Khadi

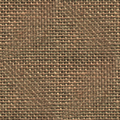

Khadi (IAST: Khādī) is a hand-woven natural fiber cloth originating from eastern regions of the Indian subcontinent, mainly Eastern India, Northeastern India and Bangladesh, but is now broadly used throughout India and Pakistan. [1][2][3]

The cloth is usually woven from cotton however it may also include silk or wool, which are all spun into yarn on a spinning wheel called a charkha. It is a versatile fabric, cool in summer and warm in winter. In order to improve its looks, khādī/khaddar is sometimes starched to give it a stiffer feel. It is widely accepted in various fashion circles.[4] Khadi is being promoted in India by the Khadi and Village Industries Commission and the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

History

Khadi is also known as khaddar. It is usually a rough textured fabric.

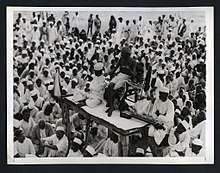

In India, Khadi refers to handwoven and hand spun cloth. Weavers prefer yarn produced by mills because it is more robust and consistent in quality. The Swadeshi movement of boycotting English products during the first two decades of the twentieth Century was popularised by Mahatma Gandhi and Indian mill owners, who, backed by Nationalist politicians, called for a boycott of foreign cloth. Gandhi argued that the mill owners would deny handloom weavers an opportunity to buy yarn because they would prefer to create a monopoly for their own cloth.[5] However, handspun yarn was of expensive and of poor quality. Thus Mahatma Gandhi started spinning himself and encouraging others to do so. He made it obligatory for all members of the Indian National Congress to spin cotton themselves and to pay their dues in yarn. He further made the chakri (spinning wheel) the symbol of the Nationalist movement. Initially the Indian flag was supposed to have a chakri, not the Ashoka Chakra at its centre. Mahatma Gandhi collected large sums of money to create a grass-roots organisation to encourage handloom weaving. This was called the 'khaddar' or 'Khadi' movement.[6]

Under the British Raj Indians were forced to buy expensive clothes, since the British exported the raw materials for cloth to English fabric mills, then re-imported the finished cloth to India.[7][8] The Indian mill owners wanted to monopolise the Indian market themselves. Ever since the American Civil War caused a shortage of American cotton, Britain would buy cotton from India at cheap prices and use the cotton to manufacture cloth. The khadi movement by Gandhi aimed at boycotting foreign cloth.[9] Mahatma Gandhi began promoting the spinning of khadi for rural self-employment and self-reliance (instead of using cloth manufactured industrially in Britain) in the 1920s, thus making khadi an integral part and an icon of the Swadeshi movement.[10][11][12][13][14]

The freedom struggle revolved around the use of khādī fabrics and the dumping of foreign-made clothes. When some people complained about the costliness of khadi to Mahatma Gandhi, he started wearing only dhoti though he used wool shawls when it got cold. Some were able to make a reasonable living by using high quality mill yarn and catering to the luxury market. Mahatma Gandhi tried to put an end to this practice. He even threatened to give up khadi altogether if he didn't get his way. However, since the weavers would have starved if they listened to Gandhi, nothing came of this threat.[10]

India

In 2017, a total of 4,60,000 people were employed in industries making khadi products.[15] Production and sales rose by 31.6% and 33% respectively in 2017 after multi-spindle charkas were introduced to enhance the productivity by replacing the single-spindle charkas.[15] In 2019 it was reported that overall khadi sales in India have risen by 28% in the 5 year period preceding 2018-2019. The revenues from Khadi in the last financial year stood at ₹3,215 crore and the KVIC has set a target of ₹5000 crore to be achieved by 2020.[16] Various states have boards and/or cooperative societies for khadi production, promotion, sale and marketing, such as Haryana Khadi and Village Industries Board, Andhra Pradesh State Handloom Weavers Cooperative Society, Gujarat State Handloom and Handicrafts Development Corporation Ltd, Jharkhand Silk Textile and Handicraft Development Corporation, and Tamil Nadu Handloom Weavers' Cooperative Society. Additionally, several institutes are involved in research and training in this area, such as Indian Institute of Handloom Technology, Indian Institute of Handloom Technology, Champa and Institute of Handloom and Textile Technology.The Handicrafts and Handlooms Export Corporation of India is focused on popularising khadi overseas. The Rehwa Society is an NGO involved in khadi production.

