Erlkönig (Goethe)

"Erlkönig" is a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. It depicts the death of a child assailed by a supernatural being, the Erlking, a kind of demon or king of the fairies. It was originally written by Goethe as part of a 1782 Singspiel, Die Fischerin.

"Erlkönig" has been called Goethe's "most famous ballad".[1] The poem has been set to music by several composers, most notably by Franz Schubert.

Summary

An anxious young boy is being carried at night by his father on horseback. To where is not spelled out; German Hof has a rather broad meaning of "yard", "courtyard", "farm", or (royal) "court". The opening line tells that the time is unusually late and the weather unusually inclement for travel. As it becomes apparent that the boy is delirious, a possibility is that the father is rushing him to medical aid.

As the poem unfolds, the son claims to see and hear the "Erlkönig" (Elf King). His father claims to not see or hear the creature, and he attempts to comfort his son, asserting natural explanations for what the child sees – a wisp of fog, rustling leaves, shimmering willows. The Elf King attempts to lure the child into joining him, promising amusement, rich clothes and attentions of his daughters. Finally the Elf King declares that he will take the child by force. The boy shrieks that he has been attacked, spurring the father to ride faster to the Hof. Upon reaching the destination, the child is already dead.

Text

| Literal translation | Edgar Alfred Bowring[2] | |

|---|---|---|

Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind? |

Who rides, so late, through night and wind? |

Who rides there so late through the night dark and drear? |

The legend

The story of the Erlkönig derives from the traditional Danish ballad Elveskud: Goethe's poem was inspired by Johann Gottfried Herder's translation of a variant of the ballad (Danmarks gamle Folkeviser 47B, from Peter Syv's 1695 edition) into German as Erlkönigs Tochter ("The Erl-king's Daughter") in his collection of folk songs, Stimmen der Völker in Liedern (published 1778). Goethe's poem then took on a life of its own, inspiring the Romantic concept of the Erlking. Niels Gade's cantata Elverskud, Op. 30 (1854, text by Chr. K. F. Molbech) was published in translation as Erlkönigs Tochter.

The Erlkönig's nature has been the subject of some debate. The name translates literally from the German as "Alder King" rather than its common English translation, "Elf King" (which would be rendered as Elfenkönig in German). It has often been suggested that Erlkönig is a mistranslation from the original Danish elverkonge, which does mean "king of the elves."

In the original Scandinavian version of the tale, the antagonist was the Erlkönig's daughter rather than the Erlkönig himself; the female elves or Danish elvermøer sought to ensnare human beings to satisfy their desire, jealousy and lust for revenge.

Settings to music

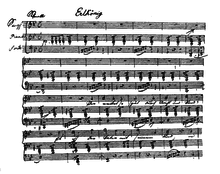

The poem has often been set to music with Franz Schubert's rendition, his Opus 1 (D. 328), being the best known.[3][4] Probably the next best known is that of Carl Loewe (1818). Other notable settings are by members of Goethe's circle, including the actress Corona Schröter (1782), Andreas Romberg (1793), Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1794) and Carl Friedrich Zelter (1797). Ludwig van Beethoven attempted to set it to music but abandoned the effort; his sketch however was complete enough to be published in a completion by Reinhold Becker (1897). A few other 19th-century versions are those by Václav Tomášek (1815) and Louis Spohr (1856, with obbligato violin) and Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (Polyphonic Studies for Solo Violin). Twenty-first-century examples are pianist Marc-André Hamelin's "Etude No. 8 (after Goethe)" for solo piano, based on "Erlkönig".[5]

The Franz Schubert composition

Franz Schubert composed his Lied "Erlkönig" for solo voice and piano at the age of 17 or 18 in 1815, setting text from Goethe's poem. Schubert revised the song three times before publishing his fourth version in 1821 as his Opus 1; it was catalogued by Otto Erich Deutsch as D. 328 in his 1951 catalog of Schubert's works. The song was first performed in concert on 1 December 1820 at a private gathering in Vienna and received its public premiere on 7 March 1821 at Vienna's Theater am Kärntnertor.

The four characters in the song – narrator, father, son, and the Erlking – are all sung by a single vocalist. Schubert places each character largely in a different vocal range, and each has his own rhythmic nuances; in addition, most singers endeavor to use a different vocal coloration for each part.

- The Narrator lies in the middle range and begins in the minor mode.

- The Father lies in the lower range and sings in both minor and major mode.

- The Son lies in a higher range, also in the minor mode.

- The Erlking's vocal line, in the major mode, provides the only break from the ostinato bass triplets in the accompaniment until the boy's death.

A fifth character, the horse, is implied in rapid triplet figures played by the pianist throughout the work, mimicking hoof beats.[6]

"Erlkönig" starts with the piano playing rapid triplets to create a sense of urgency and simulate the horse's galloping. The left hand of the piano part introduces a low-register leitmotif composed of rising scale in triplets and a falling arpeggio. The moto perpetuo triplets continue throughout the entire song except for the final three bars and mostly comprise the uninterrupted repeated chords or octaves in the right hand, established at the opening. Significantly, the Erlkönig's verses differ in their accompanying figurations (providing some relief for the pianist) but are still based on triplets.

Each of the Son's pleas becomes higher in pitch. Near the end of the piece, the music quickens and then slows as the Father spurs his horse to go faster and then arrives at his destination. The absence of the piano creates multiple effects on the text and music. The silence draws attention to the dramatic text and amplifies the immense loss and sorrow caused by the Son's death.

The song has a tonal scheme based on rising semitones which portrays the increasingly desperate situation:

| Verse | Tonality | Character |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | G minor | Narrator |

| 2 | G minor → B♭ major | Father and Son |

| 3 | B♭ major | Erl-King |

| 4 | (D7) → B minor | Son |

| → G major | Father | |

| 5 | C major | Erl-King |

| 6 | (E7) → C♯ minor | Son |

| D minor | Father | |

| 7 | E♭ major → D minor | Erl-King |

| (F7) → G minor | Son | |

| 8 | G minor | Narrator |

The 'Mein Vater, mein Vater' music appears three times on a prolonged dominant seventh chord that slips chromatically into the next key. Following the tonal scheme, each cry is a semitone higher than the last, and, as in Goethe's poem, the time between the second two cries is less than the first two, increasing the urgency like a large-scale stretto. Much of the major-key music is coloured by the flattened submediant, giving it a darker, unsettled sound.

The piece is regarded as extremely challenging to perform due to the multiple characters the vocalist is required to portray, as well as its difficult accompaniment, involving rapidly repeated chords and octaves which contribute to the drama and urgency of the piece.

"Erlkönig" is through-composed; although the melodic motives recur, the harmonic structure is constantly changing and the piece modulates within characters. The rhythm of the piano accompaniment also changes within the characters. The first time the Erl-king sings in measure 57, the galloping motive disappears. However, when the Erlking sings again in measure 87, the piano accompaniment plays arpeggios rather than chords.

"Erlkönig" has been transcribed for various settings: for solo piano by Franz Liszt; for solo voice and orchestra by Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt and Max Reger; for solo violin by Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst.

The Carl Loewe composition

Carl Loewe's setting was published as Op. 1, No. 3 and composed in 1817–18, in the lifetime of the poem's author and also of Schubert, whose version Loewe did not then know. Collected with it were Op. 1, No. 1, "Edward" (1818; a translation of the Scottish ballad), and No. 2, "Der Wirthin Töchterlein" (1823; "The Innkeeper's Daughter"), a poem of Ludwig Uhland. Inspired by a German translation of Scottish border ballads, Loewe set several poems with an elvish theme; but although all three of Op. 1 are concerned with untimely death, in this set only the "Erlkönig" has the supernatural element.

Loewe's accompaniment is in semiquaver groups of six in 9

8 time and marked Geschwind (fast). The vocal line evokes the galloping effect by repeated figures of crotchet and quaver, or sometimes three quavers, overlying the binary tremolo of the semiquavers in the piano. In addition to an unusual sense of motion, this creates a flexible template for the stresses in the words to fall correctly within the rhythmic structure.

Loewe's version is less melodic than Schubert's, with an insistent, repetitive harmonic structure between the opening minor key and answering phrases in the major key of the dominant, which have a stark quality owing to their unusual relationship to the home key. The narrator's phrases are echoed by the voices of father and son, the father taking up the deeper, rising phrase, and the son a lightly undulating, answering theme around the dominant fifth. These two themes also evoke the rising and moaning of the wind.

The Erl-king, who is always heard pianissimo, does not sing melodies, but instead delivers insubstantial rising arpeggios that outline a single major chord (that of the home key) which sounds simultaneously on the piano in una corda tremolo. Only with his final threatening word, "Gewalt", does he depart from this chord. Loewe's implication is that the Erlking has no substance but merely exists in the child's feverish imagination. As the piece progresses, the first in the groups of three quavers is dotted to create a breathless pace, which then forms a bass figure in the piano driving through to the final crisis. The last words, war tot, leap from the lower dominant to the sharpened third of the home key; this time not to the major but to a diminished chord, which settles chromatically through the home key in the major and then to the minor.

See also

References

- Purdy, Daniel (2012). Goethe Yearbook 19. Camden House. p. 4. ISBN 1571135251.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1853). "The Erl-King". The Poems of Goethe. translated by Edgar Alfred Bowring. p. 99.

- Snyder, Lawrence (1995). German Poetry in Song. Berkeley: Fallen Leaf Press. ISBN 0-914913-32-8. contains a selective list of 14 settings of the poem

- "Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind?". The LiederNet Archive. Retrieved 8 October 2008. lists 23 settings of the poem

- Hamelin's "Erlkönig" on YouTube

- Machlis, Joseph and Forney, Kristine. "Schubert and the Lied" The Enjoyment of Music: An Introduction to Perceptive Listening. 9th Ed. W. W. Norton & Company: 2003

- Moser, Hans Joachim (1937). Das deutsche Lied seit Mozart. Berlin & Zurich: Atlantis Verlag.

- Loewe, Carl. Friedlaender, Max; Moser, Hans Joachim (eds.). Lieder. Leipzig: Edition Peters.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| German Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erlkönig (Goethe). |

- Translation by Matthew Lewis

- Translation at Poems Found in Translation

- Songwriter Josh Ritter performs his translation of the poem, titled "The Oak King" on YouTube

- "Erlkönig" (Schubert) on YouTube, orchestrated by Max Reger; Teddy Tahu Rhodes, Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra, Sebastian Lang-Lessing

- "Erlkönig" at Emily Ezust's Lied and Art Song Texts Page; translation and list of settings

- Adaptation by Franz Schubert free recording (mp3) and free score

- Schubert's setting of "Erlkönig": Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Carl Loewes's 3 Ballads, Op. 1 (No. 3: "Erlkönig"): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Full score and MIDI file of Schubert's setting of "Erlkönig" from the Mutopia Project

- Goethe and the Erlkönig Myth

- Audio for Earlkings legacy (3:41 minutes, 1.7 MB), performed by Christian Brückner and Bad-Eggz, 2002.

- Paul Haverstock reads Goethe's "Erlkönig" with background music on YouTube

.jpg)