Public school (United Kingdom)

A public school in England and Wales is a fee-charging endowed school originally for older boys which was "public" in the sense of being open to pupils irrespective of locality, denomination or paternal trade or profession. The term was formalised by the Public Schools Act 1868,[1][2] which put into law most recommendations of the 1864 Clarendon Report. Nine prestigious schools were considered by Clarendon, and seven subsequently included in the Act.

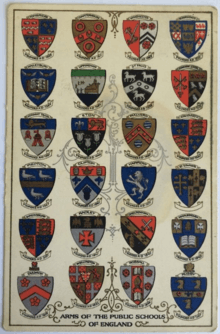

These were boys' boarding schools, but some are now mixed and some accept day pupils as well as boarders. By the 1930s, the term "public school" applied to at least twenty-four schools,[3] although a wider informal definition has also been applied since the 19th century.

Public schools have had a strong association with the ruling classes.[4] Historically, the sons of officers and senior administrators of the British Empire were educated in England while their fathers were on overseas postings. In 2019, two thirds of Cabinet Ministers had been educated at fee-charging schools, although most prime ministers since 1964 were educated at state schools.[5]

Definition

There is no single or absolute definition of a public school, and the use of the term has varied according to context.[6] Public schools are not funded from public taxes. The independent schools’ representative body, the Independent Schools Information Service (ISIS)[7][8] defined public schools as long-established, student-selective, fee-charging independent secondary schools that cater primarily for children aged between 11 or 13 and 18, and whose head teacher is a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference (HMC).[9]

The above definition of 1981 has resonance with that of Sydney Smith written in 1810 in The Edinburgh Review. "By a public school, we mean an endowed place of education of old standing, to which the sons of gentlemen resort in considerable numbers, and where they continue to reside, from eight or nine, to eighteen years of age. We do not give this as a definition which would have satisfied Porphyry or Duns-Scotus, but as one sufficiently accurate for our purpose. The characteristic features of these schools are, their antiquity, the numbers, and the ages of the young people who are educated at them ...".[10]

A public school has been very simply defined as "a non-local endowed boarding school for the upper classes".[11]

In November 1965, the UK Cabinet considered the definition of a public school for the purpose of the Public Schools Commission set up that year. It started with the 1944 Fleming Committee definition of Public Schools, which consisted of schools which were members of the then Headmasters' Conference or the Girls' Schools Association. At that time, there were 276 such independent schools, which the 1965 Public Schools Commission took in scope of its work and also considered 22 maintained and 152 direct grant grammar schools.[12]

In 2020, using the 1981 ISIS definition or the 1944 Fleming Committee definition, there are 296 independent (and mainly boys') secondary schools belonging to the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference,[13] and 230 independent girls' secondary schools belonging to the Girls' Schools Association.

The majority of public schools are affiliated with, or were established by, a Christian denomination, principally the Church of England, but in some cases the Roman Catholic and Methodist churches; or else identify themselves as "non-denominational Christian". A small number are inherently secular, most notably Oswestry School.[14]

History

Public schools emerged from charity schools established to educate poor scholars—public because access to them was not restricted on the basis of religion, occupation, or home location, and that they were subject to public management or control,[15] in contrast to private schools which were run for the personal profit of the proprietors.[16] The origins of schools in the UK were primarily religious, although in 1640 the House of Commons invited Comenius to England to establish and participate in an agency for the promotion of learning. It was intended that by-products of this would be the publication of 'universal' books and the setting up of schools for boys and girls.[17]

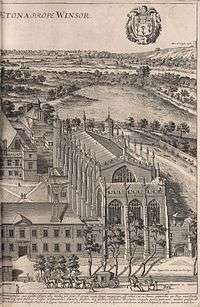

Soon after the Clarendon Commission reported in 1864, the Public Schools Act 1868 gave the following seven schools independence from direct jurisdiction or responsibility of the Crown, the established church, or the government: Charterhouse, Eton College, Harrow School, Rugby School, Shrewsbury School, Westminster School, and Winchester College. Henceforth each of these schools was to be managed by a board of governors. The following year, the headmaster of Uppingham School invited thirty-seven of his fellow headmasters[18] to form what became the Headmasters' Conference – later the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference.

