Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire

The Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire was the last war fought by the Neo-Assyrian Empire between 626 and 609 BC. The multiple failed offensives against the Medes and the Neo-Babylonian Empire ultimately led to the destruction of the Assyrian Empire, which had dominated the ancient Near East since 911 BC.

| Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

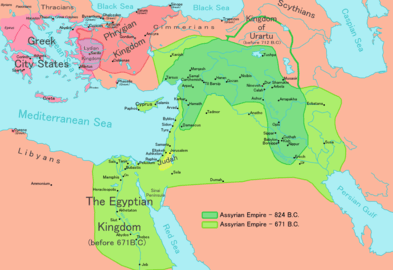

Map of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 824 BC (dark green) and in its apex in 671 BC (light green) under King Esarhaddon | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Medes Babylonians |

Assyrians Egypt | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Cyaxares Nabopolassar |

Sinsharishkun Ashur-uballit II Necho II | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Background

In the first half of the seventh century BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire was at the height of its power, the entire Fertile Crescent was under its control and the Assyrians had established an allied dynasty in Egypt. However, when Assurbanipal died of natural causes in 631 BC,[4] his son Ashur-etil-ilani became king. As often in Assyrian history, Ashur-etil-ilani's rise to the Assyrian throne was initially met with opposition and unrest[5] as an Assyrian official called Nabu-rihtu-usur attempted to usurp the Assyrian throne with the help of another official, Sin-shar-ibni, but the king, with the probable help of Sin-shumu-lishir, stopped Nabu-rihtu-usur and Sin-shar-ibni[4] and the conspiracy appears to have been crushed relatively quickly.[5] However, it is possible that some of Assyria's vassals used the reign of what they perceived to be a weak ruler to free themselves from Assyrian control and even attack Assyrian outposts. In c. 628 BC, Josiah, an Assyrian vassal and the king of Judah in the Levant, extended his land so that it reached the coast, capturing the city of Ashdod and settling some of his own people there.[6] Ashur-etil-ilani's end is unclear, but it is frequently assumed, without any supporting evidence, that Ashur-etil-ilani's brother Sinsharishkun fought with him for the throne[7] and, ultimately, ascended to the throne in the middle of 627 BC.[8] Roughly at the same time, the vassal king of Babylon, Kandalanu, died which led to Sinsharishkun also becoming the ruler of Babylon, as proven by inscriptions by him in southern cities such as Nippur, Uruk, Sippar and Babylon itself.[9]

Course of the war

Rise of Babylon

Sinsharishkun's rule of Babylon did not last long, as almost immediately in the wake of him coming to the throne, the general Sin-shumu-lishir rebelled.[8] Sin-shumu-lishir was a key figure during Ashur-etil-ilani's reign, putting down several revolts and possibly being the de facto leader of the country. The rise of another king might have endangered his position and as such led him to revolt and attempt to seize power for himself.[9] Sin-shumu-lishir seized some cities in northern Babylonia, including Nippur and Babylon itself and would rule there for three months before being defeated by Sinsharishkun.[8] Babylonia's governor, Nabopolassar, possibly using the political instability caused by the previous revolt[8] and the ongoing interregnum in the south,[10] assaulted both Nippur and Babylon.[n 1] and in the aftermath of a failed Assyrian counterattack, Nabopolassar was formally crowned King of Babylon on November 22/23 626 BC, restoring Babylonia as an independent kingdom.[11]

