Podokesaurus

Podokesaurus ("swift-footed lizard") was a small carnivorous dinosaur that lived during the Pliensbachian–Toarcian stages of the Early Jurassic Period, and as such is one of the earliest known dinosaurs to inhabit the eastern United States.

| Podokesaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

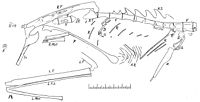

| Holotype specimen, with tail and skull bones at left, and body at right | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Coelophysoidea |

| Genus: | †Podokesaurus Talbot, 1911 |

| Species: | †P. holyokensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Podokesaurus holyokensis Talbot, 1911 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Discovery

In 1910, the American geologist Mignon Talbot was walking with her sister Ellen to Holyoke, Massachusetts, when they passd a farm and notied a small hill nearby. It had a gravel pit at one side, and was formed by an accumulation of sand, gravel, and boulders left by a receding glacier. Talbot noticed a white streak on a sandstone boulder at the bottom of the gravel pit, and upon discovering these were bones, she told her sister she had found a "real live fossil", since many tracks had previously been discovered in the Connecticut Valley (which she had often taken her students to see), but few actual dinosaur skeletons, and none at Mount Holyoke. She asked the owner of the land permission to collect the specimen for Mount Holyoke College (an all-women's college), where she was in charge of the department of geology, which was granted.[1][2][3]

The next day she brought a group of workmen to collect the specimen, and found another piece of sandstone that contained the rest of the fossil as well as impressions of those in the first slab. The specimen appeared to have been exposed for years with no one noticing it, the boulder having been broken open by people or frost. The fossil was brought to the laboratory where it was prepared and photographed.[1] The specimen consisted of dorsal (back) and caudal (tail) vetrebrae, a partial humerus (upper arm bone), ribs, the pubis, the ischium, the femora (thigh bones), the left tibia and fibula (lower leg bones), metatarsals, pedal phalanges (toe bones), and possible skull bones.[4] The light and delicate bones were in their natural position or nearly so within the rock, except for the tail and possible skull fragments, which were a few centimeters away from the skeleton.[1] The skull bones were identified as such because two of them were bilaterally symmetric, and one was broadly convex with a sulcus at the midline.[5]

The significance of the fossil was confirmed at an intercollegiate meeting of geology departments, and when the American paleontologist Richard Swann Lull subsequently encouraged Talbot to describe the specimen, she replied she did not know anything about dinosaurs, but Lull suggested she should study them and then describe it. In December 1910, Talbot read a preliminary description of the fossil at the Paleontological Society meeting at Pittsburgh, and in June 1911 she published a short scientific description, wherein she made the specimen the holotype of the new genus and species Podokesaurus holyokensis.[1][5] The generic name is derived from the Greek words podōkēs (ποδώκης) which means "swift (or fleet)-footed", an epithet commonly used in reference to the Greek hero Achilles, and saura (σαύρα) meaning "lizard", while the specific name refers to Holyoke. In full, the name can be translated as "swift-footed lizard of Holyoke".[5][2]

The discovery and naming of Podokesaurus made Talbot the first woman to find and describe a non-bird dinosaur.[6] The American paleontologist Robert T. Bakker stated in 2014 that while old professors grumbled that females were unfit for working with fossils, Talbot's discovery of Podokesaurus was a counterargument to that.[7] By the time the description was published, the fossil was sent to the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University for further preparation and study, where casts were also made of the bones as they lay in the rock. There, Lull created a model of the animal in life with missing parts based on Compsognathus, which Talbot described as having a "sardonic smile". Lull expanded on Mignon's article in his 1915 monograph Triassic life of the Connecticut valley, which contained a skeletal reconstruction and photograph of his model.[8][2][9] The Danish ornithologist Gerhard Heilmann published previously unpublished photos of the fossil received from Talbot in a 1913 Danish article wherein he compared the skeletons of dinosaurs and birds.[10][11]