Until the late medieval period most schools were controlled by the church; and had specific entrance criteria; others were restricted to the sons of members of guilds, trades or livery companies. From the 16th century onward, boys' boarding schools were founded or endowed for public use.[19] Historically, most of these public schools were all-boys and full boarding. Some schools are particularly old, such as The King's School, Canterbury (founded 597), The King's School, Rochester (founded 604), St Peter's School, York (founded c. 627), Sherborne School (founded c. 710, refounded 1550 by Edward VI), Warwick School (c. 914), The King's School, Ely (c. 970) and St Albans School (948).

In 1816 Rudolph Ackerman published a book which used the term "History of the Public Schools" of what he described as the "principal schools of England",[20] entitled The History of the Colleges of Winchester, Eton, and Westminster; with the Charter-House, the Schools of St. Paul's, Merchant Taylors, Harrow, and Rugby, and the Free-School of Christ's Hospital.

Separate preparatory schools (or "prep schools") for younger boys developed from the 1830s, with entry to the senior schools becoming limited to boys of at least 12 or 13 years old. The first of these was Windlesham House School, established with support from Thomas Arnold, headmaster of Rugby School.[21][22]

Many of the public schools, including Rugby School, Harrow School and The Perse School, fell into decline during the 18th century and nearly closed in the early 19th century. Protests in the local newspaper forced governors of The Perse School to keep it open, and a court case in 1837 required reform of the abuse of the school's charitable trust.[23]

Victorian period

A Royal Commission, the Clarendon Commission (1861–1864), investigated nine of the more established schools, including seven boarding schools (Charterhouse, Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Shrewsbury, Westminster and Winchester) and two day schools (St Paul's and the Merchant Taylors').[3]

Howard Staunton's book of 1865 entitled The Great Schools of England[24] considered those nine schools plus Cheltenham College, Christ's Hospital, and Dulwich College.

The Public Schools Act 1868 subsequently regulated and reformed seven public schools defined in that Act, and in summary established and granted autonomy to new governing bodies for the seven schools and as part of that, released them from previous obligations under their founding charters to educate "boys on the Foundation" ie scholarship boys who paid nominal or no fees.[25] St Paul's School and the Merchant Taylors' School claimed successfully that their constitutions made them "private" schools, and were excluded from the requirements of this legislation.[26] In 1887 the Divisional Court and the Court of Appeal determined that the City of London School was a public school.[27]

The Taunton Commission was appointed in 1864 to examine the remaining 782 endowed grammar schools, and in 1868 produced recommendations to restructure their endowments; these recommendations were included, in modified form, in the Endowed Schools Act 1869. In that year Edward Thring, headmaster of Uppingham School, wrote to 37 of his fellow headmasters of what he considered the leading boys' schools, not covered by the Public Schools Act of 1868, inviting them to meet annually[28] to address the threat posed by the Endowed Schools Act of 1869. In the first year 12 headmasters attended; the following year 34 attended, including heads from the Clarendon schools. The Headmasters' Conference (HMC), now the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference, has grown steadily and by 2020 had 296 British and Irish schools as members.[29]

The Public Schools Yearbook was published for the first time in 1889, listing 30 schools, mostly boarding schools. The day school exceptions were St Paul's School and Merchant Taylors' School. Some academically successful grammar schools were added in later editions. The 1902 edition included all schools whose principals qualified for membership of the Headmasters' Conference.[30]

In 1893 Edward Arnold published a book entitled Great Public Schools with a chapter on each of Eton, Harrow, Charterhouse, Cheltenham, Rugby, Clifton, Westminster, Marlborough, Haileybury, and Winchester.[31]