In 625–623 BC, Sinsharishkun's forces again attempted to defeat Nabopolassar, campaigning in northern Babylonia. Initially, these campaigns were successful; in 625 BC the Assyrians took the city of Sippar and Nabopolassar's attempt to reconquer Nippur failed. Another Assyrian vassal, Elam, also stopped paying tribute to Assyria during this time and several Babylonian cities, such as Der, revolted and joined Nabopolassar. Realizing the threat this posed, Sinsharishkun led a massive counterattack himself which saw the successful recapture of Uruk in 623 BC.[12] Sinsharishkun could possibly have ultimately been victorious but another revolt, led by an Assyrian general, occurred in the empire's western provinces in 622 BC.[12] This general, whose name remains unknown, took advantage of the absence of Sinsharishkun's forces to march on Nineveh, met an army which surrendered without fighting and successfully seized the Assyrian throne. The surrender of the army indicates that the usurper was an Assyrian and possibly even a member of the royal family, or at least a person that would be acceptable as king.[13] Sinsharishkun then abandoned his Babylonian campaign and though he successfully defeated the usurper after a hundred days of civil war, the absence of the Assyrian army saw the Babylonians conquer the last remaining Assyrian outposts in Babylonia in 622–620 BC.[12] The Babylonian siege of Uruk had begun by October 622 BC and though control of the ancient city would shift between Assyria and Babylon, it was firmly under Babylonian rule by 620 BC.[14] and Nabopolassar consolidated his rule over the entirety of Babylonia.[15] During the next years, the Babylonians scored several other victories against the Assyrians and by 616 BC, Nabopolassar's forces had reached as far as the Balikh River. Pharaoh Psamtik I, Assyria's ally, marched his forces to help Sinsharishkun. The Egyptian pharaoh had over the last few years campaigned in order to establish dominance over the small city-states of the Levant and it was in his interests that Assyria survived as a buffer state between his own empire and those of the Babylonians and Medes in the east.[15] A joint Egyptian-Assyrian campaign to capture the city of Gablinu was undertaken in October of 616 BC, but ended in defeat after which the Egyptian allies kept to the west of the Euphrates, only offering limited support.[16] In 616 BC, the Babylonians defeated the Assyrian forces at Arrapha and pushed them back to the Little Zab.[17] Although Nabopolassar's attempt at taking Assur, the ceremonial and religious center of Assyria, in May of the next year failed and he retreated to Takrit, the Assyrians also failed to assault Takrit and put an end to him.[16]

Medes intervention

In October or November 615 BC, the Medes under King Cyaxares invaded Assyria and conquered the region around the city of Arrapha in preparation for a great final campaign against the Assyrians.[16] That same year, they defeated Sinsharishkun at the Battle of Tarbisu[1][17][18] and in 614 BC, they conquered Assur, plundering the city and killing many of its inhabitants after its capture.[1][17][19] Nabopolassar only arrived at Assur after the plunder had already begun and met with Cyaxares, allying with him and signing an anti-Assyrian pact. Shortly after, Sinsharishkun made his last attempt at a counterattack, rushing to rescue the besieged city of Rahilu, but Nabopolassar's army had retreated before a battle could take place.[20] In 612 BC, the Medes and Babylonians joined their forces to besiege Nineveh and after a lengthy and brutal siege, the city was taken by the allied forces,[21][20] the Medes playing the major part in the city's downfall.[22][23] Although Sinsharishkun's fate is not entirely certain, it is commonly accepted that he died in the defense of Nineveh.[24][25]

With the destruction of Assur in 614 BC, the traditional Assyrian coronation ritual was now impossible,[26] thus Ashur-uballit II did have a coronation in Harran and took this city as his capital. While the Babylonians saw him as the Assyrian king, the few subjects Ashur-uballit II governed himself probably did not share this view. Rather, Ashur-uballit's formal title was crown prince (mar šarri, literally meaning "son of the king").[27] However, Ashur-uballit not formally being king does not indicate that his claim to the throne was challenged, only that he had yet to go through with the traditional ceremony.[28] Ashur-uballit's main objective would have been to retake the Assyrian heartland, including Assur and Nineveh. Bolstered by the forces of his allies, Egypt and Mannea, this goal was probably seen as quite possible and his rule at Harran and role as crown prince (and not legitimately crowned king) probably seemed like a mere temporary retreat. Instead, Ashur-uballit's rule at Harran composes the final years of the Assyrian Empire, which at this point, had effectively ceased to exist.[2][28][29] After Nabopolassar himself had travelled the recently conquered Assyrian heartland in 610 BC in order to ensure stability, the Medo-Babylonian army embarked on a campaign against Harran in November of 610 BC.[29] Intimidated by the approach of the Medo-Babylonian army, Ashur-uballit and a contingent of Egyptian reinforcements fled the city into the deserts of Syria.[30][31] The siege of Harran lasted from the winter of 610 BC to the beginning of 609 BC and the city eventually capitulated.[32] Ashur-uballit's failure at Harran marks the end for the ancient Assyrian monarchy, which would never be restored.[33]

After the Babylonians had ruled Harran for three months, Ashur-uballit and a large force of Egyptian soldiers attempted to retake the city, but this campaign failed disastrously.[30][34] Beginning in July or June 609 BC, Ashur-uballit's siege lasted for two months, until August or September, but he and the Egyptians retreated when Nabopolassar again led his army against them. It is possible that they had retreated even earlier.[34]

