Fringe theories about the Shroud of Turin

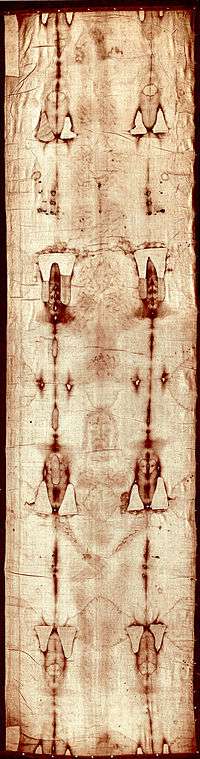

The Shroud of Turin is a length of linen cloth bearing the imprint of the image of a man, and is believed by some to be the burial shroud of Jesus. Despite conclusive scientific evidence that it is of medieval origin, multiple alternative theories about the origin of the shroud dating it to the time of Christ have been proposed.

Although three radiocarbon dating tests performed in 1988 provided conclusive evidence of a date of 1260 to 1390 for the shroud, some researchers have challenged the dating based on various theories, including the provenance of the samples used for testing, biological or chemical contamination, incorrect assessment of carbon dating data, as well as other theories. However, the alternative theories challenging the radiocarbon dating have been disproved by scientists using actual shroud material, and are thus considered to be fringe theories.

The Holy See received custody of the shroud in 1983, and as with other relics, makes no claims about its authenticity. After the 1988 round of tests, no further dating tests have been allowed.

Overview

The Shroud of Turin is a length of linen cloth bearing the negative image of a man who is alleged to be Jesus of Nazareth. The cloth itself is believed by some to be the burial shroud he was wrapped in when he was buried after his crucifixion. The origins of the shroud and its images are the subject of multiple fringe theories. Diverse arguments have been made in various publications claiming to prove that the cloth is the authentic burial shroud of Jesus, based on disciplines ranging from chemistry to biology and medical forensics to optical image analysis.

In 1988, three radiocarbon dating tests dated a sample of the shroud as being from the Middle Ages,[1] between the years 1260 and 1390. Some shroud researchers have challenged this dating, arguing in favor of fringe theories.[2][3][4][5][6][7] However, all of the scientific hypotheses used to challenge the radiocarbon dating have been scientifically refuted,[8][9][10] including the medieval repair hypothesis,[11][12][13][14] the bio-contamination hypothesis[15][16] and the carbon monoxide hypothesis.[9] As the highly-respected[17] journal Nature put it, writing about the radiocarbon dating: "These tests provide conclusive evidence that the linen of the Shroud of Turin is mediaeval."[18]

Defective sample theories

Allegations have been made that the sample of the shroud chosen for testing was defective in some way, usually involving questions about the provenance of the threads: for example that the sample chosen was not from the original shroud but from a repair or restoration carried out in the Middle Ages.

Medieval repair argument

Although the quality of the radiocarbon testing itself is unquestioned, criticisms have been raised regarding the choice of the sample taken for testing, with suggestions that the sample may represent a medieval repair fragment rather than the image-bearing cloth.[19][20][21][22] It is hypothesised that the sampled area was a medieval repair which was conducted by "invisible reweaving". Since the C14 dating at least four articles have been published in scholarly sources contending that the samples used for the dating test may not have been representative of the whole shroud.[23][22][24]

Questionable provenance of samples

The medieval repair argument was included in an article by American chemist Raymond Rogers, who conducted chemical analysis for the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) and who was involved in work with the Shroud since the STURP project began in 1978. Rogers took 32 documented adhesive-tape samples from all areas of the shroud and associated textiles during the STURP process in 1978.[23] He received 14 yarn segments from Luigi Gonella (Department of Physics, Polytechnic University of Turin) on 14 October 1979, which Gonella told him were from the Raes sample. On 12 December 2003, Rogers received a tiny fragment of what he was told was a shroud warp thread, and a tiny fragment of what he was told was a shroud weft thread, which Luigi Gonella told him had been taken from the radiocarbon sample before it was distributed for dating. The actual provenance of these threads is uncertain, as Gonella was not authorized to take or retain genuine shroud material,[14] but Gonella told Rogers that he excised the threads from the center of the radiocarbon sample.[23]

