Macarius of Egypt

Macarius of Egypt (Greek: Ὅσιος Μακάριος ο Ἀιγύπτιος, Osios Makarios o Egyptios; Coptic: ⲁⲃⲃⲁ ⲙⲁⲕⲁⲣⲓ; 300–391) was a Coptic Christian monk and hermit. He is also known as Macarius the Elder, Macarius the Great and The Lamp of the Desert.

Saint Macarius of Egypt | |

|---|---|

An icon of Saint Macarius of Egypt | |

| Monk | |

| Born | c. 300 Shabsheer (Shanshour), Al Minufiyah Governorate, Byzantine Egypt |

| Died | 391 Scetes, Byzantine Egypt |

| Venerated in | Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodox Churches Roman Catholic Church |

| Major shrine | Monastery of Saint Macarius the Great, Scetes, Egypt |

| Feast |

|

Life

St. Macarius was born in Lower Egypt. A late tradition places his birthplace in the village of Shabsheer (Shanshour), in Al Minufiyah Governorate, Egypt around 300 A.D. At some point before his pursuit of asceticism, Macarius made his living smuggling saltpeter in the vicinity of Nitria, a vocation which taught him how to survive in and travel across the wastes in that area.[1]

St. Macarius is known for his wisdom. His friends and close kin used to call him Paidarion Geron (Greek: Παιδάριον Γερών,which when compounded as Paidiogeron[2] led to Coptic: Ⲡⲓⲇⲁⲣ Ⲓⲟⲩⲅⲉⲣⲟⲛ, Pidar Yougiron) which meant the “old young man”, i.e. “the young man with the elders’ wisdom."[3]

At the wish of his parents Macarius entered into marriage, but was soon widowed.[4] Shortly after, his parents died as well. Macarius subsequently distributed all his money among the poor and needy. He found a teacher in an experienced Elder, who lived in the desert not far from the village. The Elder accepted the youth, guided him in the spiritual science of watchfulness, fasting and prayer, and taught him the handicraft of weaving baskets.[4] Seeing his virtues, the people of his village brought him to the bishop of Ashmoun who ordained him priest.

A while later, a pregnant woman accused him of having defiled her. Macarius did not attempt to defend himself, and accepted the accusation in silence. However, when the woman's delivery drew near, her labor became exceedingly difficult. She did not manage to give birth until she confessed Macarius's innocence. A multitude of people then came asking for his forgiveness, but he fled to the Nitrian Desert to escape all mundane glory.

As a hermit, Macarius spent seven years living on only pulse and raw herbs.[5] He spent the following three years consuming four or five ounces of bread a day and only one vessel of oil a year.[5] While at the desert, he visited Anthony the Great and learned from him the laws and rules of monasticism. When he returned to the Scetic Desert at the age of forty, the fame of his sanctity drew many followers. The community, which took up its residence in the desert, was of the semi-eremitical type. The monks were not bound by any fixed rule; their cells were close together, and they met for Divine worship only on Saturdays or Sundays. He presided over this monastic community for the rest of his life. Ten years after going into the desert, he became a priest.[6]

For a brief period of time, Macarius was banished to an island in the Nile by the Emperor Valens, along with Saint Macarius of Alexandria, during a dispute over the doctrine of the Nicene Creed. Both men were victims of religious persecution by the followers of then Bishop Lucius of Alexandria. During their time on the island, the daughter of a pagan priest had become ill. The people of the island believed that she was possessed by an evil spirit. Both saints prayed over the daughter, which in turn had saved her. The pagan people of the island were so impressed and grateful that they stopped their worship of the pagan gods and built a church. When word of this got back to the Emperor Valens and Bishop Lucius of Alexandria, they quickly allowed both men to return home. At their return on 13 Paremhat, they were met by a multitude of monks of the Nitrian Desert, numbered fifty thousand, among whom were Saint Pishoy and Saint John the Dwarf.

Death and relics

Macarius died in the year 391. After his death, the natives of his village of Shabsheer stole the body and built a great church for him in their village. Pope Michael V of Alexandria brought the relics of Saint Macarius back to the Nitrian Desert on 19 Mesori. Today, the body of Saint Macarius is found in his monastery, the Monastery of Saint Macarius the Great in Scetes, Egypt.

Attributed writings: the 50 Spiritual Homilies and Letters

Fifty Spiritual Homilies were ascribed to Macarius a few generations after his death, and these texts had a widespread and considerable influence on Eastern monasticism and Protestant pietism.[7] This was particularly in the context of the debate concerning the 'extraordinary giftings' of the Holy Spirit in the post-apostolic age, since the Macarian Homilies could serve as evidence in favour of a post-apostolic attestation of 'miraculous' Pneumatic giftings to include healings, visions, exorcisms, etc. The Macarian Homilies have thus influenced Pietist groups ranging from the Spiritual Franciscans (West) to Eastern Orthodox monastic practice to John Wesley to modern charismatic Christianity.

