Nicodemus

Nicodemus (/ˌnɪkəˈdiːməs/; Greek: Νικόδημος, translit. Nikódēmos) was a Pharisee and a member of the Sanhedrin mentioned in three places in the Gospel of John:

- He first visits Jesus one night to discuss Jesus' teachings (John 3:1–21).

- The second time Nicodemus is mentioned, he reminds his colleagues in the Sanhedrin that the law requires that a person be heard before being judged (John 7:50–51).

- Finally, Nicodemus appears after the Crucifixion of Jesus to provide the customary embalming spices, and assists Joseph of Arimathea in preparing the body of Jesus for burial (John 19:39–42).

Saint Nicodemus | |

|---|---|

Nicodemus helping to take down Jesus' body from the cross (Pietà, by Michelangelo) | |

| Defender of Christ | |

| Born | Judea |

| Died | Judea |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Roman Catholic Church Oriental Orthodox Church Anglican Church Lutheran Church |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Feast | August 2 (Eastern Orthodox Church & Byzantine Catholic Churches) August 3 (Roman Catholic Church) Third Sunday of Pascha (Eastern Orthodox Church & Byzantine Catholic Churches) August 31 (Roman Catholic Church) |

| Attributes | Pharisee |

| Patronage | Curiosity |

An apocryphal work under his name—the Gospel of Nicodemus—was produced in the mid-4th century, and is mostly a reworking of the earlier Acts of Pilate, which recounts the Harrowing of Hell.

Although there is no clear source of information about Nicodemus outside the Gospel of John, Ochser and Kohler (in an article in the Jewish Encyclopedia) and some historians[1] have speculated that he could be identical to Nicodemus ben Gurion, mentioned in the Talmud as a wealthy and popular holy man reputed to have had miraculous powers. Others point out that the biblical Nicodemus is likely an older man at the time of his conversation with Jesus, while Nicodemus ben Gurion was on the scene 40 years later, at the time of the Jewish War.[2]

In John's Gospel

.jpg)

As is the case with Lazarus, Nicodemus does not belong to the tradition of the Synoptic Gospels and is only mentioned by John,[3] who devotes more than half of Chapter 3 of his gospel, a few verses of Chapter 7 and lastly mentions him in Chapter 19.

The first time Nicodemus is mentioned, he is identified as a Pharisee who comes to see Jesus "at night". John places this meeting shortly after the Cleansing of the Temple and links it to the signs which Jesus performed in Jerusalem during the Passover feast. "Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God. For no one could perform the signs you are doing if God were not with him" (John 3:2).

Then follows a conversation with Nicodemus about the meaning of being "born again" or "born from above" (Greek: ἄνωθεν), and mention of seeing the "kingdom of God". Nicodemus explores the notion of being literally born again from one's mother's womb, but most theologians recognise that Nicodemus knew Jesus was not speaking of literal rebirth. Theologian Charles Ellicott wrote that "after the method of Rabbinic dialogue, [Nicodemus] presses the impossible meaning of the words in order to exclude it, and to draw forth the true meaning. 'You cannot mean that a man is to enter the second time into his mother’s womb, and be born. What is it, then, that you do mean?'"[4] Other scholars recognize that ἄνωθεν, anōthen is a double entendre that is a narrative device to lead a character (and the implied reader) to a newer understanding of deep import.[5] In this instance, Nicodemus chooses the literal (rather than the figurative) meaning of anōthen and assumes that that meaning exhausts the significance of the word.

Jesus expresses surprise, perhaps ironically, that "a teacher of Israel" does not understand the concept of spiritual rebirth. James F. Driscoll describes Nicodemus as a learned and intelligent believer, but somewhat timid and not easily initiated into the mysteries of the new faith.[3]

In Chapter 7, Nicodemus advises his colleagues among "the chief priests and the Pharisees", to hear and investigate before making a judgment concerning Jesus. Their mocking response argues that no prophet comes from Galilee. Nonetheless, it is probable that he wielded a certain influence in the Sanhedrin.[3]