Raymond Rogers stated in a 2005 article that he performed chemical analyses on these undocumented threads, and compared them to the undocumented Raes threads as well as the samples he had kept from his STURP work. He stated that his analysis showed: "The radiocarbon sample contains both a gum/dye/mordant coating and cotton fibers. The main part of the shroud does not contain these materials."[23] He speculated that these products may have been used by medieval weavers to match the colour of the original weave when performing repairs and backing the shroud for additional protection. Based on this comparison Rogers concluded that the undocumented threads received from Gonella did not match the main body of the shroud, and that in his opinion: "The worst possible sample for carbon dating was taken."[25]

In March 2013, Giulio Fanti, professor of mechanical and thermal measurement at the University of Padua conducted a battery of experiments on various threads that he believes were cut from the shroud during the 1988 carbon-14 dating, and concluded that they dated from 300 BC to 400 AD, potentially placing the Shroud within the lifetime of Jesus of Nazareth.[26] Because of the manner in which Fanti obtained the shroud fibers, many are dubious about his findings. The shroud’s official custodian, Archbishop Cesare Nosiglia of Turin, told Vatican Insider: "As there is no degree of safety on the authenticity of the materials on which these experiments were carried out [on] the shroud cloth, the shroud's custodians cannot recognize any serious value to the results of these alleged experiments."[27][28] Barrie Schwortz, a member of the original STURP investigation team, commented on Fanti’s theory: "But it would be more convincing if the basic research had first been presented in a professional, peer-reviewed journal. If you’re using old techniques in new ways, then you need to submit your approach to other scientists."[27]

Response to restoration claims

The official report of the dating process, written by the people who performed the sampling, states that the sample "came from a single site on the main body of the shroud away from any patches or charred areas."[18]

As part of the testing process in 1988, a Derbyshire laboratory in the UK assisted the University of Oxford radiocarbon acceleration unit by identifying foreign material removed from the samples before they were processed.[29] Edward Thomas Hall of the Oxford team noticed two or three "minute" fibers which looked "out of place",[29] and those "minute" fibers were identified as cotton by Peter South (textile expert of the Derbyshire laboratory) who said: "It may have been used for repairs at some time in the past, or simply became bound in when the linen fabric was woven. It may not have taken us long to identify the strange material, but it was unique amongst the many and varied jobs we undertake." [29]

Mechthild Flury-Lemberg is an expert in the restoration of textiles, who headed the restoration and conservation of the Turin Shroud in 2002. She has rejected the theory of the "invisible reweaving", pointing out that it would be technically impossible to perform such a repair without leaving traces, and that she found no such traces in her study of the shroud.[30][31]

H. E. Gove, former professor emeritus of physics at the University of Rochester and former director of the Nuclear Structure Research Laboratory at the University of Rochester, helped to invent radiocarbon dating and was closely involved in setting up the shroud dating project. He also attended the actual dating process at the University of Arizona. Gove has written (in the respected scientific journal Radiocarbon) that: "Another argument has been made that the part of the shroud from which the sample was cut had possibly become worn and threadbare from countless handlings and had been subjected to medieval textile restoration. If so, the restoration would have had to be done with such incredible virtuosity as to render it microscopically indistinguishable from the real thing. Even modern so-called invisible weaving can readily be detected under a microscope, so this possibility seems unlikely. It seems very convincing that what was measured in the laboratories was genuine cloth from the shroud after it had been subjected to rigorous cleaning procedures. Probably no sample for carbon dating has ever been subjected to such scrupulously careful examination and treatment, nor perhaps ever will again."[15]

In 2010, statisticians Marco Riani and Anthony C. Atkinson wrote in a scientific paper that the statistical analysis of the raw dates obtained from the three laboratories for the radiocarbon test suggests the presence of contamination in some of the samples. They conclude that: "The effect is not large over the sampled region; … our estimate of the change is about two centuries."[32]

