Henri Huet

Henri Huet (4 April 1927 – 10 February 1971) was a French war photographer, noted for his work covering the Vietnam War for Associated Press (AP).

Henri Huet | |

|---|---|

Henri Huet | |

| Born | Henri Huet April 4, 1927 Da Lat, Vietnam |

| Died | February 10, 1971 (aged 43) Savannakhet Province, Laos |

| Occupation | Combat photographer |

Early life

Henri Huet was born in Da Lat, Vietnam, the son of a Breton engineer and Vietnamese mother. He went to France as a boy of five, was educated at Saint-Malo in Brittany, and studied at the art school in Rennes and began his adult career as a painter. He later joined the French Navy and received training in photography, returning to Vietnam in 1949 as a combat photographer in the First Indochina War. After discharge from the navy when the war ended in 1954, Huet remained in Vietnam as a civilian photographer working for the French and American governments. While employed by the United States Operation Mission (USOM) photo lab (1955–1960), he enjoyed the mentorship of lab director, Charles E. (Gene) Thomas, who himself had been a combat photographer in WWII. Several of Huet's photos reflect the influence of Thomas's work. He went on to work for United Press International (UPI), later transferring to AP in 1965, covering the Vietnam War.

Photographic career

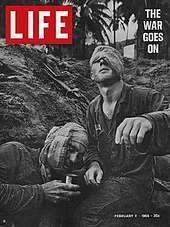

Huet's photographs of the war were influential in moulding American public opinion. One of his most memorable series of photographs featured Pfc Thomas Cole, a young medic of the First Cavalry division, tending fellow soldiers despite his own wounds. The series of twelve photographs was published in the 11 February, 1966 edition of LIFE magazine, with one of the haunting images featuring on the cover. In 1967 the Overseas Press Club awarded Huet the Robert Capa Gold Medal for the "best published photographic reporting from abroad, requiring exceptional courage and enterprise".[1]

Death

On February 10, 1971, during South Vietnam's invasion of southern Laos, known as Operation Lam Son 719, Huet and three other photojournalists, joined the operation commander, Lt Gen Hoàng Xuân Lãm, on a helicopter inspection tour of the battlefront. The pilots of the Republic of Vietnam Air Force (RVNAF) UH-1 Huey carrying the photojournalists lost their way and flew into the most heavily defended area of the Ho Chi Minh trail, where it and a second chopper were shot down by hidden North Vietnamese 37mm anti-aircraft guns, killing all 11 on the photographers' aircraft and four on the other. Huet was 43.

Huet's fellow photographers were Larry Burrows, British, of LIFE magazine, Kent Potter, American, of UPI and Keizaburo Shimamoto, a Japanese freelance photographer working for Newsweek. The crash site was rediscovered in 1996 and in March, 1998, a second search team from the US Joint Task Force Full Accounting (JTFFA), the Pentagon unit responsible for recovering MIA remains in Indochina and elsewhere, excavated the mountainside, finding aircraft parts, camera pieces, 35mm film, along with traces of human remains, which proved too scant for laboratory identification.[2]

On April 3, 2008, a ceremony was held at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. to mark the interment of the remains of Huet, Burrows, Potter and Shimamoto, along with the seven South Vietnamese also killed in the shootdown. Speakers included Richard Pyle, Saigon bureau chief of The Associated Press in Saigon at the time of the crash, and Horst Faas, former AP Saigon photo chief, who were co-authors of Lost Over Laos: A True Story of Tragedy, Mystery, and Friendship, published by Da Capo Press in 2003 and re-released in paperback in 2004. The book recounts the personal stories of the four photographers, the events leading to their deaths, and how Pyle helped the Hawaii-based MIA unit locate the long-lost Laotian crash site in 1996. Pyle and Faas were present when site 2062 was excavated in March 1998. In late 2002, the search unit, renamed the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), declared the case closed on grounds of circumstantial group identification. After bureaucratic complications blocked efforts to bury the group remains on official ground, the Newseum agreed to accept them and arranged in 2006 for their acquisition from JPAC. The ceremony on April 3, 2008, which preceded the Newseum's own official opening by a week, was attended by more than 100 guests including relatives of Huet, Burrows and Potter, and many former Vietnam War colleagues. Speakers in addition to Pyle and Faas included Newseum president Peter Prichard and AP president Tom Curley, and Burrows' son Russell spoke for the families.

A second book about Huet, titled Henri Huet: J'etais photographe de guerre au Vietnam, was published in Paris in 2006, authored by Helene Gedouin, a senior editor at Hachette Livre publishers of Paris, and Faas, with contributions from Pyle and other former Vietnam colleagues. The story of the shootdown also was told in Requiem, by the Photographers who died in Vietnam and Indochina, edited by Faas and Tim Page, and published by Random House, New York, in 1997.

