Conversion of non-Islamic places of worship into mosques

The conversion of non-Islamic places of worship into mosques occurred during the life of Muhammad and continued during subsequent Islamic conquests and under historical Muslim rule. As a result, Hindu temples, Buddhist temples, Christian churches, synagogues, and Zoroastrian fire temples were converted into mosques. The practice has led to conflicts and religious strife in various parts of the world.[2][3][4]

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic studies |

|---|

| Jurisprudence |

| Science |

| Arts |

| Architecture |

| Other topics |

.jpg)

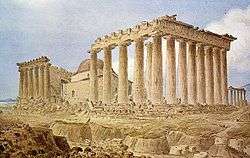

Several of such mosques in the areas of former Muslim rule have since been reconverted or become museums, such as the Parthenon in Greece, and numerous mosques in Spain such as Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba etc. Conversion of non-Islamic buildings into mosques influenced distinctive regional styles of Islamic architecture.

Qur'anic holy sites

Mecca

Muslims believe the mosque at Ka'ba[5] was rebuilt and used for monotheistic worship since the time of Ibrahim and Ismail.

Before Muhammad, the Kaʿba and Mecca (referred to as Bakkah in the Quran), were revered as a sacred sanctuary and was a site of pilgrimage.[6] Some identify it with the Biblical "valley of Baca" from Psalms 84 (Hebrew: בָּכָא).[7][8] At the time of Muhammad (AD 570–632), his tribe the Quraysh was in charge of the Kaʿaba, which was at that time a shrine containing hundreds of idols representing Arabian tribal gods and other religious figures. Muhammad earned the enmity of his tribe by claiming the shrine for the new religion of Islam, which Muhammad claimed to be the religion (monotheism) of Adam and Abraham, that he preached. He wanted the Kaʿaba to be dedicated to the worship of the one God alone, and all the idols were evicted. The Black Stone (al-Hajar-ul-Aswad) at the Kaʿaba was a special object of veneration at the site. According to tradition the text of seven or ten especially honoured poems were suspended around the Kaʿaba.[9]

Jerusalem

Mosques were regularly established on the places of Jewish or Christian sanctuaries associated with Koranic personalities who were also mentioned in the Bible.

Upon the capture of Jerusalem, it is commonly reported that Umar, the Commander of the Faithful, refused to pray in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre[10] for fear that later Muslims would then convert it into a mosque in spite of a treaty guaranteeing its status.[11] The architecturally similar Dome of the Rock was built on the Temple Mount, which was an abandoned and disused area in the 7th century but which had previously been the site of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, the most sacred site in Judaism.[12] Umar initially built there a small prayer house which laid the foundation for the later construction of the Al-Aqsa mosque by the Umayyads.

Elsewhere

The mosque of Job in Al-Shaykh Saad, Syria, was previously a church of Job.[13]

The Herodian shrine of the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, the second most holy site in Judaism, was converted into a church during the Crusades before being turned into a mosque in 1266 and henceforth banned to Jews and Christians. Part of it was restored as a synagogue by Israel after 1967.

Hindu, Jain and Buddhist temples

The destruction of Hindu temples in India during the Islamic conquest of India occurred from the beginning of Muslim conquest until the end of the Mughal Empire throughout the Indian subcontinent.

Bindu Madhav (Nand Madho) Temple

The Alamgir Mosque in Varanasi was constructed by Mughal Emperor Aurnagzeb built atop the ancient 100 ft high Bindu Madhav (Nand Madho) Temple after its destruction in 1682.[14]

Kashi Vishwanath Temple

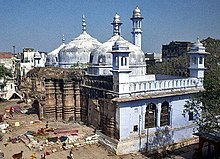

The original Kashi Vishwanath Temple was demolished by Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal emperor who constructed the Gyanvapi Mosque atop the original Hindu temple. Kashi Vishwanath was among the most renowned Hindu temples of India. Even today the pillars and the structure of the original temple can be clearly seen.