Finally, when Jesus is buried, Nicodemus brought a mixture of myrrh and aloes—about 100 Roman pounds (33 kg)—despite embalming being generally against Jewish custom (with the exceptions of Jacob and Joseph).[John 19:39] Nicodemus must have been a man of means; in his book Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week, Pope Benedict XVI observes that, "The quantity of the balm is extraordinary and exceeds all normal proportions. This is a royal burial."[6]

Veneration and liturgical commemoration

Nicodemus is venerated as a saint in the various Eastern Churches and in the Roman Catholic Church. The Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic churches commemorate Nicodemus on the Sunday of the Myrrhbearers, celebrated on the Third Sunday of Pascha (i.e., the second Sunday after Easter) as well as August 2, the date when tradition holds that his relics were found, along with those of Stephen the Protomartyr, Gamaliel, and Abibas (Gamaliel's second son). The traditional Roman Catholic liturgical calendar lists the same feast of the finding of their relics on the following day, August 3.

In the current Roman Martyrology of the Catholic Church, Nicodemus is commemorated along with Saint Joseph of Arimathea on August 31. The Franciscan Order erected a church under the patronage of Saints Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea in Ramla.

Legacy

In art

.jpg)

Nicodemus figures prominently in medieval depictions of the Deposition in which he and Joseph of Arimathea are shown removing the dead Christ from the cross, often with the aid of a ladder.

Like Joseph, Nicodemus became the object of various pious legends during the Middle Ages, particularly in connection with monumental crosses. He was reputed to have carved both the Holy Face of Lucca and the Batlló Crucifix, receiving angelic assistance with the face in particular and thus rendering the works instances of acheiropoieta.[7]

Both of these sculptures date from at least a millennium after Nicodemus' life, but the ascriptions attest to the contemporary interest in Nicodemus as a character in medieval Europe.

In poetry

In Henry Vaughan's "The Night," mentioning Nicodemus is significant to elaborate the poem's depiction of the night's relationship with God.

In music

In the Lutheran prescribed readings of the 18th century, the gospel text of the meeting of Jesus and Nicodemus at night was assigned to Trinity Sunday. Johann Sebastian Bach composed several cantatas for the occasion, of which O heilges Geist- und Wasserbad, BWV 165, composed in 1715, stays close to the gospel based on a libretto by the court poet in Weimar, Salomo Franck.

Ernst Pepping composed in 1937 an Evangelienmotette (motet on gospel text) Jesus und Nikodemus.

In popular music, Nicodemus' name was figuratively used in Henry Clay Work's 1864 American Civil War-era piece "Wake Nicodemus",[8] which at that time was popular in minstrel shows. In 1978 Tim Curry covered the song on his debut album Read My Lips. The song "Help Yourself" by The Devil Makes Three contains a very informal retelling of the relationship between Nicodemus and Jesus.

Second verse of the song "Help yourself" performed by The Devil Makes Three (band) is dedicated to Nicodemus.

In literature

Persuaded: The Story of Nicodemus by author David Harder is a historical fictional account on the life of Nicodemus. Harder used events and timetables for his novel found within the pages of the Passion Translation version of the Bible and brought biblical characters to life in a realistic story with the goal of keeping his book historically and scripturally accurate.

During the Protestant vs. Catholic struggle

During the struggle between Protestants and Catholics in Europe, from the 16th century to the 18th, a person belonging to a Church different from the locally dominant one often risked severe punishment – in many cases a literal life danger. At that time, there developed the use of "Nicodemite", usually a term of disparagement referring to a person who is suspected of public misrepresentation of their actual religious beliefs by exhibiting false appearance and concealing true beliefs.[9][10] The term was apparently introduced by John Calvin in his 1544 Excuse à messieurs les Nicodemites.[11] To Calvin, who opposed all veneration of saints, the fact of Nicodemus becoming a Catholic saint in no way exonerated his "duplicity". The term was originally applied mainly to crypto-protestants – hidden Protestants in a Catholic environment – later used more broadly.

United States

The discussion with Jesus is the source of several common expressions of contemporary American Christianity, specifically, the descriptive phrase "born again" used to describe salvation or baptism by some groups, and John 3:16, a commonly quoted verse used to describe God's plan of salvation.

