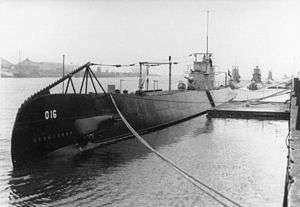

HNLMS O 16

HNLMS O 16 was a unique submarine of the Royal Netherlands Navy that saw service during World War II. The design came from G. de Rooij and had a diving depth of 80 metres (260 ft).[1] She was the first submarine of the Royal Netherlands Navy manufactured from high quality Steel 52. Also riveting was reduced 49% and replaced by welding when compared to preceding ships.[2]

O 16 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | O 16 |

| Operator: |

|

| Builder: | Koninklijke Maatschappij De Schelde |

| Laid down: | 28 December 1933 |

| Launched: | 27 January 1936 |

| Commissioned: | 16 October 1936 |

| Homeport: |

|

| Identification: | 16 |

| Fate: | Sunk by mine on 15 December 1941 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Unique submarine |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 76.53 m (251 ft 1 in) |

| Beam: | 6.55 m (21 ft 6 in) |

| Draught: | 3.97 m (13 ft 0 in) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: |

|

| Range: | |

| Test depth: | 80 m (262 ft) |

| Complement: | 36–42 |

| Armament: |

|

Design

HNLMS O 16 was designed by chief engineer of the Royal Netherlands Navy, G. de Rooij.[3] It was the first submarine he designed as chief engineer of the Royal Netherlands Navy, the previous submarines where designed by his predecessor, J.J. van der Struyff. When compared to other submarines designed at the time, the design of O 16 can be called 'unique'. The main cause for this were the high requirements set by the Royal Netherlands Navy, which aimed at increasing the weight of the submarine while retaining a high speed.[4] This resulted in a submarine that was 4 metres (13 ft) longer than K XVII and weighed 130 tons more than K XVII. However, even though O 16 was 20 percent larger than K XVII, O 16 was still faster than the previous submarine.[5] De Rooij thanked this increase in speed and weight to his design, which was based on research done in Wageningen. The design included a different shape of the hull, the forward torpedo tubes were set more apart from each other, and the hull was designed from high quality steel (German steel 'St52').[5] The different shape of the hull lead to an increase in speed, while putting the forward tubes more apart from each other would result in less chances of torpedoes hitting each other. Furthermore, the use of high quality steel for the hull led to more tensile strength, elasticity and mechanical properties. The inside of O 16 was also different from previous submarines of the Royal Netherlands Navy. For example, it had a refrigerator and multiple sinks for the crew. The design of O 16 was such a success that the Polish Navy ordered four submarines based on this design. This resulted in the Polish submarines ORP Orzeł and ORP Sęp.[6]

Ship history

Commissioning and shake down cruise

O 16 was laid down on 28 December 1933 at the Koninklijke Maatschappij De Schelde, Vlissingen and launched on 27 January 1936. On 16 October 1936 she was commissioned in the Royal Netherlands Navy.[7] At the time of its commissioning it was the largest submarine in the Royal Netherlands Navy.[5] Her shake down cruise took place from 11 January till 6 April 1937.[8] During the shake down cruise the submarine was under command of LTZ1 C.J.W. van Waning. The trip was marked by the bad weather and uneasy sea, which led to an annoying situation for the crew. Many became seasick and could not do their duty, while preparing food was hard. The shake down trip took O 16 to the port of Hamilton, Bermuda (5 February 1937), Norfolk, Virginia (13–14 February 1937), and Washington, D.C. (15–24 February). During their time in Washington, Commander van Waning and one of the guests aboard the submarine, Prof.dr.ir. F.A. Vening Meinesz, were granted audience with American President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[9] After the trip to Washington, O 16 resumed its journey to Ponta Delgada (7–8 March 1937) and Lisbon (12 March 1937). The Spanish Civil War was taking place during this time, which had as effect that General Francisco Franco blocked access of ships to the Mediterranean Sea with the aid of the Royal Italian Navy.[10] The Dutch government therefore ordered O 16 to escort ships and perform convoy duties, she performed these together with other ships of the Royal Netherlands Navy.[11][12] For example, on 18 March 1937 O 16 performed convoy duties together with HNLMS Hertog Hendrik. Finally, on 1 April 1937 O 16 went home to the Netherlands to finish her shake down cruise, she arrived at the Dutch port of Den Helder on 16 April 1937.[13]