Aurangzeb's demolition of the temple was motivated by the rebellion of local zamindars (landowners) associated with the temple, some of whom may have facilitated the escape of the Maratha king Shivaji. Jai Singh I, the grandson of the temple's builder Raja Man Singh, was widely believed to have facilitated Shivaji's escape from Agra.[15] The temple's demolition was intended as a warning to the anti-Mughal factions and Hindu religious leaders in the city.[16]

As described by Jadunath Sarkar, on 9 April 1669, Aurangzeb issued a general order “to demolish all the schools and temples of the infidels and to put down their religious teaching and practices.” His destroying hand now fell on the great shrines that commanded the veneration of the Hindus all over India—such as the second temple of Somnath, the Vishwanath temple of Benares and the Keshav Rai temple of Mathura.[17]

Menara Kudus Mosque

One of Indonesia's most famous mosques, Menara Kudus has retained much of its former Hindu character.

Ram Janmabhoomi

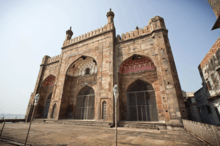

Ram Janmabhoomi refers to a tract of land in the North Indian city of Ayodhya which is the birthplace of Lord Rama according to the Hindu philosophy. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), after conducting excavations at the site, filed a report which stated that a temple-like structure stood at the site before the arrival of the first ruler of the Mughal Empire, Babur, who constructed the Babri Masjid ("Mosque of Babur") at the site. However, it is important to clarify that, after scientific testing carried out by ASI's team, "it was claimed that there were remains of an ancient Hindu temple under the disputed structure." and said it "was not an Islamic structure" but, could not establish whether a temple was demolished to build a Mosque.[19] From 1528 to 1992 this was the site of the Babri Mosque (Babri Masjid). The mosque was constructed in 1527 on the orders of Babur and named after him. Before the 1940s, the mosque was also called Masjid-i-Janmasthan, translation: ("mosque of the birthplace"). The Babri Mosque was one of the largest mosques in Uttar Pradesh, a state in India with some 31 million Muslims.

Critics of the ASI state that the "presence of animal bones throughout as well as of the use of 'surkhi' and lime mortar" that was found by ASI are all characteristic of Muslim presence, which they claim "rule out the possibility of a Hindu temple having been there beneath the mosque".[20]

The mosque was razed on 6 December 1992 by a mob of some 150,000 Hindus supported by the Hindu organisation Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP),[3][4] after a political rally developed into a riot[21] despite a commitment to the Indian Supreme Court by the rally organisers that the mosque would not be harmed.[22] The Sangh Parivaar, along with VHP and the Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP), sought to erect a temple dedicated to Rama at this site. The 1986 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica stated that "Rama's birthplace is marked by a mosque, erected by the Moghul emperor Babar in 1528 on the site claimed of an earlier temple".[23] Numerous petitions by Hindus to the courts resulted in Hindu worshippers of Rama gaining access to the site.

On 30 September 2010, Allahabad High Court ruled that the 2.7 acres disputed land in Ayodhya, on which the Babri Masjid stood before it was demolished on 6 December 1992, will be divided into three parts: the site of the Ramlala idol to Lord Ram, Nirmohi Akhara gets Sita Rasoi and Ram Chabutara, Sunni Wakf Board gets a third.

In 9 November 2019, the Supreme Court of India delivered a judgement which gave the entire 2.77 acres of land to the Hindu trust to build the temple. Muslim parties were given an alternate 5 acres of land inside Ayodha city limits to build a mosque.[24]

Other references

An inscription at the Quwwat Al-Islam Mosque adjacent to Qutb Minar in Delhi states:

"This Jamii Masjid built in the months of the year 587 (hijri) by the Amir, the great, the glorious commander of the Army, Qutb-ud-daula wad-din, the amir-ul-umara Aibeg, the slave of the Sultan, may God strengthen his helpers! The materials of 27 idol temples, on each of which 2,000,000 Deliwal coins had been spent were used in the (construction of) this mosque."[25]

An inscription of 1462 A.D.at Jami Masjid at Malan, in Banaskantha District of Gujarat states:

The Jami Masjid was built by Khan-I-Azam Ulugh Khan. He eradicated the idolatrous houses and mine of infidelity, along with the idols with the edge of the sword, and made ready this edifice.He made its walls and doors out of the idols; the back of every stone became the place for prostration of the believer.[26]

Sikh Gurdwaras

Gurdwara Lal Khoohi in Lahore, Pakistan was a Sikh Gurdwara which was converted to muslim shrine.[27][28]

Zoroastrian fire temples

After the Islamic conquest of Persia, Zoroastrian fire temples, with their four axial arch openings, were usually turned into mosques simply by setting a mihrab (prayer niche) on the place of the arch nearest to qibla (the direction of Mecca). This practice is described by numerous Muslim sources; however, the archaeological evidence confirming it is still scarce. Zoroastrian temples converted into mosques in such a manner could be found in Bukhara, as well as in and near Istakhr and other Iranian cities,[13] such as: Tarikhaneh Temple, Jameh Mosque of Qazvin, Heidarieh Mosque of Qazvin, Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, Jameh Mosque of Kashan, Jameh Mosque of Ardestan, Jameh Mosque of Yazd, Jameh Mosque of Borujerd, Great Mosque of Herat as well as Bibi Shahr Banu Shrine near Tehran.

