Old Idaho State Penitentiary

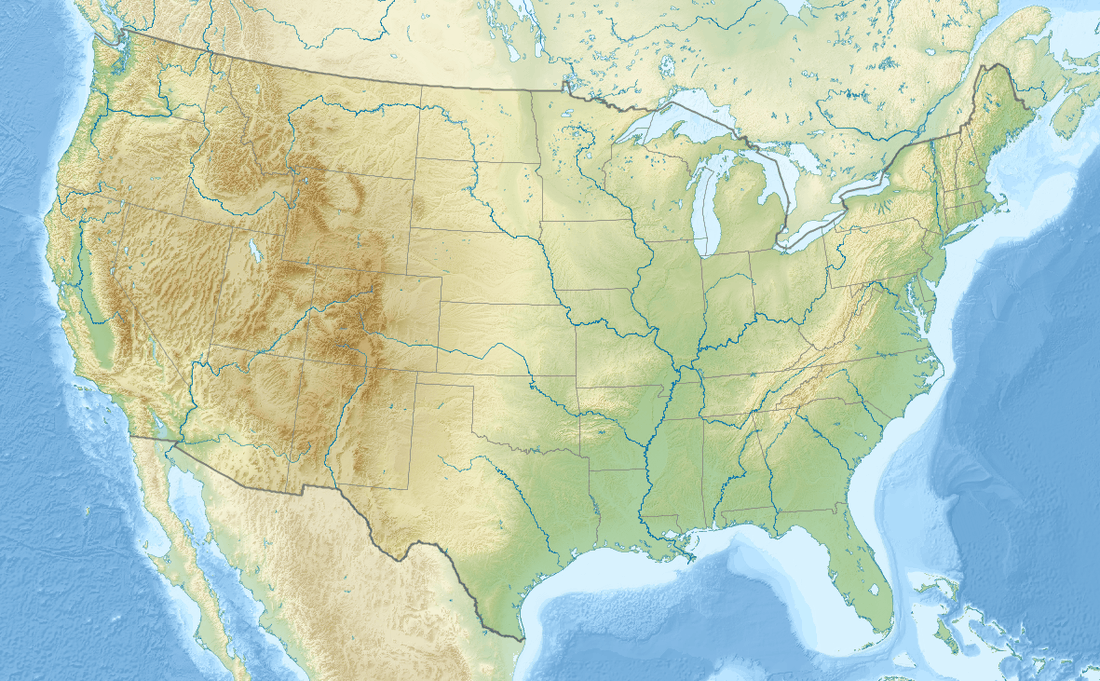

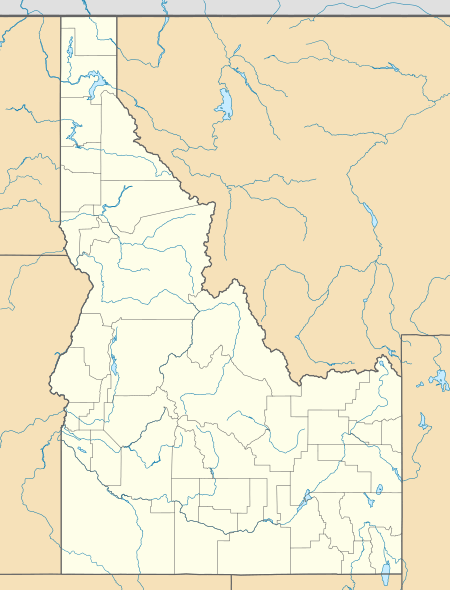

The Old Idaho Penitentiary State Historic Site was a functional prison from 1872 to 1973 in the western United States, east of Boise, Idaho. The first building, also known as the Territorial Prison, was constructed in the Territory of Idaho in 1870; the territory was seven years old when the prison was built, a full two decades before statehood.

Old Idaho Penitentiary State Historic Site | |

A facade of the Old Idaho State Penitentiary. | |

| Location | 2200 Warm Springs Ave. Boise, Idaho, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 43.6027°N 116.162°W |

| Area | 510 acres (2.1 km2) |

| Built | 1870–1872 |

| Architect | Inmates |

| Architectural style | Romanesque |

| NRHP reference No. | 74000729[1][2] |

| Added to NRHP | July 17, 1974 |

From its beginnings as a single cell house, the penitentiary grew to a complex of several distinctive buildings surrounded by a 17-foot-high (5.2 m) sandstone wall. The stone was quarried from the nearby ridges by the resident convicts, who also assisted in later constructions.[3]

The Old Idaho Penitentiary is operated by the Idaho State Historical Society;[4] the elevation of the site is approximately 2,770 feet (845 m) above sea level.

Prison history

Over its 101 years of operation, the penitentiary received more than 13,000 inmates, with a maximum population of a little over 600. Two hundred and fifteen of the inmates were women. Two famous inmates were Harry Orchard and Lyda Southard. Orchard assassinated former Governor Frank Steunenberg in 1905 and Southard was known as Idaho's Lady Bluebeard for killing several of her husbands to collect upon their life insurance.[4]

Serious riots occurred in 1952 (May 24),[5][6][7] 1971 (August 10),[8][9][10] and 1973 (March 7–8)[11][12] over living conditions in the prison. The 416 resident inmates were moved to the new Idaho State Correctional Institution south of Boise and the Old Idaho Penitentiary was closed on December 3, 1973.[13][14]

In 1992, the Idaho State Historical Society recorded oral history interviews with fifteen former prison guards. These tapes and transcripts cover prison operations and remembrances from the 1950s to the closing of the prison. The collection is open for research at the society.[15]

Prison Buildings

The Territorial Prison was completed in 1872 and received its first 11 inmates from the Boise County Jail. This building was converted into a Chapel in the 1930s and was destroyed by fire in the 1973 riot.[12]

The New Cell House (1889–1890) consisted of three tiers of 42 steel cells. The third tier closest to the Rose Garden served as "Death Row."

