Mark 12

Mark 12 is the twelfth chapter of the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It continues Jesus' teaching in Jerusalem during his third visit to the Temple (traditionally identified with Holy Tuesday), it contains the parable of the Wicked Husbandmen, Jesus' argument with the Pharisees and Herodians over paying taxes to Caesar, and the debate with the Sadducees about the nature of people who will be resurrected at the end of time. It also contains Jesus' greatest commandment, his discussion of the messiah's relationship to King David, condemnation of the teachers of the law, and his praise of a poor widow's offering.

| Mark 12 | |

|---|---|

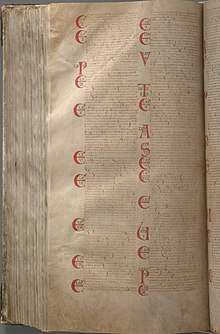

The Latin text of Mark 11:10–14:32 in Codex Gigas (13th century) | |

| Book | Gospel of Mark |

| Category | Gospel |

| Christian Bible part | New Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 2 |

| Gospel of Mark |

|---|

Text

The original text was written in Koine Greek. This chapter is divided into 44 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter are:

- Codex Vaticanus (325-350; complete)

- Codex Sinaiticus (330-360; complete)

- Codex Bezae (~400; complete)

- Codex Alexandrinus (400-440; complete)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (~450; extant verses 1-29)

Old Testament references

Parable of the wicked husbandmen

Jesus, after his argument with the chief priests of the Sanhedrin over his authority in Mark 11, tells "them" ("the chief priests, the scribes, and the elders") [2] several parables, of which Mark relates only one:

- A certain man planted a vineyard, and set an hedge about it, and digged a place for the winefat, and built a tower, and let it out to husbandmen, and went into a far country. And at the season he sent to the husbandmen a servant, that he might receive from the husbandmen of the fruit of the vineyard. And they caught him, and beat him, and sent him away empty.

- And again he sent unto them another servant; and at him they cast stones, and wounded him in the head, and sent him away shamefully handled. And again he sent another; and him they killed, and many others; beating some, and killing some.

- Having yet therefore one son, his wellbeloved, he sent him also last unto them, saying, They will reverence my son. But those husbandmen said among themselves, This is the heir; come, let us kill him, and the inheritance shall be ours. And they took him, and killed him, and cast him out of the vineyard.

- What shall therefore the lord of the vineyard do? he will come and destroy the husbandmen, and will give the vineyard unto others. And have ye not read this scripture; The stone which the builders rejected is become the head of the corner: This was the Lord's doing, and it is marvellous in our eyes? (1-11 KJV)

The scripture mentioned is a quotation from Psalm 118:22-23, the processional psalm for the three pilgrim festivals which also provided the source for the crowd's acclamation as Jesus entered Jerusalem, Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.[3] The quote about the stone is from the Septuagint version of the Psalms, a version Jesus and Jews in Israel would probably not have used. Mark however, who clearly has the Septuagint as his Old Testament reference, may have simply used it for his audience, as they spoke Greek, or to clarify his sources, oral and/or written. For those who believe the accuracy of Mark, these predictions serve to demonstrate the power of Jesus' knowledge. Paul also refers to Jesus as a "stone" in Romans 9:33 but references this with quotes from Isaiah 8:14 and 28:16. Acts of the Apostles 4:11 records Peter as using the same Psalm to describe Jesus. 1 Peter references both Isaiah and the Psalm in 2:6-8, although most scholars, though not all, do not accept this letter as actually written by the Apostle Peter.

Anglican Bishop Tom Wright contrasts this parable with Jesus' first parable recorded in Mark, the parable of the sower (Mark 4:1-20). In that parable, "one let of seed failed, then another, and another but at last there was a harvest", whereas in this parable, one slave is sent, then another, but when the final messenger comes, the vineyard owner's son, "he is ignominiously killed".[4]

Mark says the priests realized Jesus was speaking about them and wanted to arrest him but would not because of the people around. Mark therefore explicitly states the husbandmen to be the priests and teachers, and perhaps the Judean authorities in general. It could also be a metaphor for all of humanity. Most modern translations use the term "tenants", renters, instead of husbandmen. The owner is God. A common interpretation of the servants is that of the prophets or all of God's proceeding messengers, while the gentiles, or Christians, are the "others" who will be given the vineyard. (Brown 143) The vineyard is Israel or more abstractly the promise made to Abraham by God. The "son" is Jesus. "Beloved" is what God has called Jesus in Mark 1 and 9 during his baptism and the Transfiguration.

Isaiah 5 uses similar language regarding God's vineyard. Workers working the estates of absentee landlords happened frequently in the Roman Empire, making the story relevant to the listeners of the time. (Brown et al. 621) Vineyards were the source of grapes and wine, a common symbol of good in the Gospels. There is Jesus turning water into wine in John 2 and the saying about new wineskins in Mark 2:22. Natural growth, like Jesus' parables of The Mustard Seed and Seed Growing Secretly in Mark 4, was probably a naturally understood metaphor for Mark's audience as the ancient world was largely an agricultural world. The parable is also found in the Gospel of Thomas saying 65-66.

Paying taxes to Caesar

The chief priests sent some Pharisees and Herodians to Jesus. They offer false praise and hope to entrap him by asking him whether one should pay the taxes to the Romans. These two groups were antagonists, and by showing them working together against Jesus, Mark shows the severity of the opposition to him. Mark has mentioned them working together before in 3:6. The Herodians, supporters of Herod Antipas, would have been in Jerusalem with Herod during his trip there for the Passover.[5] Jesus asked them to show him a denarius, a Roman coin, and asks whose image and inscription are on it. The coin was marked with Caesar's image. Jesus then says "Give to Caesar what is Caesar's and to God what is God's" (17). Jesus thus avoids the trap, neither endorsing the Herodians and the Romans they supported, nor the Pharisees.

This same incident with small differences is also recorded in the Gospels of Matthew (22:15-22[6]) and Luke (20:20-26). Luke's Gospel makes clear "They hoped to catch Jesus in something he said, so that they might hand him over to the power and authority of the governor." Apparently, his interrogators anticipated that Jesus would denounce the tax. The charge of advocating non-payment of taxes was later leveled against Jesus before Pilate.

Giving God what is God's might be an admonishment to meet one's obligation to God as one must meet them to the state. (Brown et al. 622) It could also be Jesus' way of saying that God, not Rome, controlled Israel, indeed the whole world, and thereby also satisfy the Pharisees. This passage is often used in arguments on the nature of Separation of church and state.

The same saying is found in the Gospel of Thomas as saying 100, but adds the final statement "...and give me what is mine."

Some writers cite this phrase in support of tax resistance: see, for example, Ned Netterville,[7] Darrell Anderson,[8] and Timmothy Patton.[9]

The resurrection and marriage

Jesus' opponents now switch to the Sadducees, who deny the idea of the resurrection of the dead. The Sadducees only accepted the five books of the Torah as divinely inspired. The Jewish Levirate law or Yibbum (Deuteronomy 25:5) states that if a man dies and his wife has not had a son, his brother must marry her. The Sadducees quote an example of a woman has had seven husbands in this manner: [if there were a resurrection], who would she be married to when they all are resurrected from the dead?

Jesus says they do not understand "the scriptures and the power of God",[10] and states that after the resurrection no one will be married, "...they will be like the angels in heaven. Now about the dead rising: have you not read in the book of Moses, in the account of the bush, how God said to him, 'I am (emphasis added) the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob'? He is not the God of the dead, but of the living. You are badly (or greatly) mistaken!" (25-27) The story of the burning bush is found in Exodus 3 i.e. within the biblical texts acknowledged by the Sadducees.

The belief in the resurrection of the dead was largely a fairly recent innovation in ancient Jewish thought, and Jesus defends the belief against the Sadducees, who consider it to be a false innovation.[11] He quotes God's statement to Moses on Mount Sinai made in the present tense about the patriarchs to show that God states them to be still in existence after their death, and thus that the doctrine of resurrection is present in the scripture from the beginning. Jesus concludes that the Sadducees "greatly err".[12] Protestant theologian Heinrich Meyer notes that the "short pithy words" of this assertion, Greek: πολὺ πλανᾶσθε (polu planasthe), do not need the additional words in the Textus Receptus, Greek: ὑμεῖς οὖν, humeis oun, "you therefore").[13]

So far in Mark's gospel, Jesus has raised a dead girl (Mark 5:41-42: see Daughter of Jairus) and has predicted his own death and resurrection, in 8:31 for instance, but has not discussed the nature of resurrection in depth. Jesus largely defends the belief here, perhaps indicating Mark's intended audience already knows it. Paul also describes bodily resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15, that it will be of a fundamentally different nature than people's current physical nature. Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas uses an argument for eternal life based on the fact that the non-living matter of dead food becomes the living matter of the body after a person has eaten it.[14] Philosophically the validity of Jesus' argument for the resurrection of the dead depends on the accuracy of the story of the burning bush, that is if God really did say that and meant it in that way existence is possible after death as God would never be wrong. The Pharisees also believed in the resurrection of the dead.

The greatest commandment

A nearby scribe who hears Jesus' answer to their question comes over [15] and asks Jesus what God's greatest commandment is. Jesus replies "The first of all the commandments is, Hear, O Israel (the Shema, a centerpiece of all morning and evening Jewish prayer services); The Lord our God is one Lord: And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength: this is the first commandment. And the second is like, namely this, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. There is none other commandment greater than these." (29-31 KJV)

Jesus here quotes Deuteronomy 6:4-5 and Leviticus 19:18. Putting these two commandments together linked by love, putting loving others on the same level as loving God, was one of Jesus' theological innovations. (Brown et al. 622) (See also Christianity and Judaism, Didache 1.2) The Jewish Encyclopedia article on Jesus argues this shows Jesus knew and approved of the Didache, in its Jewish form. Mark wrote this probably four decades after Jesus' death showing Christians still used Jewish prayer formats, this being in the form of daily prayers, at this period. (Brown 144) Most Early Christians saw Jesus' teachings as summing up the essence of Jewish theology as opposed to the religion's ritualistic components (Brown et al. 622). Paul uses the same quotation from Leviticus in Galatians 5:14 and Romans 13:9 as summing up the law. See also Hillel the Elder.

The man agrees and says keeping these commandments is better than making sacrifices, to which Jesus replies that the man is "not far from the kingdom of God" (34). This seems to be Jesus' triumph over his opponents (or agreement with the Pharisees) as Mark states that this was the last question they asked him. Being "not far" from God can be seen in the sense of close to knowledge of God. Others have seen "far" as actually referring to a spatial distance from God, maybe from Jesus himself. (Kilgallen 237)

Teaching the crowd

Jesus continues to teaches in the Temple. This probably took place along the Temple's eastern wall.[16]

After overcoming his opponents' traps, Jesus poses a question of his own. He asks the crowd "How is it that the teachers of the law say that the Christ is the son of David? David himself, speaking by the Holy Spirit, declared: 'The Lord [יְהֹוָה Yĕhovah] said to my Lord [אָדוֹן 'adown]: Sit at my right hand until I put your enemies under your feet.' David himself calls him 'Lord.' How then can he be his son?" (35-37) This is a quote from Psalm 110:1 [17], which was traditionally believed to have been written by David himself. This Psalm was used during the coronation of the ancient Kings of Israel and Judea.[18]

This passage has caused much debate. It is a promise made to David by God. The first Lord mentioned is God and the second Lord was believed by Jews and then later Christians to refer to the messiah. Since David is here calling the messiah Lord the messiah must be superior to David. Son was a term of submission as father was a term of authority, so one can not say that the messiah will be inferior to David by using the term son. (Kilgallen 238)

Is Jesus saying that the messiah is not David's biological heir, or that he is greater than only David's heir, that the Messiah's kingdom is far greater than merely an earthly successor to David's political kingdom? The messiah was to be from the house of David, as both Matthew and Luke use their genealogies of Jesus to show. Mark has no genealogy or virgin birth. Some have argued that this is Mark's way of explaining why Jesus, from such a poor family, could possibly be the messiah. Since most modern critical scholars reject the genealogies in Luke and Matthew, some have argued that Jesus did not claim descent from David, and this is thus Jesus' explanation of this. Mark however seems to state Jesus to be David's heir. Jesus was acclaimed as bringing the kingdom of David in Mark 11:10. Mark had the demons call him the Son of God in 3:11 and 5:7. Peter called him the Christ in Mark 8:29. Bartimaeus, the blind beggar whom Jesus healed, called him the Son of David in 10:47, although Jesus has not referred to himself in this manner directly, an interesting choice for Mark to make, fitting with his theme of the Messianic Secret. Jesus usually refers to himself as the Son of man. Jesus explicitly says he is the messiah and the "Son of the Blessed One" in 14:61-62 and perhaps tells Pilate he is the King of the Jews in 15:2: "He answered him, ‘You say so.’"(NRSV). Mark clearly wrote to show Jesus is the Jewish messiah prophesied to be David's heir and successor, so why this speech and no explicit statement by Jesus of Davidic descent? Is he simply saying that the messiah is superior to David, whether from his house or not? If the messiah is indeed God, as the Psalm was interpreted by some Early Christians, then his glory is greater than the glory of any one house.

Both Matthew and Luke use the same story, showing they did not think it contradicted their claim of descent from King David in Matthew 1 and Luke 3. Acts of the Apostles 2:34-35 has Peter use the same quote in reference to Jesus. Paul alludes to it in 1 Corinthians 15:25. Paul might also reference it as well in Colossians 3:1 and Romans 8:34 where he mentions "Christ" at the right hand of God. It is also found in Hebrews 1:13.