However, modern patristic scholars have established that it is not likely that Macarius the Egyptian was their author.[8] The identity of the author of these fifty Spiritual Homilies has not been definitively established, although it is evident from statements in them that the author was from Upper Mesopotamia, where the Roman Empire bordered the Persian Empire, and that they were not written later than 534.[9]

In addition to the homilies, a number of letters have been ascribed to Macarius. Gennadius (De viris illustribus 10) recognizes only one genuine letter of Macarius, which is addressed to younger monks. The first letter, called "Ad filios Dei," may indeed be the genuine letter by Macarius the Egyptian that is mentioned by Gennadius (Vir. Ill.10), but the other letters are probably not by Macarius. The second letter, the so-called "Great Letter" used the De instituto christiana of Gregory of Nyssa, which was written c. 390; the style and content of the "Great Letter" suggest that its author is the same anonymous Mesopotamian who wrote the fifty Spiritual Homilies.[10]

The seven so-called Opuscula ascetica edited under his name by Petrus Possinus (Paris, 1683) are merely later compilations from the homilies, made by Simeon the Logothete, who is probably identical with Simeon Metaphrastes (d. 950). The teachings of Macarius are characterized by a strong Pneumatic emphasis that closely intertwines the salvific work of Jesus Christ (as the 'Spirit of Christ') with the supernatural workings of the Holy Spirit. This 'Pneumatic' thrust in the Spiritual Homilies is often termed 'mystical' and as such is a spiritual mode of thought which has endeared him to Christian mystics of all ages, although, on the other hand, in his anthropology and soteriology he frequently approximates the standpoint of St. Augustine. Certain passages of his homilies assert the entire depravity of man, while others postulate free will, even after the fall of Adam, and presuppose a tendency toward virtue, or, in semi-Pelagian fashion, ascribe to man the power to attain a degree of readiness to receive salvation.

Legacy and monastery

Macarius is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches.

In the Methodist Churches, Macarius is regarded highly for writing on the topic of entire sanctification.[11]

Macarius of Egypt founded a monastery that bears his name, the Monastery of Saint Macarius the Great,[3] which has been continuously inhabited by monks since its foundation in the fourth century. St. Macarius’ face used to be enlightened with grace in an amazing way to the extent that many fathers testified that his face used to glow in the dark; and thus appeared his name as “the glowing lantern.” This description was transferred to his monastery, and thus it was called “the glowing lantern of the wilderness” or “the glowing monastery,” which meant the place of high wisdom and constant prayer.[3] Today it belongs to the Coptic Orthodox Church.

The entirety of the Nitrian Desert is sometimes called the Desert of Macarius, for he was the pioneer monk in the region. The ruins of numerous monasteries in this region almost confirm the local tradition that the cloisters of Macarius were equal in number to the days of the year.

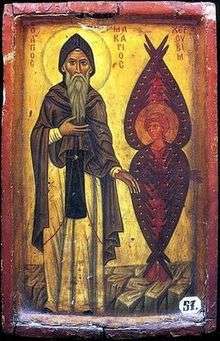

Saint Macarius Depicted on the Camposanto Fresco in Pisa

Saint Macarius the Great, one of the Egyptian desert recluses and a disciple of Saint Anthony the Great, is depicted on the right edge of the Triumph of Death fresco in Pisa. A group of leisurely aristocrats and their animals occupy the central part of the fresco. These rich young men and women riding horses, surrounded by their decorative hunting dogs have gone on a pleasant journey. Suddenly, their path, somewhere deep in the woods, is barred by three open sarcophagi with bodies in different degrees of decomposition. Everybody in the scene, including the men, women and even the animals are horrified by this terrible and palpable presence of death. The unsupportable stench hits their noses. The abhorrent scene dismays them. Only Saint Macarius the Great, made wise and powerful by his faith, stands above them all. The mystic Saint teaches the youngsters a lesson about life and death by reading from the scroll. The Florentine sculptor Benvenuto Cellini was inspired by this depiction of Saint Macarius in his painted portrait.

References[12]

- Harmless, William. Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism, p. 174, (Oxford University Press, 2004)

- "Μνήμη τοῦ ὁσίου πατρός ἠμῶν Μακαρίου τοῦ Αἰγυπτίου τοῦ ἀναχωρητοῦ" [Our father Makarios of Egypt the Anchorite, of blessed memory]. Apostoliki Diakonia: Eorlogio (in Greek). Apostoliki Diakonia (Apostolic Auxiliary) of the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- "دير القديس أنبا مقار الكبير". www.stmacariusmonastery.org. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- "Venerable Macarius the Great of Egypt". oca.org. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- Butler, Alban. (1866). The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints. Dublin. p. 35

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Frances Young, From Nicaea to Chalcedon, (2nd edn, 2010), p116

- Johannes Quasten, Patrology Vol. 3. Utrecht, 1966, 162-164.

- J. Quasten, Patrology Vol. 3, 164-165.

- J. Quasten, Patrology Vol. 3, p. 167

- Kaufman, Paul L. (June 2018). "Did Holiness Begin with John Wesley?". The Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist. Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection. 80 (6): 4–5.

- "Venerable Macarius the Great of Egypt". oca.org. Retrieved 2017-11-26.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Macarius the Great. |

- Monastery of Saint Macarius the Great

- Hermit

- Saints Maximos and Domadious

Further reading

- Maloney, GA, SJ (trans.), 1992, Pseudo-Macarius. The Fifty Spiritual Homilies and the Great Letter, CWS, New York: Paulist Press [English translation]

- Mason, AJ (trans.), 1921, Fifty Spiritual Homilies of St Macarius the Egyptian, London: SPCK [English translation]

- Plested, Marcus, 2004. The Macarian Legacy: The Place of Macarius-Symeon in the Eastern Christian Tradition. Oxford: OUP

External links

- Spiritual Homilies 1-5, 6-11, 12-22

- Macarius the Great Select Resources, Bilingual Anthology

- Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1914: "Macarius the Egyptian"

- Wesley Center Online

- Volume 38, Wesleyan Theological Journal, Academic Article on Macarius of Egypt, pp. 103 – 123

- Greek Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with Analytical Indexes

- Great Macarius work in Greek and English

- Works by or about Macarius of Egypt at Internet Archive

- Works by Macarius of Egypt at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)