Mauro-Roman Kingdom

The Mauro-Roman Kingdom (Latin: Regnum Maurorum et Romanorum) was an independent Christian Berber kingdom centered on the city of Altava which controlled much of the ancient Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis, located in present-day northern Algeria. The kingdom was first formed in the fifth century as Roman control over the province weakened and Imperial resources had to be concentrated elsewhere, notably in defending the Italian Peninsula itself from invading Germanic tribes.

Kingdom of the Moors and Romans Regnum Maurorum et Romanorum | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 477–578 | |||||||||||||||||

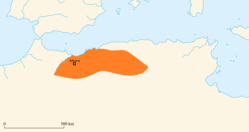

The approximate extent of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom prior to its collapse after the defeat of Garmul. | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Altava | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Berber, African Romance Latin | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||

• c. 477–508 | (unknown) | ||||||||||||||||

• c. 508–535 | Masuna | ||||||||||||||||

• 535–541 | Mastigas | ||||||||||||||||

• 541–545 | Stotzas | ||||||||||||||||

• 545–546 | John | ||||||||||||||||

• 546 – c. 570 | (unknown) | ||||||||||||||||

• c. 570 – 578 | Garmul | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late antiquity | ||||||||||||||||

• Separation from the Western Roman Empire | 429 | ||||||||||||||||

• Death of Gaiseric | 477 | ||||||||||||||||

• Collapse and partial re-incorporation into the Roman Empire | 578 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Algeria |

|

|

Prehistory

|

|

|

|

Modern times Ottoman Algeria (16th - 19th centuries)

French Algeria (19th - 20th centuries)

|

|

Contemporary era |

|

Related topics

|

The rulers of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom would repeatedly come into conflict with the Vandals of the neighbouring Vandalic Kingdom, which had been established following the Vandalic conquest of the Roman province of Africa. King Masuna of the Moors and Romans would ally with the armies of the Eastern Roman Empire during their reconquest of Northern Africa in the Vandalic War. Following the Eastern Roman victory over the Vandals, the Mauro-Roman Kingdom would maintain its alliance with the Eastern Roman Empire, assisting it in wars against invading Berbers of other tribes and kingdoms, such as the Kingdom of the Aures.

Eventually, the diplomatic ties between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Mauro-Roman Kingdom would break down. King Garmul would invade the Eastern Roman Praetorian Prefecture of Africa in an attempt at capturing Roman territories. His defeat in 578 AD led almost immediately to the end of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom, which was fragmented and partially reincorporated into the Roman Empire.

The kingdom was succeeded by some smaller romanized Berber successor states, such as the Kingdom of Altava. These petty kingdoms would last in the Maghreb until the conquest of the region by the Umayyad Caliphate in the seventh and eighth centuries.

History

Background

.svg.png)

Mauretania and western Numidia, previously a Roman client kingdom, were fully annexed by the Roman Empire in 40 AD and divided into two provinces under Emperor Claudius; Mauretania Tingitana ("Tangerine Mauretania") and Mauretania Caesariensis ("Caesarian Mauretania"), with the separating border designated as Moulouya River.[1]

Northern Africa was not as well-defended as frontiers that saw frequent attacks, such as those against Germania and Persia, but the economic importance of the African provinces made them important to retain. To this end, defensive structures were constructed alongside their borders, such as the Fossatum Africae; a 750 km long linear defensive structure composed of ditches, stone walls and other fortifications. This structure would be in consistent use until the Vandal conquest of the province of Africa.[2] The Mauretanian frontier, not as well defended as that of the African frontier, was known as the Limes Mauretaniae.[3]

As Roman authority became occupied elsewhere during the disastrous civil wars and disintegrations of the Crisis of the Third Century, local nomadic Berber tribes harassed settlements and occupied some of the border regions of Mauretania Tingitania and Mauretania Caesariensis. The incursions were seen as such a large threat that the Western Roman Emperor, Maximian, personally became involved in the conflict.[4] Three Berber tribes, the Bavares, Quinquegentiani and Fraxinenses, had formed a confederation. Though the Berbers faced a defeat against a small army raised by the governor of Mauretania Caesariensis in 289 AD, they soon returned. In 296 AD, Maximian raised an army, from Praetorian cohorts, Aquileian, Egyptian, and Danubian legionaries, Gallic and German auxiliaries, and Thracian recruits, advancing through Spain that autumn.[5] He may have defended the region against raiding Berbers before crossing the Strait of Gibraltar into Mauretania Tingitana to protect the area from Frankish pirates.[4]

