Nicolo Schiro

Nicolo "Cola" Schiro (born Nicolò Schirò;[lower-alpha 1] Italian pronunciation: [nikoˈlɔ skiˈrɔ]; September 2, 1872 – April 29, 1957) was an early Sicilian-born New York City mobster who, in 1912, became the boss of the mafia gang which later became known as the Bonanno crime family. In 1930, a conflict with rival mafia boss Joe Masseria would force Schiro out and elevate Salvatore Maranzano as his replacement. Following his ouster, Schiro returned to Sicily.

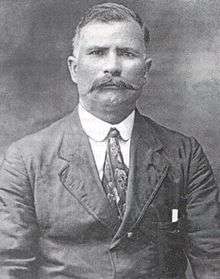

Nicolo Schiro | |

|---|---|

Schiro, 1923 | |

| Born | Nicolò Schirò September 2, 1872 |

| Died | April 29, 1957 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | Italian, American (renounced citizenship) |

| Other names | "Cola", Nicola Schiro |

| Occupation | Crime boss, mobster |

| Allegiance | Schiro crime family |

Early life

Nicolò Schirò was born on September 2, 1872 in the town of Roccamena, in the Province of Palermo, Sicily to Matteo Schirò and his wife, Maria Antonia Rizzuto. He was named after his paternal grandfather, a mayor of Roccamena in the 1840s who came from the Arbëreshë community of Contessa Entellina.[2]

A few years later, Schiro's family moved to his mother's hometown in nearby Camporeale.[2] Paolo Orlando, a cousin born in Camporeale, reportedly became a mafia boss in the large Italian community of the French colony of Tunis.[3][4] Schiro immigrated to the United States in 1897,[2] and by 1902 had settled in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn.[5]

Mafia boss

In 1912, Schiro replaced Sebastiano DiGaetano, an immigrant from the Sicilian town of Castellammare del Golfo, as the head of the local mafia centered in Williamsburg.[3] Salvatore Clemente, a Secret Service informer in the Morello gang, claimed that DiGaetano was stepping down because he had "lost his nerve." Shortly after Schiro became boss, DiGaetano disappeared.[2] A factor in Schiro's elevation may have been the presence in Brooklyn of his cousin, Paolo Orlando, who reportedly had been forced to leave Tunis.[4] Orlando remained in Brooklyn until the end of World War I.[6]

At this time another mafia boss in New York City, Salvatore D'Aquila, was bestowed the title Capo dei capi by other mafiosi. Clemente told his Secret Service handlers in November 1913 that Schiro was aligned with the Morello gang in a war against D'Aquila.[7] A truce seems to have been called between the factions by the end of the year which held until the May 23, 1914, murder of Fortunato LoMonte under D'Aquila's orders. LoMonte had taken over the Morello gang after Giuseppe Morello's 1910 conviction for counterfeiting. After the killing started again, Schiro maintained a neutral position, siding with neither the D'Aquila gang nor the Morello gang.[8]

Schiro ran his gang conservatively, conducting its criminal activity primarily among Sicilian immigrants while avoiding attention from authorities and co-operating with other non-Sicilian gangs.[9] He also developed close relationships with local business and political leaders,[10] including being on the board of directors of the local United Italian-American Democratic Club.[11]

Schiro became a naturalized United States citizen in 1914.[12]

On November 11, 1917, two Schiro gang members, Antonio Mazzara and Antonino DiBenedetto were shot to death near the intersection of North 5th and Roebling streets in Brooklyn. One of the two gunmen, Antonio Massino, was arrested near the scene but the other, Detroit mobster Giuseppe Buccellato escaped. Buccellato killed Mazzara and DiBenedetto after they refused to divulge the whereabouts of fellow Schiro gangster, Stefano Magaddino, believing Magaddino was behind the murder earlier that March of his brother and fellow Detroit gangster, Felice Buccellato, due to a feud between the mafia clans of Magaddino and Buccellato back in their hometown of Castellammare del Golfo.[13][14] Failing to locate and kill Buccellato, the Schiro gang shot and killed his associate, Francesco Finazzo, at Finazzo's home located on the same corner where Mazzara and DiBenedetto had been murdered a month earlier.[15]

"The Good Killers"

On August 16, 1921, Vito Bonventre, Stefano Magaddino, Magaddino's brother-in-law Bartolo DiGregorio, Francesco Puma, and two other gangsters were arrested for the murder of Camillo Caiozzo a couple of weeks earlier.[16] This followed the confession of Bartolo Fontana, the gunman who had shot and killed Caiozzo. Fontana identified the men as members of the "Good Killers," a group of mafioso from Castellammare del Golfo who were leading members of the Schiro gang. Fontana said they ordered him to kill Caiozzo in retaliation for Caiozzo's involvement in the 1916 murder of Magaddino's brother, Pietro Magaddino, back in Sicily. Fontana also revealed that the "Good Killers" were responsible for a string of other murders.[16] Some of the victims he named were connected to the Buccellato family, who's mafia clan in Castellammere del Golfo opposed one run there by the families of Bonventre and Magaddino.[17]