In December 2010, Timothy Jull, a member of the original 1988 radiocarbon-dating team and editor of the peer-reviewed journal Radiocarbon, coauthored an article in that journal with Rachel A Freer-Waters. They examined a portion of the radiocarbon sample that was left over from the section used by the University of Arizona in 1988 for the carbon dating exercise, and were assisted by the director of the Gloria F Ross Center for Tapestry Studies. They viewed the fragment using a low magnification (~30×) stereo microscope, as well as under high magnification (320×) viewed through both transmitted light and polarized light, and then with epifluorescence microscopy. They found "only low levels of contamination by a few cotton fibers" and no evidence that the samples actually used for measurements in the C14 dating processes were dyed, treated, or otherwise manipulated. They concluded that the radiocarbon dating had been performed on a sample of the original shroud material.[33]

Vanillin loss theory

Raymond Rogers[23] argued in the scientific journal Thermochimica Acta that the presence of vanillin differed markedly between the unprovenanced threads he was looking at, which contained 37% of the original vanillin, while the body of the shroud contained 0% of the original vanillin. He stated that: "The fact that vanillin cannot be detected in the lignin on shroud fibers, Dead Sea Scrolls linen, and other very old linens indicate that the shroud is quite old. A determination of the kinetics of vanillin loss suggest the shroud is between 1300 and 3000 years old. Even allowing for errors in the measurements and assumptions about storage conditions, the cloth is unlikely to be as young as 840 years".[23]

It has been stated that Rogers’ vanillin-dating process is untested, and the validity thereof is suspect, as the deterioration of vanillin is heavily influenced by the temperature of its environment – heat strips away vanillin rapidly, and the shroud has been subjected to temperatures high enough to melt silver and scorch the cloth.[14] In a 2020 paper, respected pro-authenticity advocates Bryan Walsh and Larry Schwalbe stated of this test that "Rogers’ method has limitations and his results have not yet been widely accepted."[34] Rogers' analysis is also questioned by skeptics such as Joe Nickell, who reasons that the conclusions of the author, Raymond Rogers, result from "starting with the desired conclusion and working backward to the evidence".[35]

Contamination theories

Various theories call into question results of carbon-14 dating, based on contamination by bacteria, reactive carbon, or carbon monoxide.

By bacteria

Pictorial evidence dating from c. 1690 and 1842 indicates that the corner used for the dating and several similar evenly spaced areas along one edge of the cloth were handled each time the cloth was displayed, the traditional method being for it to be held suspended by a row of five bishops. Others contend that repeated handling of this kind greatly increased the likelihood of contamination by bacteria and bacterial residue compared to the newly discovered archaeological specimens for which carbon-14 dating was developed. Bacteria and associated residue (bacteria by-products and dead bacteria) carry additional carbon-14 that would skew the radiocarbon date toward the present.

Rodger Sparks, a radiocarbon expert from New Zealand, had countered that an error of thirteen centuries stemming from bacterial contamination in the Middle Ages would have required a layer approximately doubling the sample weight.[36] Because such material could be easily detected, fibers from the shroud were examined at the National Science Foundation Mass Spectrometry Center of Excellence at the University of Nebraska. Pyrolysis-mass-spectrometry examination failed to detect any form of bioplastic polymer on fibers from either non-image or image areas of the shroud. Additionally, laser-microprobe Raman analysis at Instruments SA, Inc. in Metuchen, New Jersey, also failed to detect any bioplastic polymer on shroud fibers.