Maximian began an offensive against the invading tribes in March 297 AD, and pursued them even beyond the borders of the Empire, not content with simply letting them return to their homelands in the Atlas Mountains, from which they would be able to continue to wage war. Though the Berbers were skilled at guerrilla warfare and the terrain was unfavorable, Maximian continued his campaign deep into Berber territory. When the campaign was concluded in 298 AD, Maximian had driven the tribes back into the Sahara, devastated previously secure land and killed as many as he could.[6][7] On March 10, he made a triumphal entry into Carthage, with the people hailing him as redditor lucis aeternae ("restorer of the eternal light").[6][7]

Establishment

.jpg)

The fifth century would see the collapse and fall of the Western Roman Empire. The inland territories of Mauretania had already been under Berber control since the fourth century, with direct Roman rule confined to coastal cities such as Septem in Mauretania Tingitania and Caesarea in Mauretania Caesariensis.[8] The Berber rulers of the inland territories maintained a degree of Roman culture, including the local cities and settlements, and often nominally acknowledged the suzerainty of the Roman Emperors.[9]

As barbarian incursions became more common even in previously secure provinces such as Italy, the Western Roman military became increasingly occupied to defend territories in the northern parts of the Empire. Even the vital Rhine frontier against Germania had been stripped of troops in order to organize a defense against a Visigothic army invading Italy under Alaric. The undermanned frontier allowed several tribes, such as the Vandals, Alans and Suebi, to cross the Rhine in 406 AD and invade Roman territory.[10] As attention was needed elsewhere, central authority began to collapse in many of the more distant provinces.

In 423, there was a powerful uprising of the Berbers of Mauritania and Numidia, which was suppressed only with great difficulty by Count Boniface in 427. In 429, however, Vandals and Alans led by Gaiseric invaded Mauritania from Hispania. The Berbers supported them, causing Roman rule to disappear from the province by 439. At the same time, it enabled the Romanized Berbers to form an independent state with their capital in Altava.

In Mauretania, local Berber leaders and tribes had long been integrated into the imperial system as allies, foederati and frontier commanders and as Roman control weakened, they established their own kingdoms and polities in the region. The presence of romanized communities along the frontier regions of the provinces meant that the Berber chieftains had some experience in governing populations composed of both Berbers and Romans.[11] Following the final collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Mauro-Roman Kingdom would grow into a fully fledged Barbarian kingdom not entirely unlike those that had sprung up in other parts of the former Empire. Though most other Barbarian kingdoms, such as those of the Visigoths and Vandals, were fully within the borders of the former Roman Empire, the Mauro-Roman Kingdom extended beyond the formal imperial frontier, also encompassing Berber territories never controlled by the Romans.[11]

According to the Eastern Roman historian Procopius, the Moors only began to truly expand and consolidate their power following the death of the powerful vandal king Gaiseric in 477 AD, after which they won many victories against the Vandal kingdom and established more or less full control over the former province of Mauretania. Having feared Gaiseric, the Moors under Vandal control revolted against his successor Huneric following his attempt to convert them to Arian Christianity and the harsh punishments incurred on those who did not convert. In the Aurès Mountains, this led to the foundation of the independent Kingdom of the Aures, which was fully independent by the time of Huneric's death in 484 AD and would never again come under Vandal rule. Under the rule of Huneric's successors Gunthamund and Thrasamund, the wars between the Berbers and the Vandals continued. During Thrasamund's reign, the Vandals suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of a Berber king ruling the city Tripolis, named Cabaon, who almost completely destroyed a Vandal army that had been sent to subjugate the city.[12]

Kings of the Moors and Romans

One of the Berber rulers of Mauretania, Masuna, titled himself as Rex gentium Maurorum et Romanorum, the "King of the Roman and Moorish peoples". Masuna is known only from an inscription on a fortification in Altava (modern Ouled Mimoun, in the region of Oran), dated 508 AD. He is known to have possessed Altava, assumed to have been the capital due to its prominence under subsequent kings, and at least two other cities, Castra Severiana and Safar, as mention is made of officials he appointed there. As the seat of an ecclesiarchal diocese (the diocese of Castra Severiana, an ancient bishophoric which flourished during Late Antiquity), the control of Castra Severiana may have been particularly important.[13]

- In full, the inscription reads: "Pro sal(ute) et incol(umitate) reg(is) Masunae gent(ium) Maur(orum) et Romanor(um) castrum edific(atum) a Masgivini pref(ecto) de Safar. Iidir proc(uratore) castra Severian(a) quem Masuna Altava posuit, et Maxim(us) pr(ocurator) Alt(ava) prefec(it). P(ositum) p(rovinciae) CCCLXVIIII". The three officials appointed are Masgiven (prefect of Safar), Lidir (procurator of Castra Severiana) and Maximus (procurator of Altava). The date, 469, is the provincial founding date and would correspond to 508 AD.[14][15]