Among his colleagues covering the war, Huet was respected for his dedication, bravery and skill in the field, and known for his sense of humor and kindness. Dirck Halstead, the Photo Chief of United Press International in 1965, remarked that he "always had a smile on his face".[3]

1971 British Obituary

Tribute to Huet by Ramsay Wood, Photo News Weekly — Feb 24, 1971

The death of Larry Burrows in a helicopter crash in Laos was extensively reported in the British Press – quite naturally so, for he was a native Londoner. But three other combat photographers were presumably killed in that same misadventure. One of them was Henri Huet, 43 star Associated Press photographer in Vietnam, and – like Burrows – a Robert Capa award winner for still photography “requiring exceptional courage and enterprise”.

Born in Dalat, South Vietnam of a French father and Vietnamese mother, Henri Huet had perhaps more photographic experience of warfare in Vietnam than any other professional. Starting as a French Navy cameraman in 1949, he covered the earlier French war in Indochina until 1952 and then worked for various American governmental agencies before joining AP in 1963.

Being half Vietnamese, his personal perception of Vietnam's tragedy probably went deeper than the majority of the Western press corps. There was something distinctly Oriental in Huet's modest manner: in a profession where bragadaccio is more the norm, he stood out – possibly even more than Burrows – because of his quietness. Huet was short in body, but giant hearted with friendliness, and amazingly efficient as a photographer. One had the impression of a nimble and spritely little man – an Ariel with a couple of Nikons around his neck. There was a quality of invisibility about him which no doubt helped him snatch so many remarkable candid shots of the war. But there was also an aura of sadness about Huet; he was the father of two children, and no doubt the divorce from his Vietnamese wife had left behind painful scars in so sensitive a nature.

Combat photography, as he explained it, seemed to provide that degree of intensity in living which some people find so acutely missing in ordinary civilian existence. Like the moth circling the flame, however, the state of mind engendered by repeatedly surviving danger becomes its own opiate. A good combat photographer becomes, to a certain extent, hooked on risking his life, and thus subject to the deadly probability that the more he succeeds the less chance he has of staying alive. When I last met Huet in 1969 he agreed to being interviewed.

“The only thing special about combat photography,” he said, “is the state of mind of the photographer. You’ve got to have this feeling of not caring what happens to you. It’s kind of a gamble you make with yourself based on the fact that you’ve got nothing to lose. This nothing means people for me: no family, children, wife – nobody who I feel responsible to. If you’ve got that kind of background, then it is a great adventure. Yes, I would even consider it a kind of fun. There you are pushing the shutter button in an exciting situation: things are happening all around you and it’s very hard not to get a good photograph. You just point the camera and shoot. After a while it’s just like anything else, and you don’t think about it.”

I first met Huet in the summer of 1959 when I was 15. He was then working for the American Information Services in Vietnam and all of his pictures were comparatively peaceful in subject matter: calendars with pretty Vietnamese girls; typical farmyard animals and agricultural produce; construction workers on the girders of a new bridge; the odd politician at a village meeting. These images projected by the American Economic Mission were of a gentle Asian country benefitting from US Foreign Aid.

I was obsessed with photography at the time, and for two summers tagged along as Huet's unofficial apprentice which, I think, was somewhat to his embarrassment as he did not purport to be a teacher. He was extremely easy-going and kind, never overtly putting forward any fixed photographic lesson, yet always willing to answer questions. What he did provide was a first taste of the professional's world. I think that psychologists call it ‘learning by contact’. What evolved from our summers’ companionship was, for me, more a sense of friendship than of schooling.

Just before the Vietcong terrorists began demolishing the carefully cultivated image of peacefulness and burgeoning democracy, I left Vietnam. It was nine years before I had the chance to meet Huet again. We went to his small bedsitter where he showed me the cover and 10-page spread in Life which won him the Robert Capa award in 1967. He also had an especially gruesome collection of photographs showing the war injuries sustained by other, less lucky photographers. There is one of these I will never forget, and which will probably keep me away from combat photography forever: a picture of a young man whose right arm in an instant been shorn off at the shoulder by a Vietcong rocket, his undamaged camera drooping mid-air on a neckstrap in horror and shock. But somehow often to his own surprise, Huet had always managed to stay together.

“Once the VC attacked the airbase at Da Nang and I happened to get inside before the gates were closed for security. All the other Press photographers had been at a party, and by the time they got there everything was locked up tight. They waited at the gates for four hours before they were allowed in. It’s primitive competition stuff like this – between friends – that really makes the adrenalin go. The VC were sending mortars right into the parked American planes and choppers. The explosions were huge and beautiful. While the mortar attack is going on the VC send in their sappers who lay charges to every second or third plane – poof, lying on a runaway shooting all this stuff and really enjoying it because I’ve got colour film in my cameras. Suddenly this American Air Force captain comes screaming by in a jeep, hits the brakes, jumps out and comes running over to me. ‘What the hell do you think you’re doing?’ he yells. ‘Oh, I’m a photographer,’ I say, ‘I’m taking pictures.’ He looks at me like I'm crazy, runs back to his jeep and takes off fast.

“Another time I was on a plane with a mortar crew from a big unit that was moving out. The plane was stuffed full with mortars and ammunition and the men who were responsible for this artillery. Just before we took off someone asked me if I would get on another plane as they were worried about the weight. ‘Sure, why not,’ I said. It didn't make any difference to me. So later we land at our destination and a pilot comes up and asks if I heard about this mortar plane, wasn't I on it just before take-off? ‘Well you sure are lucky,’ he says, ‘It crashed just after it cleared the runway, and everybody aboard was killed! When you have things like that happen to you fairly often, you begin to get a tingle inside you that really makes you wonder.”

In retrospect, our last conversation over a lunch in Saigon almost two years ago has its own haunting quality that makes me wonder too. Huet told me how his leg had been badly wounded in 1967 and about the Belgian woman he met and came to love during his convalescence. Things had now changed for him, and going into action – now that he had something to lose – had become more like a nightmare.

“It took me six months to recover and now all I can think about is my fiancée. Before, I used to be keen to get to the worst fighting; I’d jump in a chopper and only feel alive when we got to the action. Now all I do is worry about getting out, and that’s bad. Recently I was with a unit in the Delta and we were pinned down by heavy enemy fire. Our radio was out and we were cut off from the main group of the operations. Usually what you do when you are pinned down like this is call in the planes or the artillery until the VC withdraw, but this time we were on our own and had to fight our way out. I was lying in the mud, and I was thinking of my life and my beautiful girl friend back in New York and how much I would miss if I was killed now and I was just moaning to myself ‘merde merde merde’ over and over again. I didn't take any pictures at all but just kept down, and now I knew I couldn't do this kind of work well anymore. I was too scared. And I was scared because I had something to lose. But this sergeant gets up and yells, ‘Assault!’ and most of us get up and run. We don't know were we’re going because we’ve lost radio contact with the main group, but we’re lucky and hook up in a couple of hundred yards. A colonel pal looks at me and says he didn't think he'd see me again because another unit was also cut off from radio contact and they found them all dead. So you can see now why I cannot wait to go to Tokyo. I have lost my daredevil spirit.”

I have learned that Huet did get to Tokyo soon after I last saw him, and stayed out of the war for several months – even managing a holiday to Indonesia with his love. But something must have persuaded him to return, for he soon asked AP for reassignment to Saigon. Somehow I sense a whiff of desperate unhappiness in this decision – maybe things did not work out as he expected in Tokyo? I don't know what happened, if anything, to make him change his mind. All I know is that he did, and now his dead body probably lies tangled in a crush of metal and jungle somewhere near the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos. His friends and professional associates lie nearby: Burrows, Kent Potter and Keisaburo Shimamoto.

Work

Huet's photograph of Thomas Cole featured on the cover of LIFE magazine

Huet's photograph of Thomas Cole featured on the cover of LIFE magazine Huet's poignant photograph of colleague Dickey Chapelle receiving last rites after being fatally wounded by a booby trap in Vietnam.

Huet's poignant photograph of colleague Dickey Chapelle receiving last rites after being fatally wounded by a booby trap in Vietnam.

Notes

- "The Robert Capa Gold Medal". OPC Awards. Overseas Press Club of America. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-11-05. Retrieved 2006-06-04.

- Pyle, Richard (March 22, 1998). "Laos 1971 Crash Scene Searched". Associated press. Retrieved 2006-06-04.

- Halstead, Dirck (November 1997). "Requiem". Digital Journalist. Retrieved 2006-06-04.

References

- "Requiem - Portrait Of Henri Huet". Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- "Henri Huet, The forgotten Photographer". Archived from the original on 2007-08-12. Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- Raphaël Millet, catalogue of the exhibition Requiem, Singapore, Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), in partnership with Month of Photography Asia, July 2011, pp. 4–5. Remembering Henri Huet, the Young Veteran. ISBN 978-981-08-9097-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)