The Bryce Report of 1895 (i.e. Report of the Royal Commission on Secondary Education) described the schools mentioned in the 1868 Act as the "seven 'great public schools'".[32]

20th century

- 2. Haileybury

- Uppingham

- St Paul's

- Manchester Grammar

- 3. Merchant Taylors'

- Eton

- Malvern

- King Edward VI

The Fleming Report (1944) entitled The Public Schools and the General Education System defined a public school as a member of the Governing Bodies Association or the Headmasters' Conference.[33] The Fleming Committee recommended that one-quarter of the places at the public schools should be assigned to a national bursary scheme for children who would benefit from boarding. A key advocate was the post-war Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson, but it never got into legislation in that age of severe budget constraints. The Conservative government elected in 1951 did not adopt the proposal. It failed because it was not a high priority for either party, money was tight, there was wavering support from both public schools and local education authorities, and no consensus was reached on how to select the pupils to participate.[34]

Based on the recommendations of the Fleming Report, the Education Act 1944 "the Butler Act" did offer a new status to endowed grammar schools receiving a grant from central government. The direct grant grammar schools would henceforth receive partial state funding (a "direct grant") in return for taking between 25 and 50 percent of its pupils from state primary schools.[35] Other grammar schools were funded by Local Education Authorities.

The Labour government in 1965 made major changes to the organisation of maintained schools, directing local authorities to phase out selection at eleven. It also fulfilled its pledge to examine the role of public schools, setting up a Royal commission "to advise on the best way of integrating the public schools with the State system". The commission used a wider definition than that of the Fleming Committee.[12] The Public Schools Commission produced two reports: the Newsom Report of 1968 entitled The Public Schools Commission: First Report covering boarding schools and the Donnison Report of 1970 entitled The Public Schools Commission: Second Report covering day schools, including also direct grant and maintained grammar schools.

| Type | Total schools |

No. of pupils |

Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boarding | Day | Boarding | Day | |||

| Independent schools within the HMC, GBA or GSA | 276 | 95,500 | 106 | 28 | 83 | 59 |

| Direct grant maintained schools within the HMC (out of the total 179 grant maintained schools) In addition there were 27 Direct Grant schools which are not within the HMC. | 152 | 14 | 58 | 1 | 79 | |

| Maintained schools within the HMC | 22 | |||||

| State secondary schools (maintained) | 6000 | |||||

| Private schools | 3130 | |||||

| Source: HMG [12] | ||||||

Late 20th century

The direct grant scheme was abolished in 1975 and the HMC schools within the scheme became fully independent.[36] Local authorities were ordered to cease funding places at independent schools. This accounted for over quarter of places at 56 schools, and over half the places at 22 schools.[37] Between 1975 and 1983 funding was withdrawn from 11 voluntary-aided grammar schools, which became independent schools and full members of the HMC.[lower-alpha 1] The loss of state-funded places, coinciding with the recession, put them under severe financial strain, and many became co-educational in order to survive.[36] A direct grant was partially revived between 1981 and 1997 with the Assisted Places Scheme, providing support for 80,000 pupils attending private and independent schools.[41]

Many boarding schools started to admit day pupils for the first time, and others abolished boarding completely.[42][43] Some started accepting girls in the sixth form, while others became fully co-educational.[44]

The 1968 film if...., which satirised the worst elements of English public school life, culminating in scenes of armed insurrection, won the Palme d'Or at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival.[45][46] These actions were felt in British public schools; the new headmaster at Oundle School noted that "student protests and intellectual ferment were challenging the status quo".[47] These challenges coincided with the mid-1970s recession and moves by the Labour government to separate more clearly the independent and state sectors.[36]

Corporal punishment, was abolished in state schools in 1986, and had been abandoned in most public schools by the time it was formally banned in independent schools in 1999 in England and Wales,[48] (2000 in Scotland and 2003 in Northern Ireland).[49] The system of fagging, whereby younger pupils were required to act to some extent as personal servants to the most senior boys, was phased out during the 1970s and 1980s.[50]

More than half of HMC schools are now either partially or fully co-educational.[51] Of the Clarendon nine, two are fully co-educational (Rugby and Shrewsbury), two admit girls to the sixth form only (Charterhouse and Westminster), two remain as boys-only day schools (St Paul's[52] and Merchant Taylors') and three retain the full-boarding, boys-only tradition (Eton, Harrow and Winchester).