The core administrative centers of the kingdom were located on the territorial interface of two distinct populations, the coastal and settled provincial Romani (Romans) and the tribal Mauri (Moors, or Berbers) situated around and beyond the former Roman frontier.[11] The citizens of the Roman cities were subjects of a formal and organized administration headed by appointed officials, such as those appointed by King Masuna. The military manpower was derived from the Berber tribes over which control was maintained through the control of key individuals, such as tribal leaders, by issuing honors and estates to them.[11] As the Mauro-Roman Kingdom adopted the military, religious and sociocultural organization of the Roman Empire, it continued to be fully within the Western Latin world. The administrative structure and titulature used by the rulers of the kingdom suggests a certain romanized political identity in the region.[16] This Roman political identity was maintained by other smaller Berber kingdoms in the region as well, such as in the Kingdom of the Aures where King Masties claimed the title of Imperator during his rule around 516 AD, postulating that he had not broken trust with either his Berber or Roman subjects.[17]

The Eastern Roman Empire and the Vandals

Eastern Roman records referring to the Vandal Kingdom, which had occupied much of the old Roman province of Africa and coastal parts of Mauretania, often refer to it with regards to a trinity of peoples; Vandals, Alans and Moors, and though some Berbers had assisted the Vandals in their conquests in Africa, Berber expansion was as previously stated more often than not focused against the Vandals rather than with them, which would lead to some expansion of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom and other Berber kingdoms of the region, such as the Kingdom of the Aures.[18]

Indeed, a Berber king identified by the historian Procopius of the Eastern Roman Empire as "Massonas" (often assumed to be the same person as Masuna) allied with the forces of the Eastern Roman Empire in 535 AD against the Vandal Kingdom during the Vandalic War.[19] When Belisarius and the Eastern Roman forces arrived in Northern Africa to invade and restore Roman rule over the region, local Berber rulers willingly submitted to Imperial rule, only demanding in return the symbols of their offices; a silver crown, a staff of silver gilt, a tunic and gilded boots. Essentially client kings, many of the Berber rulers would prove recalcitrant. Those rulers that were not directly adjacent to Imperial territories were more or less independent, though nominally still Imperial subjects, and were treated with larger amounts of courtesy than the ones directly bordering the Empire, as to keep them in line.[20]

Gelimer, the final Vandal king, attempted to recruit the Berber kingdoms to fight for him but very few Berber troops took part in fighting for the Vandal side. Though the Vandals had supplied the Berber kings with symbols of their offices similar to those supplied by the Romans, the Berber kings did not consider the Vandals to hold that power securely. During the Vandalic war, most Berber rulers waited out the conflict in order to avoid fighting for the losing side.[17]

Following the Eastern Roman re-conquest of the Vandal Kingdom, the local governors began to experience problems with the local Berber tribes. The province of Byzacena was invaded and the local garrison, including the commanders Gainas and Rufinus, was defeated. The newly appointed Praetorian Prefect of Africa, Solomon, waged several wars against these Berber tribes, leading an army of around 18,000 men into Byzacena. Solomon would defeat them and return to Carthage, though the Berbers would again rise and overrun Byzacena. Solomon would once again defeat them, this time decisively, scattering the Berber forces. Surviving Berber soldiers retreated into Numidia where they joined forces with Iabdas, King of the Aures.[21][22]

Masuna, allied with the Eastern Empire, and another Berber king, Ortaias (who ruled a kingdom in the former province of Mauretania Sitifensis),[23] urged Solomon to pursue the enemy Berbers into Numidia, which he did. Solomon did not engage Iabdas in battle however, distrusting the loyalty of his allies, and instead constructed a series of fortified posts along the roads linking Byzacena with Numidia.[24][22]

Masuna died around 535 AD and was succeeded as king by Mastigas (also known as Mastinas). Procopius states that Mastigas was a fully independent ruler who ruled almost the entire former province of Mauretania Caesariensis, except for the former provincial capital, Caesarea, which had been under control of the Vandals and was in Eastern Roman hands during his time.[25] The rulers of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom, and other Berber kingdoms, continued to regard themselves as subjects of the Eastern Roman Emperor in Constantinople, even when they were at war with him or engaged in raids of Imperial territory, most Berber rulers using titles such as dux or rex.[23]

