Common quail

The common quail (Coturnix coturnix), or European quail, is a small ground-nesting game bird in the pheasant family Phasianidae. Coturnix is the Latin for this species.[2]

| Common quail | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Coturnix |

| Species: | C. coturnix |

| Binomial name | |

| Coturnix coturnix | |

| |

| Range of C. coturnix Breeding Resident Non-breeding Possible extinct & Introduced Extant & Introduced (resident) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

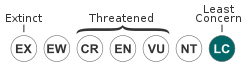

With its characteristic call of "wet my lips", this species of quail is more often heard than seen. It is widespread in Europe and North Africa, and is categorised by the IUCN as "least concern". It should not be confused with the Japanese quail, Coturnix japonica, native to Asia, which, although visually similar, has a very distinct call. Like the Japanese quail, common quails are sometimes kept as poultry.

Description

It is a small, round bird, essentially streaked brown with a white eyestripe, and, in the male, a white chin. As befits its migratory nature, it has long wings, unlike the typically short-winged gamebirds. It measures roughly 18.0–21.9 cm (7.1–8.62 in) and weighs 91–131 g (3.2–4.62 oz).[3]

Habits

This is a terrestrial species, feeding on seeds and insects on the ground. It is notoriously difficult to see, keeping hidden in crops, and reluctant to fly, preferring to creep away instead. Even when flushed, it keeps low and soon drops back into cover. Often the only indication of its presence is the distinctive "wet-my-lips" repetitive song of the male. The call is uttered mostly in the mornings, evenings and sometimes at night. It is a strongly migratory bird, unlike most game birds.

Breeding

Upon attaining an age of 6–8 weeks, this quail breeds on open arable farmland and grassland of the west Palearctic, including most of Europe, laying 6-12 eggs in a ground nest. The eggs take from 16–18 days to hatch.

Subspecies

This species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Tetrao coturnix.[4] The Eurasian subspecies, C. c. coturnix, overwinters southwards in Africa's Sahel and India. The populations on Madeira and the Canary Islands belong to the nominate subspecies. The African subspecies, C. c. africana, described by Temminck and Schlegel in 1849, is known as the African quail. It overwinters in Africa, some moving northwards from South Africa. The common quails of Madagascar and the Comoros belong to the same African subspecies, although those found around Ethiopia make up a different subspecies, the Abyssinian quail, C. c. erlangeri (Zedlitz, 1912). The fairly numerous[5] population of the Cape Verde islands belong to a separate subspecies, C. c. inopinata, (described by Hartert in 1917), while those on the Azores belong to subspecies C. c. conturbans (Hartert, 1920).

Utilization

It is heavily hunted as game on passage through the Mediterranean area. This species over recent years has seen an increase in its propagation in the United States and Europe. However, most of this increase is with hobbyists.

In 1537, Queen Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII, then pregnant with the future King Edward VI, developed an insatiable craving for quail, and courtiers and diplomats abroad were ordered to find sufficient supplies for the Queen.

Poisoning

If they have eaten certain plants, although which plants is still in debate, the meat from quail can be poisonous, with one in four who consume poisonous flesh becoming ill with coturnism, which is characterized by muscle soreness, and which may lead to kidney failure.[6][7][8]

Gallery

.jpg) Female

Female ID composite

ID composite Eggs - MHNT

Eggs - MHNT- Eggs, Collection Museum Wiesbaden

Head of nominate subspecies

Head of nominate subspecies Head of Coturnix coturnix africana

Head of Coturnix coturnix africana

See also

- Quails in cookery

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Coturnix coturnix". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Hume, A.O.; Marshall, C.H.T. (1880). Game Birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon. Volume II. Calcutta: A.O. Hume and C.H.T. Marshall. p. 148.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 161.

T. pedibus nudis, corpore griseo-maculato, superciliís albis, rectricibus margine lunulaque ferruginea.

- E. Krabbe, 2003

- Korkmaz I, Kukul Güven FM, Eren SH, Dogan Z (October 2008). "Quail Consumption Can Be Harmful". J Emerg Med. 41 (5): 499–502. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.03.045. PMID 18963719.

- Tsironi M, Andriopoulos P, Xamodraka E, et al. (August 2004). "The patient with rhabdomyolysis: have you considered quail poisoning?". CMAJ. 171 (4): 325–6. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1031256. PMC 509041. PMID 15313988.

- Ouzounellis T (16 February 1970). "Some notes on quail poisoning". JAMA. 211 (7): 1186–7. doi:10.1001/jama.1970.03170070056017. PMID 4904256.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coturnix coturnix. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Coturnix coturnix |

- Common quail species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- Common quail photos at Oiseaux

- Identification guide (PDF; 3.4 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- BirdLife species factsheet for Coturnix coturnix

- "Coturnix coturnix". Avibase.

- "Common quail media". Internet Bird Collection.

- European Quail photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Coturnix coturnix at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Common quail on Xeno-canto.