Chanin Building

The Chanin Building, also known as 122 East 42nd Street, is a 56-story office skyscraper in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is located on the southwest corner of 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue, near Grand Central Terminal to the north and adjacent to 110 East 42nd Street to the west. The building is named for Irwin S. Chanin, its developer.

Chanin Building | |

(2003) | |

| |

| Location | 122 East 42nd Street Manhattan, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′04″N 73°58′36″W |

| Built | 1927–1929 |

| Architect | Sloan & Robertson Rene Chambellan |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| NRHP reference No. | 80002676[1] |

| NYCL No. | 0993 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 23, 1980 |

| Designated NYCL | November 14, 1978 |

The structure was designed by Sloan & Robertson in the Art Deco style, with the assistance of Chanin's own architect Jacques Delamarre. It incorporates architectural sculpture by Rene Paul Chambellan, as well as a facade of brick and terracotta. The skyscraper reaches 680 feet (210 m), with a 649-foot-tall (198 m) roof topped by a 31-foot (9.4 m) spire. The Chanin Building includes numerous setbacks to conform with the 1916 Zoning Resolution.

The Chanin Building was constructed in 1927–1929, and was almost fully rented upon opening. Over the years, the upper floors have contained a movie theater, observation deck, and radio broadcast station, while the lower floors were used as offices and a bus terminal. The building was designated a New York City landmark in 1978, and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

Description

The Chanin Building was designed by Sloan & Robertson in the Art Deco style. Though the exterior contains a relatively muted design, the interior contains ample ornament.[2] The building's design took several elements from Eliel Saarinen's Tribune Tower design.[3][4] The Chanin Building is 649 feet (198 m) tall to its roof, or 680 feet (210 m) tall when including its spire.[5]

The building is located at 122 East 42nd Street and is bounded by Lexington Avenue to the east, 42nd Street to the north, and 41st Street to the south.[6][7] The lot measures 125 feet (38 m) along 42nd Street, 175 feet (53 m) along 41st Street, and 197.5 feet (60.2 m) along Lexington Avenue.[8] It is part of the Terminal City area of Grand Central Terminal, and abuts 110 East 42nd Street directly to its west.[9] The Grand Hyatt New York hotel is located across 42nd Street,[9][10] while the Socony–Mobil Building is located across Lexington Avenue.[9]

Form

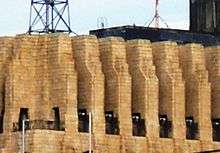

The Chanin Building employs a series of setbacks[2][4] that end in a "vigorous, toothed" pinnacle.[2] Because of the varying widths of the surrounding streets, three separate groups of setbacks were mandated for each side per the 1916 Zoning Resolution,[4][11][12] with the result that the Chanin Building was "design[ed] in masses rather than in facades".[13] The lowest four stories occupy the entire building lot, while there is a recession in the middle of the eastern facade from the fifth through 17th stories. The subsequent stories form a jagged "pyramid", with setbacks above the 17th, 30th, and 52nd stories.[14]

Facade

The Chanin Building is clad with brick, limestone, and terracotta,[8] as well as bronze, marble, and colored glass ornament that was custom-designed.[15] The base of the building bears black Belgian marble around the store front windows, which are each made of plate glass. Directly above, a bronze frieze depicts scenes of evolution, ranging from simple organisms to more complex animals and plants.[14][16] A second terracotta frieze runs the whole length of the lower facade, presenting a dramatic collection of angular zigzags and curvy leaves.[14] A bas-relief by Edward Trumbull, designed in the Art Deco style, wraps around the facade.[2][7]

The facade continues upward in relatively simple tones.[2] The second and third floors include bronze-framed groups of triple-paned windows, with bronze Art Deco spandrel panels between the floors. Each grouping is separated by vertical piers made of limestone, topped by elaborate capitals. The fourth story is faced with ornate terracotta panels depicting plants, evoking the stylized forms common in the Art Deco style.[14] There are buttresses on the fifth and sixth stories of the Lexington Avenue facade's recessed section, and at the corners of the 30th through 49th stories.[17] The crown, above the Chanin Company's 52nd floor offices, contains abstract-patterned projecting ornamentation.[18]