Some of the victims named by Fontana were former supporters of Salvatore Loiacano, who had been backed by Salvatore D'Aquila to take over the Morello crime family. Loiacano was murdered on December 10, 1920, not long after Giuseppe Morello was released from prison. According to a March 1, 1921 article in the New York Evening World, seven men had placed their hands on Loiacano's corpse during his funeral and vowed revenge. Within a few months, three of the vow makers - Salvatore Mauro, Angelo Patricola, and Giuseppe Granatelli had been murdered and a fourth, Angelo Lagattuta was shot and severely wounded. They were all named by Fontana as victims of the "Good Killers," with Fontana unaware that Lagattuta had survived. Morello had made a deal with Schiro, his earlier ally against D'Aquila, to kill Loiacano's supporters with people unfamiliar to them.[18][19]

The government's case against the "Good Killers" for Caiozzo's murder collapsed with only Fontana's testimony against them. Puma was murdered while out on bail awaiting his trial.[20] Fontana went to prison for the murder with the charges against Magaddino and the four others being dropped over time.[16] Magaddino fled New York City after his release, ending up in the Buffalo, New York area.[21]

1920s and Prohibition

Schiro avoided the media and was never arrested for a crime during his time as boss.[9] Several former members of the Schiro crime family would become the bosses of gangs in other cities – Frank Lanza in San Francisco, Stefano Magaddino in Buffalo, and Gaspare Messina in New England.[22]

Giovanni Battista Dibella, a member of Schiro's gang, was arrested (under the alias Piazza) on July 14, 1921, when over $100,000[lower-alpha 2] worth of whiskey and numerous forged medicinal liquor permits were seized during a raid by Prohibition agents Izzy Einstein and Moe Smith at Dibella's olive oil warehouse at 177 Boerum Avenue in Brooklyn.[24][25] Schiro had been a witness at Dibella's wedding in 1912.[26] On September 12, 1922, Dibella's brother, Salvatore, was arrested and later convicted (also under the alias Piazza) for killing 17 year-old Gutman Diamond, a messenger for Western Union, while shooting at another bootlegger.[27][28]

Salvatore Maranzano, a son-in-law of a mafia boss in Trapani, left Italy in 1925. Born in Castellammare del Golfo, he joined the Schiro gang with its numerous members from there; soon helping it create an extensive bootlegging network in Dutchess County, New York, along with a ring providing fraudulent documents to Italians smuggled into the United States.[29][30]

Joseph Bonanno illegally immigrated to the U.S. during the 1920s,[31] soon becoming a protege of Maranzano and joining the Schiro gang.[32] In his autobiography, Bonanno describes Schiro as "a compliant fellow with little backbone" and "being extremely reluctant to ruffle anyone".[33] Bonanno's second cousin, Vito Bonventre remained a leader within Schiro's gang following his arrest and release during the "Good Killers" affair. During Prohibition, Bonventre developed a widespread bootlegging operation with Bonanno recalling "Next to Schiro, Bonventre was probably the most wealthy" of the gang.[34]

Conflict with Masseria

Salvatore D'Aquila was killed on October 10, 1928.[35] Joe Masseria, the leader of a gang that emerged from the old Morello crime family, was selected to replace D'Aquila as the new Capo dei capi that winter.[36] After his elevation, Masseria began applying pressure to other mafia gangs for monetary tributes.[37] Other mobsters accused him of orchestrating the 1930 murders of Gaspar Milazzo in Detroit and Gaetano Reina in the Bronx. Schiro tried to replicate the strategy of neutrality he used to deal with D'Aquila with Masseria but he was vigorously opposed by Salvatore Maranzano and Buffalo boss Stefano Magaddino.[38] Masseria claimed Schiro had committed a transgression and demanded Schiro pay him $10,000[lower-alpha 3] and step down as leader of his mafia crime family. Schiro complied. Soon after, Vito Bonventre was murdered at his home on July 15, 1930.[39] This led to Maranzano being elevated to boss of the gang and a conflict with Masseria and his allies referred to as the Castellammarese War.[40]

Return to Sicily

Following Schiro's ouster as boss in 1930, he returned to Italy; settling in his old hometown of Camporeale in Sicily. In 1934, a memorial was dedicated in Camporeale to its soldiers killed during World War I. It was built from donations of Camporealese immigrants in America collected by Schiro.[41][42]

Schiro renounced his U.S. citizenship at the American consulate in Palermo on October 14, 1949.[43] He died in Camporeale on April 29, 1957.[44]

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- Dash 2010, p. 320.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, p. 55.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, pp. 54–55.