Harry Gove, director of Rochester's laboratory (one of the laboratories not selected to conduct the testing), once hypothesised that a "bioplastic" bacterial contamination, which was unknown during the 1988 testing, could have rendered the tests inaccurate. He has, however, also acknowledged that the samples had been carefully cleaned with strong chemicals before testing.[37] He noted that different cleaning procedures were employed by and within the three laboratories, and that even if some slight contamination remained, about two thirds of the sample would need to consist of modern material to swing the result away from a 1st century date to a Medieval date. He inspected the Arizona sample material before it was cleaned, and determined that no such gross amount of contamination was present even before the cleaning commenced.[15]

By reactive carbon

Others have suggested that the silver of the molten reliquary and the water used to douse the flames may have catalysed the airborne carbon into the cloth.[38]

Kouznetsov claims

The Russian Dmitri Kouznetsov, an archaeological biologist and chemist, claimed in 1994 to have managed to experimentally reproduce this purported enrichment of the cloth in ancient weaves, and published numerous articles on the subject between 1994 and 1996.[39]

Kouznetsov's results could not be replicated, and no actual experiments have been able to validate this theory, so far.[40]

Jull, Donahue and Damon of the NSF Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometer Facility at the University of Arizona attempted to replicate the Kouznetsov experiment, and could find no evidence for the gross changes in age proposed by Kouznetsov et al. They concluded that the proposed carbon-enriching heat treatments were not capable of producing the claimed changes in the measured radiocarbon age of the linen, that the attacks by Kouznetsov et al. on the 1988 radiocarbon dating of the shroud "in general are unsubstantiated and incorrect," and that the "other aspects of the experiment are unverifiable and irreproducible."[41][42]

Scientific refutation

Gian Marco Rinaldi and others proved that Kouznetsov never performed the experiments described in his papers, citing non-existent fonts and sources, including the museums from which he claimed to have obtained the samples of ancient weaves on which he performed the experiments.[43][44][45][46]

Fraud and arrest

Kouznetsov was arrested in 1997 on American soil under allegations of accepting bribes by magazine editors to produce manufactured evidence and false reports.[47]

By carbon monoxide in smoke

In 2008, John Jackson of the Turin Shroud Center of Colorado proposed a new hypothesis – namely the possibility of more recent enrichment if carbon monoxide were to slowly interact with a fabric so as to deposit its enriched carbon into the fabric, interpenetrating into the fibrils that make up the cloth. Jackson proposed to test if this were actually possible.[48] Christopher Ramsey, the director of the Oxford University Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, took the theory seriously and agreed to collaborate with Jackson in testing a series of linen samples that could determine if the case for the Shroud's authenticity should be re-opened. Before conducting the tests, he told the BBC that "With the radiocarbon measurements and with all of the other evidence which we have about the Shroud, there does seem to be a conflict in the interpretation of the different evidence."[49] Ramsey stressed that he would be surprised if the results of the 1988 tests were shown to be far out – especially "a thousand years wrong" – but he insisted that he was keeping an open mind.[50]

The results of the tests were to form part of a documentary on the Turin Shroud which was to be broadcast on BBC2. The producer of the 2008 documentary, David Rolfe, suggested that the quantity of carbon 14 found on the weave may have been significantly affected by the weather, the conservation methods employed throughout the centuries,[51] as well as the volatile carbon generated by the fire that damaged the shroud while in Savoy custody at Chambéry. Other similar theories include that candle smoke (rich in carbon dioxide) and the volatile carbon molecules produced during the two fires may have altered the carbon content of the cloth, rendering carbon-dating unreliable as a dating tool.[52][53]

In March 2008, Ramsey reported back on the testing that: "So far the linen samples have been subjected to normal conditions (but with very high concentrations of carbon monoxide). These initial tests show no significant reaction – even though the sensitivity of the measurements is sufficient to detect contamination that would offset the age by less than a single year. This is to be expected and essentially confirms why this sort of contamination has not been considered a serious issue before." He noted that carbon monoxide does not undergo significant reactions with linen which could result in an incorporation of a significant number of CO molecules into the cellulose structure. He also added that there is as yet no direct evidence to suggest the original radiocarbon dates are not accurate.[48]

In 2011, Ramsey commented that in general "there are various hypotheses as to why the dates might not be correct, but none of them stack up."[54]

