Henry Boyle Townshend Somerville

Vice-Admiral Henry Boyle Townshend Somerville CMG (7 September 1863 – 24 March 1936), generally known as Boyle Somerville, was an Irishman who served in the Royal Navy. He was a maritime author, as well as publishing on ethnography and archaeology. He was shot dead by the IRA.

Biography

Boyle Somerville was born at Castletownshend, Co. Cork. His father was Thomas Henry Somerville and his mother was Adelaide Eliza Coghill[1]. Somerville joined the Royal Navy as a cadet in 1877. His first service was in South America in 1880, and then in the first Egyptian war in 1882. He then spent four years on the China Station.[2] He trained as a Hydrographic Surveyor, and as a Lieutenant worked on the surveys of the Queensland coast and the New Hebrides, now Vanuatu, in the South Pacific, (HMS Dart, 1890-91)[3]. While in Vanuata he carried out ethnographical work, which was published in 1894[4]. In 1893-4 he was surveying in the South Pacific with HMS Penguin. Sounding in the Kermadec Trench between New Zealand and Tonga, they found a depth of 5,155 fathoms (9,427 m), the greatest ocean depth ever found up to that time.[5] They then surveyed New Georgia in the Solomon Islands, also with Penguin, and Somerville published an account of the islands and its peoples[6]. He built a significant collection of ethnographic artefacts from the Solomon Islands which is now in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. In 1895, working on the survey of Tonga, also on Penguin, he took the opportunity to visit Niuafo'ou, and published an early description of the island[7].

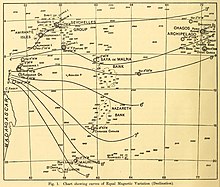

He was promoted to Commander on 31 December 1901,[9] and the following year was posted to the Hydrographic Department for temporary service.[10] He surveyed the Persian Gulf in 1902 (HMS Sphinx)[11][12], and Ceylon and the Indian ocean between 1904 and 1907 with HMS Sealark[1]. In the summer of 1905, Somerville and HMS Sealark were assigned to the Indian Ocean expedition sponsored by the Percy Sladen Trust, which was led by J. Stanley Gardiner. Somerville took part in the scientific work of the expedition, as well as making oceanographic and magnetic observations[13][14][15]. From 1908-1914 he surveyed British coastal waters (1908–14) in HMS Research[1]. He was promoted to Captain in 1912 and Vice Admiral on 1 August 1919. G.S. Ritchie, Hydrographer of the Navy from 1966-71, described him as a "surveyor of distinction"[16]. Shortly before World War I he developed a steam-operated sounding machine for determining ocean depth from a ship that was under way[17][8].

In 1908, while surveying in British waters, he read a book suggesting stone circles and standing stones might have astronomical significance. He thereafter devoted much of his time to surveying such monuments in Britain, Ireland and elsewhere, and became a recognised expert in the field of archaeoastronomy. He contributed papers to the Journal of the British Astronomical Association and Antiquity. His archaeological studies have been reviewed by Lacey (2008)[19]

During World War I he served in the North Atlantic Patrol from 1914-1916, commanding HMS Victorian, HMS Argonaut, HMS Amphitrite and HMS King Alfred. Operations were based around Madeira, the Canary Islands, the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands. With no safe harbours in these islands the ships were always at sea during the night, taking on coal only during daylight hours, to reduce the risk of submarine attacks. This led to one spell of 385 consecutive nights at sea during 1915-1916.[20] In 1917 he was based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, commanding HMS Devonshire on Atlantic convoy support.[1]. One incident he describes from this period was The Great Search of the ship conveying the German Ambassador Count Bernstorff from the USA back to Germany after diplomatic relations were discontinued. This occurred in Halifax, Nova Scotia, took 10 days, and yielded considerable quantities of contraband.[21] As part of the late summer 1917 reorganisation of the burgeoning British Secret Intelligence Service, led by Mansfield Smith-Cumming and his de facto deputy, Colonel Freddie Browning, Somerville was appointed as 'officer in charge of the Naval Section within the Secret Service Bureau.' This was the first career naval officer posting to the Secret Service. In February 1919, Somerville wrote a review setting out a number of basic principles for service and encouraging the development of specialist intelligence technical skills within the navy for intelligence gathering and analysis. Also in February 1919, he was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George "in recognition of valuable services during the war".[22]

