Fort Snelling

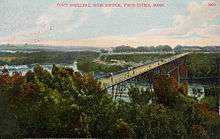

Fort Snelling, replaced Fort Saint Anthony,once it was completed at the same location in the Northwest Territory. It is a former United States Army fortification located on the bluff overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers. The Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, a National Park Service unit, includes historic Fort Snelling.

Fort Snelling | |

Fort Snelling's round tower | |

| |

| Location | Fort Snelling Unorganized Territory, Minnesota, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Just south of Minneapolis and across the Mississippi River from St. Paul and the Minnesota River from Mendota Heights. |

| Coordinates | 44°53′34″N 93°10′50″W |

| Built | 1819 |

| Architect | Colonel Josiah Snelling |

| Website | http://www.historicfortsnelling.org |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000401 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 15 October 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | 19 December 1960[2] |

It is located within Fort Snelling Unorganized Territory that is bordered by Hennepin, Ramsey and Dakota Counties. The Minnesota Historical Society administers the historic Fort. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources administers Fort Snelling State Park at the bottom of the bluff. Fort Snelling once encompassed the Park's land. It has been designated as a National Historic Landmark and cited as a "National Treasure" by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[3]

History

Origins

In 1805, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike acquired Pike's Purchase from the Sioux Nation for the United States, comprising 100,000 acres (400 km²) of land in the area. Significant European-American settlement began in the late 1810s. Following the War of 1812, the United States Department of War built a chain of forts and installed Indian agents at them between Lake Michigan and the Missouri River. These forts primarily protected the northwestern territories from Canadian and British encroachment. The Army founded Fort Saint Anthony in 1819.

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Leavenworth commanded the 5th Infantry Regiment (United States) that constructed the original Fort Saint Anthony from 1820 to 1824. During that time Colonel Josiah Snelling took command of the outpost. The initial camp had been along the Minnesota river. However, it was moved and during construction of the stone fort. During that period most of the soldiers lived at Camp Coldwater which was by a spring. It was the source of drinking water to the fort throughout the 19th century. The spring held a special significance to the Sioux that lived in Minnesota. The post surgeon began recording meteorological observations at Fort Saint Anthony in January 1820, beginning one of the longest near-continuous weather records in the country. Upon completion in 1825, the Army renamed the fort Fort Snelling in honor of its commander and architect.

Frontier post

The Army at the northwestern frontier outposts tried: to restrict commercial use of the rivers to United States citizens (after the War of 1812 the US banned British-Canadian traders from operating in the US), keep Indian lands free of white settlement until permitted by treaties, enforce law and order, and protect legitimate travelers and traders. At Fort Snelling, the garrison also attempted to keep the peace among the Dakota people.[4]

Colonel Snelling suffered from chronic dysentery, and bouts of the illness made him susceptible to anger. Recalled to Washington, he left Fort Snelling in September 1827. Colonel Snelling died in summer 1828 from complications due to dysentery and a "brain fever".

John Marsh, a native of Danvers, Massachusetts, came to the fort during the early 1820s. There, he set up the first school in the Northwest Territory, for the children of the officers. He developed a good relationship with the local Dakota people. He compiled a dictionary for the Dakota language. He had studied medicine at Harvard for two years before leaving without earning a degree. He continued his medical studies under the tutelage of the Fort's physician, Dr. Purcell. The physician died before Marsh completed the two-year course, so he still had no medical degree.[5] Marsh eventually went west to California.