Incorrect dating calculation theory

In 1994, J. A. Christen applied a strong statistical test to the radiocarbon data and concluded that the given age for the shroud is, from a statistical point of view, correct.[55]

However critics claim to have identified statistical errors in the conclusions published in Nature:[18] including: the actual standard deviation for the Tucson study was 17 years, not 31, as published; the chi-square distribution value is 8.6 rather than 6.4, and the relative significance level (which measures the reliability of the results) is close to 1% – rather than the published 5%, which is the minimum acceptable threshold.[56][57]

In a 2020 paper, respected pro-authenticity advocates Bryan Walsh and Larry Schwalbe stated in the Discussion section as follows:[58]

- "At this time, the source of the statistical heterogeneity of the Shroud data is unknown, but one of two broad hypotheses could reasonably account for the effect. One is that some differences may have existed in either the sample processing or measurement protocols of the different laboratories. The other is that some inherent variation was present in the carbon isotopic composition of the Shroud sample itself ...

- "An alternate hypothesis is that some difference in residual contamination may have occurred as a result of differences in the individual laboratories’ cleaning procedures …

- "In support of the contamination hypothesis, Fig. 4 illustrates how the mean results from the Zurich and Tucson data (open symbols) agree within their calculated experimental error (note level B-B′), whereas that from Oxford does not (A-A′). If the Zurich and Tucson data were displaced upward by 88 RCY as shown in the figure all of the results would agree within the uncertainty observed. Indeed, if the magnitude of the “adjustment” were as small as ~10 RCY, the χ2 analysis would confirm a statistical homogeneity assuming the uncertainties in the data did not change."

Other theories

Other theories have been proposed as well, such as the nuclear emissions theory which claims that the image was formed from nuclear emissions from an earthquake that struck Jerusalem in 33 A.D.[59]

See also

References

- Taylor, R.E. and Bar-Yosef, Ofer. Radiocarbon Dating, Second Edition: An Archaeological Perspective. Left Coast Press, 2014, p. 165

- Barcaccia, Gianni; Galla, Giulio; Achilli, Alessandro; Olivieri, Anna; Torroni, Antonio (5 October 2015). "Uncovering the sources of DNA found on the Turin Shroud". Scientific Reports. 5: 14484. Bibcode:2015NatSR...514484B. doi:10.1038/srep14484. PMC 4593049. PMID 26434580.

- Riani, M.; et al. (2013). "Regression analysis with partially labelled regressors: carbon dating of the shroud of Turin". Statistics and Computing. 23 (4): 551–561. doi:10.1007/s11222-012-9329-5.

- Poulle, Emmanuel (December 2009). "Les sources de l'histoire du linceul de Turin. Revue critique". Revue d'Histoire Ecclésiastique. 104 (3–4): 747–782. doi:10.1484/J.RHE.3.215.

- Rogers, Raymond N. (20 January 2005). "Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of turin" (PDF). Thermochimica Acta. 425 (1–2): 189–194. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2004.09.029. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Marino, Joe (2000). "Evidence for the Skewing of the C-14 Dating of the Shroud of Turin Due to Repairs" (PDF).

- Benford, Sue (2002). "Textile Evidence Supports Skewed Radiocarbon Date of Shroud of Turin" (PDF).

- Chivers, Tom (20 December 2011). "The Turin Shroud is fake. Get over it". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- Christopher Ramsey, Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, March 2008, http://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/shroud.html

- Radiocarbon Dating, Second Edition: An Archaeological Perspective, By R.E. Taylor, Ofer Bar-Yosef, Routledge 2016; pg 167-168

- Flury-Lemburg, Mechthild. "The Invisible Mending of the Shroud, the Theory and the Reality" (PDF). Shroud.com. Shroud of Turin Education and Research Association. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Jackson, John P. (5 May 2008). "A New Radiocarbon Hypothesis" (PDF). Turin Shroud Center of Colorado. Retrieved 18 February 2014 – via Shroud.com.