Originally, 212 artificial candles at the top of the Chanin Building provided the equivalent of 30 million candlepower.[19] These lights, meant to highlight the details of the building, were characteristic of the Art Deco style,[18] and on cloudless nights, could be seen from more than 40 miles (64 km) away.[2] They had been toned down by the late twentieth century.[18]

Features

The interior design was mostly the work of Rene Paul Chambellan and Jacques Delamarre. The former specialized in architectural sculpture in numerous styles, such as the Art Deco style, while the latter worked for the Chanin Company.[20]

Lobby

The lobby is accessed by passageways from 42nd and 41st Streets, with a side entrance from Lexington Avenue.[21] The lobby is decorated in a "modernistic" style themed around "The City of Opportunity".[22][23] Eight bronze reliefs designed by Chambellan perch above ornate bronze radiator grilles. The grilles depict four categories of physical and mental life.[24] The bronze ornamentation continues in the waves on the floor, mailboxes, and elevator doors extending the general Art Deco style from the outside inward.[22] The lobby also contains other ornamentation such as terrazzo floors with bronze inlays, as well as tan marble walls.[21]

Marble stairs lead to the basement where there are connections to Grand Central Terminal and the New York City Subway's Grand Central–42nd Street station.[20][23] Also inside are 21 high speed passenger elevators, split up into three elevator banks,[8][21] as well as one service elevator. When the building was opened, the first floor, mezzanine, and second floor were used by banks and other commercial concerns.[8]

The lobby originally served as a "palatial" bus terminal operated by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.[25] The terminal was outfitted with marble surfaces and also contained waiting rooms and ticket offices.[26] Buses would pull onto a revolving turntable within the terminal, which received boarding passengers on one side and deposited alighting passengers on the other.[22] The coach terminal closed after the railroad discontinued all passenger service north of Baltimore in 1958.[27]

Upper floors

The third through 48th floors consist almost entirely of leasable office space, while the 49th and 50th floors contain the Chanin brothers' board room and offices.[8] When originally completed, the 50th floor also had a small movie theater, which was later converted into the Chanin Organization's offices.[15][17] The floors above the 52nd floor were originally the offices of the Chanin Organization, with an Art Deco restroom that a building trade convention's judges referred to as "America's finest bathroom".[15][22] Irwin Chanin's 52nd floor offices were accessed through a set of bronze gates designed by Chambellan, while bronze vector grilles were situated within the office.[22]

As a dominant landmark in the midtown skyline upon its opening, the building had an open-air observation deck on the 54th floor.[22] It was one of three open-air observatories in the city following World War II, the others being at 30 Rockefeller Plaza and at the Empire State Building, though there had been several other observation decks in the city prior to the war. The Chanin Building only charged 25 cents for admission, since it was not as well known as the other two buildings with outdoor observatories.[28] Over the years, several people have committed suicide by jumping off the 54th floor observation deck.[29][30] In later years, other nearby buildings surpassed the Chanin Building in height (including the Chrysler Building, diagonally across Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street), and so the observation deck was closed in the mid-20th century.[15]

The top of the building was used as a transmission site for WQXR-FM starting on December 15, 1941, when it was relocated from Long Island City in Queens.[31] In 1965, the transmitter was moved to the Empire State Building.[32]

History

Context

The completion of the underground Grand Central Terminal in 1913 resulted in the rapid development of the areas around Grand Central, and a corresponding increase in real-estate prices.[33] Among these were the New York Central Building at 47th Street and Park Avenue, as well as the Grand Central Palace across 42nd Street from the present Chanin Building.[34] By 1920, the area had become what The New York Times called "a great civic centre".[35] One site that had yet to be redeveloped was the Manhattan Storage Warehouse, which was built in 1882[8] and still occupied the site of the Chanin Building.[8][12]

Irwin Chanin was an American architect and real estate developer who designed several Art Deco towers and Broadway theaters.[36] He and his brother Henry I. Chanin designed their first Manhattan buildings in 1924[6] and later built and operated a number of theaters and other structures related to the entertainment industry, including the Roxy Theatre and the Hotel Lincoln.[6][37][38] The Chanins took over an existing 105-year leasehold for the land underneath the warehouse in August 1926, upon which they planned to build a skyscraper.[8][12] The brothers still had a reputation for being involved mostly in the theater industry. According to one author, when the Chanins cleared the site in 1927, many members of the general public could not tell "whether the Chanins were builders or [...] theater-owners who had taken up building as a sideline."[39] The warehouse itself was difficult to clear, since its 5-foot-thick (1.5 m) walls had been designed to protect against "burglary, fire and assault".[40] The process entailed clearing away 7,500 truck loads of brick, 1,000 of scrap metal, and 3,500 of loose earth.[41]

Construction

The official plans for the Chanin Building were filed with the New York City Department of Buildings in June 1927, at which point 60% of the warehouse had been demolished. Sloan & Robertson, architects of the nearby Graybar Building, Pershing Square Building, and 110 East 42nd Street, were hired to design the Chanin Building.[8]

Once the foundation had been laid, the first steel columns were installed in January 1928, with Irwin S. Chanin driving in the first rivet.[12][42] The steel frame weighed an estimated 15,000 short tons (13,000 long tons) and was held together by 1.5 million rivets and 160,000 bolts.[43] Crowds frequently stopped to observe the construction process.[44] The erection of the frame was not without problems: in one incident, the boom of a construction derrick fell from the 20th floor, nearly splitting a truck in half, though no one was injured or killed.[45] The steelwork was completed by that June,[43] and as was tradition at the time, two gold rivets for the Chanin Building were driven into the frame on July 2 to mark this event.[46] The building held its topping out ceremony in August 1928.[23]

Usage

The structure was declared complete on January 23, 1929, exactly one year after the first rivet had been driven into the building.[46] It opened January 29 at an estimated cost of $12-14 million, with an informal opening attended by mayor Jimmy Walker.[23][47] The Chanin Building thus became the first major skyscraper in Terminal City, and the third-tallest building in New York City behind the Woolworth Building and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower.[12] Though the Chanin Building was later surpassed in height by other buildings, including the adjacent 1,046-foot (319 m) Chrysler Building that opened a year later,[48] Irwin Chanin was instead focused on attracting tenants with an "efficient, up-to-date" facility.[12]

Upon opening, the Chanin Building was almost fully rented.[39] The builders projected that by September 1, 1929, the building would be 70% rented, though the actual occupancy rate at that date was 92%. Furthermore, in 1930, The New York Times reported that 95% of the structure's 710,000 square feet (66,000 m2) was occupied by 9,000 workers.[49] Initially, the lobby space was occupied by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's bus terminal, ticket offices, and waiting rooms.[26] The office space included such tenants as the Kimberly-Clark paper company,[50] Pan American Petroleum and Transport Company,[51] and Fairchild Aircraft,[52] while the Chanin company took all the space above the 50th floor.[2] In addition, the Sterling National Bank took up much of the mezzanine space on the Lexington Avenue side,[53] and a self-service and table-service restaurant opened in the basement.[54] Through the Great Depression, leasing proceeded actively.[55]

The building's owners filed to reorganize the operations of the Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street Corporation, which operated the Chanin Building, in 1947.[56] In subsequent years, the Chanin Building continued to attract tenants such as Guest Keen and Nettlefolds,[57] a Howard Johnson's restaurant,[58] and the Barry Goldwater 1964 presidential campaign's New York state headquarters.[59] In addition, the building hosted U.S. Chess Championships.[60] Despite this success, the Chanin Building faced some issues: its owners, along with those of the Nelson Tower and Century Apartments, were charged with real estate tax fraud in 1974.[61] The Chanin Building's owners were estimated to have evaded $138,549 in real estate taxes.[62]

The Chanin Building was designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1978,[63] and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[64] By the 1990s, the building was owned by a syndicate headed by Stanley Stahl.[65][66] Modern tenants include the Apple Bank for Savings,[67] of which Stahl was the only stockholder,[68] as well as the International Rescue Committee, which had moved to the building in 1994.[65][69]

Critical reception

Shortly after the building's completion, architectural critic Matlack Price wrote in an Architectural Forum article that "The architects have not here compromised a fine vision either with major errors in scale or with minor trivialities."[13] Paul Goldberger of The New York Times said that the Chanin Building was "one of the pre-eminent pieces of American Art Deco—a gracefully ornamented, 56-story slab".[70] The fifth edition of the AIA Guide to New York City, published in 2010, characterized the Chanin Building as being "classic style, rather than stylish ephemera. Such distinguished self-improvement seems beyond the grasp of current developers."[37]

The interior design of the building was also praised. Herbert Muschamp wrote in 1992 that the Chanin Building "tells a story of New York as the legendary beacon for immigrants", and that its numerous amenities "were integral to the Chanin Building's drama".[71] Historian Donald L. Miller stated, "Restrained on the outside, the inside is exuberantly ornate".[2]

See also

References

Notes

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Miller 2015, p. 245.

- Robinson, Cervin. (1975). Skyscraper style : art deco, New York. Bletter, Rosemarie Haag. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-19-501873-7. OCLC 1266717.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 7.

- "Chanin Building – The Skyscraper Center". www.skyscrapercenter.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 1; National Park Service 1980, p. 4.

- White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 314.

- "Chanins Will Build $12,000,000 Tower; 52-Story Office Building Will Rise in Lexington Avenue, Between 41st and 42d". The New York Times. June 22, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 315.

- Goldberger, Paul (January 11, 1978). "The Commodore Being Born Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "The Chanin Building, New York City". Architecture and Building. 61: 39. February 1929.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 2; National Park Service 1980, p. 6.

- Architectural Forum 1929, p. 699.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- "Atop the Former Observation Deck of NYC's Chanin Building". Untapped New York. March 30, 2018. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Ermengem, Kristiaan Van. "Chanin Building, New York City". A View On Cities. Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 4; National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 4; National Park Service 1980, p. 3.

- "To Light New Skyscraper; Equivalent of 30,000,000 Candle power for Chanin building". The New York Times. January 14, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 3.

- National Park Service 1980, p. 3.

- Miller 2015, p. 246.

- "Walker at Opening of Chanin Building; Other Officials Visit Tallest Skyscraper in the Midtown Section". The New York Times. January 30, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Architectural Forum 1929, p. 698.

- Gray, Christopher (November 3, 2011). "A Bus Terminal, Overshadowed and Unmourned". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "B. & O. Opens Bus Station; Inaugurates Coach Service in Chanin Building Today". The New York Times. December 17, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Matteo, Thomas (April 23, 2015). "B&O Railroad had strong presence on Staten Island for 100 years". Staten Island Advance. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Lindheim, Burton (August 31, 1947). "Sight-Seeing from New York's Skyscrapers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Nurse Killed in Plunge; Mother of Two Leaps From the Chanin Building Tower". The New York Times. July 6, 1946. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Woman Dies in Plunge; Drops From Observation Tower of the Chanin Building". The New York Times. November 13, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Frequency Modulation Business. 1946. p. 35. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "A Visual History of WQXR : Slideshow". WQXR. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Fitch, James Marston; Waite, Diana S. (1974). Grand Central Terminal and Rockefeller Center: A Historic-critical Estimate of Their Significance. Albany, New York: The Division. p. 6.

- "Pershing Square Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 25, 2016. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- "Another Building For Terminal Zone; 12-Story Commercial Structure to be Erected Opposite the Commodore Hotel". The New York Times. September 14, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 17, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- Dunlap, David W. (February 26, 1988). "Irwin Chanin, Builder of Theaters And Art Deco Towers, Dies at 96". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 316.

- Miller 2015, p. 234.

- Miller 2015, p. 232.

- Miller 2015, p. 235.

- Contractors and Engineers. Buttenheim-Dix Publishing Corporation. 1928. p. 130. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Chanins Set Steel; First Columns Placed for Fiftytwo-Story Building". The New York Times. January 20, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Gold Rivet for Chanin Building". The New York Times. June 29, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Miller 2015, p. 237.

- Miller 2015, p. 240.

- Miller 2015, p. 245; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 2; National Park Service 1980, p. 6.

- "Mayor Walker Opens 56-Story Chanin Building". The Brooklyn Citizen. January 30, 1929. p. 5. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via newspapers.com

- "Chrysler Building, City's Highest, Open". The New York Times. May 28, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- "Chanin Building 95% Rented". The New York Times. January 30, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Paper Company Leases; Kimberly-Clark Co. Takes Floor in New Chanin Building". The New York Times. January 24, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Chanin Building Lease; Pan-American Petroleum Takes 3 Floors--Other Space Deals". The New York Times. August 16, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Leases in Chanin Building; Fairchild Aviation Corp. Takes Forty-eighth Floor". The New York Times. January 26, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Sterling National in Chanin Building". The New York Times. February 5, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Leases in Chanin Building; Exchange Buffet Affiliate to Operate Two Restaurants". The New York Times. June 13, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Tenants Renew Leases; Chanin Building Renting Is Reported Active". The New York Times. December 15, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- "Rabin Named Referee; Will Study Plans for the Chanin Building Reorganization". The New York Times. June 29, 1945. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Space is Leased by Steel Plant; Cardiff Concern Gets Office in Chanin Building". The New York Times. November 6, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Howard Johnson Plans 42d St. Unit; Chanin Building Restaurant to Be Company's Largest". The New York Times. October 2, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Goldwater Is Heard Here; State Headquarters Opened". The New York Times. March 25, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Title Chess Tourney Set; U.S. Championship Play to Open in Chanin Building Oct. 20". The New York Times. July 31, 1946. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Building Corporation Accused Of Fraud for Lower Realty Tax". The New York Times. June 28, 1974. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Fried, Joseph P. (June 6, 1974). "2 Realty Concerns and Lawyer Indicted on Tax‐Fraud Charges". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 1978, p. 1.

- National Park Service 1980, p. 1.

- Scherreik, Susan (February 9, 1994). "Real Estate; The American Express Bank is relocating 300 of its employees to new space at 7 World Trade Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Stoler, Michael (November 23, 2005). "Leaders Cross Over Into the Banking Industry". The New York Sun. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Branch Locations | New York Bank | Banks in New York | Apple Bank". www.applebank.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Berger, Joseph (April 29, 2011). "Landmarks Are Called a Hardship, Setting Off a Fight". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Contact the IRC". International Rescue Committee (IRC). June 17, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Goldberger, Paul (December 7, 1982). "Architecture: Chanin a Master of the Skyline". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Muschamp, Herbert (July 12, 1992). "Architecture View; For All the Star Power, a Mixed Performance". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

Sources

- "Chanin Building" (PDF). Architectural Forum. 50: 693–700. May 1929. (PDF pp. 101–108)

- Adams, Rayne (May 1929). "The Reliefs and Grilles of the Chanin Building Vestibules" (PDF). Architectural Forum. 50: 693–698. (PDF 101–106)

- Price, Matlack (May 1929). "The Chanin Building" (PDF). Architectural Forum. 50: 699–700. (PDF 107–108)

- "Chanin Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 14, 1978.

- "Historic Structures Report: Chanin Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 23, 1980.

- Miller, D.L. (2015). Supreme City: How Jazz Age Manhattan Gave Birth to Modern America. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-5020-4.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.