retrieved 2008-06-13.

- Fet, Victor; Soleglad, Michael E. (2005). "Contributions to scorpion systematics. I. On recent changes in high-level taxonomy" (PDF). Euscorpius (31): 1–13. ISSN 1536-9307. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- "The Scorpion Files". Jan Ove Rein. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Shultz, Stanley; Shultz, Marguerite (2009). The Tarantula Keeper's Guide. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7641-3885-0.

- Polis 1990, pp. 10–11.

- Chakravarthy, Akshay Kumar; Sridhara, Shakunthala (2016). Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in the Tropics and Sub-tropics. Springer. p. 60. ISBN 978-981-10-1518-2.

- "Department of Entomology". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on 1999-08-22. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- Polis 1990, pp. 16–17.

- Stockmann, Roland (2015). "Introduction to Scorpion Biology and Ecology". In Gopalakrishnakone, P.; Possani, L.; F. Schwartz, E.; Rodríguez de la Vega, R. (eds.). Scorpion Venoms. p. 25–59. ISBN 978-94-007-6403-3.

- Polis 1990, pp. 38.

- Polis 1990, pp. 342.

- Polis 1990, p. 12.

- Polis 1990, p. 20.

- Polis 1990, p. 74.

- Polis 1990, p. 13.

- Knowlton, Elizabeth D.; Gaffin, Douglas D. (2011). "Functionally redundant peg sensilla on the scorpion pecten". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. Springer. 197 (9): 895–902. doi:10.1007/s00359-011-0650-9. ISSN 0340-7594.

- Polis 1990, p. 15.

- Wanninger, Andreas (2015). Evolutionary Developmental Biology of Invertebrates 3: Ecdysozoa I: Non-Tetraconata. Springer. p. 105. ISBN 978-3-7091-1865-8.

- Polis 1990, p. 42–44.

- Lautié, N.; Soranzo, L.; Lajarille, M.-E.; Stockmann, R. (2007). "Paraxial organ of a scorpion: structural and ultrastructural studies of Euscorpius tergestinus paraxial organ (Scorpiones, Euscorpiidae)". Invertebrate Reproduction & Development. 51 (2): 77–90. doi:10.1080/07924259.2008.9652258.

- Yigit, N.; Benli, M. (2010). "Fine structural analysis of the stinger in venom apparatus of the scorpion Euscorpius mingrelicus (Scorpiones: Euscorpiidae)". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases. FapUNIFESP (SciELO). 16 (1): 76–86. doi:10.1590/s1678-91992010005000003. ISSN 1678-9199.

- Hadley, Neil F. (1970). "Water relations of the desert scorpion, Hadrurus arizonensis" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 53 (3): 547–558. PMID 5487163.

- Hoshino, K.; A. T. V. Moura; H. M. G. De Paula (2006). "Selection of environmental temperature by the yellow scorpion Tityus serrulatus Lutz & Mello, 1922 (Scorpiones, Buthidae)" (PDF). Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases. 12 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1590/S1678-91992006000100005.

- Kovařík, František (1998). Štíři [Scorpions] (in Czech). Jihlava: Madagaskar. p. 19. ISBN 978-80-86068-10-7.

- Polis 1990, pp. 296–298.

- Lourenço, W. R. (2008). "Parthenogenesis in scorpions: some history - new data". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases. 14 (1). doi:10.1590/S1678-91992008000100003. ISSN 1678-9199.

- Peretti, A. (1999). "Sexual cannibalism in scorpions: fact or fiction?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 68 (4): 485–496. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1999.tb01184.x. ISSN 0024-4066.

- Warburg, M. R. (2012). "Pre-and post-parturial aspects of scorpion reproduction: a review". European Journal of Entomology. 109 (2): 139–46. doi:10.14411/eje.2012.018.

- Polis 1990, p. 6.

- Polis 1990, p. 161.

- Lourenco, W. R. (2000). "Reproduction in scorpions, with special reference to parthenogenesis" (PDF). In S. Toft; N. Scharff (eds.). European Arachnology. Aarhus University Press. pp. 71–85. ISBN 978-877934-0015.

- Stachel, Shawn J.; Scott A. Stockwell; David L. Van Vranken (August 1999). "The fluorescence of scorpions and cataractogenesis". Chemistry & Biology. 6 (8): 531–539. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80085-4. PMID 10421760.

- Gaffinr, Douglas D.; Lloyd A. Bumm; Matthew S. Taylor; Nataliya V. Popokina; Shivani Mann (2012). "Scorpion fluorescence and reaction to light" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 83 (2): 429–436. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.11.014.

- Rodríguez de la Vega, Ricardo C.; Nicolas Vidal; Lourival D. Possani (2013). "Scorpion Peptides". In Abba J. Kastin (ed.). Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides (2nd ed.). pp. 423–429. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385095-9.00059-2. ISBN 978-0-12-385095-9.