- R.A. Freer-Waters, A.J.T. Jull, Investigating a Dated piece of the Shroud of Turin, Radiocarbon, 52, 2010, pp. 1521–1527.

- Schafersman, Steven D. (14 March 2005). "A Skeptical Response to Studies on the Radiocarbon Sample from the Shroud of Turin by Raymond N. Rogers". llanoestacado.org. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- Gove, H. E. (1990). "Dating the Turin Shroud: An Assessment". Radiocarbon. 32 (1): 87–92. doi:10.1017/S0033822200039990.

- "Debate of Roger Sparks and William Meacham on alt.turin-shroud". Shroud.com. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Fersht, Alan (28 April 2009). "The most influential journals: Impact Factor and Eigenfactor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (17): 6883–6884. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.6883F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903307106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2678438. PMID 19380731.

- Damon, P. E.; Donahue, D. J.; Gore, B. H.; Hatheway, A. L.; Jull, A. J. T.; Linick, T. W.; Sercel, P. J.; Toolin, L. J.; Bronk, C. R.; Hall, E. T.; Hedges, R. E. M.; Housley, R.; Law, I. A.; Perry, C.; Bonani, G.; Trumbore, S.; Woelfli, W.; Ambers, J. C.; Bowman, S. G. E.; Leese, M. N.; Tite, M. S. (1989). "Radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin". Nature. 337 (6208): 611–5. Bibcode:1989Natur.337..611D. doi:10.1038/337611a0.

- Busson, Pierre (1991). "Sampling error?". Nature. 352 (6332): 187. Bibcode:1991Natur.352..187B. doi:10.1038/352187d0.

- John L. Brown, "Microscopical Investigation of Selected Raes Threads From the Shroud of Turin"Article (2005)

- Robert Villarreal, "Analytical Results On Thread Samples Taken From The Raes Sampling Area (Corner) Of The Shroud Cloth" Abstract (2008)

- Benford, M. Sue; Marino, Joseph G. (2008). "Discrepancies in the radiocarbon dating area of the Turin Shroud". Chemistry Today. 26 (4): 4–12. INIST:20575837.

- Rogers, Raymond N. (2005). "Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of turin". Thermochimica Acta. 425 (1–2): 189–194. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2004.09.029.

- Emmanuel Poulle, ″Les sources de l'histoire du linceul de Turin. Revue critique″, Revue d'Histoire Ecclésiastique, 2009/3-4, Abstract Archived 2011-07-10 at the Wayback Machine; G. Fanti, F. Crosilla, M. Riani, A.C. Atkinson, "A Robust statistical analysis of the 1988 Turin Shroud radiocarbon analysis", Proceedings of the IWSAI, ENEA, 2010.

- Turin Shroud 'could be genuine as carbon-dating was flawed Stephen Adams in the Daily Telegraph 10 Apr 2009

- "In March 2013 Giulio Fanti... concluded that [threads from the shroud] dated from 300 BC to 400 AD":

- Bennettsmith, Meredith (28 March 2013). "Shroud Of Turin Real? New Research Dates Relic To 1st Century, Time Of Jesus Christ". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Doug Stanglin (30 March 2013). "New test dates Shroud of Turin to era of Christ". Usatoday.com. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- "New testing dates Shroud of Turin to era of Christ". Pcusa.org. 10 April 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- "New research suggests Shroud of Turin dates to Jesus' era". Fox News. 29 March 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Personal Post (1 April 2013). "New testing dates Shroud of Turin to era of Christ". Washington Post. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Central New York (29 March 2013). "Shroud of Turin may date back to biblical times, new research indicates". syracuse.com. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Science Shines New Light on Shroud of Turin’s Age; BY SHAFER PARKER JR. National Catholic Register; 05/06/2013 at http://www.ncregister.com/daily-news/science-shines-new-light-on-shroud-of-turins-age/

- Shroud of Turin returns to spotlight with new pope, new app, new debate; NBC News, Friday Mar 29, 2013, at http://cosmiclog.nbcnews.com/_news/2013/03/29/17517272-shroud-of-turin-returns-to-spotlight-with-new-pope-new-app-new-debate