In 1830 Fort Snelling was the birthplace of John Taylor Wood. He served on the Merrimack at the Battle of Hampton Roads during the civil war.[6]

Career army officer and artist Lieutenant Colonel Seth Eastman did two tours at Fort Snelling. He commanded the fort during the second in the 1840s.[7][8] He completed many paintings and drawings of the Dakota while there, recording their customs and lives.[9] He was commissioned by Congress to illustrate the six-volume study of Indian Tribes of the United States by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, which was published 1851-1857 with hundreds of his works.[10]

As the towns of Minneapolis and St. Paul grew and with Minnesota Statehood before congress, the need for a forward frontier military post had ceased. In 1857, with the Fort's deactivation looming, the garrison was sent to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to join the other units being sent to Utah for what became known as the Utah War. With the departure of the 10th Infantry, Fort Snelling was designated surplus government property. In 1858, when Minnesota became a state, the Army sold it to Franklin Steele, a friend of the sitting President, James Buchanan,[11] for $90,000. At that time the Fort sat on 8000 acres (32 km²). A portion of that land was later annexed into south Minneapolis.)[12] The balance of that original land is now Fort Snelling State Park(2,931 acres), Fort Snelling National Cemetery(436 acres), Fort Snelling VA Hospital(160 acres), Minnesota Veterans Home(53 acres), the Upper Post Veterans Home, Minneapolis St Paul International Airport and the Minneapolis-St Paul Joint Air Reserve Station(are 2,930 acres).

Slavery at the Fort

When Fort Snelling was built in 1820, fur traders and officers at the post, including Colonel Snelling, used slave labor for cooking, cleaning, and other domestic chores. Although slavery was a violation of both the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the Missouri Compromise of 1820, an estimated 15 - 30 enslaved Africans worked at the Fort.[13] US Army officers submitted pay vouchers and to cover the expenses of retaining enslaved workers. From 1855 - 1857, nine individuals were enslaved at Fort Snelling. The last slave-holding unit, the 10th Infantry Regiment (United States), was transferred to Utah in 1857. Slavery was constitutionally outlawed when Minnesota became a state in 1858. [14]

Two enslaved women that had lived at the Fort sued for their freedom and were set free in 1836. One, named Rachel, was a slaved to a Lieutenant Thomas Stockton at Fort Snelling from 1830 - 1831, then at Fort Crawford at Prairie du Chien until 1834. When Rachel and her son were sold in St. Louis, she sued claiming that she had been illegally enslaved in the Minnesota Territory. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled in her favor in 1836 and she was freed. At this ruling, another enslaved woman named Courtney and her son William, who were sold by a fur trader named Alexis Bailly in St. Louis in 1834, were also freed.[14]

Army Surgeon Dr. John Emerson purchased the slave Dred Scott in Saint Louis, Missouri, a slave state. He was stationed at Fort Snelling during much of the 1830s, having brought Dred and his wife Harriet with him. Dred and Harriet were slaves at Fort Snelling from 1836 - 1840. Dr. Emerson's wife, Irene returned to St. Louis taking the Scotts and their children in 1840. In 1843 Dred sued for his family's freedom for illegally being indentured in free territory. Although he lost that first trial, he appealed and in 1850 his family was given their freedom. In 1852, Emerson appealed and the Scotts were again enslaved. Dred Scott appealed that decision and in 1857 the US Supreme Court decided that the Scotts would stay enslaved. Dred Scott v. Sandford was a landmark case that held that neither enslaved nor free Africans were meant to hold the privileges or constitutional rights of United Stated Citizens. This case garnered national attention and pushed political tensions towards the Civil War. [14][13]

A longstanding precedent in freedom suits of "once free, always free" was overturned in this case. (The cases were combined under Dred Scott's name.) It was appealed to the United States Supreme court. In Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), Chief Justice Taney ruled that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional and that Africans had no standing under the constitution, so could not sue for freedom. The decision increased sectional tensions between the North and South.

Civil War and afterwards

During the American Civil War, Franklin Steele leased Fort Snelling back to the War Department for use as an induction station. When Governor Ramsey offered President Lincoln 1000 troops to fight the South the volunteers he got were organized at Fort Snelling into a Regiment, the 1st Minnesota. More than 24,000 recruits were trained there.[15]

Minnesota units mustered in at Fort Snelling:

- 1st Minnesota April 1861

- 2nd Minnesota June-July 1861

- 3rd Minnesota Oct-Nov 1861

- 4th Minnesota Oct-Nov 1861

- 5th Minnesota Mar-Apr 1862

- 6th Minnesota Sep-Nov 1862

- 7th Minnesota Aug-Oct 1862

- 8th Minnesota Jun-Sep 1862

- 9th Minnesota Aug-Oct 1862

- 10th Minnesota Aug-Nov 1862

- 11th Minnesota Aug-Sep 1864

- 1st Minnesota Infantry Battalion Aug-Sep 1864

- 1st Minnesota Sharpshooters Company Apr 1864

- 2nd Minnesota Sharpshooters Company Jan 1862

- 1st Minnesota Heavy Nov 1864

- 1st Minnesota Light Artillery Battery Nov 1861

- 2nd Minnesota Light Artillery Battery Mar 1862

- 3rd Minnesota Light Artillery Battery Feb 1863

- 1st Minnesota Cavalry Oct-Dec 1862

- 2nd Minnesota Cavalry Regiment Dec 1863

- 1st Minnesota Light Cavalry(Bracket's Battalion) Sep-Nov 1861

- Minnesota Independent Cavalry Battalion (Hatch's Battalion) Jul 1863

During the Dakota War of 1862, the Army created an internment camp on the flats below the fort for hundreds of Dakota women, children, and elders through the winter of 1862–63. Hundreds died there due to the harsh conditions, weather, and disease.[16] The following year the Dakota that survived were loaded onto steamboats and taken as far as they could on the Minnesota River enroute to Crow Creek Reservation in Southeastern South Dakota. More died on the way. Those that made it to Crow Creek were forced to move again three years later to the Santee Sioux Reservation in Nebraska. Today there stands a memorial on the river flats outside of the Fort Snelling State Park visitor center commemorating those Dakota people that died through this period.[17] After the war, Steele leased the land around Fort Snelling to settlers, and Minneapolis began to expand into the fort's surroundings.[18]

The United States Army assigned the 3rd Infantry to garrison th Fort from 1877-1898. The fort dispatched troops to protect the interests of European-American pioneers on the frontier from the Dakota people, westward to the Rocky Mountains. Besides the Indian Wars soldiers from the garrison fought in the Spanish–American War of 1898.[4] From 1882 until 1888 several Companies of buffalo soldiers from the 25th Infantry were garrisoned at the fort. During one of the last battles of the Indian Wars, six soldiers of the 3rd Infantry from the Fort were killed at the Battle of Leech Lake October 5, 1898. Those killed were Major Wilkinson, Sgt. William Butler, Privates: Edward Lowe, John Olmstead(Onstead), John Schwolenstocker (aka Daniel F. Schwalenstocker), and Albert Ziebel. The soldiers were buried at Northern end of the Post Ft Snelling Minn.[19] Ten other soldiers were wounded in the battle. Among them were five Minnesotans, Privates; George R. Wicker, Charles M. Turner, Edward Brown, Jes S. Jensen, and Gottfried Ziegler. [20]

During World War II 300,000 enlistees were processed at the Fort. The War Department chose Fort Snelling as the location for the Military Intelligence Service Language School to teach the Japanese language to Army personnel. The War Department constructed scores of buildings at the Fort for housing and teaching during the war.[4][12] The Language school was relocated to Monterey, California, in June 1946.[21]

Second decommissioning

The War Department decommissioned Fort Snelling on 14 October 1946, and various federal agencies took parcels from the grounds of the old fort. The majority of the structures fell into disrepair. In 1960, the fort was listed as a National Historic Landmark, citing its importance as the first major military post in the region, and its later history in the development of the United States Army.[2][22]

Fort Snelling continued to serve as headquarters of United States Army Reserve 205th Infantry Brigade, which comprised three light infantry battalions and attached field artillery, cavalry, air defense artillery, combat engineers, and supporting logistics units throughout the Upper Midwest. The Defense Department deactivated this unit in 1994 as a part of force-structure eliminations. Over the decades, the Army interred many deceased Minnesotan soldiers and other members of the United States Armed Forces at Fort Snelling National Cemetery. Some military facilities continue to operate around old Fort Snelling.