Between 16 April 1937 and 12 December 1938 O 16 took part in multiple events and helped the Royal Netherlands Navy with torpedo developments.[14] Some notable events O 16 took part in include a fleet demonstration off the coast of Scheveningen on 3 September 1938. This demonstration took place to celebrate Queen Wilhelmina being queen and head of state of the Netherlands for 40 years.[15] After these events, O 16 was taken out of service between 12 December 1938 and halfway April 1939 for her two yearly maintenance. The maintenance happened at the Rijkswerf te Willemsoord in Den Helder.[16]

Sent to the Dutch East Indies

In 1939 O 16 was sent to the Dutch East Indies via the Suez Canal and attached to the submarine division there.[3] This made the O 16 the first O series submarine that went to the Dutch East Indies, normally only K series submarines were sent to the Dutch colony in Southeast Asia.[16] During her journey to the Dutch East Indies, she came across and docked at several ports, such as Lisbon, Port Said and Aden. O 16 finally reached her destination, Tanjung Priok, on 5 June 1939. Soon after the Netherlands surrendered to Germany in 1940, the situation in Southeast Asia also degraded. A Japanese attack was expected, while there were also rumors of German raiders who had their eyes on the Dutch East Indies. To this end O 16 among other ships was sent on patrol around the Dutch East Indies to catch these German raiders. For example, in September 1940 O 16 together with K XVIII were sent from Tanjung Priok to shadow the steamship Lematang and tanker Olivia, during their trip from Durban to Lourenço Marques, with the intention to sink any possible German raider.[17] Besides these missions O 16 could mostly be found docked in the port of Soerabaja. The reason for this was that the Royal Netherlands Navy, United States Navy, Royal Australian Navy and the British Royal Navy were still in talks about how their possible cooperation or alliance against Japan would take form (such as deciding who commands what ships). Only in November did the Dutch government-in-exile in London decide that submarine division I, to which O 16 belonged, would come under British command.[18]

World War II

After being put under British command O 16 was sent on multiple patrol missions. This started in November 1941 when she was sent on patrol in the South China Sea. Her home-port also changed to Singapore as a result.[3] On 6 December 1941 O 16 was sent for patrol to the Gulf of Siam. During this patrol O 16 spotted two Japanese destroyers, however, since there was no war with Japan no torpedoes were launched.[19] This situation changed a day later, on 7 December 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. This resulted in war with the Japanese, while the Dutch government also decided to put two more submarine divisions under British command, which meant that three of the four Dutch submarine divisions were now under British command (Submarine division I, to which O 16 belonged, was already under British command).[20] In the night of 8 to 9 December 1941 O 16 spotted two Japanese destroyers which were searching for something, but did not pursue them.[21] On 9 December 1941 at 9 pm O 16 received a message from British command to sail for, with other submarines in submarine division I and II, the coast of Siam.[22] The reason for this was that a large number of Japanese troop transports were spotted off the coast. The following day, on 11 December at 6 am, the submarines were ordered to set course to the coast of Malacca and Siam, between Kota Bharu and Singora.[6] Japanese troopships were spotted there and the submarines were meant to take them out. Earlier that night, however, O 16 had spotted a Japanese troopship and launched three torpedoes, but because of the bad weather the crew could not confirm if they had hit and sunk the ship.[21] The next day, on 12 December 1941, O 16 once again spotted a Japanese troopship heading towards Pattani, Anton Bussemaker, commander of O 16, gave the order to follow the ship.[21] Eventually the Japanese troopship decided to dock at Bay of Soengei Patani, this happened around 9:30 pm. While LTZ2 H.J.J. van Eynsbergen maneuvered O 16 into the bay, the crew discovered that more Japanese troopships were docked besides the one they had followed.[19] The bay was only 11 metres (36 ft) deep so diving was impossible, instead O 16 approached the docked Japanese troopships on her electric motors and prepared her torpedoes. If she was to be discovered, the likelihood of escaping was low, the troopships were equipped with guns that were used to protect against ships and surfaced submarines.[23] When the commander deemed O 16 close enough, four torpedoes were launched simultaneously at four different troopships.[20] When the four torpedoes hit their targets and exploded, two more torpedoes were launched, the result was that the four Japanese troopships were sunk.[24] However, some ships did not fully sink and another was only slightly damaged.[25] Nonetheless, the crew of O 16 were immensely happy about their achievement and retreated to their home-port Singapore with only having one torpedo left.