- Rogue fibres found in the Shroud Textile Horizons, December 1988

- The Shroud, by Ian Wilson; Random House, 2010, pgs 130-131

- The Invisible Mending of the Shroud, the Theory and the Reality; by Mechthild Flury-Lemberg, at http://www.shroud.com/pdfs/n65part5.pdf

- Riani M., Atkinson A.C., Fanti G., Crosilla F., (4 May 2010). "Carbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin: Partially Labelled Regressor and the Design of Experiments". The London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- Freer-Waters, Rachel A; Timothy Jull, A J (2016). "Investigating a Dated Piece of the Shroud of Turin". Radiocarbon. 52 (4): 1521. doi:10.1017/S0033822200056277.

- An instructive inter-laboratory comparison: The 1988 radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin", by Bryan Walsh & Larry Schwalbe, published in 2020 in the Journal of Archaeological Science (Reports Volume 29, February 2020, 102015), freely available here

- Joe Nickell. "Claims of Invalid "Shroud" Radiocarbon Date Cut from Whole Cloth". Skeptical Inquirer. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- "Debate of Roger Sparks and William Meacham on alt.turin-shroud". Shroud.com. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Meacham, William (1 March 1986). "From the Proceedings of the Symposium "Turin Shroud - Image of Christ?"". Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- Moroni, M. & van Haelst, R. – ‘'Natural Factors Affecting the Apparent Radiocarbon Age of Textiles’’. Shroud News, Issue No. 100, February 1997

- "Kouznetsov published numerous articles on the subject between 1994 and 1996:"

- Kouznetsov, D. A.; Ivanov, A. A.; Veletsky, P. R. (1996). "A Re-evaluation of the Radiocarbon Date of the Shroud of Turin Based on Biofractionation of Carbon Isotopes and a Fire-Simulating Model". Archaeological Chemistry. ACS Symposium Series. 625. pp. 229–47. doi:10.1021/bk-1996-0625.ch018. ISBN 978-0-8412-3395-9.

- Kouznetsov D. A.; Ivanov A. A.; Veletsky P. R.; Charsky V. L.; Beklemishe O. S. (1995). "A laboratory model for studies on the environment-dependent chemical modifications in textile cellulose". New J. Chem. 19: 1105–09. INIST:10874688.

- Kouznetsov D. A.; Ivanov A. A.; Veletsky P.R. (1996). "Effects of fires and biofractionation of carbon isotopes on results of radiocarbon dating of old textiles: the Shroud of Turin". Journal of Archaeological Science. 23: 23–34. doi:10.1006/jasc.1996.0009.

- Kouznetsov, Dmitri A.; Ivanov, Andrey A.; Veletsky, Pavel R. (1994). "Detection of alkylated cellulose derivatives in several archaeological linen textile samples by capillary electrophoresis/mass spectrometry". Analytical Chemistry. 66 (23): 4359. doi:10.1021/ac00095a037.

- Kouznetsov, Dmitri; Ivanov, Andrey; Veletsky, Pavel (1996). "Analysis of Cellulose Chemical Modification: A Potentially Promising Technique for Characterizing Cellulose Archaeological Textiles". Journal of Archaeological Science. 23: 23–34. doi:10.1006/jasc.1996.0003.

- Fesenko, A. V. – Belyakov, A. V. – Til’kunov, Y. N. – Moskvina, T. P. – On the dating of the Shroud of Turin – Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Vol. 71, No. 5, 2001, pp. 528-531

- Jull, A.J.T.; Donahue, D.J.; Damon, P.E. (1996). "Factors Affecting the Apparent Radiocarbon Age of Textiles: A Comment on "Effects of Fires and Biofractionation of Carbon Isotopes on Results of Radiocarbon Dating of Old Textiles: The Shroud of Turin", by D. A. Kouznetsovet al". Journal of Archaeological Science. 23: 157–160. doi:10.1006/jasc.1996.0013.

