SAT

The SAT (/ˌɛsˌeɪˈtiː/ ess-ay-TEE) is a standardized test widely used for college admissions in the United States. Since it was debuted by the College Board in 1926, its name and scoring have changed several times; originally called the Scholastic Aptitude Test, it was later called the Scholastic Assessment Test, then the SAT I: Reasoning Test, then the SAT Reasoning Test, then simply the SAT.

| Type | Paper-based standardized test |

|---|---|

| Developer / administrator | College Board, Educational Testing Service |

| Knowledge / skills tested | Writing, critical reading, mathematics |

| Purpose | Admission to undergraduate programs of universities or colleges |

| Year started | 1926 |

| Duration | 3 hours (without the essay) or 3 hours 50 minutes (with the essay) |

| Score / grade range | Test scored on scale of 200–800, (in 10-point increments), on each of two sections (total 400–1600). Essay scored on scale of 2–8, in 1-point increments, on each of three criteria (total 6–24). |

| Offered | 7 times annually |

| Countries / regions | Worldwide |

| Languages | English |

| Annual number of test takers | |

| Prerequisites / eligibility criteria | No official prerequisite. Intended for high school students. Fluency in English assumed. |

| Fee | US$52.50 to US$101.50, depending on country.[2] |

| Scores / grades used by | Most universities and colleges offering undergraduate programs in the U.S. |

| Website | sat |

The SAT is wholly owned, developed, and published by the College Board, a private, not-for-profit organization in the United States. It is administered on behalf of the College Board by the Educational Testing Service,[3] which until recently developed the SAT as well.[4] The test is intended to assess students' readiness for college. The SAT was originally designed not to be aligned with high school curricula,[5] but several adjustments were made for the version of the SAT introduced in 2016, and College Board president, David Coleman, has said that he also wanted to make the test reflect more closely what students learn in high school with the new Common Core standards.[6]

The SAT takes three hours to finish, plus 50 minutes for the SAT with essay, and as of 2019 costs US$49.50 (US$64.50 with the optional essay), excluding late fees, with additional processing fees if the SAT is taken outside the United States.[7] Scores on the SAT range from 400 to 1600, combining test results from two 200-to-800-point sections: Mathematics, and Critical Reading and Writing. Although taking the SAT, or its competitor the ACT, is required for freshman entry to many colleges and universities in the United States,[8] many colleges and universities are experimenting with test-optional admission requirements[9] and alternatives to the SAT and ACT.[10] Starting with the 2015–16 school year, the College Board began working with Khan Academy to provide free SAT preparation.[11]

Function

| Education in the United States |

|---|

|

|

|

The SAT is typically taken by high school juniors and seniors.[12] The College Board states that the SAT is intended to measure literacy, numeracy and writing skills that are needed for academic success in college. They state that the SAT assesses how well the test-takers analyze and solve problems—skills they learned in school that they will need in college. However, the test is administered under a tight time limit (speeded) to help produce a range of scores.[13]

The College Board also states that use of the SAT in combination with high school grade point average (GPA) provides a better indicator of success in college than high school grades alone, as measured by college freshman GPA. Various studies conducted over the lifetime of the SAT show a statistically significant increase in correlation of high school grades and college freshman grades when the SAT is factored in.[14] A large independent validity study on the SAT's ability to predict college freshman GPA was performed by the University of California. The results of this study found how well various predictor variables could explain the variance in college freshman GPA. It found that independently high school GPA could explain 15.4% of the variance in college freshman GPA, SAT I (the SAT Math and Verbal sections) could explain 13.3% of the variance in college freshman GPA, and SAT II (also known as the SAT subject tests—in the UC's case specifically Writing, Mathematics IC or IIC, plus a third subject test of the student's choice) could explain 16% of the variance in college freshman GPA. When high school GPA and the SAT I were combined, they explained 20.8% of the variance in college freshman GPA. When high school GPA and the SAT II were combined, they explained 22.2% of the variance in college freshman GPA. When SAT I was added to the combination of high school GPA and SAT II, it added a .1 percentage point increase in explaining the variance in college freshman GPA for a total of 22.3%.[15]

There are substantial differences in funding, curricula, grading, and difficulty among U.S. secondary schools due to U.S. federalism, local control, and the prevalence of private, distance, and home schooled students. SAT (and ACT) scores are intended to supplement the secondary school record and help admission officers put local data—such as course work, grades, and class rank—in a national perspective.[16] However, independent research has shown that high school GPA is better than the SAT at predicting college grades regardless of high school type or quality.[17]

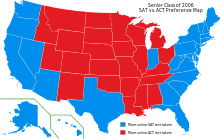

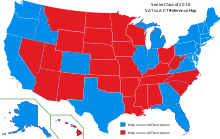

Historically, the SAT was more widely used by students living in coastal states and the ACT was more widely used by students in the Midwest and South; in recent years, however, an increasing number of students on the East and West coasts have been taking the ACT.[18][19] Since 2007, all four-year colleges and universities in the United States that require a test as part of an application for admission will accept either the SAT or ACT, and over 950 four-year colleges and universities do not require any standardized test scores at all for admission.[20][21]

Structure

The SAT has four sections: Reading, Writing and Language, Math (no calculator), and Math (calculator allowed). The test taker may optionally write an essay which, in that case, is the fifth test section. The total time for the scored portion of the SAT is three hours (or three hours and fifty minutes if the optional essay section is taken). Some test takers who are not taking the essay may also have a fifth section, which is used, at least in part, for the pretesting of questions that may appear on future administrations of the SAT. (These questions are not included in the computation of the SAT score.) Two section scores result from taking the SAT: Evidence-Based Reading and Writing, and Math. Section scores are reported on a scale of 200 to 800, and each section score is a multiple of ten. A total score for the SAT is calculated by adding the two section scores, resulting in total scores that range from 400 to 1600. There is no penalty for guessing on the SAT: scores are based on the number of questions answered correctly. In addition to the two section scores, three "test" scores on a scale of 10 to 40 are reported, one for each of Reading, Writing and Language, and Math, with increment of 1 for Reading / Writing and Language, and 0.5 for Math. The essay, if taken, is scored separately from the two section scores.[22]

Reading Test

The Reading Test of the SAT is made up of one section with 52 questions and a time limit of 65 minutes.[22] All questions are multiple-choice and based on reading passages. Tables, graphs, and charts may accompany some passages, but no math is required to correctly answer the corresponding questions. There are five passages (up to two of which may be a pair of smaller passages) on the Reading Test and 10-11 questions per passage or passage pair. SAT Reading passages draw from three main fields: history, social studies, and science. Each SAT Reading Test always includes: one passage from U.S. or world literature; one passage from either a U.S. founding document or a related text; one passage about economics, psychology, sociology, or another social science; and, two science passages. Answers to all of the questions are based only on the content stated in or implied by the passage or passage pair.[23]

Writing and Language Test

The Writing and Language Test of the SAT is made up of one section with 44 multiple-choice questions and a time limit of 35 minutes.[22] As with the Reading Test, all questions are based on reading passages which may be accompanied by tables, graphs, and charts. The test taker will be asked to read the passages, suggest corrections or improvements for the contents underlined. Reading passages on this test range in content from topic arguments to nonfiction narratives in a variety of subjects. The skills being evaluated include: increasing the clarity of argument; improving word choice; improving analysis of topics in social studies and science; changing sentence or word structure to increase organizational quality and impact of writing; and, fixing or improving sentence structure, word usage, and punctuation.[24]

Mathematics

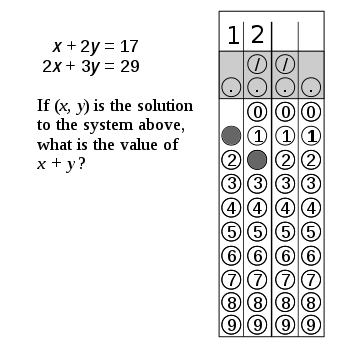

The mathematics portion of the SAT is divided into two sections: Math Test – Calculator and Math Test – No Calculator. In total, the SAT math test is 80 minutes long and includes 58 questions: 45 multiple choice questions and 13 grid-in questions.[25] The multiple choice questions have four possible answers; the grid-in questions are free response and require the test taker to provide an answer.

