Die Hard

Die Hard is a 1988 American action film directed by John McTiernan and written by Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza. It stars Bruce Willis, Alan Rickman, Alexander Godunov, and Bonnie Bedelia. Based on the 1979 novel Nothing Lasts Forever by Roderick Thorp, Die Hard follows New York City police detective John McClane (Willis) who is caught up in a terrorist takeover of a Los Angeles skyscraper while visiting his estranged wife. The film features Reginald Veljohnson, William Atherton, Paul Gleason, and Hart Bochner in supporting roles.

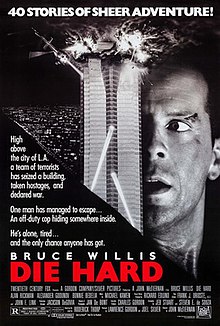

| Die Hard | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John McTiernan |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Nothing Lasts Forever by Roderick Thorp |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Michael Kamen |

| Cinematography | Jan de Bont |

| Edited by | |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 132 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25–35 million |

| Box office | $139.8–141.5 million |

Desperate for work, Stuart was offered the job of adapting Thorp's novel into a screenplay. His finished draft was greenlit immediately by 20th Century Fox, which was eager for a summer blockbuster for the following year. Finding a star proved difficult: the role of McClane was offered to a host of the decade's top stars, including Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, all of whom turned it down. Willis, who was known mainly for his TV work, was not the studio's first choice for the role. He was paid $5 million for the role, an unheard-of figure at the time. Filming began in November 1987 on a $25 million–$35 million budget. The script underwent changes throughout filming, including adding and changing scenes, and altering the ending. Die Hard was filmed almost entirely on location in and around Fox Plaza in Los Angeles.

Die Hard was a box office success, grossing between $139.8 million–$141.5 million, and defying pre-release expectations that Willis' lack of star appeal would hurt the film's success. It was the tenth highest-grossing film of 1988 and the highest-grossing action film. Initial reviews were mixed: criticism was levelled at the violence, plot, and Willis' performance, while McTiernan's direction and Rickman's charismatic portrayal of the villain Hans Gruber were praised. Die Hard received four Academy Award nominations. The film elevated Willis to leading-man status and took Rickman from relative obscurity to celebrity.

In the wake of its release, Die Hard has been critically re-evaluated and is now considered to be one of the greatest action and Christmas films ever made. It revitalized the action genre, largely due to its depiction of McClane as a vulnerable and fallible protagonist, in contrast to the muscle-bound and invincible action heroes of its contemporaries. The film's success spawned a host of imitators, such that the term "Die Hard in/on a..." became a shorthand way of describing a film's plot, particularly one where a lone hero must fight overwhelming odds, often in a restricted environment. Die Hard is the first film in what would become the Die Hard franchise, that includes four film sequels—Die Hard 2, Die Hard with a Vengeance, Live Free or Die Hard, and A Good Day to Die Hard—video games, comic books, toys, board games, clothing, and collectibles. Deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress, the film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2017.

Plot

On Christmas Eve 1988, NYPD Detective John McClane arrives in Los Angeles intending to reconcile with his estranged wife, Holly. He is driven to Nakatomi Plaza by his driver, Argyle, to attend a Christmas party held by Holly's employer, the Nakatomi Corporation; Argyle waits for McClane in the garage. While McClane changes clothes, the tower is seized by a German radical, Hans Gruber and his heavily armed team: Karl and his brother Tony, Franco, Theo, Alexander, Marco, Kristoff, Eddie, Uli, Heinrich, Fritz, and James. Those inside the tower are taken hostage, except for McClane, who slips away.

Gruber interrogates Nakatomi executive Joseph Takagi for the building's vault code. Gruber reveals that he plans to steal $640 million (equivalent to $1.38 billion in 2019) in untraceable bearer bonds. The gang is pretending to be terrorists to conceal the theft. Takagi refuses to cooperate and is executed; Theo is tasked with breaking into the vault. McClane, who is secretly watching events, triggers a fire alarm to alert authorities. Tony is sent after McClane, who kills him, obtaining his weapon and radio, which he uses to contact the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). Sergeant Al Powell is sent to investigate.

McClane kills Marco and Heinrich, recovering the latter's bag of C-4 explosives and detonators. Seeing nothing amiss, Powell prepares to leave when McClane drops Marco's body onto his patrol car. Powell summons the LAPD; a SWAT team lays siege to the building but are neutralized by gunfire on the ground floor, and anti-tank missiles fired by James and Alexander. McClane throws some C-4 down an elevator shaft. The explosion kills the pair, ending the assault.

Holly's co-worker Harry Ellis attempts to mediate between Gruber and McClane for the latter's surrender. McClane refuses, and Ellis is killed. Gruber checks the explosives installed on the roof and encounters McClane. He portrays himself as an escaped hostage. McClane offers him a gun, and Gruber attempts to shoot him; the gun is empty. Karl, Franco, and Fritz arrive; McClane kills Fritz and Franco, but is badly injured by shattered glass from shot-out office windows, and is forced to flee, abandoning the detonators.

Outside, FBI agents commandeer the situation, ordering the power shut off. As Gruber had anticipated, the power cut disables the final vault lock; his team collects the bonds. Gruber demands a helicopter be flown to the roof. The FBI agrees, intending to send gunship helicopters to eliminate the group, regardless of collateral damage to the hostages.

A despondent McClane contacts Powell. He tells McClane that he accidentally shot a child once while on patrol and has not used his gun since. McClane realizes Gruber intends to detonate the rooftop—killing the hostages and the FBI agents—to fake his team's deaths. Karl confronts McClane and they fight. Gruber sees a news report by reporter Richard Thornburg on McClane's children and deduces that he is Holly's husband. The hostages are escorted to the roof; Gruber keeps Holly with him. During the long fight, McClane seemingly kills Karl. He kills Uli and rescues the hostages just before Gruber detonates the roof, destroying the FBI helicopters. Meanwhile, Theo retrieves their getaway vehicle from the parking garage but is neutralized by Argyle, who has been following the events on his radio.

A weary and battered McClane finds Holly with Gruber and his remaining men, Eddie and Kristoff. After knocking Kristoff unconscious, McClane confronts Gruber and is ordered to surrender his submachine gun. McClane does this to spare Holly but distracts Gruber and Eddie by laughing and grabs a concealed pistol taped to his back that contains two bullets. McClane wounds Gruber and kills Eddie; Gruber crashes through a window but grabs onto Holly's wrist. He makes a last-ditch attempt to kill the pair, but McClane unclasps Holly's wristwatch and Gruber falls to his death on the street below.

Outside, McClane and Holly meet Powell. Karl emerges and attempts to shoot McClane but is killed by Powell. Thornburg arrives and trys to interview McClane, but Holly punches him. Argyle crashes through the parking garage door in the limo and leaves the area with McClane and Holly.

Cast

- Bruce Willis as John McClane, a streetwise New York cop

- Alan Rickman as Hans Gruber, the charismatic leader of the terrorists

- Alexander Godunov as Karl, Hans's second-in-command

- Bonnie Bedelia as Holly Gennero-McClane, a high-ranking Nakatomi executive and John's estranged wife

- Reginald VelJohnson as Al Powell, an LAPD sergeant

- Paul Gleason as Dwayne T. Robinson, the LAPD Deputy Chief

- De'voreaux White as Argyle, John's limousine driver

- William Atherton as Richard Thornburg, an arrogant TV reporter

- Clarence Gilyard as Theo, Hans' tech specialist

- Hart Bochner as Harry Ellis, a sleazy Nakatomi executive

- James Shigeta as Joseph Yoshinobu Takagi, Nakatomi's head executive

Additional cast includes Hans's henchmen: Bruno Doyon as Franco, Andreas Wisniewski as Tony, Joey Plewa as Alexander, Lorenzo Caccialanza as Marco, Gerard Bonn as Kristoff, Dennis Hayden as Eddie, Al Leong as Uli, Gary Roberts as Heinrich, Hans Buhringer as Fritz, and Wilhelm von Homburg as James. Robert Davi and Grand L. Bush appear as FBI Special Agents Big Johnson and Little Johnson, respectively, Tracy Reiner appears as Thornburg's assistant, and Taylor Fry and Noah Land make minor appearances as McClane's children Lucy McClane and John Jr.

Production

Development

The development of Die Hard began in 1987. Screenwriter Jeb Stuart was in dire financial straits and needed paying work. He had successfully pitched a script to Columbia Pictures with Robert Duvall set to star, but the project was abandoned. A separate four-script contract at Walt Disney Pictures was not providing him with sufficient income. After submitting his first contracted script to Disney, Stuart had six weeks when he could complete work for another studio. His agent Jeremy Zimmer contacted Lloyd Levin, the head of development at the Gordon Company.[1]

The Gordon Company worked as a producing arm of 20th Century Fox, and Levin had a property that Stuart could work on—an adaptation of the 1978 novel Nothing Lasts Forever written by former police officer Roderick Thorp.[2][1] Having purchased the adaptation rights to the novel before it had been written, Fox had adapted the book's 1966 predecessor, The Detective, for the 1968 film of the same name starring Frank Sinatra as NYPD detective Joe Leland. The Detective had been considered groundbreaking for its time, showing a more realistic take on police work than other Hollywood fare, and touching on taboo themes like homosexuality and infidelity. Thorp was inspired to write Nothing Lasts Forever after watching the disaster film The Towering Inferno (1974).[1][3]

Levin had attempted to develop the film for several years and offered Stuart the opportunity to do so. He gave Stuart creative freedom as long as he retained the Christmas in Los Angeles setting; Levin wanted to show it snowing because that was unusual.[1] The film was pitched as Rambo in an office building, referring to the then-successful Rambo film series.[4] Lawrence Gordon and Joel Silver served as the producers. They hired director John McTiernan because of his work with them on the successful 1987 action film Predator.[5][6][7] Before joining, McTiernan wanted to address the film's tone. He said: "My principle concern going into this was that it was a story that concerned terrorists, and terrorist movies are usually mean, filled with all sorts of mean, nasty acts. And I didn’t say yes to this project until we figured out some ways to put, in essence, some joy in it."[3]

Writing

Stuart began working 18-hour days, traveling from his home in Pasadena, California, to his office at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, returning home only briefly to put his children to bed. He became exhausted, which left him feeling on "edge".[1] The situation led to an argument with his wife. Afterward, he went for a drive and accidentally hit a large refrigerator box on the road. It turned out to be empty, but the encounter had triggered a near-death experience for Stuart. He returned home to reconcile with his wife; Stuart wrote 35 pages that night.[1] He had struggled to find a narrative core that could capture the audience's attention, but after his accident, he realized that it should be about a stubborn man trying to reconcile with his wife.[8][1] Stuart used the marital strife and collapse experiences of his peers to shape the McClane's marriage.[1]

John McClane was named John Ford initially, but 20th Century Fox felt this disrespected the deceased director of the same name. Stuart chose McClane as a "good strong Scottish name", based on his own Celtic heritage. He described the character as a flawed hero learning a lesson in the worst possible situation. He becomes a better person by the end, but not a different one.[1] Having no experience writing action films, Stuart drew on his experience writing thrillers with a focus on making the audience care about McClane, Holly and their reconciliation.[1] Levin helped Stuart pitch his story to studio executives, including Gordon. Gordon left the meeting shortly after it had begun, telling Stuart to just go and write the script. Stuart finished his first draft five-and-a-half weeks later.[1]

Stuart credits Levin as instrumental in helping him to understand Nothing Lasts Forever.[1] Many plot points were translated from the novel to the film, including throwing C4 down an elevator shaft and the central character, Joe Leland, leaping from the roof. However, the novel is told entirely from Leland's perspective; events he is not present for are not detailed.[9][1][10] It is also more cynical and nihilistic: Leland visits his drug-addicted daughter at the Klaxon building, and she dies having fallen from the building alongside villain Anton Gruber. Gruber is a terrorist using naive, young male and female guerilla soldiers to rob the building because of Klaxon's support for a dictatorial government. This made their motivations less clear and Leland more conflicted about killing them, especially the women. Leland is written as an experienced older man working as a high-powered security consultant.[10][1][7]

Stuart created new when McClane is not present. This allowed him to expand upon or introduce characters: Powell is given a wife and children, allowing him to relate more closely to McClane so they develop a more in-depth relationship; Argyle—who disappears early in the novel—is present in the script, supporting McClane by broadcasting rap music over the terrorists' radios. The journalist Thornburg is introduced.[1] A fan of prominent Western film actor John Wayne, Stuart was inspired to carry a Western theme throughout the script, including cowboy lingo. He also made friends with a construction superintendent at the under-construction Fox Plaza in Los Angeles, giving him access to the building to gain ideas on how to lay out the characters and scenes. His finished screenplay was delivered on a Friday in June 1987. It was greenlit by Saturday, in part because 20th Century Fox needed a big summer film for 1988.[1]

Casting

Though the main character names differed, because Die Hard was based on the novel sequel to The Detective film, the studio was contractually obligated to offer Frank Sinatra the role. Sinatra, who was 70-years-old at the time, declined.[3][2][7] The role was also offered to stars including: Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Richard Gere, Clint Eastwood, Harrison Ford,[6][11] Burt Reynolds,[12] Nick Nolte, Mel Gibson, Don Johnson, Richard Dean Anderson,[2] and Paul Newman.[13] The prevailing action archetype of the era was a muscle-bound, invincible, macho man like Schwarzenegger, an established star who had helped make McTiernan's Predator a success. Schwarzenegger wanted to move away from action films and into comedy and turned down the role to star in the 1988 comedy Twins.[2] Willis was known mainly for his comedic role as detective David Addison in the romantic comedy television series Moonlighting, starring opposite Cybill Shepherd. Though not the producers' first choice, he declined the role because of his contractual obligations to Moonlighting. However, when Shepherd became pregnant, the show's production was shuttered for eleven weeks, giving Willis enough time to take the role.[2]

McTiernan's then-girlfriend happened to be sitting on a plane next to a representative of CinemaScore. She asked them to provide data analysis to show if Willis could work as the star. The resulting data showed that casting Willis would not have a negative impact; his participation was confirmed two weeks later.[14] The choice was controversial; Willis had only starred in one other film, the moderately successful comedy Blind Date (1987).[2][15] There was also a clear distinction between film and television actors, and though films like Ghostbusters (1984) had demonstrated that television stars could lead a blockbuster film, other TV actors like Shelley Long and Bill Cosby had failed in their recent attempts to make the transition.[16][6] Willis received $5 million for the role, a figure virtually unheard of even for major stars at the time. This defied the Hollywood hierarchy by giving Willis a comparable salary to more successful actors like Dustin Hoffman, Warren Beatty, and Robert Redford.[5]

Then 20th-Century Fox president Leonard Goldberg justified the figure by saying that Die Hard needed an actor of Willis' potential.[5] Gordon said that Willis' everyman persona was essential to conveying that the hero could actually fail.[17] Other Fox sources were reported as saying the studio was desperate for a star after being turned down by so many popular actors.[18] Willis said, "They paid me what they thought I was worth for the film, and for them."[19] He described the character as unlike the larger-than-life characters portrayed by Stallone or Schwarzenegger. He said, "even though he’s a hero, he is just a regular guy. He’s an ordinary guy who’s been thrown into extraordinary circumstances...".[15] Willis drew upon his working-class upbringing in South Jersey for the character, including "that attitude and disrespect for authority, that gallows sense of humour, the reluctant hero".[2]

Rickman was already in his early 40s as he made his screen debut as Hans Gruber. He was cast by Silver, who had seen him perform in a Broadway version of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, playing the villainous Vicomte de Valmont.[20][2] Bedelia was cast at Willis' suggestion. He had seen her in her Golden Globe Award nominated performance in the 1983 biographical film Heart Like a Wheel.[8] Veljohnson also appeared in his first major film role; he was cast at the suggestion of casting director Jackie Burch, with whom he had worked previously. Robert Duvall, Gene Hackman, and Laurence Fishburne were considered for the role.[21][22] Ellis is portrayed by Hart Bochner, who was an acquaintance of Silver. His role was shot in chronological order over three weeks. McTiernan had wanted the character to be suave like actor Cary Grant, but Bochner conceived of the character's motivations coming from cocaine use and insecurity. McTiernan hated the performance initially until he noticed Gordon and Silver were entertained by Bochner's antics.[23]

Re-write

Screenwriter Steven E. de Souza rewrote Stuart's script, as he had prior experience in blending action and comedy.[24] He approached the story from the view that Gruber is the protagonist. He said, "If [Gruber] had not planned the robbery and put it together, [McClane] would have just gone to the party and reconciled or not with his wife. You should sometimes think about looking at your movie through the point of view of the villain who is really driving the narrative."[9] De Souza used blueprints of Fox Plaza to help him lay out the story and character locations within the building.[24]

The script continued to undergo changes up to and during filming. Several subplots and character beats were created because during early filming Willis was still working simultaneously on Moonlighting. He would film the show for up to ten hours and then work on Die Hard at night. As this situation was expected to continue for at least a further week, McTiernan opted to give Willis time off to rest and tasked De Souza with adding new scenes they could film in the interim. These included scenes with Holly's housekeeper, an introductory scene for Thornburg, and more moments between Powell and his fellow officers. The scene where Holly confronts Gruber in the wake of Takagi's death was also added during this time.[24]

Silver wanted a scene between McClane and Gruber before the film's denouement. De Souza could not think of an idea that would allow the pair to meet without one killing the other. Between takes, De Souza heard Rickman affecting an American accent to a crew member; he realized that an accent would let Gruber disguise himself when he met McClane. McTiernan discounted the idea as McClane would see Gruber's face while observing him murder Takagi. That scene had not yet been filmed, and it was reworked to conceal Gruber's identity from McClane. With the addition of the Gruber/McClane meeting scene, a different scene in which McClane kills Theo was excised.[24]

In Stuart's original script, Die Hard took place over three days. McTiernan was inspired to have it take place over a single night by Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. He did not want to use terrorists as the villains, as he considered them to be "too mean". McTiernan avoided focusing on the terrorists' politics in favor of making them thieves driven by monetary pursuits; he felt this would make it more suitable summer entertainment.[25]

McClane's character was not fully realized until almost halfway through production. McTiernan and Willis had determined that McClane is a man who does not like himself much but is doing the best he can in a bad situation.[25] McClane's catchphrase, "Yipee-ki-yay, motherfucker", was inspired by old cowboy lingo to emphasize his all-American character. There was a debate over whether to use "Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker" or "yippee-ti-yay, motherfucker".[2] De Souza wrote the catchphrase based on cowboy actor Roy Rogers' own "Yippee-ki-yah, kids".[9]

Filming

Principal photography began in November 1987.[2][26] The budget was reported to be between $25 and $35 million.[27][28][15] Filming took place almost entirely in and around Fox Plaza in Century City, situated on the Avenue of the Stars.[7][29][30] The location was decided upon late into production by production designer Jackson De Govia.[25] A building was needed that was both available and mostly unoccupied. The under construction Fox Plaza offered both; only four or five stories were occupied at the time.[29] Extensive negotiations secured the building for filming with two main conditions: no filming during the day and no damage from explosions.[7]

Cinematographer Jan de Bont said the building's design was distinct, making it a character on its own. Clear views of the building were available from a distance, enabling establishing shots as McClane approaches it. Because Die Hard was filmed on location, the surrounding city could be seen from within the building, enhancing the realism.[29] De Bont frequently used handheld cameras to film closer to the characters, creating a more cinematic "intimacy". Very little of the film was storyboarded beforehand. De Bont said that intricate storyboarding made his job redundant. Instead, he and McTiernan would discuss that day's filming in detail, and the feeling or sensation they wanted to portray. De Bont was more concerned with creating a dramatic rather than an attractive shot; he cited the use of real flares in the film that generated unpredictable smoke and sometimes obscured the image.[29]

Willis's first day on set was on November 2, 1987. He came straight from filming Moonlighting to shoot one of his most pivotal scenes, where McClane leaps from a rooftop as it explodes behind him, saved only by a length of hosepipe.[2] Willis found acting in Die Hard different from previous experiences. He was used to acting against another actor, but in Die Hard he is alone in many of his scenes, talking to himself or others via radio.[19] He did not spend much time with the rest of the cast between takes, opting to spend it with his new partner, Demi Moore. In contrast to their on-screen dynamics, Bedelia and Veljohnson spent most of their time between scenes with Rickman.[31][32]

The film's ending had not been finalized when filming began. In the finished film, Theo retrieves an ambulance from the truck the terrorists arrived in to use as an escape vehicle. As this was a late decision, the truck the terrorists are shown arriving in was too small to hold an ambulance. An additional scene, showing the terrorists synchronizing their TAG Heuer watches, also showed the truck was empty; this scene had to be deleted. This led to other necessary changes. As scripted, McClane realizes that the American hostage he encounters is Gruber because of the distinctive TAG Heuer watch he had seen on the other terrorists; the watches were no longer an established plot point.[33][25] However, it necessitated the introduction of a heroic scene for Argyle, who gets to stop Theo's escape. De'voreaux actually punched Gilyard during the scene, which was added in only in the last 10 days of filming.[24][32] There was flexibility with some roles. Depending on the actors' performances, some characters were kept in the film longer and others killed off sooner.[24] The actors were given some room to improvise, like Theo's line, "The quarterback is toast", Bochner's "Hans, bubby, I'm your white knight", and the henchman Uli stealing a chocolate bar during the SWAT assault.[32][23]

During filming, McTiernan, De Bont, and first assistant director Benjamin Rosenberg became trapped in an elevator. After 30 minutes, a team of stuntmen arrived to help them escape via the roof hatch and crossover to another elevator parked next to it.[34] McTiernan took stylistic influence from French New Wave cinema when editing the film. He recruited Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link to edit scenes together while in mid-motion. This was contrary to the mainstream style of editing used at the time.[35] The film's final cut runs for 132 minutes.[36]

Music

Before hiring composer Michael Kamen, McTiernan knew one musical piece he wanted to include—Beethoven's 9th Symphony (commonly known as "Ode to Joy"), having heard it in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971).[37] Kamen objected to using the piece in an action film. He offered to misuse German composer Richard Wagner's music instead of tarnishing that of Beethoven.[38][37] Once McTiernan explained how the 9th Symphony had been used in A Clockwork Orange to highlight the ultra-violence, Kamen had a better understanding of McTiernan's intentions.[37] In exchange, Kamen insisted that they also license the use of "Singin' in the Rain" (1952) (also used in A Clockwork Orange) and "Winter Wonderland" (1934).[37][38] He mixed the melodies of "Ode to Joy", "Winter Wonderland", and "Singing in the Rain" into his score, mainly to underscore the villains.[38][37][35] The samples of "Ode to Joy" are played in slightly lower keys to sound more menacing; the references build to a full performance of the song when Gruber finally accesses the Nakatomi vault.[39] The score also references "Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!".[40][41]

When Kamen first saw Die Hard, it was largely incomplete and he was unimpressed.[38] He saw the film as primarily about this "phenomenal bad guy" who made McClane seem less important.[38] Kamen was dismissive of film scores, believing they could not stand alone from the film. Even so, he admitted there were tracks from his Die Hard score that he liked.[42] His original score incorporates pizzicato and arco strings, brass, woodwinds and sleigh bells added during moments of menace to counter their festive meaning.[43][41] There are other classical diegetic songs in the film; the musicians at the party play Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 by Johann Sebastian Bach.[43]

McTiernan did not like a Kamen piece created for the final scene where Karl emerges from the building to kill McClane. He decided to use a temporary track that was already in place; a piece of unused score from composer James Horner's work for Aliens (1986); cues are also used from the 1987 action film Man on Fire.[25][40] Like Aliens, Kamen's score was edited significantly, with music samples looped over and over and cues added to scenes.[40] The film features "Christmas in Hollis" by Run-DMC. It would go on to be considered a Christmas classic, in part because of its use in the film.[44]

Stunts and designs

Stunts

The perception of film stunts had changed shortly before production of Die Hard began following an accident on the set of the Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983) that had killed several actors. A push was made to prioritize a film's crew over the value of the film itself.[34] Even so, Willis insisted on performing many of his own stunts, including rolling down steps, making tall leaps, and being positioned on top of an active elevator.[29][2] Willis suffered a permanent two-thirds hearing loss in his left ear from his stunt work for the film.[45] The first scene he shot was his leap from the top of Nakatomi Plaza with a firehose wrapped around his waist. The stunt involved a 25-foot leap from a five-story parking garage ledge onto an airbag as a 60-foot wall of flame exploded behind him; he considered it to be one of his toughest stunts.[15][2] Willis was coated in fire-retardant liquid to protect him from the flames. The explosive force pushed him towards the edge of the airbag; the crew was concerned he had died.[2] Stuntman Ken Bates stood in for Willis when his character is hanging from the building.[46]

A set was used for the following scene where McClane shoots out a window to re-enter the building. It was shot approximately halfway into the filming schedule so that all involved had gained more stunt experience. The window was made of fragile sugar glass that took two hours to set up; there were only a few takes for this reason. A team of stuntmen positioned below the window dragged the hosepipe and pulled Willis towards the edge. Stuntmen were preferred over a hoist, as they could better control Willis' fall if he went over the edge.[34] The scene where McClane falls down a ventilation shaft and catches onto a lower opening was the result of Willis' stuntman accidentally falling further than intended. Frank Urioste kept the scene when he worked on the editing.[25]

For Gruber's fall from Nakatomi Plaza, Rickman was dropped between 20 feet (6.1 m) and 70 feet (21 m); reports are inconsistent.[25][29][47] He was suspended on a raised platform and then dropped onto a blue screen airbag.[25][47] This allowed the background behind him to be composited on an optical printer with footage from Fox Plaza, and footage of cannon-shot confetti that looked like falling bearer-bonds. Rickman had to fall backward onto the bag, something even stuntmen avoid to control their fall.[47] Even so, McTiernan convinced Rickman by demonstrating the stunt himself and falling onto a pile of cardboard boxes.[34] Rickman was told he would be dropped on a count of three. He was let go early to elicit a genuine look of surprise. McTiernan said, "there's no way he could fake that".[25][34] The first take was used, but McTiernan convinced Rickman to perform a second one as backup.[47]

Capturing the stunt was difficult. Rickman was dropped at a rate of 32 feet (9.8 m) per second, and it was impossible for a human operator to refocus the camera manually quickly enough to prevent the image from blurring as he fell away.[34] Supervised by visual effects producer Richard Edlund, Boss Film Studios engineered an automated system that could relay information from an encoder on the camera to a computer that would instantly calculate the necessary change in focus and operate a motor on the camera's focus ring to make the change.[47] A wide-lense camera shooting at 270 frames per second was used, creating footage that played 10 times slower than normal. Despite these innovations, the camera struggled to keep Rickman entirely in focus during his 1.5 second fall; the scene cuts away from Rickman as the usable footage runs out.[34] A stuntman in a slow-fall rig was lowered from Fox Plaza to complete Gruber's fatal descent.[47]

Months of negotiations took place before permission was given to drive a SWAT vehicle up the steps of Fox Plaza as the script required. A railing knocked over during shooting was never replaced.[25][30] The vehicle was detonated during the scene, although the terrorist rockets were small explosives moving along a guide wire. In the scene where McClane throws C4 down the elevator shaft to stop the assault, the effects team blew out every window on one floor or the building; they were unsure what was going to happen until they did the stunt.[29] The final helicopter scene took six months of preparation, and only two hours were set aside to film it. It took three attempts above Fox Plaza, and nine camera crews filming with 24 different cameras.[25][29] De Bont said the different angles enhanced the on-location realism.[29] Only crew were allowed within 500 feet (150 m) of the flight path.[25]

Mortar-like devices filled with propane were used for explosions. They took ten minutes to install and offered a six-second burst of flame.[34] The only miniature effect used is a recreation of the Nakatomi rooftop that is destroyed.[29] McTiernan employed the weapons specialists from Predator to pick the guns used in the film.[34] Because Buhringer (Fritz) was an inexperienced actor and filming was behind schedule, an American Indian stuntman was put in a blond wig and equipped with squibs to capture the character's death in one take.[32]

Design

To prevent the in-building locations looking similar because of the standard fluorescent office lighting, De Bont concealed small film lights in high locations. He controlled these to create more dynamic and dramatic lighting. He placed fluorescent tubes on the floor in one scene to indicate they had not been installed; this gave him the opportunity to use unusual light positioning.[29] The shifting nature of the filming script meant some sets were designed before it was known what they were to be used for.[25]

The Nakatomi Building's 30th floor—where the hostages are held—was one of the few sets.[24][25] It contained a recreation of the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house Fallingwater, including a large rock with water dripping from it. De Govia's reasoning was that it reflected the trend at the time of Japanese corporations buying up American corporate assets. Fallingwater had been purchased and reassembled it in their own building. An early design for the Nakatomi logo was too reminiscent of a swastika; the final design is closer to a Samurai warrior's helmet. A 380-foot-long matte painting provided the city backdrop as viewed from inside the building's 30th floor. It featured animated lights and other lighting techniques to present both moving traffic, daytime and nighttime.[25]

Release

The summer of 1988 was expected to be dominated by action and comedy films,[28] however, a broader range of films were released that year. More films targeted older audiences rather than teenagers, a reflection of the increasing age of the average audience member.[48] Sequels to financially successful films, Crocodile Dundee II and Rambo III, were expected to dominate the May box office and break opening weekend revenue records. Their collective potential was significant enough for George Lucas—who had dominated May in previous years with Star Wars and Indiana Jones films—to move his film Willow to avoid the competition. Industry executives also had high expectations for the romantic comedy Coming to America and the fantasy comedy Who Framed Roger Rabbit.[28]

However, expectations for Die Hard were low compared to its action film competition—the Schwarzenegger-starring Red Heat and Clint Eastwood's The Dead Pool. The New York Times noted that Die Hard, and the comedies Big Top Pee-wee and Bull Durham, would be closely scrutinized by the industry for success or failure. Die Hard was singled out for Willis' salary, and the failure earlier that year of the western Sunset, his previous film, which brought into question his capability as a leading man.[28] Lawrence Gordon agreed that by not using a major action star like Stallone or Eastwood, audience interest in Die Hard was lower than it might have been. The larger salaries paid to these stars were based on the built-in audience they could attract to a film's opening week, with good word of mouth supporting the film thereafter. Willis did not have a built-in audience.[17]

Marketing

Willis featured prominently in the film's early marketing campaign, but it underwent several changes as the film's release date drew nearer.[49][11][17] At the time, Willis had developed a reputation as an "arrogant" actor concerned with his own fame. His refusal to address this, or speak about his personal life to the media, had reinforced this perception. For his part, Willis said that he wanted the media to focus on his acting.[19] There were reports that cinema audiences would moan at Willis' appearance in the Die Hard trailers. A representative from an unnamed theater chain pulled the trailer in response.[49] Research by several film studios revealed that audiences had a negative opinion of Willis overall and little or no interest in seeing him in Die Hard.[17] Newsweek's David Ansen called Willis "the most unpopular actor ever to get $5 million for making a movie".[6]

As 20th Century Fox's confidence in Willis' appeal faltered, the film's posters were changed to focus entirely on Nakatomi Plaza, with Willis' name receiving billing in tiny print.[11][49] Willis' image was not included in the film's first full-page newspaper advertisement in mid-July.[17] 20th-Century Fox's domestic distribution and marketing president, Tom Sherak, denied that Willis was being hidden, saying their marketing strategy had changed when they realized that the building was as important a character as the actor.[49] Defying expectations, sneak previews of the film were well received by audiences.[17] The week following its release, the advertising was changed to feature Willis more prominently.[17] Despite his dislike of interviews, Willis appeared on several daytime shows to promote the film. Explaining why he was more involved in the promotion for Die Hard, Willis said, "I'm so excited about this film... To me, it represents why I wanted to be an actor."[19][49]

Box office

Die Hard's premiere took place on July 12, 1988, at the AVCO theater in Los Angeles, California.[50] In North America, the film received a limited release in 21 theaters on July 15, 1988, earning $601,851—an average of $28,659 per theater. It was considered a successful debut with a high per-theater average gross.[51] The Los Angeles Times said that the late change in advertising focus and diminishing popularity for action films should have worked against Die Hard. Instead, positive reviews and the limited release had made it a "must-see" film.[52]

It received a wide release the following week on July 22, 1988, across 1,276 theaters. The film earned $7.1 million—an average of $5,569 per theater. The film finished as the number three film of the weekend, behind Coming to America ($8.8 million)—in its fourth week of release—and Who Framed Roger Rabbit ($8.9 million), in its fifth.[53] The film fell to number four in its third week with a further gross of $6.1 million, just behind Coming to America ($6.4 million), Who Framed Roger Rabbit ($6.5 million) and the debuting romantic comedy Cocktail ($11.7 million).[54] In its fourth weekend, it rebounded to the number three position with $5.7 million.[55] While the film never claimed the number one box office ranking, it spent ten straight weeks among the top five-highest-grossing films.[55][6] In total, the film earned an approximate box office gross of between $81.3 million and $83 million.[56][57] This made it the seventh-highest grossing film of 1988, behind Crocodile Dundee II ($109.3 million), buddy comedy Twins ($111.9 million), fantasy comedy Big ($114.9 million), Coming to America ($128.1 million), Who Framed Roger Rabbit ($154.1 million) and comedy-drama Rain Man ($172.8 million).[58]

Outside North America, Die Hard is estimated to have earned $57.7 million, giving it an approximate cumulative gross of between $139.1 million and $140.7 million.[56][57] This figure makes it the tenth-highest-grossing film worldwide of 1988 behind Big ($151 million), Cocktail ($171 million), A Fish Called Wanda ($177 million), Rambo III ($189 million), Twins ($216 million), Crocodile Dundee II ($239 million), Coming to America ($288 million), Who Framed Roger Rabbit ($329 million) and Rain Man ($354 million).[lower-alpha 1]

Reception

Critical response

Die Hard received mixed reviews on its release.[61] Dave Kehr said that the film was inspired by films like Alien (1979) and Robocop (1987), creating an "elegant", humorous and sentimental design. Though the "perfection of the form" it lacked a personality of its own.[62] Caryn James called it "excessive", drawing on every possible action genre trope, though the film makes it work as "exceedingly stupid, but escapist fun".[63] Kevin Thomas criticized it for being highly calculated, designed to sacrifice quality in exchange for reaching the widest possible audience base, citing plot holes and a lack of credibility. He said that it held potential as an intelligent thriller, but instead became an ever-increasing depiction of increasingly "numbing" violence and carnage.[64]

Vincent Canby said it would appeal to audiences who require a constant stream of explosions and loud noises, calling it the "perfect movie for our time". He described it as an intense but fleeting experience akin to "snorting pure oxygen".[65] Hal Hinson called it "relentlessly" thrilling, but no fun to watch.[66] Richard Schickel said that the action genre had no future if it just continued to offer bigger and better explosions and noise.[67] Howe was more positive, calling it a "firepowered, blood-drenched action picture".[68] Thomas called it cynical and criticized the story for undermining the humanity and warmth behind McClane's and Powell's friendship, by having Powell's redemption for shooting a child come from violently shooting Karl.[64] Hinson felt the audience is manipulated into cheering for the act.[66]

Critics were conflicted over Willis' performance.[66][62][68] Desson Howe said that it elevated the film to the level of action films like Beverly Hills Cop (1985) and Lethal Weapon.[68] Thomas agreed that Willis's turn made him a credible star, and demonstrated his comedic range.[64] Hal Hinson said that Willis gave a star performance, but his dramatic acting fell flat. He continued that Willis' "grace and physical bravado" allowed him to stand alongside the likes of Stallone and Schwarzenegger, but that his biggest strength—his comedic ability—is not used enough.[66] Variety agreed, saying that Willis is at his best when being funny, as his acting suffers towards the film's end.[69] Canby criticized Willis for lacking "toughness",[65] and Kehr said that he still came across as a TV rather than film star.[62] Schickel said Willis' performance was "whiny and self involved", and that removing his undershirt by the film's denouement was the totality of his acting range. Though he acknowledged it would be difficult to perform when acting only against special effects.[67]

Rickman's performance was mainly praised.[66][62] James said that he was the film's best feature, portraying "the perfect snake",[63] and Hinson compared his work to the "sneering", malevolent performance by Laurence Olivier in Richard III (1955).[66] Kehr called Gruber a classic villain, one who combines the silliness of actor Claude Rains and the "smiling dementia" of actor George Macready.[62] Vincent Canby said that Rickman provides the only credible performance, and Roger Ebert—who was otherwise critical of the film—singled out Rickman's performance for praise.[70] Variety agreed that Rickman's performance was good, but that he occasionally acted "over the top".[69] Hinson criticized the film for not utilizing Bedelia's talents, as McClane's relationship with Powell is given more prominence.[66] Schickel said that having McClane confess his sins to Powell just before rescuing his wife, robbed their marital reunion of meaning.[67] They both felt that only McClane's and Powell's characters are developed.[66][67] The villains were criticized for lacking humanity and McClane's allies—except Powell-were described as incompetent.[67] Ebert focused his criticism on the police captain (portrayed by Gleason). He cited the character as an example of a "wilfully useless and dumb" obstruction that wasted screen time and derailed the film from being as tightly plotted as it needed to be to be a successful thriller.[70] Thomas commended the casting of several minority actors.[64]

McTiernan's direction was frequently praised.[64][62][65] Kehr said his "logical" direction granted the film a sense of scale more significant than its content.[62] Thomas said that the scene of the terrorists' takeover of the building was a "textbook study" and provides a strong introduction to both the director and De Bont's cinematography.[64] He felt De Govia's set design was "ingenious" and Kehr noted the design lent itself to the building becoming its own character.[62] Ebert said the film offered both "impressive stunt work" and "superior special effects."[70]

Audiences reacted positively; CinemaScore polls reported that audiences gave an average rating of "A+" on a scale of A+ to F.[71] It was one of several films that year labelled "morally objectionable" by the Roman Catholic Church, along with the religious drama The Last Temptation of Christ, Bull Durham and A Fish Called Wanda.[72] Robert Davi first saw the finished film with Schwarzenegger, who reacted positively to it. However, he did not like Davi's character's narrative saying, "You were heroic! And now you’ve turned into an idiot! I can’t believe it here!"[32]

Accolades

At the 1989 Academy Awards, Die Hard received four nominations: Best Film Editing for Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link; Best Visual Effects for Richard Edlund, Al DiSarro, Brent Boates and Thaine Morris; Best Sound Effects Editing for Stephen Hunter Flick and Richard Shorr (all three awards were won by Who Framed Roger Rabbit); and Best Sound for Don J. Bassman, Kevin F. Cleary, Richard Overton and Al Overton Jr. (losing to the biographical film Bird).[73] That same year, Michael Kamen won a BMI TV/Film Music Award for his work on the film's score.[74]

Post-release

Aftermath and performance analysis

The summer of 1988 saw box office grosses totaling $1.7 billion, breaking the previous year's record-breaking summer by $100 million.[48] 1988 was also the most successful summer since 1984 when only three films earned more than $100 million in North America—Ghostbusters, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, and Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.[75] Die Hard was considered an enormous success, defying pre-release expectations to earn approximately $140 million on a $25–$30 million budget.[2][75] The film was seen as an anomaly among the action films released that year, which was otherwise dominated by comedy films. Other action films had failed to meet expectations; Rambo III and Red Heat—which had been predicted to perform well—were seen as underperforming disappointments.[76][4] In late 1988, Sheila Benson wrote that the failure of films like Rambo III and the success of those like Die Hard demonstrated a generational shift in the types of people making up audiences and their tastes. In particular, 25 to 37-year-old males whose attitudes towards film content had turned against alcohol abuse, sexism and mindless machismo.[77]

Along with films like Big and Young Guns, Die Hard was credited with revitalizing 20th Century Fox, which had had few successes in the recent preceding years. It also showed the action genre was not "dead".[48] It raised Willis from TV stardom to worldwide recognition and brought fame to Rickman.[2] Willis' $5 million salary was seen as the peak of the 1980s bidding wars between new and old managers vying for jobs. The New York Times described it as the salary equivalent of an "earthquake". Then-MGM/UA chairman Alan Ladd Jr. said that it threw "the business out of whack" adding "like everybody else in town, I was stunned". It was seen as the most substantial change to salaries since Dustin Hoffman was paid $5.5 million to star in Tootsie (1982) at a time when top salaries ranged from $2 million–$3 million. It was expected that salaries for major stars would increase significantly, to ensure they were paid more than a newer star like Willis.[5][78] McTiernan transitioned his success into directing a project based on one of his favorite works The Hunt for Red October (1990).[79] Veljohnson's performance resulted in his casting in the 1989–1997 sitcom Family Matters.[21]

Home media

Die Hard was released on VHS in January 1989. The film could be purchased outright for $89.98, but it performed better as a rental.[80] It debuted as the number three film on the early February rental charts, rising to number one the following week.[81][82][83] It spent six of its first seven weeks in release at number one until it was replaced by A Fish Called Wanda at the end of March.[84][85] By 1997, the film was estimated to have earned $36 million from rentals.[86]

The earliest known release of Die Hard on DVD was in late 1999 as a collection with its sequels Die Hard 2 (1989) and Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995).[87][88] A special 5-Star Edition DVD was released in 2001 including commentary by McTiernan, De Govia, and Edlund, and deleted scenes, trailers and behind-the-scenes images.[89][90] It received a Blu-ray disc release in 2007. This version includes the extra features of the 5-Star edition.[91][92] Die Hard: The Nakatomi Plaza Collection was released in 2015, collecting all five films on a Blu-ray disc in a container shaped like Nakatomi Plaza.[93] For its 30th anniversary in 2018, the film was released in a remastered 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray; the set also includes a standard Blu-ray and digital download. A limited-edition steel-book case version was also released.[94]

Thematic analysis

Die Hard can be thought of as a story about obtaining redemption through violence. McClane comes to Los Angeles to save his marriage, but immediately makes the same mistakes that drove his wife, Holly, away. It is only after he defeats the terrorists, often using extreme violence, that McClane is able to reconcile with his wife.[95][7] Similarly, Powell is haunted by his mistaken shooting of a child and has been unable to use his police gun since the tragedy. He finds redemption by drawing his gun and shooting Karl to save his friend McClane.[95] Several male characters who are driven by rage or ego suffer for it including the FBI agents, Karl or Ellis and even McClane who nearly loses Holly by showing off after shooting Gruber. The more even-tempered characters—often African American—fare better: Powell who supports McClane, Argyle whose heroic moment is stopping Theo's escape and Theo, who survives the events.[4] McClane identifies himself as a Roman Catholic, a religion that requires penance to earn redemption. He is forced to endure physical punishment, including his feet being cut by shards of glass, a "stigmata" that causes him to leave a trail of blood behind him. In making these sacrifices, he salvages his family. In this sense, McClane can be seen as a modern, working class Christ-like figure.[95]

In Willis' own view, if given the choice, McClane would pass the responsibility of dealing with the terrorists on to anyone else, but he is forced to serve as a reluctant hero.[2] When the character is introduced, he is wearing his wedding ring. This serves as a symbol of his commitment to his marriage. When viewers are introduced to Holly, she is the opposite; she has returned to using her maiden name and is not wearing her wedding ring. Instead, she is gifted a Rolex watch by her employers, serving as both a symbol of her commitment to her job and the division between she and her husband. When McClane unclasps the watch at the film's end to free Holly from Gruber's grasp, the totem of their separation is broken, and they appear to have reconciled.[96]

Die Hard has elements that are anti-government, anti-bureaucracy and anti-corporation.[7][95][3] A terrorist asserts that McClane cannot harm him because there are rules for policemen, rules he is aware of and intends to exploit. McClane responds "so my captain keeps telling me", suggesting that he operates outside of bureaucratically approved procedures.[95][3] The police often present a bigger obstacle than the terrorists. They repeatedly try to deter McClane from interfering and let them handle events, unaware that the terrorists have already anticipated their every action.[95] The police chief is portrayed as incompetent, and the FBI is shown to be ruthless and uncaring, indifferent to the lives of the hostages as long as they kill the terrorists.[97][95] McClane is an everyman fighting against terrorists who are dressed like elite big-city workers, while being hampered by people outside who are not risking their lives, including the police, the FBI, and an intrusive journalist. Each is punished for standing in McClane's way.[7]

The film can also be seen as xenophobic. Alongside the mainly German group of terrorists, Nakatomi Plaza is owned by a Japanese corporation; at the time Japanese technology firms threatened to dominate the American technology industry.[95] The hostages who need saving are American.[43] When McClane prevails, the building remains Japanese property, but the inference is that American ingenuity will prevail.[43] Germany and Japan are America's enemies and are portrayed as having forsaken their integrity in the pursuit of financial gain.[65] David Kehr said the film embodies a resentful 1980s "blue-collar rage" against feminists, Yuppies, the media, the authorities and foreign nationals.[62] Even so, it can be seen as a progressive piece—African American actors like Veljohnson, Gilyard, and White are featured in prominent and important roles.[95]

The A.V. Club noted that unlike many other 1980s films, Die Hard does not contain any allusions to the Vietnam war. The film mocks the idea when one FBI agent remarks that their helicopter assault is reminiscent of the war in Saigon; his partner responds that at the time he was only in middle school.[98] Conversely, Empire felt the film does reference Vietnam by showcasing an ill-equiped local taking on highly equipped foreign invaders; this time America wins.[7] McClane is an all-American stereotype. Several comparisons are made between him and Western cowboy stars like Roy Rogers, John Wayne and Gary Cooper.[7][95] Gruber is the opposite, a classically educated, European villain who refers to America as a "bankrupt" culture.[95]

Legacy

Die Hard is now considered one of the greatest action films ever made. It was also massively influential on filmmaking.[7][98] It redefined the action film genre. Before its release, action films often starred muscle-bound men like Schwarzenegger and Stallone, who portrayed invincible, infallible, catchphrase-spouting heroes in unrealistic settings. Willis's portrayal of John McClane ran completely counter to that archetype. McClane was a normal person with an average physique. He was failing, both personally and professionally. He serves as a vulnerable, identifiable hero who openly sobs and admits his fear of death and sustains lasting damage. Importantly, his one-liners do not come from a place of superiority over his foes, but as a nervous reaction to the extreme situation in which he finds himself, which he is only able to overcome through enduring suffering and using his own initiative.[2][98][7][10][7][10]

Similarly, Rickman's portrayal of Gruber redefined action villains who had previously been bland figures or eccentric madmen. Gruber ushered in the clever nemesis; he is an educated, intelligent villain, who serves as the antithesis of the hero.[7] He has been referred to as one of the most iconic villains in the genre.[98] Empire magazine called Gruber one of the finest villains since Darth Vader. Rickman described the role as a "huge event" in his life.[7] Though other more typical 1980s-style action films were released, the genre gradually shifted to a focus on smaller, more confined settings, everyman heroes and charming villains with competent plans.[98]

In the years since its release, Fox Plaza has become a popular tourist attraction, although the building itself cannot be toured.[30] One of the floors used for filming later became the office of United States President Ronald Reagan. When his head of staff toured the still-under-construction area, it was littered with broken glass and bullet casings.[99] A giant mural depicting McClane's crawl through a Nakatomi Plaza vent was erected at the Fox Studio lot in Century City to celebrate the film's 25th anniversary in 2013.[100]

Cultural impact

In 2017, Die Hard was selected by the United States Library of Congress to be preserved in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[101][102] In July 2007, Bruce Willis donated the undershirt worn in the film to the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution.[103] The blood and sweat stained vest is considered iconic, an emblem of McClane's difference from archetypal, invincible heroes.[2]

One of the most influential films of the 1980s, Die Hard served as the blueprint for action films that came after, especially throughout the 1990s.[96] The term "Die Hard on/in a..." has become shorthand to describe a lone, everyman hero who must overcome an overwhelming opposing force in a relatively small and confined location.[96][2] Examples include: Under Siege (1992, "Die Hard on a battleship"); Passenger 57, Executive Decision and Air Force One (1992, 1995, and 1997 respectively, "Die Hard on a plane"); Cliffhanger (1993, "Die Hard on a mountain); Speed (1994, "Die Hard on a bus"); Sudden Death (1995, "Die Hard in a stadium); and Con Air (1997, "Die Hard on a prison plane).[96][2][98] Willis himself recalled once being pitched a film that was "Die Hard in a skyscraper". He said he was sure it had already been done.[2] It was not until the 1996 action-thriller film The Rock ("Die Hard on Alcatraz Island"), that the tone of action films changed significantly, and films like The Matrix (1999), which emphasized the use of CGI effects, made the practical effects in films like Die Hard feel more dated. Writing for The Guardian in 2018, Scott Tobias observed that none of these later films readily captured the complete effectiveness of the Die Hard story.[96]

The film has been a source of inspiration for filmmakers including: Lexi Alexander, Darren Aronofsky, Joe Carnahan, Gareth Evans, Barry Jenkins, Joe Lynch, Paul Scheer, Brian Taylor, Dan Trachtenberg, Colin Trevorrow and Paul W. S. Anderson.[104][105] During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, it was among the action films director James Gunn recommended people watch.[106] The film's popularity has seen it referenced across a wide variety of media, including TV shows, films; video games; and music. It has even been referenced in films and television targeted at children.[100] Willis reprised his role as McClane in the 1993 parody film Loaded Weapon 1.[107]

There has been much debate over whether Die Hard is a Christmas film. Those in favor argue that its Christmas setting is sufficient to qualify it as a Christmas film. Those opposed argue that it is an action film whose events just happens to take place at Christmas.[108][109] Only one-quarter of Americans polled consider it to be a Christmas film. A 2017 YouGov poll of over 5,000 UK citizens determined that only 31% believed that Die Hard is a Christmas film; those who did skewed under the age of 24, while those opposed were mainly over 50.[110][111] De Souza and Stuart support it being a Christmas film, while Willis feels it is not.[13][112][113][114] On the film's 30th-anniversary in 2018, 20th Century Fox stated that it was "the greatest Christmas story ever told". They released a re-edited trailer for the film, portraying it as a traditional Christmas film. According to De Souza, Silver predicted the film would be played at Christmastime for years.[114][115][116]

In 2015, readers of Rolling Stone ranked it the number 10 action film of all time;[117] readers of Empire voted it number 20 in 2017.[118]

Contemporary reception

Die Hard is considered one of the greatest action films ever made.[119][120][121] A retrospective review by The A.V. Club said that Willis' everyman persona is key to the film's success.[98] Rickman said he believed it had continued to find fans decades after its release because it was delivered with wit and style.[2] It is listed in the film reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, which says:

Before Die Hard, Bruce Willis was just an actor with one hit TV show (Moonlighting) and a flop movie (Blind Date [1987]) to his name, but following Die Hard's huge success, he deservedly became one of Hollywood's hottest stars. His cocky charm breathes life into the character of John McClane... McTiernan packs his skyscraper adventure with explosions, fights, and relentless action... along with writers Jeb Stuart and Steve DeSouza... effectively redefines the action movie as one-man-army. Willis quips his way through a series of clever setups and payoffs... Superbly acted by Willis as a guy who really would rather be somewhere else, McClane is a hero for the 1990s... A true rollercoaster ride of a movie. [122]

In 2001, the American Film Institute (AFI) ranked Die Hard number 39 on its 100 Years... 100 Thrills list recognizing the most "heart-pounding" films.[123] In 2008, Empire ranked it number 29 on its list of the 500 Greatest Movies of all Time.[119] In 2014, The Hollywood Reporter's entertainment industry-voted ranking named it the eighty-third best film of all time.[124] The film's characters have also been recognized. In 2003, the AFI ranked Hans Gruber number 46 on its 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains list.[125] In 2006, Empire ranked McClane number 12 on its list of the 100 Greatest Movie Characters; Gruber followed at number 17.[20][126]

Several publications have listed it as one of the greatest action films of all time, including: number one by Empire,[127] IGN[120] and Entertainment Weekly;[121] number 10 by Timeout;[128] number 14 by The Guardian;[129] number 18 by Men's Health[130] and unranked by Complex,[131] Esquire[132] and The Standard.[133] The British Film Institute called it one of the greatest 10 action films of all time, saying it is the "quintessential 80s action flick.[134] Adding to the debate over Die Hard's status as a Christmas film, it has appeared on several lists of the top holiday films, including at: number one by Empire,[135] Forbes,[136] and San Francisco Gate;[137] number four by Entertainment Weekly[138] and The Hollywood Reporter;[139] number five by Digital Spy;[140] and number eight by The Guardian.[141]

Contemporary review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes offers a 93% approval rating from the aggregated reviews of 76 critics, with an average rating of 8.53/10. The consensus reads, "Its many imitators (and sequels) have never come close to matching the taut thrills of the definitive holiday action classic."[142] The film also has a score of 72 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 14 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[143]

Merchandise

The enduring popularity of Die Hard led to a wide variety of merchandise produced for fans including: clothing; Funko Pops; coloring and activity books; crockery; and Christmas jumpers, ornaments, and an illustrated Christmas book retelling the film.[144] There have been several video game adaptations of the film. A third-person shooter, Die Hard, was released in 1989 for the Commodore 64 and Microsoft Windows. Different top-down shooter versions were released for the TurboGrafx-16 and the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). The TurboGrafx-16 edition begins with McClane fighting terrorists in a jungle; the NES version offers a "foot meter" that slows McClane's movements after he repeatedly steps on shattered glass.[145][146]

Die Hard Trilogy (1996), a popular title for the PlayStation, adapted Die Hard and its then-two sequels.[147][148] In 1997, existing Japanese arcade game Dynamite Deka was redesigned and released in western territories as Die Hard Arcade. Players choose either McClane—or secondary character Chris Thompsen—to battle through Nakatomi Plaza, defeat terrorists led by White Fang, and rescue the President's daughter.[145][149] Two first-person shooters were released in 2002: Die Hard: Nakatomi Plaza, which recreates the events of Die Hard and Die Hard: Vendetta, which serves as a narrative sequel to the film, pitting McClane against Gruber's son Piet.[147][145][149]

Die Hard: The Ultimate Visual History—a book chronicling the development of the Die Hard film series—was released in 2018 to coincide with the film's 30th anniversary.[150] A board game based on the film was released in 2019. Developed by USAopoly, Die Hard: The Nakatomi Heist casts up to four players as McClane, Gruber, and his terrorists, each vying to complete their opposing tasks.[151][152]

Sequels

.jpg)

The success of Die Hard spawned four film sequels.[98] Die Hard 2 was rushed into production to capitalize on the original's popularity. It's budget was $70 million and grossed $240.2 million at the box office.[153] Stuart and McTiernan did not return for the film; McTiernan was replaced by Renny Harlin.[153] Die Hard 2 is notable for being the last film in the series to feature the involvement of De Souza, Bedelia, Veljohnson, and Atherton. It was also the last film to involve Silver and Gordon, who fell out with each other and Willis after filming concluded, delaying the production of a third film—Die Hard with a Vengeance.[153][154][155] This sequel also took longer to develop because of the difficulty in scripting an original scenario that had not already been used by one of Die Hard's many imitators.[155][153] McTiernan returned to direct Die Hard with a Vengeance; his second and final time in the series.[98] The film's plot pits McClane against Hans Gruber's brother, Simon (Jeremy Irons).[153] It is considered one of the better Die Hard sequels.[156]

Live Free or Die Hard—also known as Die Hard 4.0— was released in 2007. The film features the first appearance of McClane's daughter since Die Hard (portrayed by Mary Elizabeth Winstead). McClane teams up with a hacker (Justin Long) to fight cyber terrorists led by Thomas Gabriel (Timothy Olyphant).[157][158] The film was controversial for its studio-mandate to target younger audiences, requiring much of the violence and profanity prevalent in the rest of the series to be excluded.[158] Even so, it was financially and critically successful.[159] The fifth film in the series, A Good Day to Die Hard, teams McClane up with his son Jack for an adventure in Moscow. The film was derided by critics; the reception was negative enough to stall the franchise. It is considered the weakest entry in the franchise, and a poor action film.[160][157][158] Despite its reception, the film earned over $304 million worldwide and is regarded as a financial success.[161][159] Willis has shown interest in making a sixth and final film.[153]

Die Hard remains the highest critically rated film in the series based on aggregated reviews.[162] As the sequels progressed, they increasingly hewed closer to the 80's style action films Die Hard had eschewed, with McClane becoming an invincible killing machine surviving damage that would have killed his original incarnation.[10][163] NPR called Die Hard a "genuinely great" movie whose legacy has been tarnished by lackluster sequels.[164] According to The Guardian, the evolution of the action genre can be tracked by the differences in each Die Hard sequel, as McClane evolves from human into superhuman.[96] A comic book prequel and sequel have been released: Die Hard: Year One is set in 1976 and chronicles McClane as a rookie officer; A Million Ways to Die Hard is set 30 years after Die Hard, and features a retired McClane seeking out a serial killer.[165][166]

References

Notes

- While The Numbers and Box Office Mojo provide North American box offices, they do include the international figures for many 1988 films. When failing to take into account the international grosses of some films, Die Hard is the eight-highest-grossing film worldwide of 1988. Based on other reports in 1988, particularly by Variety, the worldwide grosses of Cocktail and A Fish Called Wanda were higher than Die Hard's, lowering it to the tenth-highest-grossing film overall.[59][57][60]

References

- Mottram, James; Cohen, David S. (November 5, 2018). "Book Excerpt: Inside the Making of 'Die Hard' 30 Years Later". Variety. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Power, Ed (November 26, 2018). "Die Hard at 30: How the every-dude action movie defied expectations and turned Bruce Willis into a star". The Independent. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Collins, K. Austin (July 13, 2018). "Die Hard Is as Brilliantly Engineered as a Machine Gun, Even 30 Years Later". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Zoller Seitz, Matt (July 15, 2013). ""Die Hard" in a building: an action classic turns 25". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Harmetz, Aljean (February 16, 1988). "If Willis Gets $5 Million, How Much for Redford?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Bailey, Jason (July 10, 2018). "How Die Hard Changed the Action Game". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Hewitt, Chris (March 9, 2007). "Empire Essay - Die Hard Review". Empire. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- "Bruce Willis personally picked Bonnie Bedelia as his Die Hard costar". Start TV. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Frazier, Dan (August 24, 2015). ""There is no such thing as an action movie." Steven E. de Souza on Screenwriting". Creative Screenwriting. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- Vlastelica, Ryan (December 11, 2017). "The novel that inspired Die Hard has its structure, but none of its holiday spirit". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Doty, Meriah (February 13, 2013). "Actors who turned down 'Die Hard'". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on June 25, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- Gharemani, Tanya (June 23, 2013). "A History of Iconic Roles That Famous Actors Turned Down". Complex. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- Rothman, Michael (June 23, 2013). "'Die Hard' turns 30: All about the film and who could have played John McClane". ABC News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- Lawrence, Christopher (August 30, 2016). "Las Vegan's polling company keeps tabs on Hollywood". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- Modderno, Craig (July 3, 1988). "Willis Copes With the Glare of Celebrity". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Ramis Stiel, Violet (July 14, 2016). "On My Dad Harold Ramis and Passing the Ghostbusters Torch to a New Generation of Fans". Vulture. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- Harmetz, Aljean (July 25, 1988). "Big Hollywood Salaries A Magnet For The Stars (And The Public)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Harmetz, Aljean (February 18, 1988). "Bruce Willis Will 'Die Hard' For $5 Million". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 13, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- Gross, Ed (June 6, 2018). "'Die Hard' Is 30 — Meet the 1988 Bruce Willis in a Recovered Interview (EXCLUSIVE)". Closer. Archived from the original on March 17, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters - 17. Hans Gruber". Empire. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- Pearson, Ben (July 12, 2018). "'Die Hard' 30th Anniversary: The Cast and Crew Reflect on the Making of an Action Classic [Interview] - Reginald VelJohnson Interview". /Film. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Bianco, Julia (March 8, 2018). "The untold truth of Die Hard". Looper.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Brew, Simon (November 6, 2012). "Hart Bochner interview: Ellis in Die Hard, directing, and more". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Pearson, Ben (July 12, 2018). "'Die Hard' 30th Anniversary: The Cast and Crew Reflect on the Making of an Action Classic [Interview] - Steven E. de Souza Die Hard Interview". /Film. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Kirk, Jeremy (July 19, 2011). "31 Things We Learned From the 'Die Hard' Commentary Track". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- Pecchia, David (November 1, 1987). "Films going into production:DIE HARD (Gordon..." Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- "Die Hard". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- Harmetz, Aljean (May 26, 1988). "Hollywood Opens Its Summer Onslaught". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Pearson, Ben (July 12, 2018). "'Die Hard' 30th Anniversary: The Cast and Crew Reflect on the Making of an Action Classic [Interview] - Jan de Bont Die Hard Interview". /Film. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Lussier, Germain (March 8, 2018). "I Went to Die Hard's Nakatomi Plaza and Not a Single Hostage Was Taken". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on November 22, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Fernandez, Alexia (August 10, 2018). "Die Hard 30 Years Later: Bruce Willis Was 'Distracted' by Demi Moore, Jokes Costar Bonnie Bedelia". People. Archived from the original on October 1, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Marsh, Steve (July 16, 2013). "10 Die Hard Tidbits We Learned From Its Biggest Scene-Stealers". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Daly, Rhian (March 5, 2017). "'Die Hard' co-writer explains 29-year-old plot hole". NME. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Abrams, Simon (November 12, 2018). "Die Hard's Director Breaks Down Bruce Willis's Iconic Roof Jump". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Lichtenfield 2017.

- "Die Hard". bbfc.co.uk. August 8, 1988. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- "Die Hard's Debt to A Clockwork Orange and Beethoven". Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- Shivers 1995, p. 13.

- Shivers 1995, pp. 13,16.

- "Filmtracks: Die Hard (Michael Kamen)". Filmtracks.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- Vlastelica, Ryan. "AllMusic Review by Neil Shurley". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Smith, Giles (January 20, 1994). "POP / Interview: The man who gets all the credits: When the composer Michael Kamen gave us 'Everything I Do', it hung around for months. Now 'All for Love' looks set to do the same. Can we forgive him? Giles Smith thinks so". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Shivers 1995, p. 16.

- Hart, Ron (December 21, 2017). "Run-D.M.C.'s 'Christmas In Hollis' at 30: Darryl McDaniels on Keith Haring, 'Die Hard' & His 'Real' Rhyme". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- Greenstreet, Rosanna (July 7, 2007). "Q&A". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Meares, Hadley (December 13, 2019). "The real-life tower that made 'Die Hard'". Curbed. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Failes, Ian (August 13, 2018). "The Science Project That Resulted in 'Die Hard's Most Killer Stunt". Thrillist. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Harmetz, Aljean (September 6, 1988). "A Blockbuster Summer of Blockbusters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Broeske, Pat H. (July 17, 1988). "High-Rising Career". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ""Die Hard" Los Angeles Premiere - July 12, 1988". Getty Images. July 12, 1988. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- Harmetz, Aljean (August 15, 1988). "'Last Temptation' Sets a Record as Pickets Decline". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Voland, John (July 19, 1988). "Weekend Box Office : Audiences Make Eastwood's Weekend". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- "Weekend Domestic Chart for July 22, 1988". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- "Weekend Domestic Chart for July 29, 1988". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- "Die Hard (1988) - box office". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- "Die Hard (1988) - summary". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- "1988 Worldwide Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.