Egypt–France relations

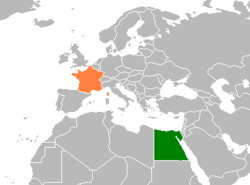

Egypt-France relations refers to the bilateral relationship between the Arab Republic of Egypt and the French Republic. Relations between the two countries have spanned centuries, from the Middle Ages to the present day. Following the French occupation of Egypt (1798-1801), a strong French presence has remained in Egypt. Egyptian influence is also evident in France, in monuments such as the Luxor Obelisk in Paris. The relationship is also marked by conflicts like the Algerian War (1954-1962) and the Suez Crisis (1956). As of 2020, relations are strong and consist of shared cultural activities such as the France-Egypt Cultural Year (2019), tourism, diplomatic missions, trade, and a close political relationship. Institutions like the Institut d’Égypte, the French Institute in Egypt and the French University of Egypt (UFE) also aid in promoting cultural exchange between Egypt and France.

| |

Egypt |

France |

|---|---|

History

Sixteenth century

France had signed a first treaty or Capitulation with the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt in 1500, during the rules of Louis XII and Sultan Bajazet II,[1][2] in which the Sultan of Egypt had made concessions to the French and the Catalans, and which would be later extended by Suleiman the Magnificent.

French occupation of Egypt

Between 1798-1801 Napoleon Bonaparte commanded a French campaign to occupy Egypt. This was possible due to the unstable political situation in Egypt.[3] The objectives of the campaign were to cut off Britain’s trade route to India and to establish French trade in the Middle East.[4] Early in the occupation, the French established mass political and social reforms in Egypt, such as the founding of a new governing body called the Diwan, and reconstructing many of the large cities.[5]

On Napoleon’s orders the Insitut D’Égypte was created in 1798 as a replication of the Institut National de France, to encourage study of Egypt by French scholars.[6] The Institut D’Égypte published the first newspapers in Egypt, Le Courier de l’Égypte and La Décade Égyptienne.[5]

Following Napoleon’s departure from Egypt in 1799, the French occupiers in Egypt became divided into two factions: Republicans favouring withdrawal from Egypt, and Colonialists wanting to maintain the French presence in Egypt.[7] The colonial effort soon collapsed, and by 1801 French forces had abandoned Egypt.[7]

The Rosetta Stone was discovered during French occupation in Egypt in 1799.[8] It was found in the Egyptian city of Rosetta (Rashid).[8] Although accounts of the exact circumstances under which it was found differ, it is generally accepted that French soldiers discovered it by accident while building a fort in the Nile Delta.[8] After Napoleon’s defeat, the Rosetta Stone was seized by Britain, under terms of the Treaty of Alexandria in 1801.[8] It is now housed in the British Museum in London.[8]

Luxor Obelisk

The Luxor Obelisk (Obélisque du Louxor) is an ancient Egyptian obelisk that is situated in the Place de la Concorde in Paris.[9] Over 3,300 years old, the obelisk is inscribed with hieroglyphs that detail the rule of Pharaohs Rameses II and Rameses III.[10] In 1829 it was gifted to France by Muhammad Ali, also known as Mehmet Ali Pesha, the first governor of Egypt.[9][10] It arrived in Paris in 1833, and was erected in the Place de la Concorde where it still stands.[10] It is made of red granite and is 22.5 metres tall, weighing over 200 tons.[9] It was originally one of two obelisks that stood at the Luxor Temple in the ancient city of Thebes, now Luxor, in Egypt.[10] Its pair remains at the temple there.[9]

Suez Canal

In 1858, the Universal Company of the Maritime Suez Canal, or Suez Canal Company, was formed by French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps to build the Suez Canal, beginning construction on April 25 1859.[11] Although Napoleon had originally conceived the idea to build the canal in 1799, the project never came to fruition. The Suez Canal Company was granted permission to construct the canal and operate the canal for 99 years, when its control would be returned to the Egyptian government.[11] Shares in the company were originally divided primarily between French and Egyptian parties, however, the British government purchased Egypt’s shares in 1875, resulting in French and British control of the canal.[11] Control of the canal remained contested, and in July 1956 it was nationalised by the Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser.[11] British, French and US leaders agreed to create an associate to control the canal, but Nasser refused to comply with the agreement.[12] In October 1956, the United Nations Security Council proposed a resolution to prevent the use of force over the Suez Canal issue, but it was vetoed by France and Britain.[12] Alongside Israel, Britain and France attacked Egypt in October 1956.[13] This was followed by an aerial bombardment of Suez by British and French forces in November 1956.[14]

Independence Movements in North Africa

After World War II, opposition to French imperialism in North Africa grew.[15] The League of Arab States was founded in 1945 with independence of Arab nations as one of its key aims.[16] The Committee for the Liberation of North Africa, an organisation funded by the League of Arab States, established its headquarters in Cairo.[16] In 1947, Moroccan and Algerian nationalists established the Arab Maghrib Bureau in Cairo, with the intent of creating anti-French propaganda.[15] From 1954-1962, the Algerian War was fought for Algeria’s independence from French rule. During the war, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser was a strong vocal supporter of the resistance movement and provided military aid to the National Liberation Front (FLN).[17] Egypt supplied the Algerian rebels with military equipment and training soldiers.[16] In 1956, France asked the Security Council of the United Nations to outlaw external aid to the FLN in Algeria.[18] This was targeted towards Egypt’s supply of military equipment to Algerian rebels, via a ship that had been intercepted by the French navy.[19] Before the issue was addressed by the Security Council, French and British forces invaded the Suez Canal in Egypt.[19] The issue was transferred to the General Assembly, which ruled that France and the United Kingdom should withdraw from Egypt, as the United Nations found that the Egyptian supply of arms to Algeria did not warrant such retaliation.[19] For France, Suez had mostly been about Algeria, and traditional narratives therefore argue that the Egyptian victory following the crisis bolstered the FLN's cause.[20]

Arab Spring

.jpg)

In 2010, a series of anti-government protests arose across the Middle East and North Africa, becoming what is known as the Arab Spring.[21] The pro-democracy protests led to the collapse of governments in Tunisia, Libya, Yemen and Egypt.[21] The breakdown of authoritarian governments in the MENA region posed a series of problems to Europe and the United States.[22] For example, the loss of former authoritarian allies, concerns that prices of oil would increase and a fear that an influx of illegal migrants would arrive in Europe from the Middle East.[22]

On January 25, 2011, a series of protests broke out in Cairo, demanding that President Hosni Mubarak leave office.[21] Before the protests broke out, Mubarak was considered a close ally to the United States and Europe.[23] The United States swayed its support between the Mubarak regime and the Egyptian people, before arguing that Mubarak should step down, a sentiment that was soon echoed by France, Germany, Britain, Italy and Spain.[23]

Cultural relations

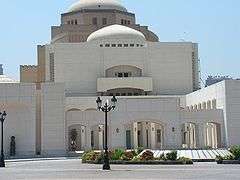

France-Egypt Cultural Year

In an effort to promote cultural exchange, 2019 was declared the France-Egypt Cultural Year, celebrating the 150th anniversary of the opening of the Suez Canal and coinciding with French President Emmanuel Macron’s official visit to Egypt.[24] The activities of the year were coordinated by the Institut Français in Cairo and the Egyptian Cultural Centre in Paris. The Minister of Culture for Egypt Ines Abdel-Dayem and the French Ambassador to Egypt Stéphane Romatet held a press conference on the 8th of January to discuss the events of the year.[25] Romatet said that the festivities would contribute to “strengthening the bilateral relations and exchanging the experiences and activities between the two countries in all cultural and artistic fields.”[25] The festivities commenced on the 8th of January 2019 at the Cairo Opera House with an opening show featuring dancers from the Paris and Cairo Operas.[24] This was the first of four concerts featuring the ‘Independanse x Egypte’ dance show, held at both the Cairo and Alexandria opera houses.[25] The show was choreographed by Grégory Gaillard, including music by Florent Astrudeau, which was inspired by the Nile River.[25] Events were held throughout the year in both Egypt and France and consisted of operas, musical and dance performances, exhibitions of art and historical artefacts, as well as celebrations of French culinary.[26]

Tourism

In 2019, around 700,000 French tourists visited Egypt.[27] French Ambassador to Egypt Stéphane Romatet stated in 2019 that he is devoted to promoting Egypt in France, saying that he believes that numbers of French tourists travelling to Egypt will increase in 2020.[27] Egypt was ranked the world's 4th fastest growing tourism destination in 2019.[28]

Diplomatic relations

Egypt is represented in France through the Egyptian Embassy in Paris, the Consulate General in Marseille and the Consulate in Paris.[29] From 2016, Ehab Badawy has served as the Egyptian Ambassador to France.[30] France is represented in Egypt through the French Embassy in Cairo, and Consulate-Generals in Cairo and Alexandria. As of 2020, the French Ambassador to Egypt is Stéphane Romatet.[31]

Embassy of Egypt in Paris

Embassy of Egypt in Paris Consulate-General of Egypt in Paris

Consulate-General of Egypt in Paris- Consulate-General of France in Alexandria

Official state visits are frequent between the two countries. In January 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron visited Egypt for an official three-day visit.[32] In August 2019, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi visited France for the G7 Summit.[32] President Sisi also travelled to France for official state visits in 2017.[32]

Education relations

The Institut d'Égypte

.jpg)

The Institut d’Égypte or Egyptian Scientific Institute was established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 to facilitate French scholarship in Egypt.[6] In 2011, the Institute caught fire during protests, and 192,000 books and journals were damaged or lost.[33] This included the 24-volume Description de l’Égypte or Description of Egypt, a handwritten work that contained observations by over 150 French scholars and scientists begun between 1798-1801 during French occupation in Egypt. In 2012, the Institute was reopened after extensive restoration.[34] Works that had not been damaged in the fire were returned, as well as donated collections.[34] The restored Institute is two levels.[35] The first houses a reading area complete with computers, and the second level comprises lecture and seminar halls, meeting rooms, a lounge for high-profile guests, an event hall and a main hall which includes the library.[35]

Institut Français d’Égypte

The Institut Français d’Égypte or the French Institute in Egypt was established in 1967. It currently has four branches across Egypt, with three in Cairo (Mounira, Heliopolis and New Cairo) as well as one in Alexandria.[36] A new branch in Sheikh Zayed in Greater Cairo is expected to open in 2020.[36] According to its website, the Institute's mission is to "contribute to the influence of French culture, language and expertise in Egypt" and to improve relations between Egypt and France in the areas of education, linguistics, culture, science and technology.[36]

Université Française d’Égypte

The Université Française d’Égypte (UFE), or the French University of Egypt, was established in Cairo in 2002.[37] It offers courses in Arabic, English and French and encourages students to study overseas in France. The interim President Dr Taha Abdallah described the university as “a private scientific, cultural and professional establishment”.[37]

Economic relations

Trade

A €5.2 billion deal was signed by the Egyptian administration in 2015 for the purchase of fighter jets, missiles, and a frigate from France.[38] In 2016, Egypt purchased military equipment including fighter jets, warships and a military satellite from France in a deal worth more than €1 billion.[38] In 2017, trade between Egypt and France increased by 21.8%, totalling €2.5 billion after a 27.5% decrease in trade each year between 2006-2016 between the two countries.[32] For the fiscal year 2016-2017, France was ranked as Egypt’s 11th largest trade partner.[32] According to the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, French companies have a significant role in the Egyptian economy, in industries such as pharmaceuticals, electrical equipment, tourism and infrastructure.[32]

Controversies and disputes

French President Emmanuel Macron has faced criticism over his promotion of trade relations between the two countries, from the public as well as organisations like Amnesty International.[40] This was in reference to a €5.2 billion deal signed in 2015, in which France sold fighter jets, missiles and a frigate to Egypt.[38] Amnesty International allege that France’s supply of arms violates international law, and that the weapons supplied had been used to violently shut down to protests.[41] At a joint press conference during Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s visit to Paris in 2017, President Macron was asked to comment on Egypt’s alleged abuse of human rights. He said that it was not his place to “lecture” his counterpart on such matters.[42] The matter resurfaced during Macron’s official visit to Egypt in 2019, where discussions over human rights again dominated a press conference between him and President Sisi. Macron stated that stability cannot be separated from human rights.[42] President Sisi responded that it was inappropriate to view Egypt and its issues from a European perspective, saying “We are not Europe”.[43]

References

- Three years in Constantinople by Charles White p.139

- Three years in Constantinople by Charles White p.147

- Coller, Ian (2013). The French Revolution in Global Perspective. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 122. doi:10.7591/j.ctt1xx62b.12#metadata_info_tab_contents (inactive 2020-06-03). ISBN 978-0-8014-5096-9. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1xx62b.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- "Napoleon in Egypt". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Coller, Ian (2013). The French Revolution in Global Perspective. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 127. doi:10.7591/j.ctt1xx62b.12 (inactive 2020-06-03). ISBN 978-0-8014-5096-9. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1xx62b.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- "The 'Institut d'Égypte' and the Description de l'Égypte". napoleon.org. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Coller, Ian (2013). The French Revolution in Global Perspective. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 128. doi:10.7591/j.ctt1xx62b.12 (inactive 2020-06-03). ISBN 978-0-8014-5096-9. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1xx62b.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- "Everything you ever wanted to know about the Rosetta Stone". The British Museum Blog. 2017-07-14. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Luxor Obelisk - Place de la Concorde, Paris". Archaeology Travel. 2017-05-23. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Luxor Obelisk monument in Paris France". www.eutouring.com. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "SCA - Canal History". www.suezcanal.gov.eg. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Sharma, Jagdish P. (1997). "Globalization in Historical Context: A Case Study of Suez". Pakistan Horizon. 50 (2): 67. ISSN 0030-980X. JSTOR 41393572.

- Sharma, Jagdish P. (1997). "Globalization in Historical Context: A Case Study of Suez". Pakistan Horizon. 50 (2): 57–73. ISSN 0030-980X. JSTOR 41393572.

- "BBC - History - British History in depth: The Suez Crisis". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Johnson, Jennifer; Lockwood, Bert B. (2016). The Battle for Algeria: Sovereignty, Health Care, and Humanitarianism. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8122-4771-8. JSTOR j.ctt18z4g2g.

- Fraleigh, Arnold (1967). "The Algerian War of Independence". Proceedings of the American Society of International Law at Its Annual Meeting (1921-1969). 61: 8. doi:10.1017/S0272503700010879. ISSN 0272-5045. JSTOR 25657708.

- Aburish 2004, pp. 209–211

- Fraleigh, Arnold (1967). "The Algerian War of Independence". Proceedings of the American Society of International Law at Its Annual Meeting (1921-1969). 61: 10–11. doi:10.1017/S0272503700010879. ISSN 0272-5045. JSTOR 25657708.

- Fraleigh, Arnold (1967). "The Algerian War of Independence". Proceedings of the American Society of International Law at Its Annual Meeting (1921-1969). 61: 11. doi:10.1017/S0272503700010879. ISSN 0272-5045. JSTOR 25657708.

- Vivian Ibrahim (November 24, 2009). "Algeria and Egypt: A tale of two histories". Egypt Independent.

- "What was the Arab Spring and what caused it to happen?". National Geographic. 2019-03-29. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Metawe, Mohamed (2013). "How and Why the West Reacted to the Arab Spring: An Arab Perspective". Insight Turkey. 15 (3): 142. ISSN 1302-177X. JSTOR 26299492.

- Metawe, Mohamed (2013). "How and Why the West Reacted to the Arab Spring: An Arab Perspective". Insight Turkey. 15 (3): 145. ISSN 1302-177X. JSTOR 26299492.

- "Launch of the France-Egypt Cultural Year (10.01.19)". Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- El-Adawi, Reham. "Cultural events held to celebrate 'Egypt-France Cultural Year' - City Lights - Arts & Culture". Ahram Online. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "FRANCE EGYPT 2019 Cultural Year". institutfrancais-egypte.com. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Mira, Maged (2019-12-27). "700,000 French tourists visited Egypt in 2019: French ambassador". Egypt Independent. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Egypt is the World's 4th Fastest Growing Tourist Destination: AFAR Magazine". Egypt Independent. 2019-11-15. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Représentations étrangères en France". France Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Egypt | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". UNESCO. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Biographie de l'Ambassadeur". La France en Égypte (in French). Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Egypt". France Diplomacy - Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Cairo institute burned during clashes". The Guardian. 2011-12-19. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Al-Youm, Al-Masry (2012-10-22). "Institut d'Egypte reopened following restoration". Egypt Independent. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- al-Khair, Waleed Abu (2013). "Egypt's Scientific Institute comes back to life". Culture in Development. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "L'Institut français d'Égypte". institutfrancais-egypte.com. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "University – l'Université Française d'Egypte". Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- "Egypt's human rights abuses overshadow Macron's visit". France 24. 2019-01-28. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Egypt". European Commission. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Global indifference to human rights violations in MENA fuelling atrocities and impunity". Amnesty International. 2019-02-26. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Egypt: France flouts international law by continuing to export arms used in deadly crackdowns". Amnesty International. 2018-10-16. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Macron risks new criticism over human rights with lucrative trip to Egypt". France 24. 2019-01-27. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "Sisi gives firm response to concerns over human rights in Egypt". Egypt Today. 2019-01-28. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

External links

- Egypt-France sis.gov.e.g.

.svg.png)