- The Math Test – No Calculator section has 20 questions (15 multiple choice and 5 grid-in) and lasts 25 minutes.

- The Math Test – Calculator section has 38 questions (30 multiple choice and 8 grid-in) and lasts 55 minutes.

Several scores are provided to the test taker for the math test. A subscore (on a scale of 1 to 15) is reported for each of three categories of math content: "Heart of Algebra" (linear equations, systems of linear equations, and linear functions), "Problem Solving and Data Analysis" (statistics, modeling, and problem-solving skills), and "Passport to Advanced Math" (non-linear expressions, radicals, exponentials and other topics that form the basis of more advanced math). A test score for the math test is reported on a scale of 10 to 40, with an increment of 0.5, and a section score (equal to the test score multiplied by 20) is reported on a scale of 200 to 800. [26][27][28]

Calculator use

All scientific and most graphing calculators, including Computer Algebra System (CAS) calculators, are permitted on the SAT Math – Calculator section only. All four-function calculators are allowed as well; however, these devices are not recommended. All mobile phone and smartphone calculators, calculators with typewriter-like (QWERTY) keyboards, laptops and other portable computers, and calculators capable of accessing the Internet are not permitted.[29]

Research was conducted by the College Board to study the effect of calculator use on SAT I: Reasoning Test math scores. The study found that performance on the math section was associated with the extent of calculator use: those using calculators on about one third to one half of the items averaged higher scores than those using calculators more or less frequently. However, the effect was "more likely to have been the result of able students using calculators differently than less able students rather than calculator use per se."[30] There is some evidence that the frequent use of a calculator in school outside of the testing situation has a positive effect on test performance compared to those who do not use calculators in school.[31]

Style of questions

Most of the questions on the SAT, except for the optional essay and the grid-in math responses, are multiple choice; all multiple-choice questions have four answer choices, one of which is correct. Thirteen of the questions on the math portion of the SAT (about 22% of all the math questions) are not multiple choice.[32] They instead require the test taker to bubble in a number in a four-column grid.

All questions on each section of the SAT are weighted equally. For each correct answer, one raw point is added.[33] No points are deducted for incorrect answers. The final score is derived from the raw score; the precise conversion chart varies between test administrations.

| Section | Average Score 2019 (200 - 800)[1] | Time (Minutes) | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematics | 528 | 25+55=80 | Number and operations; algebra and functions; geometry; statistics, probability, and data analysis |

| Evidence-Based Reading and Writing | 531 | 65+35=100 | Vocabulary, Critical reading, sentence-level reading, Grammar, usage, and diction. |

Logistics

Frequency

The SAT is offered seven times a year in the United States: in August, October, November, December, March, May, and June. For international students SAT is offered four times a year out of USA: in October, December, March and May. The test is typically offered on the first Saturday of the month for the October, November, December, May, and June administrations.[34][35] The test was taken by 2,220,087 high school graduates in the class of 2019.[1]

Candidates wishing to take the test may register online at the College Board's website or by mail at least three weeks before the test date.

Fees

The SAT costs USD $49.50 (GBP £39.50, EUR €43.50) ($64.50 with the optional essay), plus additional fees of over $45 if testing outside the United States) as of 2019.[7] The College Board makes fee waivers available for low income students. Additional fees apply for late registration, standby testing, registration changes, scores by telephone, and extra score reports (beyond the four provided for free).

Accommodation for candidates with disabilities

Students with verifiable disabilities, including physical and learning disabilities, are eligible to take the SAT with accommodations. The standard time increase for students requiring additional time due to learning disabilities or physical handicaps is time + 50%; time + 100% is also offered.

Scaled scores and percentiles

Students receive their online score reports approximately two to three weeks after test administration (longer for mailed, paper scores).[36] Included in the report is the total score (the sum of the two section scores, with each section graded on a scale of 200–800) and three subscores (in reading, writing, and analysis, each on a scale of 2–8) for the optional essay.[37] Students may also receive, for an additional fee, various score verification services, including (for select test administrations) the Question and Answer Service, which provides the test questions, the student's answers, the correct answers, and the type and difficulty of each question.[38]

In addition, students receive two percentile scores, each of which is defined by the College Board as the percentage of students in a comparison group with equal or lower test scores. One of the percentiles, called the "Nationally Representative Sample Percentile", uses as a comparison group all 11th and 12th graders in the United States, regardless of whether or not they took the SAT. This percentile is theoretical and is derived using methods of statistical inference. The second percentile, called the "SAT User Percentile", uses actual scores from a comparison group of recent United States students that took the SAT. For example, for the school year 2019-2020, the SAT User Percentile was based on the test scores of students in the graduating classes of 2018 and 2019 who took the SAT (specifically, the 2016 revision) during high school. Students receive both types of percentiles for their total score as well as their section scores.[37]

Percentiles for Total Scores (2019)

| Score, 400-1600 scale | SAT User | Nationally Representative Sample |

|---|---|---|

| 1600 | 99+ | 99+ |

| 1550 | 99+ | 99+ |

| 1500 | 98 | 99 |

| 1450 | 96 | 99 |

| 1400 | 94 | 97 |

| 1350 | 91 | 94 |

| 1300 | 86 | 91 |

| 1250 | 81 | 86 |

| 1200 | 74 | 81 |

| 1150 | 67 | 74 |

| 1100 | 58 | 67 |

| 1050 | 49 | 58 |

| 1000 | 40 | 48 |

| 950 | 31 | 38 |

| 900 | 23 | 29 |

| 850 | 16 | 21 |

| 800 | 10 | 14 |

| 750 | 5 | 8 |

| 700 | 2 | 4 |

| 650 | 1 | 1 |

| 640–400 | <1 | <1 |

Percentiles for Total Scores (2006)

The following chart summarizes the original percentiles used for the version of the SAT administered in March 2005 through January 2016. These percentiles used students in the graduating class of 2006 as the comparison group.[39][40]

| Percentile | Score 400-1600 scale, (official, 2006) | Score, 600-2400 Scale (official, 2006) |

|---|---|---|

| 99.93/99.98* | 1600 | 2400 |

| 99.5 | ≥1540 | ≥2280 |

| 99 | ≥1480 | ≥2200 |

| 98 | ≥1450 | ≥2140 |

| 97 | ≥1420 | ≥2100 |

| 93 | ≥1340 | ≥1990 |

| 88 | ≥1280 | ≥1900 |

| 81 | ≥1220 | ≥1800 |

| 72 | ≥1150 | ≥1700 |

| 61 | ≥1090 | ≥1600 |

| 48 | ≥1010 | ≥1500 |

| 36 | ≥950 | ≥1400 |

| 24 | ≥870 | ≥1300 |

| 15 | ≥810 | ≥1200 |

| 8 | ≥730 | ≥1090 |

| 4 | ≥650 | ≥990 |

| 2 | ≥590 | ≥890 |

| * The percentile of the perfect score was 99.98 on the 2400 scale and 99.93 on the 1600 scale. | ||