Associations with the ruling class

Former Harrow pupil Stanley Baldwin wrote that when he first became Prime Minister in 1923, he wanted to have six Harrovians in his government. "To make a cabinet is like making a jig-saw puzzle fit, and I managed to make my six fit by keeping the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer for myself".[53] Until the war, the role of public schools in preparing pupils for the gentlemanly elite meant that such education, particularly in its classical focus and social mannerism, became a mark of the ruling class.

For three hundred years, the officers and senior administrators of the British Empire sent their sons back home to boarding schools for education as gentlemen. This was often for uninterrupted periods of a year or more. The 19th-century public school ethos promoted ideas of service to Crown and Empire, exemplified in familiar tropes such as "Play up! Play up! And play the game!" from Henry Newbolt's poem Vitaï Lampada and "the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton", the latter popularly attributed to the Duke of Wellington. Many ex-pupils, like those from other schools, had, and still have, a nostalgic affection for their old schools (George Orwell remembered being "interested and happy" at Eton,[54]) and a public school tie and an "old boy network" of former pupils were useful in advancing a career. The English public school model influenced the 19th-century development of Scottish elite schools, but a tradition of the gentry sharing their primary education with their tenants kept Scotland more egalitarian.[55][56]

Acceptance of social elitism was reduced by the two world wars,[57] but despite portrayals of the products of public schools as "silly asses" and "toffs", the old system continued well into the 1960s. This was reflected in contemporary popular fiction such as Len Deighton's The IPCRESS File, which had a sub-text of supposed tension between the grammar school educated protagonist and the public school background of his more senior but inept colleague.

Postwar social change has, however, gradually been reflected across Britain's educational system, while at the same time fears of problems with state education have pushed some parents, who can afford the fees or whose pupils qualify for bursaries or scholarships, towards public schools and other schools in the independent sector. By 2009 typical fees were up to £30,000 per annum for boarders.[58] As of Boris Johnson, 20 Prime Ministers have attended Eton,[59] seven Harrow, and six Westminster. Between 2010 and 2016, Prime Minister David Cameron (Eton) and Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne (St Paul's) had both been educated at Clarendon schools.[60]

Conservative former cabinet minister Iain Macleod wrote in 1964 in "The Tory Leadership" that an conspiracy by an Etonian "magic circle" had made Alec Douglas-Home prime minister. The assertion was so powerful that until Cameron, being an Etonian was a disadvantage to becoming a party leader, as Douglas Hurd learned in the 1990 Conservative Party leadership election.[61] While Home had been educated at Eton and the incoming Labour Prime Minister in 1997 (Tony Blair) at Fettes College, all six British Prime Ministers in office between 1964 and 1997 and from 2007 to 2010 were educated at state schools (Harold Wilson, Edward Heath, Margaret Thatcher, and John Major at grammar schools, and James Callaghan and Gordon Brown at other state secondary schools).[62][63] Theresa May's secondary school education also was primarily in the state sector.