Missing and found

On 15 December 1941 during her homebound voyage to Singapore O 16 hit a Japanese naval mine near Tioman Island, while leaving the Gulf of Siam.[11] Only one man out of the crew of 42 survived.[26] The survivor, quartermaster Cor de Wolf, managed to swim to Dayang Island and eventually get in contact with the Royal Netherlands Navy, which brought him to Singapore.[6] There he briefed Dutch navy officers what had happened to the O 16. According to Cor de Wolf he was on the bridge when he heard a loud noise and saw the submarine break into two parts.[27] The submarine started sinking within a minute and before he knew it he was adrift in the water. While drifting around in the sea he started screaming for others and eventually saw some crew members also drifting around, to which he swam.[27] When he reached them, he noticed that the other crew members which had survived were those that were alongside him on the bridge when the submarine hit a mine, except for Commander Bussemaker. These were First Lieutenant Jeekel, Corporal Bos, Lance corporal van Tol, Marine 1st Class Kruijdenhof. They all start screaming for Commander Bussemaker, which replied to them, but he was too far away to be reached, and relatively soon was not heard or seen again.[28] The 5 survivors meanwhile tried orientating where they were and came to the conclusion that they had to swim in the direction between the left side of the moon and the right side of a star that were in sky.[29] Shortly after the sun started rising above the South China Sea Lance corporal van Tol did not have the strength anymore to swim further and sank away. Meanwhile, Islands started to appear on the horizon, to which the remaining survivors started swimming. However, around 8 am First Lieutenant Jeekel could not go on and sank away. Shortly after, Cor de Wolf asked the other two remaining surviros, Marine 1st Class Kruijdenhof and Corporal Bos, how they holding were holding up. The only answer he heard from both was "thirsty". Nonetheless, after 6 and a half hours of swimming, Marine 1st Class Kruijdenhof sank slowly away into the sea around 9 am.[30] At the same time the current started to get stronger in the ocean and pushed Cor de Wolf and Corporal Bos to the east of the Islands they saw in the distance.[31] After the sun started to go under and both had swam for 17 hours, Corporal Bos told Cor de Wolf he had no strength left to swim and started sinking away.[29] Before he sank, he also told Cor de Wolf to send his regards to his wife and children if he managed to survive. The loss of Corporal Bos meant that Cor de Wolf was all alone in his struggle to reach land. It eventually took him 35 hours till he made it to Dayang Island.[32] There he came across a native who could not understand him, however, he did take him to his village head which spoke a language Cor de Wolf also knew, namely Malay. Through the village head he managed to make contact with first Australian units and eventually the Royal Netherlands Navy.[33]

The wreck of the O 16 was not found until 1995, when a Swedish diver, named Sten Sjostrand, came across a wreck of a submarine.[29] He did not know with certainty to which navy the submarine belonged to, but had a feeling that it could be the missing O 16. To be certain he called the Dutch newspaper AD, which connected in turn brought him into contact with the Royal Netherlands Navy.[34] They confirmed to Sten Sjostrand that it is a big certainty that the submarine he found was the O 16. An expedition was organized which included people from the navy, two newspapers and two descendants of Commander Bussemaker.[29][23] They met with Sten Sjostrand on 24 Oktober 1995 in Tioman to visit the wreck and to confirm if it really was the O 16.[35] On 26 October 1995 at 4 AM the expedition team, Sten Sjostrand and 4 other divers went on the boat Cadenza to the location of the wreck, which was located 22 miles northeast of Tioman and on a diving depth of 53 meters.[36] At the location of the wreck the divers started diving to look if they could see name of the O 16 on the hull. However, after several dives they could not find any name on the wreck, instead they started recording during their dive sessions. Later they compared what they recorded with the designs of the O 16 and could confirm that the wreck was indeed the O 16.[23]

In October 2013, a crane vessel was photographed dredging up the wreck of O 16 for sale as scrap metal.[37]

Summary of raiding history

Ships sunk and damaged by O 16.[25]

| Date | Ship name | Nationality/Type | Tonnage (GRT) | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 December 1941 | Ayatosan Maru/Sakura Maru | Japanese troopship | 9,788/7,170 | Damaged |

| 12 December 1941 | Tosan Maru | Japanese troopship | 8,666 | Sunk (later salvaged) |

| 12 December 1941 | Asosan Maru | Japanese troopship | 8,812 | Sunk (later salvaged) |

| 12 December 1941 | Kinka Maru | Japanese troopship | 9,306 | Sunk (later salvaged) |

| 12 December 1941 | Ayatosan Maru | Japanese troopship | 9,788 | Damaged |

Footnotes

- van Royen, p. 17

- van Royen, p. 19

- Kimenai, Peter (28 March 2014). "Nederlandse Onderzeeboten van het type O 16". www.go2war2.nl. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- Tom Womack, The Allied Defense of the Malay Barrier, 1941–1942 (2016) p. 49.

- Gerretse and Wijn, p.9

- van Royen, p. 18

- de Bles, Boven and Homburg; inside of the book cover

- van Royen, p. 22

- van Royen, pp. 23

- Beevor, p. 199.

- Mark, 83

- 100 jaar onderzeeboten (PDF), Koninklijke Marine, 9 May 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2018, retrieved 30 January 2018

- van Royen, p. 24

- van Royen, pp. 24–25

- Jaarboek KM, p. 129

- van Royen, p. 25

- "Boat O 16". www.dutchsubmarines.nl. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Bezemer, 166-170

- Benighof, Mike (May 2017). "The Dutch Submarine Flotilla, 1941-42". www.avalanchepress.com. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- de Bles, Boven and Homburg, pp. 99

- van Royen, p. 30

- van Royen, p. 29

- Waarheid O 16 boven water, 18 October 2016, retrieved 2 February 2018

- Captain John F. O'Connell, USN (RET.), Submarine Operational Effectiveness in the 20th Century: Part Two (1939 - 1945) (2011) p.89

- Boat O 16, dutchsubmarines.nl, retrieved 6 February 2018

- Willigenburg, 64

- Beers, 21

- van Royen, pp. 35

- Karremann, Het vergaan van de O 16 en verhaal van de enige overlevende.

- Ibidem.

- van Royen, pp. 39

- Vermiste onderzeeboot komt weer, ,boven water, digibron.nl, 22 April 1982, retrieved 25 June 2018

- van Royen, pp. 38

- van Royen, pp. 52

- van Royen, pp. 53

- van Royen, pp. 55

- HMAS Perth: WWII warship grave stripped by salvagers, ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), 13 Dec 2013, retrieved 16 Dec 2013

See also

References

- Beevor, Antony (2001) [1982]. The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-14-100148-7.

- de Bles, Harry; Boven, Graddy; Homburg, Leon (2006). Onderzeeboten!. Zaltbommel/Den Helder: Aprilis/Marinemuseum. ISBN 978-9059941304.

- Jalhay, P.C.; Wijn, J.J.A. (1997). Ik nader ongezien! De onderzeeboten van de Koninklijke Marine. Amsterdam: De Bataafsche Leeuw. ISBN 978-9067074629.

- Ministerie van Defensie, Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Marine (KM) 1937-1938, ('s-Gravenhage, 1939).

- van Royen, P.C. (1997). Hr.Ms. K XVII en Hr.Ms. O 16: De ondergang van twee Nederlandse onderzeeboten in de Zuid-Chinese Zee (1941). Amsterdam: Van Soeren. ISBN 978-90-6881-075-2.

- Mark, Chris (1997). Schepen van de Koninklijke Marine in W.O. II. Alkmaar: De Alk b.v. ISBN 9789060135228.

- Karremann, Jaime (4 May 2015). "Het vergaan van de O 16 en verhaal van de enige overlevende". marineschepen.nl. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Gerretse, K.H.L.; Wijn, J.J.A. (1993). Drie-cylinders duiken dieper: de onderzeeboten van de dolfijn-klasse van de Koninklijke Marine. Amsterdam: Van Soeren. ISBN 978-9068810271.

- Willigenburg, Henk van (2010). Nederlandse Oorlogsschepen 1940-1945. Emmen: Lanastra.

- Beers, A.C. (1945). Periscoop op! De oorlogsgeschiedenis van den Onderzeedienst der Koninklijke Marine. London.

- Bezemer, K.W.L. (1987). Zij vochten op de zeven zeeën. Houten. ISBN 9789026920455.