Percentiles for Total Scores (1984)

| Score (1984) | Percentile |

|---|---|

| 1600 | 99.9995 |

| 1550 | 99.983 |

| 1500 | 99.89 |

| 1450 | 99.64 |

| 1400 | 99.10 |

| 1350 | 98.14 |

| 1300 | 96.55 |

| 1250 | 94.28 |

| 1200 | 91.05 |

| 1150 | 86.93 |

| 1100 | 81.62 |

| 1050 | 75.31 |

| 1000 | 67.81 |

| 950 | 59.64 |

| 900 | 50.88 |

| 850 | 41.98 |

| 800 | 33.34 |

| 750 | 25.35 |

| 700 | 18.26 |

| 650 | 12.37 |

| 600 | 7.58 |

| 550 | 3.97 |

| 500 | 1.53 |

| 450 | 0.29 |

| 400 | 0.002 |

The version of the SAT administered before April 1995 had a very high ceiling. In any given year, only seven of the million test-takers scored above 1580. A score above 1580 was equivalent to the 99.9995 percentile.[42]

In 2015 the average score for the Class of 2015 was 1490 out of a maximum 2400. That was down 7 points from the previous class's mark and was the lowest composite score of the past decade.[43]

SAT–ACT score comparisons

The College Board and ACT, Inc., conducted a joint study of students who took both the SAT and the ACT between September 2004 (for the ACT) or March 2005 (for the SAT) and June 2006. Tables were provided to concord scores for students taking the SAT after January 2005 and before March 2016.[44][45] In May 2016, the College Board released concordance tables to concord scores on the SAT used from March 2005 through January 2016 to the SAT used since March 2016, as well as tables to concord scores on the SAT used since March 2016 to the ACT.[46]

In 2018, the College Board, in partnership with the ACT, introduced a new concordance table to better compare how a student would fare one test to another.[47] This is now considered the official concordance to be used by college professionals and is replacing the one from 2016. The new concordance no longer features the old SAT (out of 2,400), just the new SAT (out of 1,600) and the ACT (out of 36).

History

| Year of exam | Reading /Verbal Score | Math Score |

| 1972 | 530 | 509 |

| 1973 | 523 | 506 |

| 1974 | 521 | 505 |

| 1975 | 512 | 498 |

| 1976 | 509 | 497 |

| 1977 | 507 | 496 |

| 1978 | 507 | 494 |

| 1979 | 505 | 493 |

| 1980 | 502 | 492 |

| 1981 | 502 | 492 |

| 1982 | 504 | 493 |

| 1983 | 503 | 494 |

| 1984 | 504 | 497 |

| 1985 | 509 | 500 |

| 1986 | 509 | 500 |

| 1987 | 507 | 501 |

| 1988 | 505 | 501 |

| 1989 | 504 | 502 |

| 1990 | 500 | 501 |

| 1991 | 499 | 500 |

| 1992 | 500 | 501 |

| 1993 | 500 | 503 |

| 1994 | 499 | 504 |

| 1995 | 504 | 506 |

| 1996 | 505 | 508 |

| 1997 | 505 | 511 |

| 1998 | 505 | 512 |

| 1999 | 505 | 511 |

| 2000 | 505 | 514 |

| 2001 | 506 | 514 |

| 2002 | 504 | 516 |

| 2003 | 507 | 519 |

| 2004 | 508 | 518 |

| 2005 | 508 | 520 |

| 2006 | 503 | 518 |

| 2007 | 502 | 515 |

| 2008 | 502 | 515 |

| 2009 | 501 | 515 |

| 2010 | 501 | 516 |

| 2011 | 497 | 514 |

| 2012 | 496 | 514 |

| 2013 | 496 | 514 |

| 2014 | 497 | 513 |

| 2015 | 495 | 511 |

| 2016 | 494 | 508 |

| 2017 | 533 | 527 |

| 2018 | 536 | 531 |

| 2019 | 531 | 528 |

.svg.png)

Many college entrance exams in the early 20th century were specific to each school and required candidates to travel to the school to take the tests. The College Board, a consortium of colleges in the northeastern United States, was formed in 1900 to establish a nationally administered, uniform set of essay tests based on the curricula of the boarding schools that typically provided graduates to the colleges of the Ivy League and Seven Sisters, among others.[49][50]

In the same time period, Lewis Terman and others began to promote the use of tests such as Alfred Binet's in American schools. Terman in particular thought that such tests could identify an innate "intelligence quotient" (IQ) in a person. The results of an IQ test could then be used to find an elite group of students who would be given the chance to finish high school and go on to college.[49] By the mid-1920s, the increasing use of IQ tests, such as the Army Alpha test administered to recruits in World War I, led the College Board to commission the development of the SAT. The commission, headed by eugenicist Carl Brigham, argued that the test predicted success in higher education by identifying candidates primarily on the basis of intellectual promise rather than on specific accomplishment in high school subjects.[50] Brigham "created the test to uphold a racial caste system. He advanced this theory of standardized testing as a means of upholding racial purity in his book A Study of American Intelligence. The tests, he wrote, would prove the racial superiority of white Americans and prevent 'the continued propagation of defective strains in the present population'—chiefly, the 'infiltration of white blood into the Negro.'"[51] In 1934, James Conant and Henry Chauncey used the SAT as a means to identify recipients for scholarships to Harvard University. Specifically, Conant wanted to find students, other than those from the traditional northeastern private schools, that could do well at Harvard. The success of the scholarship program and the advent of World War II led to the end of the College Board essay exams and to the SAT being used as the only admissions test for College Board member colleges.[49]

The SAT rose in prominence after World War II due to several factors. Machine-based scoring of multiple-choice tests taken by pencil had made it possible to rapidly process the exams.[52] The G.I. Bill produced an influx of millions of veterans into higher education.[52][53] The formation of the Educational Testing Service (ETS) also played a significant role in the expansion of the SAT beyond the roughly fifty colleges that made up the College Board at the time.[54] The ETS was formed in 1947 by the College Board, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, and the American Council on Education, to consolidate respectively the operations of the SAT, the GRE, and the achievement tests developed by Ben Wood for use with Conant's scholarship exams.[52] The new organization was to be philosophically grounded in the concepts of open-minded, scientific research in testing with no doctrine to sell and with an eye toward public service.[55] The ETS was chartered after the death of Brigham, who had opposed the creation of such an entity. Brigham felt that the interests of a consolidated testing agency would be more aligned with sales or marketing than with research into the science of testing.[52] It has been argued that the interest of the ETS in expanding the SAT in order to support its operations aligned with the desire of public college and university faculties to have smaller, diversified, and more academic student bodies as a means to increase research activities.[49] In 1951, about 80,000 SATs were taken; in 1961, about 800,000; and by 1971, about 1.5 million SATs were being taken each year.[56]

A timeline of notable events in the history of the SAT follows.