- Petacco 1974, pp. 168–169.

- Critchley 2009, p. 214.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, p. 52.

- Dash 2010, p. 324.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, pp. 59–61.

- Critchley 2009, p. 137.

- Waugh 2019, p. 400 n198.

- "Italian-American Democrats' Election". The Brooklyn Standard Union. 14 December 1916. p. 8.

- Critchley 2009, p. 311 n127.

- Waugh 2019, pp. 194-195.

- "TWO DIE IN STREET AFTER SEVEN SHOTS; Detective Pursues Two Men With Pistols and Makes One a Prisoner". New York Herald. 12 November 1917.

- Waugh 2019, p. 196.

- Hunt, Thomas; Tona, Michael A. (Spring 2007). "The Good Killers 1921's Glimpse of the Mafia". On the Spot Journal of Crime and Law Enforcement History. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2019 – via The American Mafia.

- Critchley 2009, pp. 216–229.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, p. 64.

- "5th MAN DONE FOR OUT OF EIGHT IN DEADLY VENDETTA; First Victim Picked Off on Dec. 10 Last - Seven Swore to Avenge Him.; SECOND 'GOT' ON DEC. 29; Next on Jan. 23, and So On - Now the Three Await, Still Vengeful". The Evening World. 1 March 1921. p. 1.

- "CONVICT KILLED, GIRL SHOT, FROM ASSASSIN AUTO". New York Daily News. 5 November 1922.

- Critchley 2009, pp. 216–222.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, pp. 55–56.

- "CPI Inflation Calculator". www.bls.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-19.

- Schmitt 2012, pp. 58–59.

- "FEDERAL DRY SQUAD MAKES BIG HAUL; Whiskey Valued at $100,000 and Fake Permits Seized in Boerum Street Raild; 500 BARRELS IN TRANSIT; Proprietor of Oil Concern Faces Conspiracy Charge". The Brooklyn Standard Union. 15 July 1921. p. 3.

- Schmitt 2012, p. 59.

- Schmitt 2012, pp. 59–60.

- "Piazza Gets Term of 3 Years in Jail". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 2 April 1923. Retrieved 17 February 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Critchley 2009, pp. 144–147.

- Lupo 2015, p. 57.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, pp. 55–61.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, pp. 70–71, 76–80.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, p. 93.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, pp. 78, 102–103.

- Critchley 2009, p. 157.

- Hortis 2014, p. 74.

- Hortis 2014, pp. 80–81.

- Bonanno & Lalli 1983, p. 96.

- "Wealthy Baker Slain; Police Hint at Mafia: 2 Men Seen Running From Place". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 15 July 1930. Retrieved 3 March 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Critchley 2009, pp. 165–191.

- Accardo, Luigi (1995). Camporeale: Origini, Usi, Costumi, Mentalita, Proverbi, Canti popolari (in Italian). Alcamo, Sicily: Edizioni Campo. pp. 54–55.

- "Museo/Monumento" (in Italian). Comune di Camporeale.

- Critchley 2009, p. 311n127.

- Warner, Santino & Van't Reit 2014, p. 53.

Sources

- Bonanno, Joseph; Lalli, Sergio (1983). A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno. New York: Simon & Schuster.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buccellato, James A. (2015). Early Organized Crime in Detroit: Vice, Corruption and the Rise of the Mafia. Charleston: The History Press. ISBN 9781625855497.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Critchley, David (2009). The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415990301.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dash, Mike (2010). The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder and the Birth of the American Mafia. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345523570.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hortis, C. Alexander (2014). The Mob and the City: The Hidden History of how the Mafia Captured New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 9781616149239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lupo, Salvatore (2015). The Two Mafias: A Transatlantic History, 1888-2008. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9781137491374.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petacco, Arrigo (1974). Joe Petrosino. Trans. by Charles Lam Markmann. New York: MacMillan Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmitt, Gavin (July 2012). "The Underworld's Interest in Wisconsin's Cheese". Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement: 56–65.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warner, Richard; Santino, Angelo; Van't Reit, Lennert (May 2014). "Early New York Mafia: An Alternative Theory". Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waugh, Daniel (2019). Vinnitta: The Birth of the Detroit Mafia. Lulu Publishing Services. ISBN 9781483496276.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Struggle for Control - The Gangs of New York, article by Jon Black at GangRule.com.

- Detroit fish market murders spark Mafia war, article by Thomas Hunt at The Writers of Wrongs.

- Two killed at Castellammarese colony in Brooklyn, article by Thomas Hunt at The Writers of Wrongs.

- Nicolo Schiro information in the FBI file of James Lanza, from the Internet Archive.

| American Mafia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sebastiano DiGaetano |

Bonanno crime family Boss 1912–1930 |

Succeeded by Salvatore Maranzano |