Popular dresses are made using khadi cloth such as dhoti, kurta, and handloom sarees such as Puttapaka Saree, Kotpad Handloom fabrics, Chamba Rumal, Tussar silk etc. Gajam Anjaiah, an Indian master handloom designer and a recipient of the Padma Shri, is known for his innovation and development of tie-dye handloom products along with the Telia Rumal technique of weaving products based on the Ikat process.[17][18]

After Independence, the Government reserved some types of textile production, e.g. towel manufacture for the handloom sector, which resulted in a deskilling of traditional weavers and a boost for the power loom sector. Private Sector enterprises have been able to make handloom weaving somewhat remunerative and the government also continues to promote the use of Khadi through various initiatives.[10][19]

Prime Minister Narendra Modi asserted that khadi cloth is a movement to help the poor.[20] He further highlighted that the Khadi and Village Industries Commission is a statutory organisation engaged in promoting and developing khadi and village industries.[20] He lauded Gujarat and Rajasthan for being well known for khadi poly, while Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir are well known for woolen khadi.[20]

Bangladesh

Khadi, also known as "khaddar" has a long history in Bangladesh. In the 6th century a local variation of Khadi cloth was described by Huen Tsang of China and Marco Polo in the 12th century AD describes a fabric, most probably khadi Muslin in the Bengal region to being as fine as a spider's web.[21]

Romans were great aficionados of Bengal khadi Muslin and imported vast amounts of Khadi. The Khadi weaved by the weavers of Comilla during the Mughal period was renowned as a valuable textile with distinctive characteristics.[22]

During the years of the Indian self-rule movement and later with the independence of Bangladesh, the spirit of khadi was driven with the winds of change. In 1921, Gandhi came to Chandina Upazila in Comilla to inspire local weavers and consequently a branch of 'Nikhil Bharat Tantubai Samity' was established to self-seed and proliferate the sale of goods to other major cities in India.[23]

In the greater Comilla region, weaving centers were developed in Mainamati, Muradnagar, Gauripur and Chandina.

In 1942, political activist Suhasini Das pledged to only wear khadi clothing for the rest of her life.[24]

See also

- Khādī Development and Village Industries Commission (Khadi Gramodyog)

- Khaadi – A Pakistani multinational clothing brand

References

- "The Fascinating History of the Fabric That Became a Symbol of India's Freedom Struggle". The Better India. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-08.

- "Freedom@70: How Khadi is getting a new spin.", Economic Times, 13 August 2017.

- "Clothing Gandhi's Nation: Homespun and Modern India - News - Hamilton College". www.hamilton.edu.

- "Khadi". getcopaycom.ipage.com.

- Sinha, Sangita. "The Story Of Khadi, India's Signature Fabric". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2017-08-08.

- Selin, Helaine (1997). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicines in Non- Western Cultures. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 961. ISBN 978-0792340669.

- https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Pakistan/P8Ee8RaSlUUC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22british+raj%22+selling+clohth+high+cost&pg=PA8&printsec=frontcover

- Mahesh, Aggarwal R. C. /Bhatnagar (July 27, 2005). "Constitutional Development & National Movemen in India". S. Chand Publishing – via Google Books.

- "Historical background of Khadi". www.chandrakantalrks.org. Retrieved 2017-08-08.

- "Saturday Dressing: Kerala govt staff opt for khadi". Business Standard. Press Trust of India. 6 January 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Brown, Theodore M.; Fee, Elizabeth (1 January 2008). "Spinning for India's Independence". American Journal of Public Health. 98 (1): 39. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.120139. PMC 2156064. PMID 18048775.

- Pritchett, Frances. "spinning". www.columbia.edu.

- Cosgrove, Ben. "Gandhi and His Spinning Wheel: The Story Behind an Iconic Photo". Time.

- Cosgrove, Ben. "Gandhi: Quiet Scenes From a Revolutionary Life". Time.

- Jadhav, Radheshyam (11 March 2018). "7 lakh 'lose' jobs in khadi industry, but production goes up by 32%". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Khadi sales zoom 28%, KVIC eyes Rs 5,000 crore in FY20 - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- "Padma awards to Rajesh Khanna, Sharmila Tagore, Rahul Dravid". Tehelka. 25 January 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Padma Awards: List of Awardees". IndiaTimes. Times Internet Limited. 26 January 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Mann Ki Baat: PM Modi urges India to embrace Gandhi's legacy 'Khadi'". Zee News. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "PM Modi in Mann Ki Baat: Khadi not a cloth, but a movement to help the poor". Business Standard. 24 September 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "Cosy Comfort: Khadi". bdnewslive.com. Archived from the original on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- "Khadi Reviving the Heritage". The Daily Star. Dhaka. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- "The story of KHADI". The Daily Star. Dhaka. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- সুহাসিনী দাস [Suhasini Das]. Golden Femina (in Bengali).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khādī. |

- Khadi Culture: Fabrics from the roots of a nation!

- India's Khādī Culture

- Khadi and Village Industries Commission (Govt of India), Official website

- More about Khadi

.svg.png)

'.jpg)