1901 essay exams

On June 17, 1901, the first exams of the College Board were administered to 973 students across 67 locations in the United States, and two in Europe. Although those taking the test came from a variety of backgrounds, approximately one third were from New York, New Jersey, or Pennsylvania. The majority of those taking the test were from private schools, academies, or endowed schools. About 60% of those taking the test applied to Columbia University. The test contained sections on English, French, German, Latin, Greek, history, geography, political science, biology, mathematics, chemistry, and physics. The test was not multiple choice, but instead was evaluated based on essay responses as "excellent", "good", "doubtful", "poor" or "very poor".[57]

1926 test

The first administration of the SAT occurred on June 23, 1926, when it was known as the Scholastic Aptitude Test.[58][59] This test, prepared by a committee headed by Princeton psychologist Carl Campbell Brigham, had sections of definitions, arithmetic, classification, artificial language, antonyms, number series, analogies, logical inference, and paragraph reading. It was administered to over 8,000 students at over 300 test centers. Men composed 60% of the test-takers. Slightly over a quarter of males and females applied to Yale University and Smith College.[59] The test was paced rather quickly, test-takers being given only a little over 90 minutes to answer 315 questions.[58] The raw score of each participating student was converted to a score scale with a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100. This scale was effectively equivalent to a 200 to 800 scale, although students could score more than 800 and less than 200.[52]

1928 and 1929 tests

In 1928, the number of sections on the SAT was reduced to seven, and the time limit was increased to slightly under two hours. In 1929, the number of sections was again reduced, this time to six. These changes were designed in part to give test-takers more time per question. For these two years, all of the sections tested verbal ability: math was eliminated entirely from the SAT.[58]

1930 test and 1936 changes

In 1930 the SAT was first split into the verbal and math sections, a structure that would continue through 2004. The verbal section of the 1930 test covered a more narrow range of content than its predecessors, examining only antonyms, double definitions (somewhat similar to sentence completions), and paragraph reading. In 1936, analogies were re-added. Between 1936 and 1946, students had between 80 and 115 minutes to answer 250 verbal questions (over a third of which were on antonyms). The mathematics test introduced in 1930 contained 100 free response questions to be answered in 80 minutes, and focused primarily on speed. From 1936 to 1941, like the 1928 and 1929 tests, the mathematics section was eliminated entirely. When the mathematics portion of the test was re-added in 1942, it consisted of multiple choice questions.[58]

1941 and 1942 score scales

Until 1941, the scores on all SATs had been scaled to a mean of 500 with a standard deviation of 100. Although one test-taker could be compared to another for a given test date, comparisons from one year to another could not be made. For example, a score of 500 achieved on an SAT taken in one year could reflect a different ability level than a score of 500 achieved in another year. By 1940, it had become clear that setting the mean SAT score to 500 every year was unfair to those students who happened to take the SAT with a group of higher average ability.[60]

In order to make cross-year score comparisons possible, in April 1941 the SAT verbal section was scaled to a mean of 500, and a standard deviation of 100, and the June 1941 SAT verbal section was equated (linked) to the April 1941 test. All SAT verbal sections after 1941 were equated to previous tests so that the same scores on different SATs would be comparable. Similarly, in June 1942 the SAT math section was equated to the April 1942 math section, which itself was linked to the 1942 SAT verbal section, and all SAT math sections after 1942 would be equated to previous tests. From this point forward, SAT mean scores could change over time, depending on the average ability of the group taking the test compared to the roughly 10,600 students taking the SAT in April 1941. The 1941 and 1942 score scales would remain in use until 1995. [60] [61]

1946 test and associated changes

Paragraph reading was eliminated from the verbal portion of the SAT in 1946, and replaced with reading comprehension, and "double definition" questions were replaced with sentence completions. Between 1946 and 1957, students were given 90 to 100 minutes to complete 107 to 170 verbal questions. Starting in 1958, time limits became more stable, and for 17 years, until 1975, students had 75 minutes to answer 90 questions. In 1959, questions on data sufficiency were introduced to the mathematics section, and then replaced with quantitative comparisons in 1974. In 1974, both verbal and math sections were reduced from 75 minutes to 60 minutes each, with changes in test composition compensating for the decreased time.[58]

1960s and 1970s score declines

From 1926 to 1941, scores on the SAT were scaled to make 500 the mean score on each section. In 1941 and 1942, SAT scores were standardized via test equating, and as a consequence, average verbal and math scores could vary from that time forward.[60] In 1952, mean verbal and math scores were 476 and 494, respectively, and scores were generally stable in the 1950s and early 1960s. However, starting in the mid-1960s and continuing until the early 1980s, SAT scores declined: the average verbal score dropped by about 50 points, and the average math score fell by about 30 points. By the late 1970s, only the upper third of test takers were doing as well as the upper half of those taking the SAT in 1963. From 1961 to 1977, the number of SATs taken per year doubled, suggesting that the decline could be explained by demographic changes in the group of students taking the SAT. Commissioned by the College Board, an independent study of the decline found that most (up to about 75%) of the test decline in the 1960s could be explained by compositional changes in the group of students taking the test; however, only about 25 percent of the 1970s decrease in test scores could similarly be explained.[56] Later analyses suggested that up to 40 percent of the 1970s decline in scores could be explained by demographic changes, leaving unknown at least some of the reasons for the decline.[62]

1994 changes

In early 1994, substantial changes were made to the SAT.[63] Antonyms were removed from the verbal section in order to make rote memorization of vocabulary less useful. Also, the fraction of verbal questions devoted to passage-based reading material was increased from about 30% to about 50%, and the passages were chosen to be more like typical college-level reading material, compared to previous SAT reading passages. The changes for increased emphasis on analytical reading were made in response to a 1990 report issued by a commission established by the College Board. The commission recommended that the SAT should, among other things, "approximate more closely the skills used in college and high school work".[58] A mandatory essay had been considered as well for the new version of the SAT; however, criticism from minority groups as well as a concomitant increase in the cost of the test necessary to grade the essay led the College Board to drop it from the planned changes.[64]

Major changes were also made to the SAT mathematics section at this time, due in part to the influence of suggestions made by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Test-takers were now permitted to use calculators on the math sections of the SAT. Also, for the first time since 1935, the SAT would now include some math questions that were not multiple choice, instead requiring students to supply the answers. Additionally, some of these "student-produced response" questions could have more than one correct answer. The tested mathematics content on the SAT was expanded to include concepts of slope of a line, probability, elementary statistics including median and mode, and problems involving counting.[58]

1995 recentering (raising mean score back to 500)

By the early 1990s, average combined SAT scores were around 900 (typically, 425 on the verbal and 475 on the math). The average scores on the 1994 modification of the SAT I were similar: 428 on the verbal and 482 on the math.[65] SAT scores for admitted applicants to highly selective colleges in the United States were typically much higher. For example, the score ranges of the middle 50% of admitted applicants to Princeton University in 1985 were 600 to 720 (verbal) and 660 to 750 (math).[66] Similarly, median scores on the modified 1994 SAT for freshmen entering Yale University in the fall of 1995 were 670 (verbal) and 720 (math).[67] For the majority of SAT takers, however, verbal and math scores were below 500: In 1992, half of the college-bound seniors taking the SAT were scoring between 340 and 500 on the verbal section and between 380 and 560 on the math section, with corresponding median scores of 420 and 470, respectively.[68]

The drop in SAT verbal scores, in particular, meant that the usefulness of the SAT score scale (200 to 800) had become degraded. At the top end of the verbal scale, significant gaps were occurring between raw scores and uncorrected scaled scores: a perfect raw score no longer corresponded to an 800, and a single omission out of 85 questions could lead to a drop of 30 or 40 points in the scaled score. Corrections to scores above 700 had been necessary to reduce the size of the gaps and to make a perfect raw score result in an 800. At the other end of the scale, about 1.5 percent of test takers would have scored below 200 on the verbal section if that had not been the reported minimum score. Although the math score averages were closer to the center of the scale (500) than the verbal scores, the distribution of math scores was no longer well approximated by a normal distribution. These problems, among others, suggested that the original score scale and its reference group of about 10,000 students taking the SAT in 1941 needed to be replaced.[60]