- An Archaeological Perspective, By R.E. Taylor, Ofer Bar-Yosef, Colin Renfrew, pg 167, at https://books.google.com/books?id=w6-oBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA164&dq=gove,+shroud+of+turin&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjwvePsiLXPAhVpJsAKHeDCBM4Q6AEIRTAD#v=onepage&q=shroud&f=false

- M. Polidoro. Notes on a Strange World: The Case of the Holy Fraudster. Skeptical Inquirer, Volume 28, Number 2, March/April 2004.

- v2.0 ©2006 Laurence A. Moran. "Laurence Moran. Dmitri Kouznetsov is No Scientist". Bioinfo.med.utoronto.ca. Archived from the original on 1 November 2006. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Richard Trott (2 May 2004). "Dmitri Kouznetsov's Mystery Citations". Talkorigins.org. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Kouznetsov, Dmitri; Ivanov, Andrey; Veletsky, Pavel (1996). "Effects of fires and biofractionation of carbon isotopes on results of radiocarbon dating of old textiles: The Shroud of Turin". Journal of Archaeological Science. 23: 109–121. doi:10.1006/jasc.1996.0009.

- Kouznetsov, D.A. - La datazione radiocarbonica della Sindone di Torino: quanto fu accurata e quanto potrebbe essere accurata? - Atti del Convegno di San Felice Circeo (LT), 24-25 Agosto 1996, pp. 13-18.

- Kouznetsov, D. A.; Ivanov, A. A.; Veletsky, P. R.; Charsky, V. L.; Beklemishev, O. S. (1996). "A Laboratory Model for Studying Environmentally Dependent Chemical Modifications in Textile Cellulose". Textile Research Journal. 66 (2): 111. doi:10.1177/004051759606600208.

- Meacham, W. (2007). The amazing Dr Kouznetsov. ANTIQUITY-OXFORD- 81, 779

- Ramsey, Christopher (22 March 2008). "ORAU - Shroud of Turin". C14.arch.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- Omaar, Rageh (21 March 2008). "Science/Nature | Shroud mystery 'refuses to go away'". BBC News. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Fresh tests on Shroud of Turin; By Jonathan Petre; Religion Correspondent; The Telegraph; 25 Feb 2008 at - https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1579810/Fresh-tests-on-Shroud-of-Turin.html

- Chickos, J.S., and Uang, J. (2001). Chemical Modification of Cellulose. The Possible Effects of Chemical Cleaning on Fatty Acids Incorporated in Old Textiles (St. Louis MO, Department of Chemistry - University of Missouri-St. Louis).

- Brunati, E. - Note critiche sulla datazione della S.Sindone con il radiocarbonio - Typescript, Gennaio 1994, pp. 1-45.

- Cardamone-Blacksburg, J. - La cellulosa dal lino; caratterizzazione e datazione - Typescript, Symposium Scientifique International de Paris sur le Linceul de Turin, 7-8 Septembre 1989, pp. 1-5.

- The Turin Shroud is fake. Get over it Tom Chivers in the Daily Telegraph 20 Dec 2011

- Christen, J. Andres (1994). "Summarizing a Set of Radiocarbon Determinations: A Robust Approach". Applied Statistics. 43 (3): 489–503. doi:10.2307/2986273. JSTOR 2986273.

- Fanti, G., and Marinelli, E. (1998a). Results of a Probabilistic Model Applied to the Research carried out on the Turin Shroud.

- Fanti, G., and Marinelli, E. (1998b). Risultati di un modello probabilistico applicato alle ricerche eseguite sulla Sindone di Torino.

- An instructive inter-laboratory comparison: The 1988 radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin", by Bryan Walsh & Larry Schwalbe, published in 2020 in the Journal of Archaeological Science (Reports Volume 29, February 2020, 102015), freely available here

- Wilensky-Lanford, Brook (26 February 2014). "Latest Shroud of Turin Theory: Nuclear Emissions". Religion Dispatches. Retrieved 17 October 2018.