He retired on 2 August 1919. After his retirement he returned to the family home at Castletownshend, near Cork in Ireland. During his retirement He continued to work for the Admiralty, in the Hydrographic Department and on the Tidal Committee,[2] and published several books including Ocean Passages for the World in 1923. He also published articles describing his surveying experiences in Blackwood's Magazine. He continued to be active in archaeology, publishing his last paper in 1931[23].

On 24 March 1936 he was killed when four men burst into the house and fired a revolver. IRA chief of staff Tom Barry was involved in the shooting.[24][25] The Vice-Admiral was targeted for allegedly recruiting local men to join the Royal Navy, a claim the family rejected. His family said he did not recruit anyone but merely gave references to young people who called to the family door and asked for a reference. The admiral was Irish language speaker, and he was a supporter of the nationalist Home Rule movement. The men who shot him left a note saying he was shot because he was recruiting for the British Army, and this led to suspicions that the target was in fact his British Army brother that lived close by, and was more prominent and a much more likely target. Somerville's killing was one of the events that led the de Valera government to ban the IRA (18 June 1936)[26]. IRA leader Tom Barry stated in an interview in later years that the shooting was a mistake in that he was only meant to have been taken hostage. [27]

He was the younger brother of the novelist and artist, Edith Somerville, who finished his biography of William Mariner for its posthumous publication.

Published works

- Ocean Passages for the World. Published for Hydrographic Dept., Admiralty, by HMSO (1923). Full text of the second edition (1950) is available at the Internet Archive.

- A series of articles published between 1919 and 1927 in Blackwood's Magazine, including surveying work in Queensland, New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) and New Caledonia and experiences in World War 1:

- "The Great Search". 206 (1249). November 1919: 690–699. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Ninth Cruiser Squadron, Parts I-III". 207 (1251). January 1920: 1–23. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Ninth Cruiser Squadron, Part IV". 207 (1252). February 1920: 153–168. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "A Secret Survey, Part I". 207 (1256). June 1920: 812–825. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "A Secret Survey, Part II". 208 (1257). July 1920: 88–97. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Chart-Makers". 220 (1334). December 1926: 814–851. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Chart-Makers". 221 (1336). February 1927: 243–266. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Chart-Makers". 221 (1338). April 1927: 501–524. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Deepest Depth". 222 (1344). October 1927: 550–565. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

- "The Great Search". 206 (1249). November 1919: 690–699. Cite journal requires

- The Chart-Makers. Blackwell & Sons (1928). A collection of some of the Blackwood's Magazine articles listed above.

- Commodore Anson's Voyage into the South Seas and Around the World. Heinemann. (1934)

- Will Mariner. Faber & Faber. (1936)

- Records of the Somerville Family of Castlehaven & Drishane from 1174 to 1940 (with Edith Anna Somerville). Published by Guy & Co, Cork, 1940

See also:

- The Selected letters of Somerville and Ross edited by Gifford Lewis, Faber (1989)

- Blood-Dark Track: A Family History, by Joseph O'Neill, Granta (2001) for a detailed account of Boyle Somerville's killing.

- MI6 The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949, by Keith Jeffery, Bloomsbury (2010).

References

- Long, Patrick. "Somerville, Henry Boyle Townshend". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Vice-Admiral Henry Boyle Townshend Somerville, C.M.G.". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 7 (1): 149–150. 1937. JSTOR 25513871.

- Somerville, Boyle (1928). The Chart Makers. Edinburgh: Blackwood.

- Somerville, Boyle T. (1894). "Notes on Some Islands of the New Hebrides". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 23: 2–21. JSTOR 2842310.

- Somerville, Boyle (October 1927). "The Deepest Depth". Blackwood's Magazine. 222 (1344): 550–565.

- Somerville, Boyle T. (1897). "Ethnographical Notes in New Georgia, Solomon Islands". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 26: 357–412. JSTOR 2842009.

- Somerville, Boyle T (1896). "Account of a Visit to Niuafou, South Pacific". The Geographical Journal. 7 (1): 65–71. JSTOR 1773680.

- Admiralty Manual of Hydrographic Surveying, Revised Edition. Hydrographic Department of the Admiralty. 1948. p. 213.

- "No. 27393". The London Gazette. 3 January 1902. p. 3.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times (36922). London. 11 November 1902. p. 5.

- Somerville, Boyle (June 1920). "A Secret Survey, Part I". Blackwood's Magazine. 207 (1256): 812–825.

- Somerville, Boyle (1920). "A Secret Survey, Part II". Blackwood's Magazine. 208 (1257): 88–97.

- Gardiner, J.Stanley; Cooper, C.Forster (1907). "The Percy Sladen Trust expedition to the Indian Ocean in 1905, under the leadership of Mr. J. Stanley Gardiner. No. I. Description of the expedition". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London.2nd Series: Zoology. 12 (1): 1–56. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1907.tb00507.x.

- Gardiner, J.Stanley; Cooper, C.Forster (1907). "No. IX. Description of the expedition (continued from p.55)". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London.2nd Series: Zoology. 12 (1): 111–175. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1907.tb00074.x.

- Gardiner, J.Stanley; Somerville, Boyle T.; Fryer, J.C.F. (1910). "The Percy Sladen Trust expedition to the Indian Ocean in 1905 under the leadership of Mr. J. Stanley Gardiner, Volume III. No. I Description of the expedition (concluded) with observations for terrestrial magnetism and some account of Bird and Dennis Islands". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London.2nd Series: Zoology. 14 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1910.tb00520.x.

- Ritchie, G.S. (1967). The Admiralty Chart. London: Hollis & Carter. p. 365.

- Ritchie, Steve (G.S.) (2005). "Three hydrographic quantum leaps". The International Hydrographic Review. 6 (2): 6–8.

- Somerville, Boyle (1912). "Prehistoric Monuments in the Outer Hebrides, and Their Astronomical Significance". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 42: 23–52.

- Lacey, Brian (2008). "The Irish archaeological studies of Boyle Somerville, 1909-1936". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 138: 147–158. JSTOR 27920493.

- Somerville, Boyle (February 1920). "The Ninth Cruiser Squadron, Part IV". Blackwood's Magazine. 207 (1252): 153–168.

- Somerville, Boyle (November 1919). "The Great Search". Blackwood's Magazine. 206 (1249): 690–699.

- "No. 13403". The Edinburgh Gazette. 14 February 1919. p. 908.

- Somerville, Boyle (1931). ""The Fort" on Knock Drum, West Carbery, County Cork". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Seventh Series, Vol. 1 (1): 1–14. JSTOR 25513581.

- "Vice-Admiral Shot Dead Outrage In County Cork". The Times. 25 March 1936.

- Hart, Peter (January 2008) [2004]. "Barry, Thomas Bernardine (1897–1980)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/65835. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Coogan, Tim Pat (1993). Eamon de Valera: the man who was Ireland. New York: Harper Perennial. pp. 480–481. ISBN 0-06-017121-9.

- O'Neill, Joseph (10 February 2001). "Shaking the family tree". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Boyle Townshend Somerville. |

- Finlay, Finola. "Boyle Somerville: Ireland's First Archaeoastronomer". Roaringwater Journal. Retrieved 20 July 2020.