Daniel Burke notes that, "To blacks after the Civil War, he was a model of rebirth as they sought to cast off their old identity as slaves".[6] Rosamond Rodman asserts that freed slaves who moved to Nicodemus, Kansas, after the Civil War named their town after him.[6] However, the National Park Service indicates that it was more likely based on an 1864 song, "Wake Nicodemus" by Henry Clay Work, used to promote settlement in the area.[12]

On August 16, 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. invoked Nicodemus as a metaphor concerning the need for the United States to be "born again" in order to effectively address social and economic inequality. The speech was called "Where Do We Go From Here?," and delivered at the 11th Annual SCLC Convention in Atlanta, Georgia.[13]

Gallery

- Nicodemus in art

Jesus and Nicodemus by Crijn Hendricksz, 1616–1645

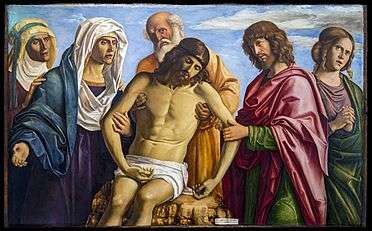

Jesus and Nicodemus by Crijn Hendricksz, 1616–1645 Cima da Conegliano, Nicodemus with Christ's body, Apostle John on the right and Mary to left.

Cima da Conegliano, Nicodemus with Christ's body, Apostle John on the right and Mary to left. Entombment, by Pietro Perugino, with Nicodemus and Joseph from Arimatea

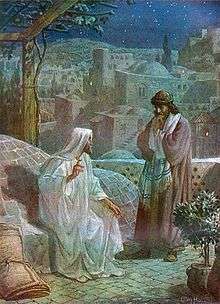

Entombment, by Pietro Perugino, with Nicodemus and Joseph from Arimatea Nicodemus (right) talking to Jesus, by William Brassey Hole, (1846–1917)

Nicodemus (right) talking to Jesus, by William Brassey Hole, (1846–1917) Tanner – Nicodemus coming to Christ II

Tanner – Nicodemus coming to Christ II

See also

- Saint Nicodemus, patron saint archive

Notes

- See, for instance, David Flusser, Jesus (Jerusalem: Magnes, 2001), 148; idem, "Gamaliel and Nicodemus", JerusalemPerspective.com; Zeev Safrai, "Nakdimon b. Guryon: A Galilean Aristocrat in Jerusalem" in The Beginnings of Christianity (ed. Jack Pastor and Menachem Mor; Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2005), 297–314.

- Carson, D. A. (1991). The Gospel according to John. Leicester: InterVarsity. p. 186; Richard Bauckham, "Nicodemus and the Gurion Family", Journal of Theological Studies 47.1 (1996):1–37.

- Driscoll, James F. "Nicodemus." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 13 Dec. 2014.

- Watkins, H. W., Ellicott's Commentary for English Readers on John 3, accessed 10 February 2016

- James L. Resseguie, "A Glossary of New Testament Narrative Criticism with Illustrations," in Religions, 10 (3) 217), 10-11.

- Burke, Daniel. Nicodemus, The Mystery Man of Holy Week, Religious News Service, March 27, 2013.

- Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Art. Volume 2. The Passion of Jesus Christ. Janet Seligman (tr.), Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1972: 144–45, 472–73.

- "Henry Clay Work Biography". notablebiographies.com.

- Overell 2004, pp. 117–18.

- Livingstone 2000

- Eire 1979.

- "Nicodemus National Historic Site", National Park Service.

- King Jr., Martin Luther (August 16, 1967). ""Where Do We Go From Here?," Address Delivered at the Eleventh Annual SCLC Convention". The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

References

- Cornel Heinsdorff: Christus, Nikodemus und die Samaritanerin bei Juvencus. Mit einem Anhang zur lateinischen Evangelienvorlage (= Untersuchungen zur antiken Literatur und Geschichte, Bd.67), Berlin/New York 2003

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nicodemus. |

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Nicodemus

- "St. Nicodemus", Butler's Lives of the Saints

Nicodemus | ||

| Preceded by Temple Cleansing |

New Testament Events |

Succeeded by Samaritan Woman at the Well |