While members of the aristocracy and landed gentry no longer dominate independent schools, studies have shown that such schools still retain a degree of influence over the country's professional and social elite despite educating less than 10% of the population. A 2012 study published by the Sutton Trust noted that 44% of the 7,637 individuals examined whose names appeared in the birthday lists of The Times, The Sunday Times, The Independent or The Independent on Sunday during 2011 – across all sectors, including politics, business, the arts and the armed forces – were educated at independent schools.[64] It also found that 10 elite fee-paying schools (specifically Eton, Winchester, Charterhouse, Rugby, Westminster, Marlborough, Dulwich, Harrow, St Paul's, and Wellington[64]) produced 12% of the leading high-flyers examined in the study.[65] The Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission came to a similar conclusion in a 2014 study of the professions: 71% of senior judges, 62% of senior armed forces officers, 55% of Whitehall permanent secretaries and 50% of members of the House of Lords had been privately educated.[66]

Public schools (especially boarding schools) have been light-heartedly compared by their pupils or ex-pupils to prisons. O. G. S. Crawford stated that he had been "far less unhappy" when incarcerated in Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp during the First World War than he had previously been at his public school, Marlborough College.[67] Evelyn Waugh observed in his satirical novel Decline and Fall (1928) that "anyone who has been to an English public school will always feel comparatively at home in prison".[68] Former Cabinet Minister Jonathan Aitken, sentenced to 18 months' imprisonment for perjury in 1999, commented in an interview: "As far as the physical miseries go, I am sure I will cope. I lived at Eton in the 1950s and I know all about life in uncomfortable quarters."[69]

Minor public schools

The term minor public school is subjective. While the nine Clarendon schools are clearly major (a term rarely used), between the wars, there was in place a continuum of boarding schools, most of which would have been considered 'minor'. Public school rivalry[70] is a factor in the perception of a 'great' or 'major' versus 'minor' distinction.[71]

Literature and media

Rugby School inspired a whole new genre of literature, i.e. the school story. Thomas Hughes's Tom Brown's School Days, a book published in 1857 was set there. There were as many as 90 stories set in British boarding schools, taking as an example just girls' school stories,[72] published between Sarah Fielding's 1749 The Governess, or The Little Female Academy and the 1857 Tom Brown's School Days. Such stories were set in a variety of institutions including private boarding and prep schools as well as public schools. Tom Brown's School Days' influence on the genre of British school novels includes the fictional boarding schools of Rudyard Kipling's Stalky & Co. at "the College" (based on the United Services College), Frank Richards' Billy Bunter at Greyfriars School, James Hilton's Mr Chips at Brookfield,[lower-alpha 2] Anthony Buckeridge's Jennings at Linbury Court, P. G. Wodehouse's St. Austin's and girls' schools Malory Towers and St. Trinian's. It also directly inspired J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series, set at the fictional boarding school Hogwarts. The series' first novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone has many direct parallels in structure and theme to Tom Brown's School Days.[73]

Alan Bennett, used the metaphor of an end of term revue at a minor public school to contrast the events of the twentieth century with that of public school life, in his 1968 play Forty Years On. The title alludes to the Harrow school song, Forty Years On.[74]

See also

- Rugby Group, a group of eighteen schools within the HMC

- Eton Group, a group of twelve schools within the HMC

- List of the oldest schools in the United Kingdom (a number of which are public schools)

- List of Victoria Crosses by school

- Public Schools Battalions

- Combined Cadet Force

- List of SR V "Schools" class locomotives (named principally after public schools)

- Fagging

- Public Schools Club

- Private school

- List of independent schools in the United Kingdom

Notes

- There were 13 such schools,[38][39][40] but two were girls' schools, and thus ineligible for HMC membership.

- reputed to be The Leys School

References

- The 1868 Act does not define "public school"; as made clear in its preamble, it is "An Act to make further Provision for the good Government and Extension of certain Public Schools in England."

- "Text of the Public Schools Act 1868". www.educationengland.org.uk.

- Shrosbree (1988), p. 12.

- Green, Francis; Kynaston, David (2019). Engines of privilege : Britain's private school problem. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-5266-0127-8. OCLC 1108696740.

- "Article on 2019 UK Cabinet". The Guardian. 25 July 2019.

- "Discussion on the term 'Public School' Appendix A of Fleming Report (1944)". educationengland.org.uk. Gillard D (2018) Education in England: a history.