The fort has been reconstructed to replicate its original appearance. The Minnesota Historical Society has made the original walled fort into an interactive interpretive center. It is staffed from spring to early fall with personnel attired for re-enacting early post life. Although restoring the original fort assures its survival for the foreseeable future, many buildings constructed from the Indian Wars to WWII have fallen into serious disrepair and neglect. In May 2006, the National Trust for Historic Preservation added Upper Post of Fort Snelling to its list of "America's Most Endangered Places". Some restoration on historic Fort Snelling continues. Crews removed the flagpole from the iconic round tower and installed it in the ground, a change since its opening as a historic fort. Pending funding, the historic fort has planned a massive renovation project for the year 2020. The United States Navy named an amphibious warfare ship, the USS Fort Snelling (LSD-30), to honor the fort.

Notes

See also

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 15, 2006.

- "Fort Snelling". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- Feshir, Riham (April 20, 2016). "Historic Fort Snelling named 'national treasure'". MPR News. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- "Historic Fort Snelling: A Brief History of Fort Snelling". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- Colbruno, Michael "Lives of the Dead: Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland." December 12, 2009. Retrieved March 5, 2015..

- Winstead, 2009

- Patricia Condon Johnston, "Seth Eastman: The Soldier Artist", PBS, accessed 11 December 2008

- "Seth Eastman". United States Army Center of Military History. December 1, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- "Seth Eastman", Library: History Topics, Minnesota Historical Society, 2011, accessed 3 February 2011

- "West Point, New York by Seth Eastman", with bio, US Senate, accessed 29 September 2009

- "Franklin Steele". History of Hennepin County and The City of Minneapolis, 1881. North Star Publishing. p. 635. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "Fort Snelling State Park Upper Bluff Reuse Study" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. November 1998. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) ()

- "Dred and Harriet Scott in Minnesota | MNopedia". www.mnopedia.org. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- "Enslaved African Americans and the Fight for Freedom". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- "The Civil War". Historic Fort Snelling. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- "Forced Marches & Imprisonment". The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- Referenced from the photo Wokiksuye K'a Woyuonihan on the right hand side of the page

- "Urban Connections – Minneapolis". USDA Forest Service. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- Obituaries, St Paul Globe October 9, 1898.p.3: Wilkinson [Section A-25/Site 6705]; Lowe [Section A-5/Site 607]; Onstead [Section A-25/6618]; Schwalenstocker [Section A-5/Site 644] and Ziebel [Section A-5/Site 648] in the National Cemetery. Butler was reburied at Palmyra, Michigan, Minnesota Historical Society, St Paul, Mn

- See Holbrook, Franklin F., Minnesota War Records, 1923 & The Deteriorating Upper Post of Ft. Snelling, http://celticfringe.net/history/upper_post.htm

- Yamashita, Jeffrey T. "Fort Snelling" Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved on July 3, 2014.

- Marilynn Larew (March 15, 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Fort Snelling" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-06-21. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) and Accompanying 29 images, including photos from late 1880s to 1977. (6.55 MB)

Other sources

- Winstead, Tim (2009). "John Taylor Wood: Man of Action, Man of Honor".

Wilmington, North Carolina: The Cape Fear Civil War Round Table. Retrieved Oct 7, 2013.

Further reading

- Anfinson, John O. (2003). River of History: A Historic Resources Study of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. St. Paul District, Corps of Engineers.

- DeCarlo, Peter. Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017). 96 pp.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Snelling. |

- Round Tower, Fort Snelling in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

- Three Score Years and Ten – Life-Long Memories of Fort Snelling, Minnesota, and other parts of the West, by Charlotte Ouisconsin Van Cleve. Published in 1888, from Project Gutenberg

- Fort Snelling National Cemetery, Department of Veterans Affairs Official webpage

- Minneapolis VA Medical Center, Department of Veterans Affairs Official webpage

- Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport Official website

- NHL summary

- National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form – includes description and details on buildings

- Historic Fort Snelling page of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area's website