Jesus condemns the teachers of the law because of their wealth, fancy clothes, and self-importance. "They devour widows' houses and for a show make lengthy prayers. Such men will be punished most severely".[19] Mark 12:39 refers to "the important seats in the synagogue", although the setting for Jesus' teaching is in the temple. Some writers have used this passage to justify anti-semitism over the ages but Jesus is obviously criticizing their actions, not religion. The teachers would be analogous to lawyers today, as the Jewish religious code largely was the Jewish law. The scribes interpreted, as judges do today, the meaning of the laws. Often they might feign piety to gain access to trusteeship of a widow's estate and therefore its assets, like law firms today seek good reputations for the sole purpose of obtaining rich clients. The fact that Jesus states that they will be "punished", something which they have done to others, could show how the judges will be judged. (Brown et al. 623)

Widow's mite

Jesus goes to where people make offerings, throwing donations of money into the Temple treasury,[20] and praises a widow's donation, "...two very small copper coins, worth only a fraction of a penny" (42), in preference to the larger donations made by the rich. "I tell you the truth, this poor widow has put more into the treasury than all the others. They all gave out of their wealth; but she, out of her poverty, put in everything—all she had to live on." (43-44) She gives two lepta or mites, copper coins, the smallest denomination around. The widow is a literary foil to the rich who put far more into the treasury but give far less.[21] Jesus contrasts her offering as the greater sacrifice because it is all she had, as opposed to the offerings of the rich, who only gave what was convenient. Her total sacrifice might foreshadow Jesus' total sacrifice of his life (Brown et al. 623).

Mark uses the term kodrantēs, a Greek form of the Latin word quadrans, for penny, one of Mark's Latinisms which many take as evidence for composition in or near Rome.

Comparison with other canonical gospels

Matthew's gospel records most of the same content in 21:28-22:46 but with important differences: he adds the parables of the Two Sons and the Marriage of the King's Son into Jesus' discussion with the priests, but does not have Jesus telling the teacher he is not far from God, leaving the man in Matthew looking more hostile to Jesus than he is in Mark. Matthew has Jesus with a much more elaborate discourse condemning his opponents in 23 but no widow's offering and Jesus discusses David with the Pharisees, not the crowd.

Luke keeps the same sequence as Mark in 20:9-21:4 but also has slight differences. Jesus tells the parable of the husbandmen to all the people, not just the priests. Unnamed spies from the priests challenge Jesus about the taxes and there is a longer discourse on marriage. Luke does not have Jesus telling the teacher the greatest commandment. John skips from Jesus' teaching after his arrival in Jerusalem in John 12 to the Last Supper in chapter 13.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gospel of Mark - Chapter 12. |

- Kirkpatrick, A. F. (1901). The Book of Psalms: with Introduction and Notes. The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Book IV and V: Psalms XC-CL. Cambridge: At the University Press. p. 839. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Mark 11:27

- Mark 11:9-10

- Wright, T., (2001) Mark for Everyone, p. 158

- Kilgallen p. 228.

- http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew%2022:15-22&version=NIV

- https://web.archive.org/web/20111226043103/http://www.jesus-on-taxes.com/uploads/JesusMarch17th08-_2.pdf

- http://www.simpleliberty.org/giaa/render_unto_caesar.htm

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2018-12-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mark 12:24

- Miller, 42

- Mark 12:27

- Meyer, H. A. W., Meyer's NT Commentary on Mark 12, accessed 3 April 2020

- Gospel of Thomas, Saying 11, accessed 5 December 2017

- Or, "came up and heard them disputing". Interpretations differ as to whether the scribe heard the debate and came over, or came over and heard the debate.

- Kilgallen 238

- Original Hebrew

- Miller 43

- Mark 12:40

- Mark 12:41: Disciples' Literal New Testament

- James L. Resseguie, Narrative Criticism of the New Testament: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), 124.

Sources

- Brown, Raymond E., An Introduction to the New Testament Doubleday 1997 ISBN 0-385-24767-2

- Brown, Raymond E. et al., The New Jerome Biblical Commentary Prentice Hall 1990 ISBN 0-13-614934-0

- Kilgallen, John J., A Brief Commentary on the Gospel of Mark Paulist Press 1989 ISBN 0-8091-3059-9

- Miller, Robert J., editor, The Complete Gospels Polebridge Press 1994 ISBN 0-06-065587-9

External links

- Mark 12 King James Bible - Wikisource

- English Translation with Parallel Latin Vulgate

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Multiple bible versions at Bible Gateway (NKJV, NIV, NRSV etc.)

| Preceded by Mark 11 |

Chapters of the Bible Gospel of Mark |

Succeeded by Mark 13 |