- Dictionary of British Education. "Google Books".

- "Independent Schools Council".

- Independent Schools: The Facts, Independent Schools Information Service, 1981,

- "The Edinburgh Review". Google Books.

- Mack, Edward C. (1938). Public Schools and British Opinion, 1780 to 1860. London: Methuen. p. viii.

- Public Schools: Memorandum by the Sectary of State for Education and Science (PDF), 19 November 1965, p. 1

- "'Fact 2' from HMC 'Facts and Figures'".

- Leach, A. F. "Grammar Schools of Medieval England". Google Books.

- "public school, n. and adj.". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 March 2014. (subscription required)

- "private school n.". at private adj.1, adv., and n. Special uses 2. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 March 2014. (subscription required)

- "Education in England – Chapter 1". www.educationengland.org.uk.

- "The Public and Preparatory Schools Handbook 1968". Google Books.

- Oxford English Dictionary, June 2010.

- "The History of the Colleges of Winchester, Eton, and Westminster: With the Charter House, the Schools of St. Paul's, Merchant Taylors, Harrow, and Rugby, and the Free-school of Christ's Hospital". Google Books.

- "The History of Windlesham House School" (PDF). Windlesham House School. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- "History of British Preparatory School".

- "History – Almost 400 years old". The Perse School.

- Staunton, Howard (1865). The Great Schools of England. Milton House, Ludgate Hill: Sampson Low, Son, and Marston. ISBN 978-1345096538.

- "Text of Public Schools Act 1868". Gillard D (2018) Education in England: a history.

- Shrosbree (1988), p. 118.

- Blake v The Mayor and Citizens of the City of London [1887] L.R. 19 Q.B.D. 79.

- "The Public and Preparatory Schools Handbook 1968". Google Books.

- "Member schools in British Isles". About Us - HMC.

- Honey (1977), pp. 250–251.

- Various Authors (1893). Great Public Schools. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0530527772.

- "Page 41 Bryce Report 1895". www.educationengland.org.uk/history. Gillard D. (2018) Education in England: a history.

- Fleming (1944), p. 1.

- Nicholas Hillman, "Public schools and the Fleming report of 1944: shunting the first-class carriage on to an immense siding?." History of Education 41#2 (2012): 235–255.

- Donnison (1970), p. 49.

- Walford (1986), p. 149.

- Donnison (1970), pp. 81, 91.

- Dr Rhodes Boyson, Under-Secretary of State for Education (2 July 1979). "Schools (Reorganisation)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. col. 486W.

- Dr. Rhodes Boyson, Under-Secretary of State for Education (5 November 1980). "Schools (Status)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. col. 579W.

- Mr Clement Freud, MP for Isle of Ely (29 January 1981). "Education (Cambridgeshire)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. col. 1151.

- "The main elements of the Queen's Speech on May 14, 1997 upon the two Education Bills". BBC Politics 1997. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- Sampson (1971), p. 132.

- Walford (1986), p. 244.

- Walford (1986), pp. 141–144.

- "Festival de Cannes: If..." festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- "If... (1968) film review". BBC. 26 February 2002.

if... "taps into the revolutionary spirit of the late 60s. Each frame burns with an anger that can only be satisfied by imagining the apocalyptic overthrow of everything that middle class Britain holds dear

- "Headmaster Dr Barry Trapnell CBE (1924–2012)". Oundle School. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- "Corporal punishment banned for all". BBC News.

- "Corporal punishment in schools – United Kingdom".

- Walford (1989), pp. 82–83.

- Walford (1986), pp. 141–142.

- St Paul's admits a small number of boarders.

- Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 286.

- Buddicom, Jacintha. Eric and Us. Finlay Publisher. 2006: p. 58

- P.J. Cain; A. G. Hopkins (2016). British Imperialism: 1688–2015. Routledge. p. 724.

