Rose water

Rose water is a flavoured water made by steeping rose petals in water. Additionally, it is the hydrosol portion of the distillate of rose petals, a by-product of the production of rose oil for use in perfume. It is used to flavour food, as a component in some cosmetic and medical preparations, and for religious purposes throughout Europe and Asia.

| |

| Type | Flavoured water |

|---|---|

| Region or state | Europe and Asia |

| Main ingredients | Rose petals |

| Ingredients generally used | Water |

Rose syrup (not to be confused with rose hip syrup) is a syrup made from rose water, with sugar added, and is an Ark of Taste endangered food.[1] Gulkand in South Asia,[2] is a syrupy mashed rose mixture.

History

Since ancient times, roses have been used medicinally, nutritionally, and as a source of perfume. The ancient Greeks, Romans and Phoenicians considered large public rose gardens to be as important as croplands such as orchards and wheat fields.[3]

Rose perfumes are made from rose oil, also called attar of roses, which is a mixture of volatile essential oils obtained by steam-distilling the crushed petals of roses. Rose water is a by-product of this process.[4] The cultivation of various fragrant flowers for obtaining perfumes, including rose water, may date back to Sassanid Persia,[5] where it was known as golāb (Middle Persian: گلاب), from gul (rose) and ab (water). The term was adopted into Byzantine Greek as zoulápin.[6] The process of creating rose water through steam distillation was refined by Persian and Arab chemists in the medieval Islamic world which led to more efficient and economic uses for perfumery industries.[7]

Uses

Edible

It is sometimes added to lemonade, and often added to water to mask unpleasant odours and flavours found in tap water.

In South Asian cuisine, rose water is a common ingredient in sweets such as laddu, gulab jamun, and peda;[2] and is also used to flavour milk, lassi, rice pudding, and other dairy dishes.

In Malaysia and Singapore, sweet red-tinted rose water is mixed with milk, making a sweet pink drink called bandung.

American and European bakers often used rose water until the 19th century, when vanilla became popular. It is used in Waverly Jumbles. In Yorkshire, rose water has long been used as a flavouring for the regional specialty, Yorkshire curd tart. In Iran, it is added to tea, ice cream, cookies, and other sweets in small quantities.

In Middle Eastern cuisines, rosewater is used heavily in many dishes, especially in sweets such as nougat, gumdrops, baklava, and Turkish delight (Rahat lokum). Marzipan has long been flavoured with rose water.[8] In Cyprus, Mahaleb's Cypriot version known as μαχαλεπί, uses rose water (ροδόσταγμα). Rose water is frequently used as a halal substitute for red wine and other alcohols in cooking. The Premier League offer a rose water-based beverage as an alternative for champagne when awarding Muslim players.[9] In accordance with the ban on alcohol consumption in Islamic countries, rose water is used instead of champagne on the podium of the Bahrain Grand Prix and Abu Dhabi Grand Prix.[10]

Cosmetic and medicinal use

In medieval Europe, rose water was used to wash hands at a meal table during feasts.[11] Rose water is a usual component of perfume.[12] A rose water ointment is occasionally used as an emollient, and rose water is sometimes used in cosmetics such as cold creams, toners and face wash.[12] Its anti-inflammatory properties make it a good tool against skin disorders such as Rosacea and eczema.[12]

Some people in India also use rose water as a spray applied directly to the face as a perfume and moisturizer, especially during the winter; it is often sprinkled in Indian weddings to welcome guests.

Religious uses

Rose water is used in the religious ceremonies of Hinduism,[2] Islam,[2] Christianity—particularly in the Eastern Orthodox Church—Zoroastrianism, and Baha'i Faith (in Kitab-i-Aqdas 1:76).

Composition

Depending on the origin and manufacturing method, rose water is obtained from the sepals and petals of Rosa × damascena through steam distillation. The following monoterpenoid and alkane components can be identified with gas chromatography: mostly citronellol, nonadecane, geraniol and phenyl ethyl alcohol, and also henicosane, 9-nonadecen, eicosane, linalool, citronellyl acetate, methyleugenol, heptadecane, pentadecane, docosane, nerol, disiloxane, octadecane, and pentacosane. Usually, phenylethyl alcohol is responsible for the typical odour of rose water but is not always present in rose water products.[13]

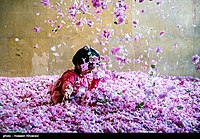

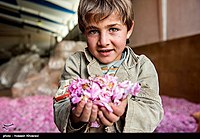

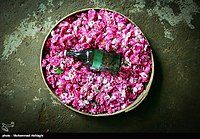

Images

See also

References

- https://www.fondazioneslowfood.com/en/slow-food-presidia/rose-syrup/

- KRISHNA GOPAL DUBEY. "HE INDIAN CUISINE".

- "The rose in Ancient times". Rosense.uk.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2004-01-01). Food in Medieval Times. p. 29. ISBN 9780313321474.

- Marks, Gil (17 November 2010). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. HMH. ISBN 9780544186316 – via Google Books.

- Shahbazi, S. (1990). BYZANTINE-IRANIAN RELATIONS. In Encyclopædia Iranica (Vol. IV, pp. 588-599).

- Ahmad Y Hassan, Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part III: Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- Adamson, Melitta Weiss (2004-01-01). Food in Medieval Times. p. 89. ISBN 9780313321474.

- "PL offers 'rosewater and pomegranate' drink instead of champagne to avoid offending Muslim players". Yahoo! News. 26 August 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Agency, Reuters News (2017-07-30). "Champagne to be sprayed on the F1 podium again after two years of sparkling wine". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- Food in Medieval Times By Melitta Weiss Adamson

- "Rose water: Benefits, uses, and side effects". Medical News Today. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- Loghmani-Khouzani H, Fini Sabzi O, Safari J H (2007). "Essential Oil Composition of Rosa damascena". Scientia Iranica 14 (4), pp 316–319. Sharif University of Technology, Research Note Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Look up rose water in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rose water. |

.jpg)