Collapse

The last recorded king was Garmul (also known as Garmules) who would resist Eastern Roman rule in Africa.[26] In the late 560s, Garmul launched raids into Roman territory, and although he failed to take any significant town, three successive generals, Praetorian prefect Theodore (in 570 AD) and the two magistri militum Theoctistus (in 570 AD) and Amabilis (in 571 AD), are recorded by the Visigoth historian John of Biclaro to have been killed by Garmul's forces.[27] His activities, especially when regarded together with the simultaneous Visigoth attacks in Spania, presented a clear threat to the province's authorities. Garmul was not the leader of a mere semi-nomadic tribe, but of a fully-fledged barbarian kingdom, with a standing army. Thus, the new Eastern Roman emperor, Tiberius II Constantine, re-appointed Thomas as praetorian prefect of Africa, and the able general Gennadius was posted as magister militum with the clear aim of reducing Garmul's kingdom. Preparations were lengthy and careful, but the campaign itself, launched in 577–78 AD, was brief and effective, with Gennadius utilizing terror tactics against Garmul's subjects. Garmul was defeated and killed in 578 AD.[28]

With the defeat of Garmul, the Mauro-Roman Kingdom collapsed. The Eastern Roman Empire re-incorporated some of the territory of the Kingdom, notably the coastal corridor of the old provinces of Mauretania Tingitania and Mauretania Caesariensis.[28]

Legacy

Altava remained the capital of a romanized Berber kingdom, though the Kingdom of Altava was significantly smaller in size than the Kingdom of Masuna and Garmul had been.[29] In the late fifth and early sixth century, Christianity grew to be the fully dominant religion in the Berber Altava kingdom, with syncretic influences from the traditional Berber religion. A new church was built in the capital Altava in this period.[30] Altava and the other successor kingdoms of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom, the Kingdoms of the Ouarsenis and the Hodna, also saw an economical rise and the construction of several new churches and fortifications. Though the Eastern Roman Praetorian Prefecture of Africa and the later Exarchate of Africa would see some further Berber rebellions, these would be put down and many Berber tribes would be accepted as foederati, as they had been many times in the past.[11]

The last known romanized Berber King to rule from Altava was Kusaila. He died in the year 690 AD fighting against the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb. He was also leader of the Awraba tribe of the Berbers and possibly Christian head of the Sanhaja confederation. He is known for having led an effective Berber martial resistance against the Umayyad Caliphate's conquest of the Maghreb in the 680s. In 683 AD Uqba ibn Nafi was ambushed and killed in the Battle of Vescera near Biskra by Kusaila, who forced all Arabs to evacuate their just founded Kairouan and withdraw to Cyrenaica.[31] But in 688 AD Arab reinforcements from Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan arrived under Zuhair ibn Kays. Kusaila met them in 690 AD, with the support of Eastern Roman troops, at the Battle of Mamma. Vastly outnumbered, the Awraba and Romans were defeated and Kusaila was killed.[32]

With the death of Kusaila, the torch of resistance passed to a tribe known as the Jerawa tribe, who had their home in the Aurès Mountains: his Christian Berber troops after his death fought later under Kahina, the queen of the Kingdom of the Aures and the last ruler of the romanized Berbers.[32]

List of Mauro-Roman kings

| Monarch | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown ruler(s) | The earliest recorded ruler of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom is Masuna, first recorded in inscriptions dated to 508 AD. | |

| Masuna | c. 508 – 535 | Also known as Massonas. Allied with the Eastern Roman Empire against the Vandal Kingdom and later against a Berber alliance gathered by the Kingdom of the Aures.[19][24][22] |

| Mastigas | 535–541 | Also known as Mastinas. Controlled virtually the entire ancient province of Mauretania Caesariensis, except for the old capital of Caesarea.[25] |

| Stotzas | 541–545 | Also known as Stutias. A former Eastern Roman rebel that allegedly became Mauro-Roman King after marriage with the daughter of a previous king. Was defeated and killed by Eastern Roman forces in 545 AD.[33][34] |

| John | 545–546 | Referred to as John the Tyrant and nicknamed Stotzas Junior ("Stotzas the Younger"), replaced Stotzas as ruler of his forces.[35] Was captured and sent in chains to Constantinople, where he is said to have been crucified.[36] |

| Unknown ruler(s) | No rulers recorded between 546 and the 570s. | |

| Garmul | c. 570 – 578 | Also known as Garmules. Invaded the Eastern Roman provinces in Northern Africa in the 570s. His death and defeat in 578 marks the end of the Mauro-Roman Kingdom, which was fragmented and partially reincorporated into the Roman Empire.[28] |

See also

- Western Roman Empire

- Eastern Roman Empire

- Barbarian Kingdoms

- Exarchate of Africa

References

Citations

- Talbert 2000, p. 457.