The area now known as the Rose Garden (as this is what it is now) was once used to execute prisoners by hanging. Of the 10 executions in the Old State Penitentiary, six occurred here.

The Administration Building (1893–1894) housed the warden's office, armory, visitation room, control room and the turn key area.

The False Front Buildings (1894–1895) held the commissary, trusty dorm, barber shop (1902–1960s) and hospital (originally the blacksmith shop, but was remodeled in 1912 and remained the prison hospital until the 1960s).

The Dining Hall (1898) was designed by George Hamilton (an inmate at the time) and burned down in the 1973 riot.

Cell House 2 (1899), also known as the "North Wing," contained two-man cells. A honey bucket was placed in each cell to serve as a toilet. Inmates burned the building in the 1973 riot.[12]

Cell House 3 (1899) was built the same as Cell House 2. It was eventually condemned for habitation, but in 1921 was converted into a shoe factory. In 1928, this building was remodeled for inmate occupancy and became the first cell house with indoor plumbing.

The Women's Ward (1905–1906) was built out of necessity. Prior to its completion women did not have separate quarters. Male inmates built a wall around the old wardens home to serve as a separate facility for women. This building had seven two-person cells, a central day room, kitchen and bathroom facilities. This building held the infamous Lyda Southard.

Built by inmates, the Multipurpose Building (1923) served as a shirt factory, shoe shop, bakery, license plate shop, laundry, hobby room, and loafing room and housed the communal showers.

Solitary confinement consisted of two sections. The first, built in the early 1920s, was the Cooler. Although built for solitary confinement, each cell contained 4–6 men. The second section, known as Siberia, was built in 1926 and housed twelve 3-by-8-foot (0.9 m × 2.4 m) cells, with one inmate per cell.

Cell House 4 (1952) was the largest and most modern cell house at the penitentiary. Some inmates painted their cells and left drawings on the walls that can be seen today.

Cell House 5 (1954) was Maximum Security where the most unruly and violent offenders stayed. This building also served as a permanent place of solitary confinement. It includes a built-in gallows and "Death Row."

Although not a building, there is also an outdoor Recreational Area where inmates boxed and played baseball, basketball, handball, tennis, horseshoes and football. The baseball, and later softball, team was named "The Outlaws" and frequently played teams from across the Treasure Valley.[16]

Museum and Historical Society

The site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973 for its significance as a Territorial Prison. The site currently contains museums, an arboretum and is a facility managed by the Idaho State Historical Society.[17]

In late 1999, J.C. Earl donated his personal collection of historic arms and military memorabilia to the state of Idaho. These items were placed on exhibition as the J.C. Earl Exhibit at the Old Idaho Penitentiary. They range from the Bronze Age to those used today for sport, law enforcement, and military purposes. The Luristan Bronze collection dates to about 1000-650 BC.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "State Listings: Idaho, Ada County". National Register of Historic Places. American Dreams Inc. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- Wollheim, Peter (2005). "Correction by design". Idaho Issues Online. Center for Idaho History and Politics. ISSN 1553-9148. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- "Visit the Old Idaho Penitentiary". Idaho State Historical Society. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- "Tear gas ends riot by 300 in Idaho prison". Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. May 25, 1952. p. 3.

- Lewis, Phil; Leeright, Bob (May 25, 1952). "Tear gas routs 300 Idaho cons after 4 hour riot". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. p. 1.

- "Governor backs prison warden". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. May 26, 1952. p. 1.

- "Buildings burned at Idaho prison". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. August 11, 1971. p. 1.

- "Idaho prison quiet again". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). Associated Press. August 11, 1971. p. 1.

- Jester, Earle A. (August 12, 1971). "Idaho governor denies amnesty in prison riot". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. p. 1.

- "Inmates defiant". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). AP photo. March 8, 1973. p. 3.

- "Officials probing inmate-set fires". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington. March 9, 1973.

- "Inmates move to new prison". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. December 4, 1973. p. 3.

- Marsh, Robert L.; Patrick, Steven T. (2005). "Hard Choices". Idaho Issues Online. Center for Idaho History and Politics. ISSN 1553-9148. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- Hodges, Kathy (1992–1999). Guide to the Idaho Old Penitentiary Former Guards Oral History Project: 1950s-1970s. Idaho State Historical Society. Idaho State Archives (Formerly known as the Public Archives and Research Center). Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- Idaho State Historical Society. Old Idaho Penitentiary State Historic Site [Brochure]. Boise, ID: ISHS.

- "Old Idaho Penitentiary timeline" (PDF). Education Programs. Idaho State Historical Society. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old Idaho State Penitentiary. |

- Old Idaho Penitentiary Idaho State Historical Society

- Inmates Catalog (1864-1975) Idaho State Historical Society

- A Place of Confinement: Constructing the Old Idaho State Penitentiary 1872-1973 Idaho State Historical Society

- Idaho Architecture Project – Idaho Penitentiary

- Old Boise Penitentiary (Photo Essay) Idaho for 91 Days

- Old Idaho Penitentiary on LocalWiki