- Peter W. Cookson and Caroline H. Persell, "English and American residential secondary schools: A comparative study of the reproduction of social elites." Comparative Education Review 29#3 (1985): 283–298. in JSTOR

- Marwick, A. "Britain and the Netherlands". Springer.

- "ISC Annual Census 2009". Independent Schools Council. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 6 December 2009.

- Glancy, Josh (11 January 2020). "British Elites Know Who Isn't Quite Their Type". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- The Educational Backgrounds of Government Ministers in 2010 Sutton Trust, 2010.

- Vernon Bogdanor (18 January 2014). "The Spectator book review that brought down Macmillan's government". The Spectator. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- "How politics got 'posh' again". The Daily Telegraph. 23 January 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Resignations fuel fears of posh-boy politics". The New Zealand Herald. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "The Educational Backgrounds of the Nation's Leading People" (PDF). Sutton Trust. November 2012.

- "Public schools retain grip on Britain's elite". The Daily Telegraph. 20 November 2012.

- Arnett, George (28 August 2014). "Elitism in Britain – breakdown by profession". The Guardian.

- Crawford, O.G.S. (1955). Said and Done: the Autobiography of an Archaeologist. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 26, 142–3.

- Waugh, Evelyn (1937) [1928]. Decline and Fall. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 188. (Part 3, Chapter 4)

- "Jonathan Aitken quotes". izquotes.com. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- Mount, Harry (12 April 2019). "A guide to public school rivalries". The Spectator.

- Delingpole, James (17 December 2011). "Thank God I don't have that ghastly sense of entitlement that Eton instils". The Spectator.

- Gosling, Juliet (1998). "5". Virtual Worlds of Girls. University of Kent at Canterbury.

- Steege, David K. "Harry Potter, Tom Brown, and the British School Story". The Ivory Tower and Harry Potter: Perspectives on a Literary Phenomenon: 141–156.

- Spencer, Charles (18 May 2004). "School's back with Bennett at his best". The Telegraph. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

Further reading

- Allsobrook, D. I. (1973) "The reform of the endowed schools: the work of the Northamptonshire Educational Society, 1854–1874", History of Education 2#1 pp 35–55.

- Bamford, T.W. (1967) The Rise of the Public Schools: A Study of boys’ Public Boarding Schools in England and Wales from 1837 to the Present Day.

- Benson, A. C. (2011) [1902]. The Schoolmaster: A Commentary Upon the Aims and Methods of an Assistant-master in a Public School. Peridot Press. ISBN 978-1-908095-30-5.

- Bishop, T.J.H. and Wilkinson, R. (1967) Winchester and the Public School Élite: A Statistical Analysis.

- Brooke-Smith, James (2019). Gilded Youth: Privilege, Rebellion and the British Public School. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1789140668.

- Carman, Dominic (2013). Heads Up: the challenges facing England's leading head teachers. London, UK: Thistle Publishing. ISBN 978-1909869301.

- Dishon, Gideon. (2017) "Games of character: team sports, games, and character development in Victorian public schools, 1850–1900." Paedagogica Historica: 1–17 https://www.researchgate.net

- Fleming, David, ed. (1944), Report on the Public Schools and the General Educational System, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office

- Gardner, Brian.(1973) The Public Schools: An Historical Survey Hamish Hamilton, London ISBN 978-0241023372

- Green, Francis (2019). Engines of Privilege: Britain's Private School Problem. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1526601261.

- Honey, John Raymond de Symons (1977), Tom Brown's universe: the development of the Victorian public school, Quadrangle/New York Times Book Co., ISBN 978-0-8129-0689-9

- Hope-Simpson, J. B. (1967) Rugby since Arnold: A History of Rugby School from 1842 (1967)

- Lunn, Arnold (1913). The Harrovians A Tale of Public School Life. ISBN 978-1453809488.

- Jones, Henry Paul Mainwaring (1918). "War Letters of a Public-School Boy". Project Gutenberg.