- Baradez 1949, p. 162.

- Frank 1959, p. 68.

- Barnes 1981, p. 16.

- Barnes 1982, p. 59.

- Odahl 2004, p. 58.

- Williams 1997, p. 75.

- Wickham 2005, p. 18.

- Wickham 2005, p. 335.

- Heather 2005, p. 195.

- Merrills 2017.

- Procopius.

- Morcelli 1816, p. 130.

- Graham 1902, p. 281.

- Conant 2004, pp. 199–224.

- Conant 2012, p. 280.

- Rousseau 2012.

- Wolfram 2005, p. 170.

- Martindale 1980, p. 734.

- Grierson 1959, p. 127.

- Martindale 1992, p. 1171.

- Bury 1958, p. 143.

- Grierson 1959, p. 126.

- Martindale 1992, p. 1172.

- Martindale 1992, p. 851.

- Aguado Blazquez 2005, p. 46.

- Martindale 1992, p. 504.

- Aguado Blazquez 2005, pp. 45–46.

- Martindale 1980, pp. 509–510.

- Lawless 1969.

- Conant 2012, pp. 280–281.

- Talbi 1971, pp. 19–52.

- Martindale 1992, p. 1200.

- Grierson 1959, p. 128.

- Sarantis 2016, p. 16.

- Martindale 1992, pp. 643-644.

Bibliography

Ancient

- Procopius (545). "Book III-IV: The Vandalic War (pts. 1 & 2)". History of the Wars.

Modern

- Aguado Blazquez, Francisco (2005). El Africa Bizantina: Reconquista y ocaso (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baradez, Jean (1949). Fossatum Africae. Recherches Aériennes sur l'organisation des confins Sahariens a l'Epoque Romaine. Arts et Métiers Graphiques.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barnes, Timothy David (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674165311.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barnes, Timothy David (1982). The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-7837-2221-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bury, John Bagnell (1958). History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian, Volume 2. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20399-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Camps, Gabriel (1995). "Djedar". In Gabriel Camps (ed.). Encyclopedie Berbere. 16. Editions Edisud. pp. 2409–2422.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conant, Jonathan (2004). Literacy and Private Documentation in Vandal North Africa: The Case of the Albertini Tablets within Merrills, Andrew (2004) Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-4145-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conant, Jonathan (2012). Staying Roman: Conquest and Identity in Africa and the Mediterranean, 439–700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107530720.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Courtot, P. (1987). "Altava". In Gabriel Camps (ed.). Encyclopedie Berbere. 4. Editions Edisud. pp. 543–552. ISBN 978-2-85744-282-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frank, Tenney (1959). An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome, Volume 4. Pageant Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Graham, Alexander (1902). Roman Africa: An Outline of the History of the Roman Occupation of North Africa, Based Chiefly Upon Inscriptions and Monumental Remains in that Country. Longmans, Green, and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grierson, Philip (1959). Matasuntha or Mastinas: a reattribution. The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. JSTOR 42662366.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heather, Peter (2005). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-98914-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lawless, R. (1969). Mauretania Caesariensis: an archaeological and geographical survey (PDF).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martindale, John Robert (1980). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume 2, AD 395–527. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521201599.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martindale, John Robert (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume 3, AD 527–641. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521201599.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merrills, Andrew (2017). Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138252684.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merrills, Andrew (2018). "The Moorish Kingdoms and the Written Record: Three 'Textual Communities' in Fifth- and Sixth-Century Mauretania". In Elina Screen, Charles West (ed.). Writing the Early Medieval West. Cambridge University. pp. 185–202. ISBN 9781107198395.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morcelli, Stefano Antonio (1816). Africa christiana, Volume I. Brescia.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Odahl, Charles Matson (2004). Constantine and the Christian Empire. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17485-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reynolds, Paul (2010). Trade in the western Mediterranean, AD 400–700, 439–700. University of Michigan: Tempus Reparatum. ISBN 0860547825.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rousseau, Philip (2012). A Companion to Late Antiquity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-405-11980-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarantis, Alexander (2016). Justinian and Africa, 533–548. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Battles.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Talbert, Richard J.A. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691049458.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Talbi, Mohammed (1971). Un nouveau fragment de l'histoire de l'Occident musulman (62–196/682–812): l'épopée d'al Kahina. Cahiers de Tunisie vol. 19. pp. 19–52.CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wickham, Chris (2005). Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean, 400–800. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921296-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Stephen (1997). Diocletian and the Roman Recovery. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-91827-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolfram, Herwig (2005). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520244900.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)