- "Poisonous Animals: Scorpions". ThinkQuest. 2000. Archived from the original on 2005-04-03. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- "Insects and Scorpions". NIOSH. 1 July 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Buma, Adriaan Hopperus; David G. Burris; Alan Hawley; James M. Ryan; Peter F. Mahoney (2009). "Scorpion sting". Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine: A Practical Guide (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 518. ISBN 978-1-84800-351-4.

- Bhoite, R. R.; Bhoite, G.R.; Bagdure, D. N.; Bawaskar, H. S. (2015). "Anaphylaxis to scorpion antivenin and its management following envenomation by Indian red scorpion, Mesobuthus tamulus". Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 19 (9): 547–549. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.164807. PMC 4578200. PMID 26430342.

- DeBin, J. A.; G. R. Strichartz (1991). "Chloride channel inhibition by the venom of the scorpion Leiurus quinquestriatus". Toxicon. 29 (11): 1403–1408. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(91)90128-E. PMID 1726031.

- Chandy, K. George; Heike Wulff; Christine Beeton; Michael Pennington; George A. Gutman; Michael D. Cahalan (May 2004). "K+ channels as targets for specific immunomodulation". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 25 (5): 280–289. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.010. PMC 2749963. PMID 15120495.

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1315. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- Deshane, Jessy; Craig C. Garner; Harald Sontheimer (2003). "Chlorotoxin inhibits glioma cell invasion via matrix metalloproteinase-2". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (6): 4135–4144. doi:10.1074/jbc.M205662200. PMID 12454020.

- Carlier, E.; S. Geib; M. De Waard; V. Avdonin; T. Hoshi; Z. Fajloun; H. Rochat; J.-M. Sabatier; R. Kharrat (2000). "Effect of maurotoxin, a four disulfide-bridged toxin from the chactoid scorpion Scorpio maurus, on Shaker K+ channels". The Journal of Peptide Research. 55 (6): 419–427. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3011.2000.00715.x. PMID 10888198.

- Gao, Bin; Patrick Sherman; Lan Luo; John Bowie; Shunyi Zhu (2009). "Structural and functional characterization of two genetically related meucin peptides highlights evolutionary divergence and convergence in antimicrobial peptides". FASEB Journal. 23 (4): 1230–1245. doi:10.1096/fj.08-122317. PMID 19088182.

- Gao, Bin; Jia Xu; Maria del Carmen Rodriguez; Humberto Lanz-Mendoza; Rosaura Hernández-Rivas; Weihong Du; Shunyi Zhu (2010). "Characterization of two linear cationic antimalarial peptides in the scorpion Mesobuthus eupeus". Biochimie. 92 (4): 350–359. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2010.01.011. PMID 20097251.

- Forney, Matthew (June 11, 2008). "Scorpions for Breakfast and Snails for Dinner". The New York Times.

- "How to Mindfully Eat a Scorpion". HuffPost. 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim (2004). "The scorpion in Muslim folklore". Asian Folklore Studies. 63 (1): 95–123.

- Erbek, Güran (1998). Kilim Catalogue No. 1 (1st ed.). May Selçuk A. S.

- Polis 1990, p. 462.

- "Pharaonic Gods". Egyptian Museum. 13 May 2008. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008.

- Pulpit Commentary on Luke 10, accessed 29 October 2018

- Revelation 9:3

- "Abarth Logo: Design and History". Famouslogos.net. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- Vitruvius, De Architectura, X:10:1-6.

- "FV101 Scorpion: Keeping the Light Tank Relevant". HistoryNet. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Fastest tank". Guinnessworldrecords.com. 26 March 2002. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- Fletcher, David (2017). British Battle Tanks: British-made Tanks of World War II. Bloomsbury. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4728-2003-7.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. p. 291. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- The Times (London), Wednesday, 31 August 1910, p. 5

- YJ Editors; Budig, Kathryn (1 October 2012). "Kathryn Budig Challenge Pose: Scorpion in Forearm Balance". Yoga Journal.

- Wallis, J. Doyle (2004). "Operation Scorpio". DVD Talk. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- "The Scorpion King". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Provo, Frank (2002). "The Scorpion King: Sword of Osiris Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Salvadori, Clement (17 January 2019). "Retrospective: 1974-1977 Montesa Cota 247-T". Rider Magazine. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

Permanyer persisted, built larger engines, and in 1965 showed the 247cc engine (21 horsepower at 7,000 rpm) in a Scorpion motocrosser.

- Weiss, Allen S. (1996). "Between the sign of the scorpion and the sign of the cross: L'Age d'or". In Rudolf E. Kuenzli (ed.). Dada and Surrealist Film. MIT Press. pp. 159–175. ISBN 978-0-262-61121-3.

- "Stevie Smith: Bibliography". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

Sources

- Polis, Gary (1990). The Biology of scorpions. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1249-1. OCLC 18991506.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Scorpiones |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

_(14206708079).jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)