- Kandel, Isaac Leon (1930), History of Secondary Education: a study in the development of liberal education, Houghton Mifflin

- Mack, Edward Clarence (1938), Public Schools and British Opinion, 1780 to 1860: the relationship between contemporary ideas and the evolution of an English institution, New York: Columbia University Press [Covers history and reputation of Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Shrewsbury, Westminster, Winchester, and Charterhouse.]

- Mack, Edward Clarence (1941). Public Schools and British Opinion since 1860: the relationship between contemporary ideas and the evolution of an English institution. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mangan, J.A. (2009). Athleticism in the Victorian and Edwardian Public School: The Emergence and Consolidation of an Educational Ideology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521090391.

- Nicolson, Harold (1956), Good Behaviour – being a study of certain types of civility, Garden City, NY: Doubleday

- Ogilvie, Vivian (1957), The English Public School, London: Batsford

- Onyeama, Dillibe (1972). Nigger at Eton. ISBN 978-9782335920.

- Peel, Mark (2015). The New Meritocracy: A History of UK Independent Schools 1979-2014. Elliott & Thompson Limited. ISBN 978-1783961757.

- Reed, John R. (1964) Old school ties; the public schools in British literature online

- Renton, Alex (2018). Stiff Upper Lip: Secrets, Crimes and the Schooling of a Ruling Class. W&N. ISBN 978-1474601016.

- Roach, John (2012), Secondary Education in England 1870–1902: Public Activity and Private Enterprise, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-96008-8 online at Questia

- Rodgers, John (1938). The Old Public Schools of England. B. T. Batsford, Limited.

- Sampson, Anthony (1971), The New Anatomy of Britain, London: Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 978-0-340-14751-1

- Seldon, Anthony (2013). Public Schools and the Great War: The Generation Lost. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1781593080.

- Shrosbree, Colin (1988), Public Schools and Private Education: The Clarendon Commission, 1861–64, and the Public Schools Acts, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-2580-8

- Simon, B. and Bradley, I., eds. (1975) The Victorian Public School: Studies in the Development of an Educational Institution ISBN 978-0717107407

- Stephen, Martin (2018). The English Public School - A Personal and Irreverent History. Metro Publishing. ISBN 978-1786068774.

- Turner, David (2015). The Old Boy: The Decline and Rise of the Public School. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300189926.

- Verkaik, Robert (2018). Posh Boys: How The English Public Schools Run Britain. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1786073839.

- Walford, Geoffrey (1986), Life in Public Schools, London: Methuen, ISBN 978-0-416-37180-2

- —— (1989), "Bullying in public schools: myth and reality", in Tattum, Delwyin P.; Lane, David A. (eds.), Bullying in Schools, Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books, pp. 81–88, ISBN 978-0-948080-22-7

- Walker, T. A. (1907–21), "Chapter XV. English and Scottish Education. Universities and Public Schools to the Time of Colet", in Ward, A. W.; Waller, A. R. (eds.), Volume II: English. The End of the Middle Ages, The Cambridge History of English and American Literature

- Warner, Rex (1945). English Public Schools. London: William Collins.

- Waugh, Alec (1917). The Loom of Youth. ISBN 978-1448200528.

- Wilkinson, R. (1964) The Prefects: British Leadership and the Public School Tradition: A Comparative Study in the Making of Rulers

Primary sources

- Donnison, David, ed. (1970), Report on Independent Day Schools and Direct Grant Grammar Schools, Public Schools Commission, Second Report, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, ISBN 978-0-11-270170-5.

- Newsom, John, ed. (1963), Half Our Future, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Spens, Will, ed. (1938), Secondary education with special reference to grammar schools and technical high schools, London: HM Stationery Office, retrieved 23 April 2013.

External links

- Archive Administrator (9 March 2010). "OFT issues statement of objections against 50 independent schools". The Office of Fair Trading. Retrieved 26 May 2019.