Beginning with the test administered in April 1995, the SAT score scale was recentered to return the average math and verbal scores close to 500. Although only 25 students had received perfect scores of 1600 in all of 1994, 137 students taking the April test scored a 1600.[69] The new scale used a reference group of about one million seniors in the class of 1990: the scale was designed so that the SAT scores of this cohort would have a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 110. Because the new scale would not be directly comparable to the old scale, scores awarded on April 1995 and later were officially reported with an "R" (for example, "560R") to reflect the change in scale, a practice that was continued until 2001.[60] Scores awarded before April 1995 may be compared to those on the recentered scale by using official College Board tables. For example, verbal and math scores of 500 received before 1995 correspond to scores of 580 and 520, respectively, on the 1995 scale.[70]

1995 re-centering controversy

Certain educational organizations viewed the SAT re-centering initiative as an attempt to stave off international embarrassment in regards to continuously declining test scores, even among top students. As evidence, it was presented that the number of pupils who scored above 600 on the verbal portion of the test had fallen from a peak of 112,530 in 1972 to 73,080 in 1993, a 36% backslide, despite the fact that the total number of test-takers had risen by over 500,000.[71] Other authors have argued that the evidence for a decline in student quality is mixed, citing that the reduced use of the SAT by elite colleges has decreased the number of high scorers on that test, that top scorers on the ACT have shown little change in the same period, and that the proportion of 17-year-olds scoring at the highest performance level on the NAEP long-term trend assessment has been roughly stable for decades.[72]

2002 changes – Score Choice

Since 1993, using a policy referred to as "Score Choice", students taking the SAT-II subject exams were able to choose whether or not to report the resulting scores to a college to which the student was applying. In October 2002, the College Board dropped the Score Choice option for SAT-II exams, matching the score policy for the traditional SAT tests that required students to release all scores to colleges.[73] The College Board said that, under the old score policy, many students who waited to release scores would forget to do so and miss admissions deadlines. It was also suggested that the old policy of allowing students the option of which scores to report favored students who could afford to retake the tests.[74]

2005 changes, including a new 2400-point score

In 2005, the test was changed again, largely in response to criticism by the University of California system.[75] In order to have the SAT more closely reflect high school curricula, certain types of questions were eliminated, including analogies from the verbal section and quantitative comparison items from the math section.[58] A new writing section, with an essay, based on the former SAT II Writing Subject Test, was added,[76] in part to increase the chances of closing the opening gap between the highest and midrange scores. Other factors included the desire to test the writing ability of each student; hence the essay. The essay section added an additional maximum 800 points to the score, which increased the new maximum score to 2400.[77] The "New SAT" was first offered on March 12, 2005, after the last administration of the "old" SAT in January 2005. The mathematics section was expanded to cover three years of high school mathematics. To emphasize the importance of reading, the verbal section's name was changed to the Critical Reading section.[58]

Scoring problems of October 2005 tests

In March 2006, it was announced that a small percentage of the SATs taken in October 2005 had been scored incorrectly due to the test papers' being moist and not scanning properly, and that some students had received erroneous scores.[78] The College Board announced they would change the scores for the students who were given a lower score than they earned, but at this point many of those students had already applied to colleges using their original scores. The College Board decided not to change the scores for the students who were given a higher score than they earned. A lawsuit was filed in 2006 on behalf of the 4,411 students who received an incorrect score on the SAT.[79] The class-action suit was settled in August 2007, when the College Board and Pearson Educational Measurement, the company that scored the SATs, announced they would pay $2.85 million into a settlement fund. Under the agreement, each student could either elect to receive $275 or submit a claim for more money if he or she felt the damage was greater.[80] A similar scoring error occurred on a secondary school admission test in 2010–2011, when the ERB (Educational Records Bureau) announced, after the admission process was over, that an error had been made in the scoring of the tests of 2010 students (17%), who had taken the Independent School Entrance Examination for admission to private secondary schools for 2011. Commenting on the effect of the error on students' school applications in The New York Times, David Clune, President of the ERB stated "It is a lesson we all learn at some point—that life isn't fair."[81]

2008 changes

As part of an effort to “reduce student stress and improve the test-day experience", in late 2008 the College Board announced that the Score Choice option, recently dropped for SAT subject exams, would be available for both the SAT subject tests and the SAT starting in March 2009. At the time, some college admissions officials agreed that the new policy would help to alleviate student test anxiety, while others questioned whether the change was primarily an attempt to make the SAT more competitive with the ACT, which had long had a comparable score choice policy.[82] Recognizing that some colleges would want to see the scores from all tests taken by a student, under this new policy, the College Board would encourage but not force students to follow the requirements of each college to which scores would be sent.[83] A number of highly selective colleges and universities, including Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, Cornell, and Stanford, rejected the Score Choice option at the time[84]. Since then, Cornell,[85] University of Pennsylvania,[86] and Stanford[87] have all adopted Score Choice, but Yale[88] continues to require applicants to submit all scores. Others, such as MIT and Harvard, allow students to choose which scores they submit, and use only the highest score from each section when making admission decisions. Still others, such as Oregon State University and University of Iowa, allow students to choose which scores they submit, considering only the test date with the highest combined score when making admission decisions.[89]

2012 changes

Beginning in the fall of 2012, test takers were required to submit a current, recognizable photo during registration. In order to be admitted to their designated test center, students were required to present their photo admission ticket—or another acceptable form of photo ID—for comparison to the one submitted by the student at the time of registration. The changes were made in response to a series of cheating incidents, primarily at high schools in Long Island, New York, in which high-scoring test takers were using fake photo IDs to take the SAT for other students.[90] In addition to the registration photo stipulation, test takers were required to identify their high school, to which their scores as well as the submitted photos would be sent. In the event of an investigation involving the validity of a student's test scores, their photo may be made available to institutions to which they have sent scores. Any college that is granted access to a student's photo is first required to certify that the student has been admitted to the college requesting the photo.[91]

2016 changes, including the return to a 1600-point score

On March 5, 2014, the College Board announced its plan to redesign the SAT in order to link the exam more closely to the work high school students encounter in the classroom.[92] The new exam was administered for the first time in March 2016.[93] Some of the major changes are: an emphasis on the use of evidence to support answers, a shift away from obscure vocabulary to words that students are more likely to encounter in college and career, a math section that is focused on fewer areas, a return to the 1600-point score scale, an optional essay, and the removal of penalty for wrong answers (rights-only scoring).[94] To combat the perceived advantage of costly test preparation courses, the College Board announced a new partnership with Khan Academy to offer free online practice problems and instructional videos.[92]

Name changes

The SAT has been renamed several times since its introduction in 1926. It was originally known as the Scholastic Aptitude Test.[95][58] In 1990, a commission set up by the College Board to review the proposed changes to the SAT program recommended that the meaning of the initialism SAT be changed to "Scholastic Assessment Test" because a "test that integrates measures of achievement as well as developed ability can no longer be accurately described as a test of aptitude".[96][97] In 1993, the College Board changed the name of the test to SAT I: Reasoning Test; at the same time, the name of the Achievement Tests was changed to SAT II: Subject Tests.[95] The Reasoning Test and Subject Tests were to be collectively known as the Scholastic Assessment Tests. According to the president of the College Board at the time, the name change was meant "to correct the impression among some people that the SAT measures something that is innate and impervious to change regardless of effort or instruction."[98] The new SAT debuted in March 1994, and was referred to as the Scholastic Assessment Test by major news organizations.[63][99] However, in 1997, the College Board announced that the SAT could not properly be called the Scholastic Assessment Test, and that the letters SAT did not stand for anything.[100] In 2004, the Roman numeral in SAT I: Reasoning Test was dropped, making SAT Reasoning Test the new name of the SAT.[95]

Math–verbal achievement gap

In 2002, Richard Rothstein (education scholar and columnist) wrote in The New York Times that the U.S. math averages on the SAT and ACT continued their decade-long rise over national verbal averages on the tests.[101]

Reuse of old SAT exams

The College Board has been accused of completely reusing old SAT papers previously given in the United States.[102] The recycling of questions from previous exams has been exploited to allow for cheating on exams and impugned the validity of some students' test scores, according to college officials. Test preparation companies in Asia have been found to provide test questions to students within hours of a new SAT exam's administration.[103][104]

On August 25, 2018, the SAT test given in America was discovered to be a recycled October 2017 international SAT test given in China. The leaked PDF file was on the internet before the August 25, 2018 exam.[105]

Elucidation

Association with culture

For decades many critics have accused designers of the verbal SAT of cultural bias as an explanation for the disparity in scores between poorer and wealthier test-takers.[106] A famous example of this bias in the SAT I was the oarsman–regatta analogy question, which is no longer part of the exam.[107] The object of the question was to find the pair of terms that had the relationship most similar to the relationship between "runner" and "marathon". The correct answer was "oarsman" and "regatta". The choice of the correct answer was thought to have presupposed students' familiarity with rowing, a sport popular with the wealthy. Analogy questions were removed in 2005.

Association with family income

A report from The New York Times stated that family income can explain much of the variance in SAT scores.[108] In response, Lisa Wade, contributor at the website The Society Pages, commented that those with higher family income, “tend to have better teachers, more resource-rich educational environments, more educated parents who can help them with school and, sometimes, expensive SAT tutoring.”[109] However, University of California system research found that after controlling for family income and parental education, the already low ability of the SAT to measure aptitude and college readiness fell sharply while the more substantial aptitude and college readiness measuring abilities of high school GPA and the SAT II each remained undiminished (and even slightly increased). The University of California system required both the SAT and the SAT II from applicants to the UC system during the four years included in the study. They further found that, after controlling for family income and parental education, the tests known as the SAT II measure aptitude and college readiness 10 times higher than the SAT.[15] As with racial bias, correlation with income could also be due to the social class of the makers of the test.

Association with gender

The largest association with gender on the SAT is found in the math section, where male students, on average, score higher than female students by approximately 30 points.[110] In 2013, the American College Testing Board released a report stating that boys outperformed girls on the mathematics section of the test.[111]

Some researchers believe that the difference in scores for both race and gender is closely related to the psychological phenomenon known as stereotype threat. Stereotype threat is thought to occur when an individual who identifies themselves within a subgroup of people encounters a stereotype regarding their subgroup within the content of a test they are taking. Stereotype threat is the conclusion that this, along with additional test anxiety, can cause lower test performance for that individual or group affected. Researchers at Stanford and Waterloo have concluded that stereotype threat may be responsible for the underperformance of about 40 points on the SAT for black and Hispanic students, and about 20 points on the math portion for women.[112][113]Some studies have cautioned that stereotype threat should not be interpreted as a factor in real-world performance gaps.[114][115][116] [117]

Other researchers question these assertions, and point to evidence in support of greater male variability in spatial ability and mathematics. Greater male variability has been found in both body weight, height, and cognitive abilities across cultures, leading to a larger number of males in the lowest and highest distributions of testing[118][119]. This results in a higher number of males scoring in the upper extremes of mathematics tests such as the SAT, resulting in the gender discrepancy.[120]

For the demographics example, students are often asked to identify their race or gender before taking the exam, just this alone is enough to create the threat since this puts the issues regarding their gender or race in front and center of their mind.[121]

For the mathematics example, a question in the May 2016 SAT test involved a chart which identified more boys than girls in mathematics classes overall. Due to this, the girls taking the test might feel that mathematics is not for them and may even feel as if they are not intelligent enough to complete to engage in mathematics and/or the question itself. This is also based on the common stereotype that "men are better at math than women."[113]

For the verbal/reading example, a question in the May 2016 SAT test asked students to analyze and interpret a 19th-century polemic arguing that women's place was at home. The reading passage itself was paired with 1837's “Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism” by Catherine E. Beecher with an 1838 reply from Angelina E Grimké, who was an abolitionist at the time. The Beecher essays argued that women have a lower stature than men and are able to be their best when in domestic situations while Grimké argued that no one's rights should be impinged on the basis of gender. Placement of these passages near the beginning of the test was thought by some critics to sow seeds of self-doubt in female test takers, affecting their performance.[113]

Although aspects of testing such as stereotype are a concern, research on the predictive validity of the SAT has demonstrated that it tends to be a more accurate predictor of female GPA in university as compared to male GPA.[122]

Association with race and ethnicity

African American, Hispanic, and Native American students, on average, perform an order of one standard deviation lower on the SAT than white and Asian students.[123][124][125][126]

Researchers believe that the difference in scores is closely related to the overall achievement gap in American society between students of different racial groups. This gap may be explainable in part by the fact that students of disadvantaged racial groups tend to go to schools that provide lower educational quality. This view is supported by evidence that the black-white gap is higher in cities and neighborhoods that are more racially segregated.[127] It has also been suggested that stereotype threat has a significant effect on lowering achievement of minority students. For example, African Americans perform worse on a test when they are told that the test measures "verbal reasoning ability", than when no mention of the test subject is made.[128] Other research cites poorer minority proficiency in key coursework relevant to the SAT (English and math), as well as peer pressure against students who try to focus on their schoolwork ("acting white").[129] Cultural issues are also evident among black students in wealthier households, with high achieving parents. John Ogbu, a Nigerian-American professor of anthropology, concluded that instead of looking to their parents as role models, black youth chose other models like rappers and did not make an effort to be good students.[130]

One set of studies has reported differential item functioning, namely, that some test questions function differently based on the racial group of the test taker, reflecting differences in ability to understand certain test questions or to acquire the knowledge required to answer them between groups. In 2003, Freedle published data showing that Black students have had a slight advantage on the verbal questions that are labeled as difficult on the SAT, whereas white and Asian students tended to have a slight advantage on questions labeled as easy. Freedle argued that these findings suggest that "easy" test items use vocabulary that is easier to understand for white middle class students than for minorities, who often use a different language in the home environment, whereas the difficult items use complex language learned only through lectures and textbooks, giving both student groups equal opportunities to acquiring it.[131][132] [133] The study was severely criticized by the ETS board, but the findings were replicated in a subsequent study by Santelices and Wilson in 2010.[134][135]

There is no evidence that SAT scores systematically underestimate future performance of minority students. However, the predictive validity of the SAT has been shown to depend on the dominant ethnic and racial composition of the college.[136] Some studies have also shown that African American students under-perform in college relative to their white peers with the same SAT scores; researchers have argued that this is likely because white students tend to benefit from social advantages outside of the educational environment (for example, high parental involvement in their education, inclusion in campus academic activities, positive bias from same-race teachers and peers) which result in better grades.[128]

Christopher Jencks concludes that as a group, African Americans have been harmed by the introduction of standardized entrance exams such as the SAT. This, according to him, is not because the tests themselves are flawed, but because of labeling bias and selection bias; the tests measure the skills that African Americans are less likely to develop in their socialization, rather than the skills they are more likely to develop. Furthermore, standardized entrance exams are often labeled as tests of general ability, rather than of certain aspects of ability. Thus, a situation is produced in which African American ability is consistently underestimated within the education and workplace environments, contributing in turn to selection bias against them which exacerbates underachievement.[128]

Perception

Optional SAT

In the 1960s and 1970s there was a movement to drop achievement scores. After a period of time, the countries, states and provinces that reintroduced them agreed that academic standards had dropped, students had studied less, and had taken their studying less seriously. They reintroduced the tests after studies and research concluded that the high-stakes tests produced benefits that outweighed the costs.[137]

In a 2001 speech to the American Council on Education, Richard C. Atkinson, the president of the University of California, urged dropping the SAT as a college admissions requirement:

Anyone involved in education should be concerned about how overemphasis on the SAT is distorting educational priorities and practices, how the test is perceived by many as unfair, and how it can have a devastating impact on the self-esteem and aspirations of young students. There is widespread agreement that overemphasis on the SAT harms American education.[138]

Even now, no firm conclusions can be reached regarding the SAT's usefulness in the admissions process. It may or may not be biased, and it may or may not serve as a check on grade inflation in secondary schools.[139]

IQ studies

Frey and Detterman (2004) investigated associations of SAT scores with intelligence test scores. Using an estimate of general mental ability, or g, based on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, they found SAT scores to be highly correlated with g (r=.82 in their sample, .857 when adjusted for non-linearity) in their sample taken from a 1979 national probability survey. Additionally, they investigated the correlation between SAT results, using the revised and recentered form of the test, and scores on the Raven's Advanced Progressive Matrices, a test of fluid intelligence (reasoning), this time using a non-random sample. They found that the correlation of SAT results with scores on the Raven's Advanced Progressive Matrices was .483, they estimated that this correlation would have been about 0.72 were it not for the restriction of ability range in the sample. They also noted that there appeared to be a ceiling effect on the Raven's scores which may have suppressed the correlation.[140] Beaujean and colleagues (2006) have reached similar conclusions to those reached by Frey and Detterman.[141]

Preparation

SAT preparation is a highly lucrative field.[142] The field was pioneered by Stanley Kaplan, whose SAT preparation course began in 1946 as a 64-hour course.[143] Many companies and organizations offer test preparation in the form of books, classes, online courses, and tutoring.[144] The test preparation industry began almost simultaneously with the introduction of university entrance exams in the U.S. and flourished from the start.[145]

The College Board maintains that the SAT is essentially uncoachable and research by the College Board and the National Association of College Admission Counseling suggests that tutoring courses result in an average increase of about 20 points on the math section and 10 points on the verbal section.[146]

A meta-analysis estimated the effect size to be 0.09 and 0.16 for the verbal and math sections respectively, although there was a large degree of heterogeneity.[147] An earlier meta analysis found similar results and noted "the size of the coaching effect estimated from the matched or randomized studies (10 points) seems too small to be practically important".[148] A systematic literature review estimated a coaching effect of 23 and 32 points for the math and verbal tests, respectively.[145]

Use by high-IQ societies

Certain high IQ societies, like Mensa, the Prometheus Society and the Triple Nine Society, use scores from certain years as one of their admission tests. For instance, the Triple Nine Society accepts scores (verbal and math combined) of 1450 or greater on SAT tests taken before April 1995, and scores of at least 1520 on tests taken between April 1995 and February 2005.[149]

The SAT is sometimes given to students younger than 13 by organizations such as the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth, Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth, Duke TIP, and other organizations who use the results to select, study and mentor students of exceptional ability.

Writing section

In 2005, MIT Writing Director Pavan Sreekireddy plotted essay length versus essay score on the new SAT from released essays and found a high correlation between them. After studying over 50 graded essays, he found that longer essays consistently produced higher scores. In fact, he argues that by simply gauging the length of an essay without reading it, the given score of an essay could likely be determined correctly over 90% of the time. He also discovered that several of these essays were full of factual errors; the College Board does not claim to grade for factual accuracy.

Perelman, along with the National Council of Teachers of English, also criticized the 25-minute writing section of the test for damaging standards of writing teaching in the classroom. They say that writing teachers training their students for the SAT will not focus on revision, depth, accuracy, but will instead produce long, formulaic, and wordy pieces.[150] "You're getting teachers to train students to be bad writers", concluded Perelman.[151]

See also

- ACT (test), a college entrance exam, competitor to the SAT

- College admissions in the United States

- Special Tertiary Admissions Test (STAT), a similar test used in Australia.

- List of admissions tests

- PSAT/NMSQT

- SAT Subject Tests

References

- "2019 SAT Suite of Assessments Annual Report" (PDF). College Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-10-18.

- "Fees And Costs". The College Board. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- "Frequently Asked Questions About ETS". ETS. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "'Massive' breach exposes hundreds of questions for upcoming SAT exams". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Baird, Katherine (2012). Trapped in Mediocrity: Why Our Schools Aren't World-Class and What We Can Do About It. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. "And a separate process that began in 1926 was complete by 1942: the much easier SAT—a test not aligned to any particular curriculum and thus better suited to a nation where high school students did not take a common curriculum—replaced the old college boards as the nations's college entrance exam. This broke the once tight link between academic coursework and college admission, a break that remains to this day."

- Lewin, Tamar (March 5, 2014). "A New SAT Aims to Realign With Schoolwork". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

He said he also wanted to make the test reflect more closely what students did in high school

- "SAT Registration Fees". College Board. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- O'Shaughnessy, Lynn (July 26, 2009). "The Other Side of 'Test Optional'". The New York Times. p. 6. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- Capuzzi Simon, Cecilia (November 1, 2015). "The Test-Optional Surge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Tate, Jeremy (September 23, 2016). "The SAT and ACT Fall Short, But Now There's a Better Alternative". Archived from the original on August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- Balf, Todd (2014-03-06). "The Story Behind the SAT Overhaul". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2017-06-16. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- "SAT Registration". College Board. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2016. "Most students take the SAT spring of junior year or fall of senior year."

- Atkinson, Richard; Geiser, Saul (May 4, 2015). "The Big Problem With the New SAT". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 1, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- "01-249.RD.ResNoteRN-10 collegeboard.com" (PDF). The College Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 6, 2009. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- Geiser, Saul; Studley, Roger (October 29, 2001), UC and the SAT: Predictive Validity and Differential Impact of the SAT I ad SAT II at the University of California (PDF), University of California, Office of the President., archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2016, retrieved September 30, 2014

- Korbin, L. (2006). SAT Program Handbook. A Comprehensive Guide to the SAT Program for School Counselors and Admissions Officers, 1, 33+. Retrieved January 24, 2006, from College Board Preparation Database.

- Atkinson, R.C.; Geiser, S. (2009). "Reflections on a Century of College Admissions Tests". Educational Researcher. 38 (9): 665–76. doi:10.3102/0013189x09351981.

- Honawar, Vaishali; Klein, Alyson (August 30, 2006). "ACT Scores Improve; More on East Coast Taking the SAT's Rival". Education Week. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- Slatalla, Michelle (November 4, 2007). "ACT vs. SAT". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "Colleges and Universities That Do Not Use SAT/ACT Scores for Admitting Substantial Numbers of Students Into Bachelor Degree Programs". fairtest.org. The National Center for Fair & Open Testing. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- Marklein, Mary Beth (March 18, 2007). "All four-year U.S. colleges now accept ACT test". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "The SAT and SAT Subject Tests Educator Guide" (PDF). College Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "SAT Reading Test". College Board. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "SAT Writing and Language Test". College Board. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- "SAT Math Test". The College Board. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- "Score Structure – SAT Suite of Assessments". The College Board. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- "PSAT/NMSQT Understanding Scores 2015 – SAT Suite of Assessments" (PDF). The College Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- "SAT Study Guide for Students – SAT Suite of Assessments". The College Board. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- "SAT Calculator Policy". The College Board. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Scheuneman, Janice; Camara, Wayne. "Calculator Use and the SAT I Math". The College Board. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- "Should graphing calculators be allowed on important tests?" (PDF). Texas Instruments. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- "About The SAT Math Test" (PDF). College Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- "College Board Test Tips". College Board. Archived from the original on November 24, 2009. Retrieved September 9, 2008.

- "SAT Dates And Deadlines". College Board. Archived from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- "SAT International Registration". College Board. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- "Getting SAT Scores". The College Board. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- "Understanding SAT Scores" (PDF). The College Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- "Verifying SAT Scores". The College Board. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- "SAT Percentile Ranks for Males, Females, and Total Group:2006 College-Bound Seniors – Critical Reading + Mathematics" (PDF). College Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- "SAT Percentile Ranks for Males, Females, and Total Group:2006 College-Bound Seniors – Critical Reading + Mathematics + Writing" (PDF). College Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-05-16. Retrieved 2019-05-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Membership Committee (1999). "1998/99 Membership Committee Report". Prometheus Society. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Anderson, Nick SAT scores at lowest level in 10 years, fueling worries about high schools Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine Washington Post. September 4, 2015

- "ACT and SAT® Concordance Tables" (PDF). Research Note 40. College Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 18 Mar 2017.

- "ACT-SAT Concordance Tables" (PDF). ACT, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 18 Mar 2017.

- "Higher Education Concordance Information". College Board. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 18 Mar 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2019-06-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Data (SAT Program Participation And Performance Statistics)". College Entrance Examination Board. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- Lemann, Nicholas (2004). "A History of Admissions Testing". In Zwick, Rebecca (ed.). Rethinking the SAT: The Future of Standardized Testing in University Admissions. New York: RoutledgeFalmer. pp. 5–14.

- Crouse, James; Trusheim, Dale (1988). The Case Against the SAT. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 16–39.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-11-12. Retrieved 2019-11-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hubin, David R. (1988). The SAT – Its Development and Introduction, 1900–1948 (Ph.D.). University of Oregon.

- "G.I Bill History and Timeline". Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- Fuess, Claude (1950). The College Board: Its First Fifty Years. New York: Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- Bennet, Randy Elliot. "What Does It Mean to Be a Nonprofit Educational Measurement Organization in the 21st Century?" (PDF). Educational Testing Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 28 Mar 2015.

- "On Further Examination: Report of the Advisory Panel on the Scholastic Aptitude Test Score Decline" (PDF). College Entrance Examination Board. 1977. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2014.

- "frontline: secrets of the sat: where did the test come from?: the 1901 college board". Secrets of the SAT. Frontline. Archived from the original on May 7, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- Lawrence, Ida; Rigol, Gretchen W.; Van Essen, Thomas; Jackson, Carol A. (2003). "Research Report No. 2003-3: A Historical Perspective on the Content of the SAT" (PDF). College Entrance Examination Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- "frontline: secrets of the sat: where did the test come from?: the 1926 sat". Secrets of the SAT. Frontline. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- Dorans, Neil. "The Recentering of SAT® Scales and Its Effects on Score Distributions and Score Interpretations" (PDF). Research Report No. 2002-11. College Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- Donlon, Thomas; Angoff, William (1971). Angoff, William (ed.). The College Board Admissions Testing Program: A Technical Report on Research and Development Activities Relating to the Scholastic Aptitude Test and Achievement Tests. New York: College Entrance Examination Board. pp. 32–33. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014. Available at the Education Resources Information Center Archived 2014-05-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- Stedman, Lawrence; Kaestle, Carl (1991). "The Great Test Score Decline: A Closer Look". In Kaestle, Carl (ed.). Literacy in the United States. Yale University Press. p. 132.

- Honan, William (March 20, 1994). "Revised and Renamed, S.A.T. Brings Same Old Anxiety". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- DePalma, Anthony (November 1, 1990). "Revisions Adopted in College Entrance Tests". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "Scholastic Assessment Test Score Averages for High-School College-Bound Seniors". National Center for Education Statistics. Archived from the original on May 24, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- The College Handbook, 1985–86. New York: College Entrance Examination Board. 1985. p. 953.

- "Yale University Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT) Scores for Freshmen Matriculants Class of 1980 – Class of 2017". Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- "College-Bound Seniors: 1992 Profile of SAT and Achievement Test Takers". College Entrance Examination Board. 1992. p. 9. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2014. Available at the Education Resources Information Center Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- Barron, James (July 26, 1995). "When Close Is Perfect: Even 4 Errors Can't Prevent Top Score on New S.A.T." The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "SAT I Individual Score Equivalents". College Entrance Examination Board. Archived from the original on September 1, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- The Center for Education Reform (August 22, 1996). "SAT Increase – The Real Story, Part II". Archived from the original on July 21, 2011.

- Stedman, Lawrence (March 2009). "The NAEP Long-Term Trend Assessment: A Review of Its Transformation, Use, and Findings" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Schoenfeld, Jane (May 24, 2002). "College board drops 'score choice' for SAT-II exams". St. Louis Business Journal. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- Zhao, Yilu (June 19, 2002). "Students Protest Plan To Change Test Policy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "College Board To Alter SAT I for 2005–06". Daily Nexus. 20 September 2002. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- Lewin, Tamar (June 23, 2002). "New SAT Writing Test Is Planned". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- "Understanding the New SAT". Inside Higher Ed. 25 May 2005. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- Arenson, Karen (March 10, 2006). "SAT Errors Raise New Qualms About Testing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Arenson, Karen (April 9, 2006). "Class-Action Lawsuit to Be Filed Over SAT Scoring Errors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Hoover, Eric (August 24, 2007). "$2.85-Million Settlement Proposed in Lawsuit Over SAT-Scoring Errors". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- Maslin Nir, Sarah (April 8, 2011). "7,000 Private School Applicants Got Incorrect Scores, Company Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Rimer, Sara (December 30, 2008). "SAT Changes Policy, Opening Rift With Colleges". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- "SAT Score Choice". The College Board. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "Cornell Rejects SAT Score Choice Option". The Cornell Daily Sun. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- "Standardized Testing Requirements". Cornell University. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- "Testing". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- "Freshman Application Requirements: Standardized Testing". Stanford University. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- "Standardized Testing Requirements & Policies". Yale University. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- "SAT® Score-Use Practices by Participating Institution" (PDF). The College Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2009. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- Anderson, Jenny (March 27, 2012). "SAT and ACT to Tighten Rules After Cheating Scandal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- "Test Security and Fairness". The College Board. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- Lewin, Tamar (March 5, 2014). "A New SAT Aims to Realign With Schoolwork". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- "New, Reading-Heavy SAT Has Students Worried". The New York Times. February 8, 2016. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- "Key shifts of the SAT redesign". The Washington Post. March 5, 2014. Archived from the original on May 15, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- "SAT FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions". College Board. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- Commission on New Possibilities for the Admissions Testing Program (1990). Beyond Prediction. College Entrance Examination Board. p. 9.

- Pitsch, Mark (November 7, 1990). "S.A.T. Revisions Will Be Included In Spring '94 Test". Education Week.

- Jordan, Mary (March 27, 1993). "SAT Changes Name, But It Won't Score 1,600 With Critics". Washington Post.

- Horwitz, Sari (May 5, 1995). "Perfectly Happy With Her SAT; D.C. Junior Aces Scholastic Assessment Test With a 1,600". Washington Post.