Aftermath

The eventual fate of Ashur-uballit is unknown[30] and his siege of Harran in 609 BC is the last time he, or the Assyrians in general, are mentioned in Babylonian records.[34] After the battle at Harran, Nabopolassar resumed his campaign against the remainder of the Assyrian army in the beginning of the year 608 or 607 BC. It is thought that Ashur-uballit was still alive at this point, for in 608 BC the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II, Psamtik I's successor, personally led a large Egyptian army into former Assyrian territory to rescue his ally and turn the tide of the war. Because there is no mention of a large battle between the Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians and Medes in 608 BC (a battle between the four greatest military powers of their day is unlikely to have been forgotten and left out of contemporary sources) and no later mentions of Ashur-uballit, it is possible that he died at some point in 608 BC before his allies and his enemies could clash in battle.[30] M.B. Rowton speculates Ashur-uballit could have lived until 606 BC,[30] but by then the Egyptian army is mentioned in Babylonian sources without any references to the Assyrians or their king.[26]

Although Ashur-uballit is no longer mentioned after 609 BC, the Egyptian campaigns in the Levant continued for some time until a crushing defeat at the battle of Carchemish in 605 BC. Throughout the next century, Egypt and Babylon, brought into direct contact with each other through Assyria's fall, would frequently be at war with each other over control in the Fertile Crescent.[34]

The rapid collapse of Assyrian power remains a great mystery, but it's clear that the Medes played a role in it.[35]

Notes

- It is also possible that Nabopolassar was an ally of Sin-shumu-lishir in the previous revolt and merely continued his rebellion, but this theory requires more assumptions without any concrete evidence.[9]

References

- Liverani 2013, p. 539.

- Frahm 2017, p. 192.

- Curtis 2009, p. 37.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 121.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 255.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 129.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 126.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 13.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 256.

- Beaulieu 1997, p. 386.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 14.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 15.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 263.

- Boardman 1992, p. 62.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 16.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 17.

- Boardman 2008, p. 179.

- Bradford 2001, p. 48.

- Potts 2012, p. 854.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 18.

- Frahm 2017, p. 194.

- Dandamayev & Grantovskiĭ 1987, pp. 806-815.

- Dandamayev & Medvedskaya 2006.

- Yildirim 2017, p. 52.

- Radner 2019, p. 135.

- Reade 1998, p. 260.

- Radner 2019, pp. 135–136.

- Radner 2019, pp. 140–141.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 19.

- Rowton 1951, p. 128.

- Bassir 2018, p. 198.

- Bertman 2005, p. 19.

- Radner 2019, p. 141.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 20.

- Edwards 1970, p. 14.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Sami Said (3 December 2018). Southern Mesopotamia in the time of Ashurbanipal. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-139617-0.

- Bassir, Hussein (2018). "The Egyptian expansion in the near east in the saite period" (PDF). Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences. 3 (2): 196–200.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1997). "The Fourth Year of Hostilities in the Land". Baghdader Mitteilungen. 28: 367–394.

- Bertman, Stephen (14 July 2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-518364-1.

- Boardman, John (16 January 1992). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22717-9.

- Boardman, John (28 March 2008). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 3, Part 2, The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.

- Bradford, Alfred S. (2001). With Arrow, Sword, and Spear: A History of Warfare in the Ancient World. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-95259-4.

- Curtis, Adrian (16 April 2009). Oxford Bible Atlas. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-162332-5.

- Dandamayev, M.; Grantovskiĭ, È. (1987). "ASSYRIA i. The Kingdom of Assyria and its Relations with Iran". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 8. pp. 806–815.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dandamayev, M.; Medvedskaya, I. (2006). "MEDIA". Encyclopaedia Iranica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen (1970). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6.

- Frahm, Eckart (12 June 2017). A Companion to Assyria. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3593-4.

- Lipschits, Oded (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah Under Babylonian Rule. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-095-8.

- Liverani, Mario (4 December 2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9.

- Na’aman, Nadav (1991). "Chronology and History in the Late Assyrian Empire (631—619 B.C.)". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie. 81: 243–267.

- Potts, Daniel T. (15 August 2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-6077-6.

- Radner, Karen (2019). "Last Emperor or Crown Prince Forever? Aššur-uballiṭ II of Assyria according to Archival Sources". State Archives of Assyria Studies. 28: 135–142.

- Reade, J. E. (1998). "Assyrian eponyms, kings and pretenders, 648-605 BC". Orientalia (NOVA Series). 67 (2): 255–265. JSTOR 43076393.

- Rowton, M. B. (1951). "Jeremiah and the Death of Josiah". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 2 (10): 128–130. doi:10.1086/371028.

- Yildirim, Kemal (2017). "Diplomacy in Neo-Assyrian Empire (1180-609) Diplomats in the Service of Sargon II and Tiglath-Pileser III, Kings of Assyria". International Academic Journal of Development Research. 5 (1): 128–130.