Talbot wanted the fossil to stay at Yale or Washington on permanent exhibition, where it could "be with its kind", but it was kept at Mount Holyoke in the old science building Williston Hall as a local specimen, where it became a "pet curiosity" for the students. During the Christmas break of 1917, Williston Hall burned down, and no remains of the Podokesaurus fossil were found in the rubble. The American writer Christopher Benfey pointed out in 2002 that Podokesaurus therefore had the peculiar distinction of being the dinosaur that vanished twice in history.[2][1] While the college's fossil collections were almost entirely destroyed by the fire, facilities and collections continued to grow and improve due to Talbot's efforts.[12] No other Podokesaurus specimens have since been found, but casts of the type specimen remain at the Peabody Museum of Natural History and the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Podokesaurus received little further attention until abundant material of the small theropod Coelophysis was discovered in the late 1940s, and the anatomy of small theropods became clearer.[13][14]

Description

The type specimen suggests that Podokesaurus was a small, bipedal carnivore was about 90 cm (3 ft) long and 0.3 m (1 ft) tall. Its upper leg bone (femur) measures 86 mm in length, and its lower leg bone (tibia) measures 104 mm in length.[15]

A diagnosis is a statement of the anatomical features of an organism (or group) that collectively distinguish it from all other organisms. Some, but not all, of the features in a diagnosis are also autapomorphies. An autapomorphy is a distinctive anatomical feature that is unique to a given organism or group.

According to Colbert and Baird (1958), Podokesaurus can be distinguished from Coelophysis, and other dinosaurs based on the fact that neural spines on its dorsal vertebrae are anteroposteriorly shorter than those in Coelophysis bauri. Colbert and Baird (1958) also noted that a hip bone, the ischium, is "differently shaped" in Podokesaurus, when compared to Coelophysis, but did not describe how it was different.[15]

Classification

In 1914, the German paleontologist Friedrich von Huene named the new family Podokesauridae, in which he also included Saltopus, Procompsognathus, Coelophysis, and Tanystrophaeus.[16]

In 1958, the American paleontologists Edwin Harris Colbert and Donald Baird described a specimen consisting of natural bone casts of a theropod they found similar to Coelophysis and Podokesaurus from the same formation as the latter. While smaller than the others, these researchers suggested that because Podokesaurus was so similar to them, and that this raised questions as to its validity.[15] In 1964, Colbert formally synomymized Podokesaurus with Coelophysis, (since the latter name was older), coining the new combination C. holyokensis.[14] The American paleontologist Kevin Padian stated in 1986 that while Colbert's suggestion of synonymy was possible, the discernible similarities between Podokesaurus and Coelophysis were primitive theropod features, and the two were not as close in time as once thought.[17]

The name Podokesaurus is still commonly used to refer to the material, while being assigned to a more general Coelophysoidea, as the identity is hard to prove and Coelophysis dates from a different period. Tykoski and Rowe noted that Podokesaurus likely possesses coelophysoid characters, but does not preserve any derived traits that would unite it with Coelophysis, thus Podokesaurus is a valid genus separate from Coelophysis. With respect to its taxonomic group, Podokesaurus has been assigned to Coelophysoidea incertae sedis by Tykoski and Rowe.[18][19]

Podokesaurus shares the Coelophysidae taxon with Camposaurus and Coelophysis. It may also be related to Liliensternus, Procompsognathus, ?Pterospondylus, ?Segisaurus and ?Gojirasaurus.

Paleobiology

The skull is virtually unknown in Podokesaurus but based on the available material which suggests placement in the family Coelophysidae, it can be assumed that it was a small carnivorous theropod, that likely preyed on animals smaller than itself. Based on its skeletal morphology it can be ascertained that Podokesaurus was bipedal and, contrary to early illustrations, ran with its tail extended and off the ground. It has been estimated that Podokesaurus could run at 14 – 19 km/h (9 - 12 mph).[20]

Paleoenvironment

_(14743137946).jpg)

The hillock consists of material deposited by ice and having its probable origin in the Portland Formation in Massachusetts.

Podokesaurus was originally thought to have lived during the Late Triassic Period, which was later disproved. Podokesaurus was discovered in sediments deposited during the Pliensbachian–Toarcian stages of the Early Jurassic Period, between 190 and 174 million years ago.