Conversion of church buildings to mosques

Albania

The Catholic church of Saint Nicholas (Shën Nikollë) was turned into a mosque. After being destroyed in the Communist 1968 anti-religious campaign, the site was turned into an open air mausoleum.

Bosnia and Hercegovina

The Fethija Mosque (since 1592) of Bihać was a Catholic church devoted to Saint Anthony of Padua (1266).

Turkey

Before the 20th century

Istanbul

Following the Ottoman conquest of Anatolia, virtually all of the churches of Istanbul were converted into mosques except the Church of St. Mary of the Mongols.[29]

- Hagia Sophia (from the Greek: Ἁγία Σοφία, "Holy Wisdom"; Latin: Sancta Sophia or Sancta Sapientia; Turkish: Ayasofya) was the cathedral of Constantinople in the state church of the Roman Empire and the seat of the Eastern Orthodox Church's Patriarchate. After 1453 it became a mosque, and since 1931 it has been a museum in Istanbul, Turkey. From the date of its dedication in 360 until 1453, it served as the Orthodox cathedral of the imperial capital, except between 1204 and 1261, when it became the Roman Catholic cathedral under the Latin Patriarch of Constantinople of the Western Crusader-established Latin Empire. In 1453, Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman Turks under Sultan Mehmed II, who subsequently ordered the building converted into a mosque.[30] The bells, altar, iconostasis, ambo and sacrificial vessels were removed and many of the mosaics were plastered over. Islamic features – such as the mihrab, minbar, and four minarets – were added while in the possession of the Ottomans. The building was a mosque from 29 May 1453 until 1931, when it was secularised. It was opened as a museum on 1 February 1935.[31] On July 10, 2020, the decision of the Council of Ministers to transform it into a museum was canceled by Council of State and the Turkish President Erdoğan signed a decree annulling the Hagia Sophia's museum status, reverting it to a mosque.[32][33]

- The Church of the Holy Apostles became the cathedral church and seat of the patriarchate for three years after the Fall of Constantinople, as Hagia Sophia became the city's Jama masjid. The Justinianic church was already in disrepair and in 1461 it was demolished and the Fatih Mosque was erected in its place.

- The Church of the Pantocrator, a church favoured for imperial burials in the latter Byzantine Empire, became the Zeyrek Mosque.

- The Church of SS Sergius and Bacchus, a church built by Justinian I, became a mosque dubbed the Little Hagia Sophia.

- The Church of Saint Andrew in Krisei, became the Koca Mustafa Pasha Mosque.

- The Church of Saint Thekla of the Palace of Blachernae, became the Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque.

- The nunnery of Saint Theodosia, became the Gül Mosque.

- The Chora Church became the Kariye Mosque.

- The Monastery of Stoudios became the İmrahor Mosque.

- The Church of Saint John the Forerunner by-the-Dome became the Hirami Ahmet Pasha Mosque.

- The Church of Myrelaion became the Bodrum Mosque.

- The Catholic Church of Saint Paul became the Arap Mosque.

- The Lips Monastery became the Fenari Isa Mosque.

- The Monastery of Christ Pantepoptes became the Eski Imaret Mosque.

- The Church of Theotokos Kyriotissa became the Kalenderhane Mosque.

- The Church of Hagios Theodoros at Vefa became the Church-Mosque of Vefa.

- The Monastery of Manuel became the Kefeli Mosque.

- The Monastery of Gastria became the Sancaktar Hayrettin Mosque.

- The Church of Saint Mary of Constantinople became the Odalar Mosque.

- The Pammakaristos Church became the Fethiye Mosque.

- The Toklu Dede Mosque was an Eastern Orthodox church of unknown dedication.

- The monastery of the Holy Martyrs Menodora, Metrodora, and Nymphodora became the Manastır Mosque.

Rest of Turkey

Elsewhere in Turkey numerous churches were converted into mosques, including:

Orthodox

- Hagia Sophia Church in Nicaea (İznik)

- Hagia Sophia Church in Trebizond (Trabzon)

- Panagia Chrysokephalos Church, became the Fatih Mosque in Trabzon (Trabzon)

- Nakip Mosque was a Byzantine church. (Trabzon)

- Hagios Eugenios Church, became the New Friday Mosque (Trabzon)

- Saint Paul Cathedral, became the Tarsus Old Mosque (Tarsus)

- Church of Virgin Mary, became the Kesik Minare (Antalya)

- Church of Christ and Saint Stephen, became the Fatih Mosque in Tirilye (Tirilye)

Armenian Apostolic

- Cathedral of Kars

- Cathedral of Ani

- Liberation Mosque, ex St Mary's Church Cathedral, Gaziantep

20th century and after

In addition, after the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), some of the Greek Orthodox churches in Turkey were converted into mosques. In 2015, Turkey decided to renovate the ruined Hagia Sophia church in Enez, dating back to the 12th century, as a mosque despite former statements made about the possibility of restoring it as a museum.[34] As of 2020, four Byzantine church museums converted to mosques under Erdogan's rule (including the Haghia Sophia in İznik (2011),[35] the Chora Church in Istanbul (2019)[36] and the Haghia Sophia in Istanbul (2020)).[37]

Cyprus

Following the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus, a number of Christian churches were converted into mosques. A relatively significant surge in church-mosque conversion followed the 1974 Turkish Invasion of Cyprus. Many of the Orthodox churches in Northern Cyprus have been converted, and many are still in the process of becoming mosques.

- St. Nicholas Cathedral in Famagusta, Cyprus was converted by the Ottoman Turks into Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque in 1571; remains in use as mosque today.

- St. Sophia Cathedral in Nicosia, Cyprus was converted by the Ottoman Turks into the Selimiye Mosque, Nicosia; remains in use as mosque today.

France

During the Ottoman wintering in Toulon (1543–44), the Toulon Cathedral was temporarily used as a mosque for the 30,000 members of the crew of the Ottoman fleet.

Greece

Numerous orthodox churches were converted to mosques during the Ottoman period in Greece. Among them:

- The Church of the Acheiropoietos (Eski Mosque), the Church of Hosios David (Suluca or Murad Mosque), the Church of Prophet Elijah (Saraylı Mosque), the Church of Saint Catherine (Yakup Pasha Mosque), the Church of Saint Panteleimon (Ishakiye Mosque), the Church of Holy Apostles (Soğuksu Mosque), the Church of Hagios Demetrios (Kasımiye Mosque), the Rotonda of Galerius (Mosque of Suleyman Hortaji Effendi) in Thessaloniki.

- The Cathedral church of Veria (Hünkar Mosque) and the Church of Saint Paul in Veria (Medrese Mosque).

- The Church of Saint John in Ioannina, destroyed by the Ottomans and the Aslan Pasha Mosque was built in its place.

- The Theotokos Kosmosoteira monastery in Feres was converted into a mosque in the mid-14th century.

- Parthenon in Athens: Some time before the close of the fifteenth century, the Parthenon became a mosque. Before that the Parthenon had been a Greek Orthodox church.

- The Fethiye Mosque in Athens was built on top of a Byzantine basilica. It is currently an exhibition centre.

.jpg)

Hungary

Following the Ottoman conquest of the Kingdom of Hungary, a number of Christian churches were converted into mosques. Those that survived the era of Ottoman rule, were later reconverted into churches after the Great Turkish War.

- Church of Our Lady of Buda, converted into Eski Djami immediately after the capture of Buda in 1541, reconverted in 1686.

- Church of Mary Magdalene, Buda, converted into Fethiye Djami c. 1602, reconverted in 1686.

- The Franciscan Church of St John the Baptist in Buda, converted into Pasha Djami, destroyed in 1686.

Lebanon

- Al-Omari Grand Mosque in Beirut, Lebanon; built as the Church of St. John the Baptist by the Knights Hospitaller; converted to mosque in 1291.

Morocco

- Grand Mosque of Tangier; built as Church

Spain

A Catholic Christian church dedicated to Saint Vincent of Lérins, was built by the Visigoths in Córdoba; during the reign of Abd al-Rahman I, it was converted into a mosque.[38][39][40] In the time of the Reconquista, Christian rule was reestablished and the building became a church once again, the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption.[38][39][40]

Syria

- Umayyad Mosque in Damascus; built on the site of a Christian basilica dedicated to John the Baptist (Yahya), which was earlier, a Roman Pagan temple of Jupiter.

Umayyad Mosque mosque was built on the site of a Christian basilica dedicated to John the Baptist, which was earlier a Temple of Jupiter converted into a cathedral by the Roman emperor Theodosius I

Umayyad Mosque mosque was built on the site of a Christian basilica dedicated to John the Baptist, which was earlier a Temple of Jupiter converted into a cathedral by the Roman emperor Theodosius I - Great Mosque of al-Nuri in Homs; initially a pagan temple for the sun god ("El-Gabal"), then converted into a church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist

- Great Mosque of Hama; a temple to worship the Roman god Jupiter, later it became a church during the Byzantine era

- Great Mosque of Aleppo; the agora of the Hellenistic period, which later became the garden for the Cathedral of Saint Helena

Post-Colonial North Africa

A number of North African cathedrals and churches were converted into mosques in the mid-20th century

- St. Philip Cathedral in Algiers, Algeria (originally a mosque, converted to a church in 1845, reconverted to the Ketchaoua Mosque in 1962)

- Cathédrale Notre-Dame des Sept-Douleurs in Constantine, Algeria

- Tripoli Cathedral in Tripoli, Libya (converted to Maidan al Jazair Square Mosque)

Iraq

The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria converted a number of Christian churches into mosques after they occupied Mosul in 2014. The churches were restored into its original functions after Mosul was liberated in 2017.[41]

- Syrian Orthodox Church of St. Ephraim in Mosul, Iraq; converted to the Mosque of the Mujahideen

- Chaldean Church of St. Joseph in Mosul, Iraq

Israel

- Church of Saint James Intercisus in the Old City of Jerusalem, transformed into Al-Yaqoubi Mosque

- Templum Domini (Dome of the Ascension, Dome of the Rock)

- Tomb of the Patriarchs

- Tombs of Nathan and Gad in Halhoul, transformed into Mosque of Prophet Yunus.[43][44]

Elsewhere

In part of Europe and North America with significant Muslim populations,[46][47] some church buildings and buildings of other religious congregations that have fallen into disuse have been converted into mosques following a sale of the property. In the United States examples include two Catholic churches in Detroit.[48]

United Kingdom

- In London, England the Brick Lane Mosque has previously served as an Orthodox Jewish synagogue.[49]

United States

- Burlington Masjid[50] in Burlington, NC located in a former UCC church.

- Bosnian Islamic Association of Utica[51] in Utica, NY located in a former Methodist church.

- Masjid Isa Ibn Maryam[52] ("The Mosque of Jesus, son of Mary" in English) in Syracuse, NY located in a former Catholic church.

- Masjid 'Eesa ibn Maryam (NYCMC)[53] in Hollis, Queens, New York, NY located in a former ELCA-Lutheran church.[54]

- Brooklyn Moslem Mosque Inc.[55] in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York, NY located in a building that formerly held (at various times) a greenhouse, a Methodist Episcopal church, an Evangelical church, and a Community Board meeting-space.[56] Also noteworthy, said masjid's community itself is the oldest continuously existing Muslim congregation in America (since its founding in 1907), although they did not move into the aforementioned building until the 1920s. (This makes them not the oldest congregation, as they were founded after the Albanian masjid in Maine, and not the oldest purpose built masjid still standing or otherwise due to the Mother Mosque in Cedar Rapids and the now rebuilt Ross, North Dakota masjid.

- Altoona Masjid in Altoona, WI is located in a building that initially housed the Bethlehem Lutheran Church (which is affiliated to the Missouri-Synod branch) from 1908–1960,[57] and the Harvestime Church (which is a Pentecostal Church affiliated to the Assemblies of God branch) from 1960–1992.[58] Altoona Masjid has been in the building since 1992.

- Masjid Al-Jamia[59] of Philadelphia, PA is located in what was initially a movie theater called the "Commodore Theatre,"[60] which operated from 1928 to the 1950s, before being re-purposed in the 1960s as a performing arts theater called "43rd Street Theatre." Between the 1960s and 1973, the building hosted the Pentecostal "Miracle Revival Tabernacle Church." In 1973, students from the University of Pennsylvania's Muslim Student Association, along with NAIF, founded Masjid Al-Jamia in the building.

- The Arabic Jumaa Mosque/Tousef Mosque/Palestinian Cultural Center for Peace in Boston, MA was originally a Congregationalist Church called the Allston Congregational Church.

- Baitul Mamoor Jam-E-Masjid in Buffalo, NY is located in a former Catholic Church that was called "Holy Mother of Rosary Polish National Catholic Church,[61]" of which was built in 1904 and was used as a church until 1994.[62]

- Masjid Zakariya in Buffalo, NY is located in a former Catholic Church that was called "Saint Joachim's Roman Catholic Church," which was built in 1953 and was used as a church until 1993.[63]

- Jami' Masjid in Buffalo, NY is located in a former Catholic church that was called "Queen of Peace Roman Catholic Church," which was sold in 2009.[61]

- In Catasauqua, PA as of 2019, a new masjid is being moved into the former St. Paul's Evangelical Lutheran Church[64]

- The Islamic Society of Greater Harrisburg in Steelton, PA is located in a former Catholic church that was called "St. James Catholic Church," which was sold to ISGH sometime after the 1980s.[65] While ISGH was founded in the early 1970s, they were housed at various times in community members' homes, and behind Harrisburg East Mall (now just "Harrisburg Mall") in a former Christian Sunday school annex building, both prior to being moved into the former St. James church building on Front Street. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Harrisburg picked ISGH as who they would sell the building to, despite a low selling price, quote, "so that the facility would continue as a place of worship[,]"[65] instead of being torn down or used for a non-religious function. Notably, when moving into the building, the Harrisburg Diocese helped "replace the stained glass windows of the Stations of the Cross with stained glass panels of some of the ninety-nine names of God in Arabic."[65]

- Mosque Maryam in Chicago, IL is located in a former Greek Orthodox church and has been acting as the headquarters for the Nation of Islam since 1972.[66]

Germany

- Neuapostolische Kirche in Berlin-Tempelhof[67]

- Methodist Church in Mönchengladbach[68]

- Evangelische Notkirche Johannes, Kielstraße, Dortmund, now Merkez Camii (DITIB)[69]

- Kapernaumkirche (Hamburg-Horn)[70]

Influence on Islamic architecture

Conversion of non-Islamic religious buildings into mosques during the first centuries of Islam played a major role in the development of Islamic architectural styles. Distinct regional styles of mosque design, which have come to be known by such names as Arab, Persian, Andalusian, and others, commonly reflected the external and internal stylistic elements of churches and other temples characteristic for that region.[71]

See also

- Buddhas of Bamyan

- Christianized sites

- Conversion of mosques into non-Islamic places of worship

- Islam and other religions

- List of destroyed heritage

- Meštrović Pavilion, a museum in Croatia re-arranged as a mosque in 1941-1945

References

- name="Reginald_1829"https://archive.org/stream/narrativeofjourn01hebe#page/258/mode/2up

- https://greekcitytimes.com/2019/04/29/historical-st-nicholas-cathedral-in-cyprus-turned-into-a-mosque-under-turkish-occupation/?amp

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Uproar over India mosque report: Inquiry into Babri mosque's demolition in 1992 Archived 31 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine Al-Jazeera English – 24 November 2009

- "Surah Al-Baqarah [2:125]". Surah Al-Baqarah [2:125]. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Britannica 2002 Deluxe Edition CD-ROM, "Ka'bah."

- Daniel C. Peterson (2007). Muhammad, prophet of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-8028-0754-0.

- Psalms 84:6, King James Version

- Amnon Shiloah (2001). Music in the World of Islam: A Socio-Cultural Study. Wayne State University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780814329702.

- He was touring the Church and prayer time came around and he requested to be shown to a place where he may pray and the Patriarch said "Here".

- Adrian Fortescue, "The Orthodox Eastern Church", Gorgias Press LLC, 1 December 2001, pg. 28 ISBN 0-9715986-1-4

- Orlin, Eric (19 November 2015). Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions. ISBN 9781134625598. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Hillenbrand, R. "Masdjid. I. In the central Islamic lands". In P.J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- Crowther, Geoff; Raj, Prakash A.; Wheeler, Tony (1984). India, a Travel Survival Kit. Lonely Planet.

- Truschke, Audrey (16 May 2017). Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India's Most Controversial King. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503602595.

- Catherine B. Asher (24 September 1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 278–279. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1930). A Short history of Aurangzib. Calcutta: M.C Sarkar & Sons. pp. 155–156.

- Schoppert, P., Damais, S., Java Style, 1997, Didier Millet, Paris, p. 207, ISBN 962-593-232-1

- "Ayodhya verdict: The ASI findings Supreme Court spoke about in its judgment". India Today. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Ayodhya verdict yet another blow to secularism: Sahmat Archived 6 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu, 3 October 2010

- Babri mosque demolition case hearing today. Yahoo News – 18 September 2007

- Tearing down the Babri Masjid – Eye Witness BBC's Mark Tully Archived 27 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine BBC – Thursday, 5 December 2002, 19:05 GMT

- 15th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, 1986, entry "Ayodhya", Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.

- "Disputed Ayodhya site to be divided into 3 parts- TIMESNOW.tv – Latest Breaking News, Big News Stories, News Videos". Timesnow.Tv. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- Epigraphia Indo Moslemica, 1911–12, p. 13.

- Epigraphia Indica-Arabic and Persian Supplement, 1963, Pp. 26–29

- "Lahore's historical gurdwara now a Muslim shrine". The Tribune. 14 June 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Sheikh, Majid (17 February 2019). "HARKING BACK: Fateful route of a great Guru as he walked to his death". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Mamboury (1953), p. 221.

- "Archnet". Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- Magdalino, Paul; et al. "Istanbul: Buildings, Hagia Sophia". Grove Art Online. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/turkiye/ayasofyayi-camiden-muzeye-donusturen-bakanlar-kurulu-kararina-iptal-/1906077

- "Hagia Sophia: Turkey turns iconic Istanbul museum into mosque". BBC. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Historic Hagia Sophia in a Turkish province to be re-opened as mosque

- Letsch, Constanze (2 December 2011). "Turkey: Mystery Surrounds Decision to Turn Byzantine Church Museum into a Mosque". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- YACKLEY, AYLA JEAN (2 July 2020). "From museum to mosque? Turkish court to rule on Hagia Sophia's fate". politico.eu. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Gall, Carlotta (15 July 2020). "Erdogan Signs Decree Allowing Hagia Sophia to Be Used as a Mosque Again". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Christys, Ann (2017). "The meaning of topography in Umayyad Cordoba". In Lester, Anne E. (ed.). Cities, Texts and Social Networks, 400–1500. Routledge.

It is a commonplace of the history of Córdoba that in their early years in the city, the Muslims shared with the Christians the church of S. Vicente, until ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I bought the Christians out and used the site to build the Great Mosque. It was a pivotal moment in the history of Córdoba, which later historians may have emphasised by drawing a parallel between Córdoba and another Umayyad capital, Damascus. The first reference to the Muslims’ sharing the church was by Ibn Idhārī in the fourteenth century, citing the tenth-century historian al-Rāzī. It could be a version of a similar story referring to the Great Mosque in Damascus, which may itself have been written long after the Mosque was built. It is a story that meant something in the tenth-century context, a clear statement of the Muslim appropriation of Visigothic Córdoba.

- Guia, Aitana (1 July 2014). The Muslim Struggle for Civil Rights in Spain, 1985–2010: Promoting Democracy Through Islamic Engagement. Sussex Academic Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-84519581-6.

It was originally a small temple of Christian Visigoth origin. Under Umayyad reign in Spain (711–1031 CE), it was expanded and made into a mosque, which it would remain for eight centuries. During the Christian reconquest of Al-Andalus, Christians captured the mosque and consecrated it as a Catholic church.

- Armstrong, Ian (2013). Spain and Portugal. Avalon Travel Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61237031-6.

On this site originally stood the Visigoths' Christian Church of San Vicente, but when the Moors came to town in 758 CE they knocked it down and constructed a mosque in its place. When Córdoba fell once again to the Christians, King Ferdinand II and his successors set about Christianizing the structure, most dramatically adding the bright pearly white Renaissance nave where mass is held every morning.

- "Iraq: Daesh have robbed and demolished every church". Independent Catholic News. 6 March 2018. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Tristram, Henry Baker (1865). The land of Israel : a journal of travels in Palestine, undertaken with special reference to its physical character. London: London Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 394.

The design is unique and patriarchal in its magnificent simplicity. One can scarcely tolerate the theory of some architectural writers, that this enclosure is of a period later than the Jewish. It would have been strange if any of the Herodian princes should here alone have raised, at enormous cost, a building utterly differing from the countless products of their architectural passion and Roman taste with which the land is strewn.

- "For first time in 18 years, Jews pray at biblical tombs in Palestinian village". Times of Israel. AFP. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Adler, Elkan Nathan (4 April 2014). Jewish Travellers. Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-134-28606-5.

"From there we reached Halhul, a place mentioned by Joshua. Here there are a certain number of Jews. They take travelers to see an ancient sepulchral monument attributed to Gad the Seer." — Isaac ben Joseph ibn Cehlo, 1334

- "The Hague – Jewish Cultural Quarter". jck.nl. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

Since 1981 the synagogue building at Wagenstraat is owned by the Turkish community and is now a mosque.

- Perlez, Jane (2 April 2007). "Old Church Becomes Mosque in Uneasy Britain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Applebome, Peter (18 August 2010). "Utica Welcomes a New Mosque Replacing an Old Church". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- Karam, Rebecca (4 August 2017). "Rust Belt Revitalization, Immigration, and Islam: Toward a Better Understanding of Mosques in Declining Urban Neighborhoods". City & Community. American Sociological Association. 16 (3): 257–62. doi:10.1111/cico.12244.

- "Rav and history – Machzike Hadath". Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Abernethy, Michael D. "Bridging faith: Welcomed by Christian church, Muslim mosque comes to Burlington". The Times-News. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- "How crumbling church became celebrated Utica Mosque (photos)". New York Upstate. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- "From church to mosque: Syracuse Islamic group cuts crosses, tries to connect to neighborhood". Syracuse. 16 August 2015. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- "NYCMC Expansion Project". NYCMC Expansion Project. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- "Holy Trinity Lutheran Church – Hollis (Queens), N.Y." www.nycago.org. Archived from the original on 31 May 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Schuessler, Ryan (12 December 2016). "They gave her the keys to the mosque – and now she wants to open its doors to the neighborhood". PRI. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Siddiqui, Zuha (26 December 2018). "America's Oldest Surviving Mosque Is in Williamsburg". Bedford + Bowery. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "History – Harvestime Church – Building Lives for Life Change". Harvestime Church. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "History". Altoona Masjid ISNW. 12 January 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "Masjid Al-Jamia: The History of Penn's Muslim Students Association and the Mosque in West Philadelphia · Masjid Al-Jamia: Penn's Muslim Students Association and the Mosque in West Philadelphia · Here and Over There: Penn, Philadelphia, and the Middle East". pennds.org. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Commodore Theatre in Philadelphia, PA – Cinema Treasures". cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Krishna, Ashima. "A new solution for America's empty churches: A change of faith". The Conversation. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "James Napora". buffaloah.com. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "James Napora". buffaloah.com. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Wojcik, Sarah M. "Catasauqua congregation bids farewell to 167-year-old church, which will become Islamic worship center: 'This will still be a place of worship'". mcall.com. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "Islamic Society of Greater Harrisburg (ISGH) | The Pluralism Project". pluralism.org. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- David Lepeska (9 April 2011). "Farrakhan Using Libyan Crisis to Bolster His Nation of Islam". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Gotteshäuser: Aus Kirchen werden Moscheen Archived 28 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Tagesspiegel, 5. Oktober 2007.

- Marion Menne: "Wirbel um Kirchen-Verkauf". Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link), WDR, 25. Juni 2012.

- alexpressedo (27 July 2014). "Nordstadt: Deutschlands erste Moschee wird aufgewertet". Nordstadtblogger (in German). Retrieved 20 July 2020.

In 1973 an evangelical parish hall was turned into a mosque.

- "Eröffnungsfeier in Hamburg - Von der Kirche zur Moschee". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 20 July 2020.

Modern chandeliers flood the new Al-Nour mosque with its bright, warm light, on top of the gallery there are characters of a Koran quote across the entire width of the former Evangelical Capernaum church.

- Patrick D. Gaffney (2004). "Masjid". In Richard C. Martin (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference.