DNA Doe Project

DNA Doe Project (AKA DNA Doe Project, Inc. or DDP) is an American non-profit volunteer organization formed to identify unidentified deceased persons (commonly known as John Doe or Jane Doe) using forensic genealogy. Volunteers identify victims of automobile accidents, homicide, and unusual circumstances, and persons who committed suicide under an alias.[1] The group was founded in 2017 by Colleen Fitzpatrick and Margaret Press.

| |

| Formation | 2017 |

|---|---|

| Founders | Colleen Fitzpatrick and Margaret Press |

| Purpose | Body identification |

| Headquarters | Sebastopol, California, United States |

| Location |

|

Volunteers | 40+ |

| Website | www |

History

Colleen Fitzpatrick, who has a doctorate in physics, worked as a nuclear physicist with NASA and the US Department of Defense[2], was the founder of IdentiFinders, an organization that used Y-chromosomal testing to attempt to identify male killers in unsolved homicides.[2]

Margaret Press is a novelist who has also had careers in computer programming, speech, and language consulting.[3] She retired from computer programming in 2015 and relocated from Salem, Massachusetts to Sebastopol, California to live near family.[3] As a hobby, Press had begun working in genetic genealogy in 2007, helping friends and acquaintances find relatives, as well as helping adoptees find their biological parents.[3] After reading Sue Grafton's novel "Q" Is for Quarry, about a Jane Doe, Press hoped to use genetic genealogy to also identify unidentified homicide victims.[2]

In 2017, Fitzpatrick, Press and a small group of volunteers formed the volunteer-based, nonprofit DNA Doe Project (DDP), a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization based in Sebastopol, California.[3] The two, along with many volunteers, use genetic and traditional genealogy sources in conjunction with DNA from unidentified victims and working with local law enforcement agencies to build family trees through GEDmatch, a free public DNA database. Through this process, they have been able to identify some persons in cold cases.[2]

In March 2018, the DNA Doe Project announced it had solved its first case. Known for decades as the "Buckskin Girl," the victim was identified as Marcia Lenore Sossoman (King). Her father had died in 2018 a few months before the identification was made, but other family members gathered to commemorate Marcia Sossoman (King) when they unveiled a new gravestone bearing her name at her grave in Riverside Cemetery, Miami County, Ohio.[4]

In May 2019, GEDmatch required people who had uploaded their DNA to its site to specifically opt in to allow law enforcement agencies to access their information. This change in privacy policy was forecast to make it much more difficult in the future for law enforcement agencies to solve cold cases using genetic genealogy.[5]

Procedure

Typical steps

Each genetic genealogy case at the DNA Doe Project generally is conducted by the following steps:

- Acceptance of case from law enforcement

- Extraction of DNA sample (sometimes repeated if the first sample proves too degraded for analysis)

- Fundraising for DNA sequencing

- Sequencing of DNA sample

- Bioinformatics "translates" the DNA sequencing into a digital data file that is compatible with GEDmatch

- Uploading DNA data file to GEDmatch

- Genealogical analysis using GEDmatch and other tools

- Tentative identification of the Doe

- Law enforcement verifies identity, typically using fingerprints or a DNA sample provided by an immediate relative

Difficulties

Some of the difficulties the DNA Doe project encountered when using genetic genealogy to identify bodies have been:[6][7]

- Adoptions into the family tree, which interrupt the genetic genealogy. Fitzpatrick described this as having to "solve a mystery to solve a mystery," This is the case with the Park County John Doe found in 1974.

- Ethnicities for which there are not yet large DNA databases, such as Native American and African American. The Apache Junction Jane Doe found in Arizona in 1992 has not yet been identified for this reason.[8] It took extra time to identify Lyle Stevik. Stevik was believed to be of Native American ancestry while the Apache Junction Jane Doe is thought to be of African American ancestry.

- Persons descended from or who are themselves recent immigrants to the United States, for whom there would not be ancestral genealogy records in the US. For example, Philadelphia Jane Doe is now thought to have had ancestors from Australia and Malta.

- Intermarriage among related families (endogamy), making discernment of the lines of descent and individuals more difficult. Such families were encountered by researchers in the "Belle in the Well" and Stevik cases.

- Amounts of DNA being too small for adequate testing, especially with difficult bone extractions. This status could require multiple extractions for a suitable sample.

- Degraded DNA. This was a condition encountered in the Joseph Newton Chandler III case, Corona Girl case, and Lime Lady case.

- Bacterial/Human contamination, reducing the amounts of the Doe's DNA that can be used for analysis, which usually isn't discovered until sequencing is complete. The Sumter County Does' DNA was contaminated with bacteria, and two does from Washington had to be put on hold due to contamination

- Exceedingly large family trees, which can cause investigations to take weeks or months. This was the case with Joseph Henry Loveless, and is the case with the Kings County and Pulaski County Jane Does.

Cases

2018 identifications

Marcia Lenore Sossoman (King), AKA "Buckskin Girl"

In 1981, police found a female murder victim in a ditch in Troy, Ohio. Because the victim was found wearing a distinctive buckskin coat, she was given the name "Buckskin Girl" as the investigation continued. For decades, authorities sought the woman's identity, but to no avail.[4][9]

At the 2017 American Academy of Forensic Sciences conference, Elizabeth Murray, an Ohio forensic anthropologist, met Colleen Fitzpatrick and Margaret Press, founders of the DNA Doe Project, who discussed what genetic genealogy techniques could do for this case. The victim's body had long since been buried, but a vial of blood had been held in a lab for 37 years. The vial had not been refrigerated, however, resulting in the DNA becoming highly degraded, with only 50–75% of markers remaining. With the help of Greg Magoon, a senior researcher at Aerodyne Research, they were able to upload this DNA data to GEDmatch.[4][9]

From this point, the DNA Doe Project was able to identify the "Buckskin Girl," based on a very close DNA match (to a first cousin once removed).[10] Her name was Marcia Lenore Sossoman (King) from Arkansas, age 21 at the time of her death. DNA Doe Project volunteers provided law enforcement with the name of a close relative of King's who lived in Florida. This relative volunteered a DNA sample that confirmed Sossoman's identity. This sample proved to be a match.[4]

After 37 years, her mother was still living at the house where Sossoman had grown up. She had refused to move or change her phone number in hopes that her daughter might return or try to contact her.[4][9]

Lyle Stevik

In September 2001, a man was found to have hanged himself in a motel in Amanda Park, Washington, a town on the Olympic Peninsula. The man had checked in as "Lyle Stevik," which appeared to be an alias. This name appeared drawn from "Lyle Stevick", a character in a Joyce Carol Oates's novel You Must Remember This (1987).

The Grays Harbor County Sheriff's Office spent countless hours in search of the man's true identity, but to no avail.[11][12][13][14]

In 2018, the DNA Doe Project took the case at the request of the County Sheriff's Office. In order to raise the funds required to complete the necessary DNA analysis, the DDP set up its first-ever "Doe Fund Me" campaign on behalf of the victim. The campaign was a quick success, as by this time "Stevik" had gained Internet fame among web sleuths. Adequate funds were raised within 24 hours. By 22 March 2018, DDP volunteers had obtained his DNA results and began analyzing through GEDmatch and related genetic genealogy research.[11][12][13][14]

After about 20 volunteers put hundreds of hours into the case, they found a candidate in a 25-year-old young man from California. Authorities contacted the man's family, who conclusively verified his identity using fingerprint samples taken in his childhood. The family has requested that Stevik's identity remain private.[11][12][13][14]

Robert Ivan Nichols, AKA Joseph Newton Chandler III

Joseph Newton Chandler III, a resident of Eastlake, Ohio, committed suicide in his apartment on July 24, 2002. As authorities sought to identify his heirs, they discovered that his name and identity were fake. The real Joseph Newton Chandler III had died in a Sherman, Texas car accident at age eight on 21 December 1945. The suicide victim had stolen the boy's identity in 1978, while living in South Dakota. Authorities began a search for the man's true identity.[15][16][17][18][19]

Extracting DNA proved difficult, as the victim's remains had been cremated. In the year 2000, however, two years before his death, the victim had had a tissue sample taken for a medical treatment. Authorities obtained this sample, but genetic analysis of the sample using traditional law enforcement techniques yielded few clues. In 2016, authorities reached out to IdentiFinders, a company run by Colleen Fitzpatrick, for help. In examining the man's Y-DNA signature, they determined that his true last name was likely "Nicholas" or some variation.[15][16][17][18][19]

Chandler became the first case for the DDP. They analyzed the autosomal DNA[4] of the highly degraded sample of the man's DNA, which had been stored in paraffin for about 15 years. Despite the obstacles, and after over 2,500 hours of work,[2] the DDP researchers were able to conclusively determine in June 2018[17] that Joseph Newton Chandler III, was Robert Ivan Nichols, son of Silas and Alpha Nichols of New Albany, Indiana. This identification was verified when Robert's son, Phillip Nichols, volunteered a DNA sample, which proved to be a match.[15][16][17][18][19]

Mary Silvani, AKA "Washoe County Jane Doe"

The body of a woman aged between 25 and 35 years was found by hikers on July 17, 1982 in Sheep Flats, Washoe County, Nevada. The woman had been shot in the back of the head as she was bending over, possibly to tie her shoes. The bullet hole on her head had been covered with men's underwear.

The victim wore a light pair of tennis shoes, a sleeveless blue shirt, jeans with a blue bikini bottom in a pocket, and a blue swimsuit underneath. The shirt had been sold at stores in California, Washington, and Oregon.

At the victim's autopsy, a vaccination scar was found on her left arm, and another on her abdomen. In addition, one of her toenails had a large bruise underneath. Evidence from the style of dental work she had received indicated that she may have lived in Europe at some point during life. This theory has since been disproved. The woman had hazel eyes, was around five feet five inches in height, weighed 112 pounds, and had brown hair tied back in a bun. 231 people have been ruled out as possible identities of the decedent.

During the years when police struggled to identify her, she was known as "Sheep Flats Jane Doe" or "Washoe County Jane Doe".

In July 2018 it was announced that she had been tentatively identified through genetic genealogy by the DNA Doe Project. In September 2018 her identity was confirmed by the Washoe County Sheriff's Office. However the Sheriff's Office withheld further information due to its ongoing homicide investigation.

In May 2019 the Washoe County Sheriff's Office announced that Washoe County Jane Doe is 33-year-old Mary Edith Silvani. She was born in Pontiac, Michigan, and grew up in the Detroit area. She later moved to California as an adult.[20]

"Alfred Jake Fuller"

A man aged 40 to 46 was discovered in his apartment in Oakland, Maine, after having died on May 2, 2014, from what were determined to be natural causes.[21] He registered under the name "Alfred Jake Fuller" and provided a birth date of November 8, 1970. No records were found to match this information, leading investigators to speculate he used an alias. The man was estimated to be 5'10", at a weight of 255 pounds. He wore a short goatee and had curly brown hair. A blue "discoloration was on the left side of his face and a large nevus was in between his shoulders. His personal items included a prepaid Visa card and a "fugitive recovery agent" document. He was fully clothed and wore two pieces of jewelry on his neck.[6][22][23]

In 2018 the DNA Doe Project took on his case and was able to identify him that year. His family requested that his identity be withheld for privacy.[24]

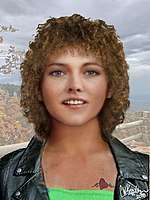

Tracey Hobson AKA "Anaheim Jane Doe"

The extensively decomposed remains of a young female were found at the side of a freeway in the Santa Ana Canyon in Anaheim, California, on August 30, 1987. The victim's body had almost completely skeletonized at the time of discovery, although some fragments of soft tissue were still present upon the remains. The victim—originally called "Anaheim Jane Doe" and also known as Jane Doe 87-04092 EL—was a slender young woman who had medium-length light hair, estimated to have been between 15 and 19 years old when she died,[25] and was speculated to have been a teenage runaway.[26] Her hands had been cut off by her killer or killers, likely as a way to prevent identification via fingerprinting.[27]

At the crime scene, enough hair was found upon and near the body to determine that the decedent had either blond or light-brown hair, although no personal belongings beyond a red handkerchief were discovered with her remains. Her skull was forensically reconstructed by Shannon Collis in hopes of identifying the body, determining the decedent also had high cheekbones. One of her front teeth was slightly chipped, while three of her other teeth had visible cavities, and six molars were missing. She was estimated to be between five feet one to five feet four inches in height. It is believed that the victim had died approximately six weeks before her body was discovered, meaning she likely died in July 1987. She may possibly have died by repeated stab wounds to her chest area, as incisive damage to two of her ribs suggested.[28] Therefore, her death was ruled as a definite homicide.[29][30][31][32][33]

In 2018, the identity of Anaheim Jane Doe was established by the DNA Doe Project,[34] although due to the fact the case was an ongoing homicide investigation, her identity was not released to the media until January 2019. The decedent was 20-year-old resident of Anaheim named Tracey Coreen Hobson.[6][6][27][35]

Dana Dodd, AKA "Lavender Doe"

On October 29, 2006, the badly burned body of a female aged 17 to 25 was discovered in Kilgore, Texas. The victim's cause of death remained undetermined, yet the manner of death was ruled a homicide due to the fact that the body was set on fire deliberately and the victim had been raped.[36]

The DNA Doe Project took the case in 2018.[37][38] In January, the organization announced a tentative identification in the case, which would not be released until the suspect's trial concluded.[39] Despite this, Dodd's identity was released on February 11, 2019. She was 21 and last seen in Jacksonville, Florida.[40] Joseph Wayne Burnette, a long term person of interest in the case, confessed to the murder in August 2018, leading him to be charged with her death (and that of another female, 28 year old Felisha Pearson).[41][42]

2019 identifications

Darlene Norcross AKA "Butler County Jane Doe"

On March 7, 2015, skeletal remains of a white female were located near Tylersville Road in West Chester, Butler County, Ohio. The decedent was examined and estimated to be between 35 and 60 years old at the time of her death, which occurred as early as the fall of 2014. She had unique dental work, including implants. Her DNA did not match any profiles in national databases. In March 2019 she was identified as Darlene Wilson Norcross.[43] The cause, time and manner of her death are still undetermined.[44]

Anne Marie "Annie" Lehman, AKA "Annie Doe"

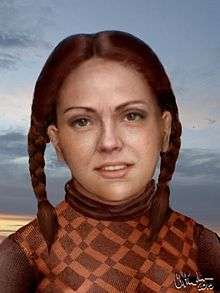

On August 19, 1971, the skeleton of a female aged 14 to 25 was discovered in Cave Junction, Oregon. She was white with reddish-colored hair, which was frosted blond. She was between 5'2" and 5'9" at around 125 pounds. She had slightly protruding upper front teeth and had some fillings in her teeth. Some debris was noted to partially conceal the remains, which were found near the border with California. A hunting knife with deer blood was near the bones.[45]

The decedent wore a checked pink and beige coat, a turtleneck shirt, 34B bra, blue and white underwear, Wrangler jeans and brown heeled shoes. She had several pieces of jewelry, one being a ring with the letters "AL" scratched into the mother of pearl stone. She also carried 38 cents, the oldest coin dated 1970.[46]

She was reported as wearing a New Zealand-made bra. DNA links were established with New Zealand and Sussex in the United Kingdom by the DNA Doe Project in 2018.[47][48]

Additionally, a map of northern California campgrounds was found in one of her pockets.[49]

The DNA Doe Project began work on the case in 2018 and through collaboration with NCMEC and NamUs, "Annie Doe" was identified as 16-year-old Anne Marie Lehman in March 2019, who was coincidentally known by the nickname "Annie" when alive.[50][51]

Dana Nicole Lowrey, AKA "Vicky Dana Doe"

On March 10, 2007, the remains of an unknown female were discovered in a wooded area of Marion County, Ohio. She was aged between 15 and 24 and had died between 2002 and 2006, most likely within the two years prior to her discovery. She was between five feet three to five feet nine inches tall and had brown, straight hair.[52] No clothing or personal effects were found with her body, which was completely skeletonized.

The female had unique physical characteristics. She was predominantly white, but could have had a degree of Hispanic or Asian heritage.[53] She had also suffered damage to one of her front teeth (although this dental damage may have occurred posthumously). She did appear to have otherwise taken considerable care of her teeth although there was no evidence that she had seen a dentist during her lifetime.[54]

In September 2016, authorities announced the possibility that this decedent was a victim of alleged serial killer Shawn Grate, who claimed he had killed this victim after encountering her selling magazines door-to-door.[55] Grate has stated he believes the decedent's name may have been Dana.[56] She was also called "Vicky" by investigators, as she was discovered near Victory Road.[57] In January 2018, the results of isotope analysis conducted upon her remains indicated she likely originated from the southern United States, possibly Texas or Florida.[58] In 2019, Police asked the DNA Doe Project to help identify the body.[57]

In June 2019 the victim had been identified. She was 23 at the time of her death in May 2006. She was originally from Minden, Louisiana. She was separated from her husband, with whom she had two young children.[59]

On September 11, 2019, Grate pleaded guilty to her murder and was sentenced to life in prison without parole plus 16 years.[60][61][62]

Louise Virginia Peterson Flesher, AKA "Belle in the Well"

Flesher was a woman whose remains were discovered in a well in Chesapeake, Ohio on April 22, 1981. She had been strangled to death and her murder is believed to have been committed between 1979 and 1981. She was nicknamed "Belle In the Well" based upon the circumstances of her discovery.[63]

The victim was believed between 30 and 60 years old at the time of her death and her body bore signs of arthritis in her back. She was about 5 feet 3 inches in height and weighed between 130 and 150 pounds. She had prominent front teeth and cheekbones, and wore multiple layers of clothing. In her possession were a Greyhound Bus ticket and a distinctive coin. In 2018 her autosomal DNA was analyzed by the DNA Doe Project,[64] and distant relatives were identified in Cabell County, West Virginia.[65][66] In July 2019, the decedent was identified as Louise Virginia Peterson Flesher.[67][68] Flesher was born 1915 (about 65 when she died), was native to West Virginia and the mother of three children. She had also resided in Wyoming prior to her death.[69] This case took 14 months and was particularly hard to solve because there was endogamy in her ancestors (the practice of marrying within a specific social group, caste or ethnic group). Volunteer researchers eventually constructed a family tree of 43,130 people before they identified her.[70]

A year prior to her identification, Flesher had been compared to the unidentified victim, yet she was believed to have been too old to be a match.[63]

Debra Jackson, AKA "Orange Socks"

Debra Jackson's body was found face-down and nude in a culvert along a highway in Georgetown, Texas on October 31, 1979. She had been sexually assaulted and strangled. Along with the pair of socks on her body, she also wore an abalone/mother of pearl stone on a ring.

At the time, Jackson was believed to have been a transient or a runaway. Strong evidence supported this, as she had keys from an Oklahoma motel, long, dirty nails, insect bites (revealed to actually be impetigo scars post-identification), unshaven legs and a makeshift sanitary pad. She had salpingitis due to having untreated gonorrhea.

Henry Lee Lucas confessed to her murder and was sentenced to death. It was later discovered that police officers from the area had him look at crime scene photos and then confess during interviews, which they would use to gain recognition for solving cold cases.

The DNA Doe Project took on the case in 2018. On August 6, 2019, Orange Socks was identified as 23-year-old Debra Louise Jackson, who was from Abilene, Texas.

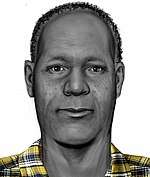

Nathaniel Terrance “Terry” Deggs AKA "Mill Creek Shed Man"

On January 11, 2015, the decomposed remains of a man were found in a shed in Mill Creek, Washington. It appeared as though the man, who is called Mill Creek Shed Man, had been living in the shed. He is thought to have died about a year before he was found, but it could have been longer. The man appeared to be between 50 and 65 years old, about 5’11” (some reports state 5’9,” some state 6’1”), and African American. The pinky finger on his right hand was missing. Other findings were a “prominent sternal fissure, healed nasal fracture, lumbar scoliosis, and arthritis.” No cause of death could be ascertained, and there were no signs of foul play. The following information is not confirmed, although it can be found online. There is “local lore” that states that our John Doe had permission to live in the shed from a man who once owned the property on which it was located. A man named Jerry Diggs/Deggs lived on the property where our John Doe was found, but there is no proof he and Mill Creek Shed Man are the same person. Jerry apparently gave his birth date as 12/31/1949. He claimed to be from the East Coast and to have worked as a security guard for a bank. He stated that he was struck in the head during a bank robbery and received a head injury. On September 26, 2019 the DNA Doe Project (DDP) proudly announced the successful identification of Mill Creek Shed Man. His name was being withheld by officials at the time. Snohomish County Medical Examiner's Office (SCMEO) confirmed the identity on September 2, 2019 by comparing the deceased DNA with DNA submitted by the man's sister, whose name was provided by DDP on August 6, 2019. In December his name was released 65-year-old Nathaniel Terrance “Terry” Deggs, originally from Baltimore, Maryland and later The Bronx, New York.[71]

Marcia Bateman AKA "I-196 Jane Doe"

Marcia Bateman's remains were discovered by a hunter not far from the intersection of I-196 and County Road 378 in Van Buren County, Michigan on Oct. 12, 1988. Nearly two months had passed since the 28-year-old was reported missing by her family in Oklahoma. While police in Oklahoma City were actively searching for Bateman, Michigan State Police Detective Sgt. Scott Ernestes said, a connection was never drawn between the remains in Michigan and the missing woman. She was finally identified in November 2019. While Bateman's death is ruled suspicious, Ernestes said there are no suspects.[72]

Michelle Carnall-Burton AKA "Marion County Jane Doe (1987)"

On September 21, 1987, the body of a woman was found in Marion County, Kansas. She had been bound at the hands and ankles, indicating she died from foul play. The victim was at least 16 years old, but most likely between twenty and thirty-five years old.[73] Her remains were located behind hay bales and hedges at the side of a road and may have been there for months. A tattoo of a cross was located on her shoulder, although most of her body was skeletonized. She was between five feet six inches and five feet eight inches tall and had brown, four-inch-long hair. She was found with healed fractures on her ribs, indicating she had been in some sort of accident months before she died.[74] In 2018 police asked the DNA Doe Project to help identify her.[75]

The victim was identified in December 2019 as Michelle Evon Carnall-Burton, aged 22 at the time of her murder. She had disappeared from Cherryvale, also south-east Kansas in 1986, and had lost contact with her family.[76]

Bertha Holguín AKA "Phoenix Jane Doe (1997)"

Bertha Alicia Holguín Barroterán's body was discovered in Phoenix, Arizona in October 1997. She was identified after relatives in New Mexico found out about the case due to greater media exposure.[77]

Joseph Henry Loveless AKA "Clark County John Doe"

The headless torso of a man was found in 1979, stashed in a burlap sack in Buffalo Cave, near Boise, Idaho. In 1991, a hand was located on the same site, leading to further excavations from which the other hand and legs were discovered. Identification was thought to be implausible, due to the missing head and the huge family tree of the deceased. However, thanks to an 87-year-old California man who agreed to take a DNA test, the remains were identified as those of his grandfather – bootlegger and accused murderer Joseph Henry Loveless. He had been accused of murdering his common-law wife in 1916, but managed to escape imprisonment by using a sawblade hidden in his shoe. The circumstances surrounding his death are, at present, unknown; however, it is believed that he died soon after his escape, as he was found wearing the clothes detailed in his wanted poster. By far, this has been DNA Doe Project's oldest solved case.[78]

2020 identifications

Kraig Patrick King, AKA "Barron County John Doe (1982)"

The skeleton of a young man was discovered by loggers on September 21, 1982, in Dallas, Barron County, Wisconsin. This decedent was estimated to be between 18 and 24 years old at the time of his death. Basic estimations, such as the height, weight and hair color were later calculated. He was about 5 feet 7 to 5 feet 9 inches tall and likely weighed 180 to 195 pounds, with a large build. Hair found with the body was light brown.

It is believed that the decedent had been stabbed to death; this was indicated by tears in his western-style plaid shirt. He was also wearing jeans, a denim jacket, and blue shoes with white stripes.

Some distinctive elements as to the victim were also noted. It is possible that he wore glasses, although none were found at the scene. He had received a large amount of dental work in life; this had been performed shortly before he died. He had also had some kind of surgery on his left knee that involved a screw and staple in the tibia. This kind of surgery would have required an extensive hospitalization period that could have lasted up to six months. Serial numbers on the screw and staple were traced, but this did not lead to the location where they had been purchased.[79]

In December 2019, the DNA Doe Project announced a tentative match for this victim. On January 7, 2020, the Barron County Sheriff's Department and the DNA Doe Project announced that, via matches with familial DNA samples, the victim was confirmed to be Kraig Patrick King (b. 1961), of White Bear Lake, Minnesota. King was last seen alive in fall 1981, and law enforcement believe he was murdered in April or May 1982. Investigation of his homicide is ongoing.[80]

Sue Ann Huskey, AKA "Corona Girl"

On September 25, 1989, the remains of a female thought to be 18–24 were located in Williamson County, Texas along Interstate 35. She was about 5'2" tall at a weight between 110 and 120 pounds. Her ears were pierced, but only one earring was recovered. The victim also wore a necklace containing a white bead in the center, surrounded by two gold-colored beads on either side. She wore a white shirt with the words "Cinco De Corona" with the bottom cut into fringe, leading to her nickname; black pants, and a shirt cut into a bra with the words "American Legends" bearing a Native American design. She wore bikini panties and no shoes. The victim was shot to death.[81]

On January 14, 2020, after several unsuccessful attempts to create a usable file, it was announced that a match to Sue Ann Huskey was confirmed. Huskey was seventeen at the time of her murder and was originally from Sulphur Springs, Texas.[82][38] The match was made possible after the International Commission on Missing Persons was able to extract DNA from dental and bone remains, after decades of attempts by national laboratories.[83]

John H. Frisch, AKA "Peoria County John Doe"

On November 13, 2016, a male torso was found in the Illinois River in Schuyler County, and a skull was later found on June 12, 2017, in Kingston Mines. The remains were named the Peoria County John Doe. According to the Peoria County Coroner, the decedent died from blunt force trauma to the head. On January 27, 2020, the remains were identified as 56-year-old John H. Frisch. Frisch was not reported missing, but used addresses in Peoria and Hawaii throughout his life, according to Peoria County Sheriff's Office. Investigators are retracing Frisch's days prior to his body being found. Mr. Frisch's parents are deceased, and he has very limited family in the area.[84][38]

Tamara Lee Tigard, AKA "Lime Lady"

On April 18, 1980, the mummified corpse of a woman was discovered on the banks of the North Canadian River close to Jones in Oklahoma County, Oklahoma. The presence of three gunshot wounds upon her body clearly indicated her death was a homicide.[85] One of these wounds contained clothing fibers and a dime that had been driven into the body by a .45 caliber bullet. Due to the fact quicklime that had been poured onto her remains in a likely attempt to accelerate decomposition, the woman became known as "Lime Lady".[85]

She was estimated to be between the ages of 18 and 25, five feet six inches tall and weighed approximately 115 to 120 pounds. She had a heart tattoo on her chest as well as an appendectomy scar. It is believed that she may have been murdered by a biker gang earlier in the year or in 1979, although some contemporary reports indicate she may have been deceased for as little as ten days. Multiple facial reconstructions of the decedent have been created, and her DNA was extracted for profiling in 2014.[86][87] The DNA Doe Project began DNA testing in 2019, and was able to generate a usable profile by the end of the year.[88]

It was announced on January 30, 2020 that the victim was identified as 21-year-old Tamara Lee Tigard, last known to reside in Las Vegas, Nevada.[89][90]

Ginger Lynn Bibb AKA "Phoenix Jane Doe (2004)"

On April 21, 2004, a woman's skeletal remains were found rolled up in a carpet in Phoenix, Arizona. In February 2020, she was identified as Ginger Lynn Bibb.[91]

Gary Albert Herbst AKA "Barron County John Doe (2017)"

On December 3, 2017, a fragment of a human skull was found on the driveway of a rural residence in Dallas, Wisconsin. Investigators determined that it belonged to a white/Asian-American male between 35 and 55 years old. Investigators determined the cause of death as homicide by a gunshot wound to the head. [92] Forensic genealogy began on February 25, 2020, and a potential candidate was revealed in less than two days. On June 23, 2020, the doe in which the skull belonged to was positively identified as Gary Albert Herbst. This also marks the first Doe to be identified through the project who did not have a forensic reconstruction made.[93]

Jerry Holbert AKA "Kingsport John Doe"

On August 11, 2003, the decomposed body of a middle aged or elderly white male was found in the Holston River near Riverfront Park in Kingsport, Tennessee. Investigators could not find any sign of foul play and believe that the man had possibly drowned. He also could have washed to the place he was found from anywhere upstream. He was believed to be in the river for between seven and ten days. The man was estimated to be between 40 and 80 years old, was between 5 feet 10 inches and 6 feet tall, and weighed between 170 and 180 pounds. He had gray hair and was clean shaven. Eye color could not be ascertained. He was found wearing a pair of blue jeans, a black belt, a white sleeveless button-up shirt with blue and burgundy stripes and a pair of black shoes. The man's description did not match any missing person report in the area, and his fingerprints did not match any in any federal database. The man was found to be missing most of his teeth.

On August 6, 2020, the Kingsport Police Department announced that the decedent was 64-year-old Jerry D. Holbert from Charleston, West Virginia. Holbert, who suffered from dementia, was reported missing on August 4, 2003, after he left his residence and heading to the bus station, planning to visit a relative in Ohio. Circumstances indicate that no foul play was involved.[94]

Ongoing cases

Following is a chart of the DNA Doe Project's ongoing cases, along with an indication of where each case is in the process:

| Name | Unidentified remains discovered | Status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Place | ||

| Pillar Point Doe[95] | 26 November 1983 | Half Moon Bay, California | Tentatively identified[96][97] |

| John Clinton Doe[98] | 26 November 1995 | Bradford Township, Wisconsin | Tentatively identified[99][100] |

| Philadelphia Jane Doe[101] | 10 December 2017 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Tentatively identified[38][102] |

| Park County John Doe | 11 February 1974 | Grant, Colorado | Genealogical analysis[38][103] |

| Nation River Lady | 3 May 1975 | Casselman, Ontario | Genealogical analysis[104] |

| Grundy County Jane Doe | 2 October 1976 | Erienna Township, Illinois | Genealogical analysis[38] |

| Delafield John Doe | 14 September 1977 | Delafield, Wisconsin | Genealogical analysis[38][105] |

| Kern County Jane Doe 1980[106] | 14 July 1980 | Delano, California | Genealogical analysis [38][107] |

| Ventura County Jane Doe[106] | 18 July 1980 | Westlake Village, California | Genealogical analysis[38][108] |

| Rockledge Jane Doe[109] | 11 October 1980 | Rockledge, Florida | Genealogical analysis[110] |

| Pulaski County Jane Doe | 25 May 1981 | Dixon, Missouri | Genealogical analysis[38][111] |

| Plainview Jane Doe | 16 February 1982 | near Plainview, Texas | Genealogical analysis[38][112] |

| Twinsburg John Doe | 18 February 1982 | Twinsburg, Ohio | Genealogical analysis[38] |

| Vernon County Jane Doe | 4 May 1984 | Westby, Wisconsin | Genealogical analysis[38][113] |

| Lee County John Doe | 17 November 1984 | Giddings, Texas | Genealogical analysis[114] |

| Harper Jane Doe | 10 February 1987 | Detroit, Michigan | Genealogical analysis [38][115] |

| Tom Green County John Doe[116] | 15 November 1987 | Twin Buttes Reservoir, Texas | Genealogical analysis[38][117] |

| Charlene | 5 August 1988 | Morocco, Indiana | Genealogical analysis[38][118] |

| Julie Doe[119] | 25 September 1988 | Clermont, Florida | Genealogical analysis[38][120] |

| Rebel Ray | 3 October 1988 | Georgetown, Texas | Genealogical analysis[38][121] |

| New Britain Jane Doe[122] | 11 October 1991 | New Britain, Connecticut | Genealogical analysis[38][123] |

| Apache Junction Jane Doe[124] | 6 August 1992 | Apache Junction, Arizona | Genealogical analysis[125] |

| Betty The Bag Lady | 23 August 1992 | New Buffalo, Michigan | Genealogical analysis[38][126] |

| Kenosha John Doe[127] | 27 August 1993 | Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin | Genealogical analysis[128] |

| Trabuco Canyon John Doe | 13 December 1996 | Trabuco Canyon, California | Genealogical analysis[38][129] |

| Monique | 4 February 1997 | Phoenix, Arizona | Genealogical analysis[38][130] |

| Butler County John Doe[131] | 18 May 1997 | Fairfield Township, Ohio | Genealogical analysis[132] |

| Lenawee County John Doe | 19 November 1997 | Blissfield Township, Michigan | Genealogical analysis[38][133] |

| Jonesport John Doe | 24 July 2000 | Jonesport, Maine | Genealogical analysis[38][134] |

| Simpson County Jane Doe | 9 October 2001 | Franklin, Kentucky | Genealogical analysis [38][135] |

| Flathead County John Doe | 26 October 2003 | Marion, Montana | Genealogical analysis[38][136] |

| Broadway Street Jane Doe | 21 November 2004 | Phoenix, Arizona | Genealogical analysis[38][137] |

| Chattanooga-Birchwood John Doe | 28 August 2006 | Hamilton County, Tennessee | Genealogical analysis[38][138] |

| La Vergne Jane Doe | 14 November 2007 | La Vergne, Tennessee | Genealogical analysis[38][139] |

| Kenora Jane Doe | 17 June 2009 | Kenora, Ontario | Genealogical analysis[38] |

| Van Buren County John Doe 2010 | 29 October 2010 | Covert Township, Michigan | Genealogical analysis[38][140] |

| Mecklenburg County Jane Doe | 17 March 2011 | Charlotte, North Carolina | Genealogical analysis[38][141] |

| Kern County Jane Doe 2011 | 29 March 2011 | Arvin, California | Genealogical analysis[38][142] |

| Peter Kalama Lane Jane Doe | 6 November 2013 | near Yelm, Washington | Genealogical analysis[38][143] |

| West Manchester John Doe[144] | 18 November 2013 | York, Pennsylvania | Genealogical analysis[145] |

| Allegan County John Doe | 31 July 2014 | Ganges Township, Michigan | Genealogical analysis[38][146] |

| Carson City Jane Doe | 17 March 2015 | Carson City, Nevada | Genealogical analysis[38][147] |

| Kings County Jane Doe | 13 May 2015 | Corcoran, California | Genealogical analysis[148] |

| Portland Jane Doe | 22 May 2015 | Portland, Maine | Genealogical analysis[38][149] |

| Summit County John Doe | 10 July 2016 | Breckenridge, Colorado | Genealogical analysis[38][150] |

| St. Tammany Parish John Doe | 29 July 2016 | St Tammany Parish, Louisiana | Genealogical analysis[38][151] |

| Buena Vista Leg[152] | 28 July 2018 | Buena Vista Lake, California | Genealogical analysis[153] |

| Jefferson County John Doe | 10 March 2019 | Dandridge, Tennessee | Genealogical analysis[38][154] |

| Bedford Jane Doe | 6 October 1971 | Bedford, New Hampshire | Sequencing[38][155] |

| Houston John Doe | 9 August 1973 | Houston, Texas | Sequencing[38][156] |

| Sumter County John Doe | 9 August 1976 | Sumter County, South Carolina | Sequencing[38] |

| Sumter County Jane Doe | 9 August 1976 | Sumter County, South Carolina | Sequencing[38] |

| Jackson County John Doe | 15 August 1978 | Township of Knapp, Wisconsin | Sequencing[157] |

| Reservation Road Jane Doe | 19 October 1981 | Olympia, Washington | Sequencing[38][158] |

| Live Oak Doe[95] | 10 July 1986 | Live Oak, Texas | Sequencing[38] |

| Van Buren County John Doe 1987 | 24 December 1987 | Keeler Township, Michigan | Sequencing[38][159] |

| Grays Harbor County Jane Doe | 24 October 1988 | Elma, Washington | Sequencing[38][160] |

| Grant County John Doe | 9 April 1989 | Williamstown, Kentucky | Sequencing[38][161] |

| Marion County John Doe 1989[162] | 19 July 1989 | Marion County, Ohio | Sequencing[38] |

| Le Flore County Jane Doe | 18 January 1990 | Big Cedar, Oklahoma | Sequencing[38][163] |

| Kent County Jane Doe | 31 July 1997 | Ada Township, Michigan | Sequencing[38][164] |

| Redondo Jane Doe | 22 August 2001 | Redondo Beach, California | Sequencing[38][165] |

| Charlotte John Doe | 24 December 2008 | Charlotte, North Carolina | Sequencing[38][166] |

| Startex Jane Doe | 26 October 2011 | Startex, South Carolina | Sequencing[38][167] |

| Evangeline Parish Jane Doe | 18 December 2018 | Ville Platte, Louisiana | Sequencing[168] |

| Hudson John Doe | 16 August 2019 | Hudson, Ohio | Sequencing[169] |

| Columbia County Jane Doe | 8 May 1982 | Caledonia, Wisconsin | Extraction[38][170] |

| Adam | 18 October 1983 | Lake Village, Indiana | Extraction[38][171] |

| Jane Doe B-10 | 21 March 1984 | Seattle, Washington | Extraction[38][172] |

| Mowry Avenue Jane Doe | 24 October 1985 | Newark, California | Extraction[38][173] |

| Tukwila Jane Doe | 8 January 1997 | Tukwila, Washington | Extraction[38][174] |

| Jane Doe B-20 | 21 August 2003 | Kent, Washington | Extraction[38][175] |

| Smith County John Doe | 23 December 2004 | Tyler, Texas | Extraction[176] |

| Johnson County John Doe | 11 December 1972 | Johnson County, Texas | Awaiting additional extraction[38][177] |

| Alachua County John Doe | 13 February 1979 | Alachua County, Florida | Awaiting additional extraction[38][178] |

| Hartford Circus Fire Jane Doe 2109 | 6 July 1944 | Hartford, Connecticut | Stalled[38][179] |

| Hartford Circus Fire Jane Doe 4512 | 6 July 1944 | Hartford, Connecticut | Stalled[38][180] |

| Sultan Basin Road John Doe[181] | 10 April 2007 | Sultan, Washington | Stalled[38] |

| Beckler River Road Jane Doe[182] | 10 October 2009 | Skykomish, Washington | Stalled[38] |

References

- Bowman, Nancy (2018-05-11). "How they did it: Groundbreaking technology reveals ID in 37-year-old cold case". Dayton Daily News. Archived from the original on 2018-09-27. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- Testa, Jessica (2018-09-22). "Nobody Was Going To Solve These Cold Cases. Then Came The DNA Crime Solvers". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- Hillin, E.I. "Finding Jane Doe's real name: Local DNA sleuth is on the case". Sonoma West Times. Archived from the original on 2018-08-13. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- Augenstein, Seth (16 Apr 2018). "'Buckskin Girl' Case Break Is Success of New DNA Doe Project". Forensic Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Aldhous, Peter (2019-05-19). "This Genealogy Database Helped Solve Dozens Of Crimes. But Its New Privacy Rules Will Restrict Access By Cops". BuzzFeed News. Archived from the original on 2019-05-19. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- Augenstein, Seth (2019-01-10). "DNA Doe Project Names 3 More, Notes Case Patterns". Forensic Magazine. Archived from the original on 2019-01-10. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- "FAQ". DNA Doe Project Cases. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- abc15.com staff (2019-02-19). "Modern technology used to solve Valley cold cases". KNXV ABC 15 Arizona News. Archived from the original on 2019-02-23. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- ""Buckskin Girl" case: DNA breakthrough leads to ID of 1981 murder victim". CBS News. 12 Apr 2018. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Zhang, Sarah (April 27, 2018). "How a Genealogy Website Led to the Alleged Golden State Killer". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- Murphy, Neil (19 May 2018). "Internet sleuths finally solve riddle of mystery man 'Lyle Stevik' whose suicide ignited numerous conspiracy theories during 9/11 aftermath". Mirror. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Pepi, Kirk (14 May 2018). "One of the Internet's Favorite Mysteries Has Been Solved". Mel Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Lyle Stevik Identified; Closing 16 1/2 Year Old Unsolved Case". KXRO News. 8 May 2018. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Augenstein, Seth (9 May 2018). "DNA Doe Project IDs 2001 Motel Suicide, Using Genealogy". Forensic Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Augenstein, Seth (June 2018). "DNA Doe Project Names Another, Giving Major Piece in Infamous Ohio Mystery". Forensic Magazine. Forensic Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Metzger, Stephanie. "How did authorities solve the true identity of Joseph Newton Chandler III?". wkyc3. WKYC. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Caniglia, John. "Authorities solve cold case of war hero who hid behind dead boy's identity". Cleveland.com. cleveland.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Grzegorek, Vince. "Mystery of Identity of Ohio Man Who Hid Behind Fake Name for Years Solved, Mystery of Why Remains". clevescene.com. Clevescene.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Pepi, Kirk. "The Man Who Woke Up As An 8-Year-Old Boy". Mel Magazine. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Murphy, Heather (2019-05-11). "How Volunteer Sleuths Identified a Hiker and Her Killer After 36 years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-05-13. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Augenstein, Seth (10 January 2019). "DNA Doe Project Names 3 More, Notes Case Patterns". Forensic Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "Alfred Jake Fuller". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "NamUs #UP15432". www.namus.gov. National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. 1 July 2016. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- "DNA Doe Project". Facebook. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "Remains in Canyon are that of a Woman". Anaheim Bulletin. 1 September 1987. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "Remains in Canyon are that of a Woman". Anaheim Bulletin. 1 September 1987. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- "Orange County News Release". Orange County Sheriff. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Needham, John (17 August 1989). "ID-ing the Dead : Bodies of John and Jane Does Trigger Special Concern Among 34 Members of Coroner's Office". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Eddy, Steve (26 October 1987). "3D Techniques may ID dead Teen-Ager: Skull of girl found in canyon used in OC's first facial reconstruction". Orange County Register. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- Bishop, Alex (30 May 2013). "Unsolved Murder Spotlight: The Orange County Jane Doe". Crimelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- "Unidentified Jane Doe in 1987 in Aneheim California". Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Case File 22UFCA". The Doe Network. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Jane Doe 1987". National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Anaheim Jane Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- "Anaheim Jane Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Thomas, Sarah (4 October 2013). "Gregg County investigators seek to use new tech to crack cold case". News Journal. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- Coble, AnnaLise (2018-11-30). "EXCLUSIVE: New DNA Technology could help close local cold case". East Texas Matters, Nexstar. Archived from the original on 2018-12-06. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- "DNA Doe Project". Facebook. Archived from the original on 9 November 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "DNA DOE PROJECT: 'Lavender Doe' identified". KYTX. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "East Texas officials release identity of Lavender Doe". KLTV. 11 February 2019. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- "Police: Man confesses to 2018, 2006 killings of women in Gregg County". Longview News-Journal. 27 August 2018. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Staff (2019-02-11). "East Texas officials release identity of Lavender Doe". KLTV East Texas. Archived from the original on 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Staff, WLWT Digital (8 March 2019). "Officials identify human remains found 4 years ago in West Chester". WLWT. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- "Butler County Jane Doe, Cincinnati OH". DNA Doe Project Cases. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- "404UFOR". www.doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. 16 December 2004. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "NamUs UP# 10929". www.namus.gov. National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Mystery US skeleton has Kiwi DNA matches, and was wearing a New Zealand-made bra". Stuff (Fairfax) New Zealand. 3 May 2018. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- "47 year old US murder mystery linked to NZ through victim DNA and Kiwi-made bra". NZ Herald. 2018-11-09. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 2018-12-21. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "Jane Doe 1971". missingkids.com. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Annie Doe". DNA Doe Project Cases. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Josephine County Online – Press Release: Cold Case 17-940". www.co.josephine.or.us. 12 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Case File: 672UFOH". The Doe Network. August 8, 2014. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- "Jane Doe, #56 Unidentified remains". Ohio Attorney General. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- "Jane Doe 2007". missingkids.org. National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- "Shawn Grate Ohio Serial Killer: Timeline Of Five Murders, Names Of Women Victims And Facts To Know". www.morningnewsusa.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- Nist, Cassie. "Q&A from jail: Shawn Grate says his victims didn't want to live". Cleveland 19 News. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- "Vicky Dana Doe". DNA Doe Project Cases. Archived from the original on 2019-05-28. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- Volpenhein, Sarah (11 April 2018). "New tests could help identify alleged Shawn Grate victim in Marion County". Marion Star. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- "Marion County Sheriff identifying remains believed to be Shawn Grate's first victim". WTTE. 4 June 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- "Convicted killer Shawn Grate sentenced to another life term in Marion County death". 10TV. September 11, 2019. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- "Death-row's Grate gets prison term for Marion murder, his first". Mansfield News Journal. September 11, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- "Convicted serial killer Shawn Grate pleads guilty to Marion County murder". Cleveland19. September 11, 2019. Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- Hessler, Courtney (29 July 2019). "'Belle in the Well' ID'd". The Herald-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Augenstein, Seth (2018-04-16). "'Buck Skin Girl' Case Break Is Success of New DNA Doe Project". Forensic Magazine. Archived from the original on 2018-11-09. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "NamUs #UP6259". www.namus.gov. National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. 25 November 2009. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "1027UFOH". www.doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- MORRIS, JEFF (2019-07-25). "Identification made of 'Belle in Well' body found 38 years ago". WCHS. Archived from the original on 2019-07-27. Retrieved 2019-07-27.

- Moore, Jarrod; Clay, Jeff; Morris, Anna (2019-07-28). "'Belle in the Well' identified during news conference". WVAH. Archived from the original on 2019-07-29. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- Independent, MIKE JAMES The (29 July 2019). "DNA and genealogy solve mystery of long-dead woman's identity". The Independent Online. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Zhang, Sarah (2019-07-29). "She Was Found Strangled in a Well, and Now She Has a Name". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2019-07-30. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- "Human remains found in Mill Creek shed in 2015 identified". Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- "Police seek help after 'I-196 Jane' identified in 31-year-old cold case". mlive. November 26, 2019. Archived from the original on November 27, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- "NamUs UP # 2422". identifyus.org. National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. August 22, 2008. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- "Case File: 6UFKS". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- Volpenhein, Sarah (2018-07-24). "DNA testing might help identify Grate murder victim". Marion Star. Archived from the original on 2019-05-28. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "Kansas homicide victim identified more than 30 years after murder". www.kake.com. ABC. 23 December 2019. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- https://www.abc15.com/news/region-phoenix-metro/central-phoenix/phoenix-police-detectives-solve-22-year-old-cold-case Archived 2019-12-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- Griffith, Janelle (31 December 2019). "Human remains found in Idaho cave identified as outlaw who died over 100 years ago". NBC News. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "Case File 168UMWI". doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- "Barron Co John Doe 1982". DNA Doe Project. 7 Jan 2020. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- "74UFTX". www.doenetwork.org. The Doe Network. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Koski, Rudy (14 January 2020). "Williamson County Sheriff's Office identifies "Corona Girl" as 17-year-old from Sulphur Springs". FOX 7 Austin. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- "Georgetown: Mystery of identity of 1989 shooting victim solved". www.kwtx.com. Archived from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "Skull, torso found along Illinois River identified". KHQA. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- "Case File: 255UFOK". The Doe Network. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "NamUs UP # 4897". March 4, 2009. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Corbin, Cristina (February 28, 2014). "DNA profile of Oklahoma's murdered 'lime lady' emerges after three decades". Fox News. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Lime Lady Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Holeman, Heather (30 January 2020). "BREAKING: Officials identify Oklahoma's 'Lime Lady' at heart of 40-year-old cold case". KFOR.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- "Authorities identify 'Lime Lady,' victim of 40-year-old cold case murder in Oklahoma". KOCO. ABC. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Staff, azfamily com News. "Phoenix PD turns to genetic genealogy to ID victim in 2004 cold case". AZFamily. Archived from the original on 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- "Barron Co John Doe 2017". DNA Doe Project Cases. Archived from the original on 2020-05-25. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- DrydenWire (2020-06-23). "Barron County Homicide Victim Identified By Genetic Genealogy". DrydenWire.com. Archived from the original on 2020-06-25. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- "Kingsport PD identify remains found in Holston River 17 years ago as missing West Virginia man". WJHL-TV. August 6, 2020.

- Hudson, David (2019-05-16). "Can you help solve the mystery of Transgender Julie Doe?". Gay Star News. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- "Pillar Point Doe". DNA Doe Project. 1994. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Zhang, Sarah (23 December 2019). "Sleuths Are Haunted by the Cold Case of Julie Doe". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Schultz, Frank (2018-05-18). "New DNA method might identify body found in Rock County". GazetteXtra. Archived from the original on 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- "John Clinton Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- Montgomery, Austin (2019-02-28). "Body found in 1995 tentatively identified". Beloit Daily News, Michigan. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- Staff (2017-12-11). "Police: Woman pushed from truck, run over in Kensington". FOX 29 Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 2019-08-10. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- "NamUs #17475". www.namus.gov. 13 February 2018. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "NamUs #UP16790". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- "Nation River Lady". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- "NamUs #UP7632". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- LaVoice, Olivia (2018-10-25). "Kern County and Ventura County Jane Doe may be closer than ever to being identified". KGET. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP14243". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP11249". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "JANE DOE – ROCKLEDGE, FLORIDA". Federal Bureau of Investigation. 1980-10-11. Archived from the original on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- "Rockledge Jane Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP10222". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "NamUs #UP53955". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP4786". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- "Lee County John Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "NamUs #UP8272". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Fowler, Sam (2018-06-11). "Tom Green Sheriff's Office Releases Reconstruction of 1987 John Doe". San Angelo LIVE!. Archived from the original on 2019-05-28. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP4085". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP6107". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Ray, Karla (2018-12-17). "Julie Doe: Science provides new lead in 30-year-old Florida cold case". WFTV. Archived from the original on 2019-02-22. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP6030". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP4062". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Backus, Lisa (2018-10-22). "Cold case revisited: 1991 Jane Doe had gunshot wound to head". New Britain Herald. Archived from the original on 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- "NamUs #17475". www.namus.gov. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "Crime Tech Secures DNA Analysis Funds" (PDF). The Apache Junction/Gold Canyon News. XXII (35). 2018-08-27. p. A8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-23. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- "Apache Junction Jane Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP8224". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Staff (2020-01-14). "New DNA research finds possible link between 1993 Kenosha County John Doe victim and S.C. tribe". Kenosha County Government, Wisconsin. Archived from the original on 2020-03-05. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- "Kenosha John Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP7686". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP1944". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- DiPietrantonio, Stefano (2017-10-26). "John Doe has been a mystery since May 1997". Fox19 Now. Archived from the original on 2019-08-13. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- "Butler County John Doe 1997". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP8975". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "NamUs #UP15307". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP71". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "NamUs #UP13963". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP2004". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP8189". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP5281". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP8600". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP8724". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP61263". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP12017". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Czech, Ted (2018-12-06). "3D clay model revealed in the mysterious 'York County John Doe Case'". The York Daily Record. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- "West Manchester John Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP12886". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP13838". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Kings County Jane Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "NamUs #UP15135". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP15466". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "New Details Released About Unidentified Homicide Victim". St Tammany Parish Sheriff's Office. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Bakersfield Now staff (2019-02-05). "Human leg found at Lake Buena Vista does not belong to Bakersfield 3 woman". KBAK Bakersfield Now. Archived from the original on 2019-08-13. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- "Buena Vista Leg 2018". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP56927". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP11273". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP4547". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Jackson County John Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP8886". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP9888". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP12855". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "NamUs #UP86". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Volpenhein, Sarah. "Marion sheriff hopes to repeat success with 1989 John Doe cold case". Marion Star. Archived from the original on 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP7857". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP2681". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP3342". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP51512". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP9422". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Evangeline Parish Jane Doe 2018". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- "Hudson John Doe". DNA Doe Project. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP12533". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP6011". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP9927". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP53306". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP9541". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP9930". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Barn John Doe 2004". DNA Doe Project Cases. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP11445". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Unidentified Person / NamUs #UP5286". NAMUS. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "NamUs #UP59502". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- "NamUs #UP59504". www.namus.gov. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- "NamUs #UP2886". www.namus.gov. 13 December 2008. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- "NamUs #UP6599". www.namus.gov. 27 January 2010. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.