See also

References

- Warner, F. L. (1937). "XII. Lost Dinosaur". On a New England Campus. Cambridge: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 279. ASIN B00085TO0O.

- Benfey, C. (2002). "Foreword: "A Route of Evanescence"". Changing Prospects: The View from Mount Holyoke. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8014-4119-6.

- "Mignon Talbot (1869-1950)". Daring to Dig. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Norman, D. B. (1990). "Problematic Theropoda". In Weishampel, D. B.; Osmolska, H.; Dodson, P. (eds.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 208, 301. ISBN 978-0-520-06727-1.

- Talbot, M. (1911). "Podokesaurus holyokensis, a new dinosaur from the Triassic of the Connecticut Valley". American Journal of Science. s4-31 (186): 469–479. Bibcode:1911AmJS...31..469T. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-31.186.469.

- Turner, S., Burek, C. & Moody, R.T., 2010, "Forgotten women in an extinct Saurian 'mans' World", In: Moody, R.T., Buffetaut, E., Martill, D. & Naish, D. Eds. Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. The Geological Society, London, Special Publication, 343: 111-153

- Baker, R. T. (2014). "A Tale of Two Compys: What Jurassic Park got right — and wrong — about dino anatomy". blog.hmns.org. The Houston Museum of Natural Science. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- Lull, R. S. (1915). "Triassic life of the Connecticut valley". (State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut. 24: 155–169. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.70405. ISBN 978-1167291937.

- Moodie, R. L. (1913). "Some Recent Advances in Vertebrate Paleontology. II". The American Naturalist. 47 (556): 248–256. doi:10.1086/279347. ISSN 0003-0147. JSTOR 2455799.

- Heilmann, G. (1913–1914). "Vor nuværende viden om fuglenes afstamning. Andet afsnit: Fugleligheder blandt fortidsøgler". Dansk Ornithologisk Forenings Tidsskrift (in Danish). 8: 56–65.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Wegemann, C. H.; Lyon, M. W. (1916). "Proceedings of the Academy and Affiliated Societies". Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences. 6 (9): 251–259. ISSN 0043-0439. JSTOR 24521263.

- Elder, E. S. (1982). "Women in Early Geology". Journal of Geological Education. 30 (5): 287–293. Bibcode:1982JGeoE..30..287E. doi:10.5408/0022-1368-30.5.287.

- Weishampel, D.B., (2006) Another look at the dinosaurs of the East Coast of North America. III Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontología de Dinosaurios y su Entorno, Salas de los Infantes, Burgos, Spain. Colectivo Arqueológico-Paleontológico Salense Actas, pp 129-168.

- Colbert, E. H. (1964). "The Triassic dinosaur genera Podokesaurus and Coelophysis". American Museum Novitates (2168). hdl:2246/3350.

- Colbert E.H. and Baird, D., 1958, "Coelurosaur bone casts from the Connecticut Valley Triassic", Am. Mus. Novitates 1901: 1-11

- von Huene, F. (1914). "Das natürliche System der Saurischia". Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie (in German). 5: 154–158.

- Padian, Kevin, 1986, On the type material of Coelophysis Cope (Saurischia: Theropoda) and a new specimen from the Petrified Forest of Arizona (Late Triassic: Chinle Formation), in Padian, K. ed., The beginning of the age of dinosaurs: Faunal change across the Triassic-Jurassic boundary: Cambridge, U.K., Cambridge University Press, p. 57-60.

- Tykoski, R.S. & Rowe, T. (2004). "Ceratosauria". In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.) The Dinosauria (2nd edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 64–70

- Olsen, P. E. 1980a . A comparison of the vertebrate assemblages from the Newark and Hartford Basins (early Mesozoic, Newark Supergroup) of eastern North America. In: Jacobs, L. L. (ed.). Aspects of Vertebrate History. Mus. No. Arizona Press, Flagstaff. Pp. 35–54.

- Thulborn, R. A. (1982). "Speeds and gaits of dinosaurs". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 38 (3–4): 227–256. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(82)90005-0.

External links

- Coelophysis - relation to Late Triassic Coelophysis, from the Illinois State Geographical Survey

- Coelophysis - relation to Late Triassic Coelophysis, from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles