Cannabis in India

Cannabis in India has been used since as early as 2000 BCE. In Indian society, common terms for cannabis preparations include charas (resin), ganja (flower), and bhang (seeds and leaves), with Indian drinks, such as bhang lassi and bhang thandai made from bhang being one of the most common legal uses.

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Regional

|

|

Variants |

|

As of 2000, per the UNODC the "prevalence of usage" of cannabis in India was 3.2%.[1] A 2019 study conducted by the All India Institutes of Medical Sciences reported that about 7.2 million Indians had consumed cannabis within the past year.[2] The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment's "Magnitude of Substance Use in India 2019" survey found that 2.83% of Indians aged 10–75 years (or 31 million people) were current users of cannabis products. According to the UNODC’s World Drug report 2016, the retail price of cannabis in India was US$0.10 per gram, the lowest of any country in the world.[3]

History

Antiquity

.jpg)

Bhanga is mentioned in several Indian texts dated before 1000 CE. However, there is philological debate among Sanskrit scholars as to whether this bhanga can be identified with modern bhang or cannabis.[5]

Cannabis sativa is one of the candidates for the identity of the plant that was used to prepare soma in Vedic period.[6] Soma was an intoxicating ritual drink that has been highly praised in the Rigveda (c. 1700–1100 BCE).

Atharvaveda (c. 1500–1000 BCE) mentions bhanga as one of the five sacred plants that relieve anxiety. Sayana interpreted bhanga as a type of wild grass, but many scholars identify bhanga with cannabis.[7] The relevant verse:

To the five kingdoms of the plants which Soma rules as Lord we speak.

darbha, hemp, barley, mighty power: may these deliver us from woe,

The five kingdoms of plants, having Soma as their chief, we address;

the darbha, hemp, barley, saha — let them free us from distress.

Sushruta Samhita (c. 600 BCE) again mentions bhanga, as a medicinal plant, and recommends it for treating catarrh, phlegm and diarrhea.[5]

According to Gerrit Jan Meulenbeld and Dominik Wujastyk, Chikitsa-sara-sangraha (c. late 11th century) by Vangasena is the earliest extant Indian text that features an uncontested mention of cannabis. It mentions bhanga as an appetiser and a digestive, and suggests it in two recipes for a long and happy life. Narayan Sarma's Dhanvantariya Nighantu, a contemporary text, mentions a narcotic of the plant.[5] Nagarjuna's Yogaratnamala (c. 12th–13th century) suggests that cannabis (mdtuldni) smoke can be used to make one's enemies feel possessed by spirits. Sharngadhara Samhita (13th century) also gives medicinal uses of cannabis, and along with ahiphena (opium poppy), mentions it as one of the drugs which act very quickly in the body.[5]

Cannabis also finds its mention in other historic scriptures like Dhanvantari Nighantu, Sarngandhara Samhita and Kayyadeva Nighantu. It is also referred in Ayurveda as an ingredient in various recipes of pain relievers and aphrodisiacs, but in small quantities. It is noted that large quantity or long time consumption can be addictive and that it is more dangerous than tobacco for lungs and liver.[10] Ayurveda however does not use cannabis for smoking recipes.[11]

The Hindu god Shiva is said to have chosen cannabis as his favorite food, after having spent one night sleeping under the plant's leaves and when eating of it in the morning refreshed him. Another legend suggests that when the poison Halahala came out from the Samudra manthan, Shiva drank it to protect everyone from it. Later, bhang was used to cool him down. Shiva Purana suggests offering bhang to Shiva during the summer months. But not all devotees offer bhang to Shiva.[12]

Many Ayurvedic texts mention cannabis as vijaya, while tantric texts mention it as samvid.[7]

Colonial India

Portuguese India

Following the Portuguese seizure of Goa in 1510, the Portuguese became familiar with the cannabis customs and trade in India. Garcia de Orta, a botanist and doctor, wrote about the uses of cannabis in his 1534 work Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs and Medicinal Matters of India and of a Few Fruits. Garcia noted that bhang was used to improve work and appetite and enable labour, and "I believe that it is so generally used and by such a number of people that there is no mystery about it.”[13] Fifteen years later Cristobal Acosta produced the work A Tract about the Drugs and Medicines of the East Indies, outlining recipes for bhang.[14]

British India

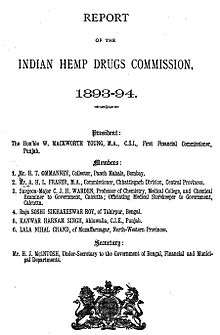

The British Parliament enacted a tax on bhang, ganja and charas in 1798, stating that the tax was intended to reduce cannabis consumption "for the sake of the natives' good health and sanity".[15] In 1894, the British Indian government completed a wide-ranging study of cannabis in India. The report's findings stated:

Viewing the subject generally, it may be added that the moderate use of these drugs is the rule, and that the excessive use is comparatively exceptional. The moderate use practically produces no ill effects. In all but the most exceptional cases, the injury from habitual moderate use is not appreciable. The excessive use may certainly be accepted as very injurious, though it must be admitted that in many excessive consumers the injury is not clearly marked. The injury done by the excessive use is, however, confined almost exclusively to the consumer himself; the effect on society is rarely appreciable. It has been the most striking feature in this inquiry to find how little the effects of hemp drugs have obtruded themselves on observation.

— Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1894-1895[16]

Modern use

As bhang, cannabis is still popular in India.[18] It is also mixed in thandai, a milkshake-like preparation. Bhang is consumed as prasad of Shiva, and is popular between Mahashivaratri and Holi (February–March).[19] Among Sikh Nihangs, bhang is popular, especially during Hola Mohalla.[20][21] Muslim Indian Sufis place the spirit of Khidr within the cannabis plant, and consume bhang.[22][23]

Even in Assam, where bhang has been explicitly banned since 1958, it is consumed by thousands during the Ambubachi Mela. In 2015, the police did not stop devotees from consuming bhang, although they fined two people for smoking tobacco in public places, under the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Act.[24]

In November 2015, Uttarakhand legalized the cultivation of cannabis for industrial purposes.[25] Patanjali Ayurved CEO Balkrishna stated in February 2018 that his company had begun researching the benefits of cannabis and its extracts at its research and development facility in Haridwar, for use in the company's medicines and other products.[26] Madhya Pradesh's Law Minister, P.C. Sharma stated on 20 November 2019 that the state was considering legalising the cultivation of cannabis for medical and industrial purposes.[27] Manipur Chief Minister N. Biren Singh informed the State Assembly on 21 February 2020 that his government was considering legalising the cultivation of cannabis for medical and industrial purposes.[28]

Indian law enforcement agencies seized a total of 182,622 kg of ganja and 2,489 kg of hashish in 2016.[29] Enforcement agencies eradicated 1,980 hectares of illicit cannabis cultivation in 2018, lower than the 3,446 hectares eradicated in 2017. The International Narcotics Control Board's 2019 annual report noted that "India is among those countries worldwide with the greatest extent of illicit cannabis cultivation and production.[30]

The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment's "Magnitude of Substance Use in India 2019" survey found that 2.83% of Indians aged 10-75 years (or 31 million people) were current users of cannabis products, with 0.66% of the population considered to be using cannabis "in a dependent pattern". The survey found that 2.02% of the population consumed bhang and 1.21% consumed charas or ganja. It also noted that most cannabis users were male with 5% of the male population consuming cannabis compared to 0.6% of the female population. The survey found that cannabis use was most prevalent in Sikkim, where 7.3% of the population reported using cannabis, followed by Nagaland (4.7%), Odisha (4.7%) Arunachal Pradesh (4.2%) and Delhi (3.8%). The lowest cannabis use was reported in Puducherry, Kerala, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Lakshadweep, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Gujarat and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, all of which recorded about 0.1% of the population as having used cannabis.[31]

A study by the German data firm ABCD found that New Delhi and Mumbai were the third and sixth largest cannabis consuming cities in the world in 2018, consuming 38.2 tonnes and 32.4 tonnes of cannabis respectively.[32]

Naxalites are heavily invested in illegal production of Ganja.[33]

Legal status

Attempts at criminalising cannabis in British India were made, and mooted, in 1838, 1871, and 1877.[34]

The 1961 international treaty Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs classed cannabis with hard drugs. During the negotiations, the Indian delegation opposed its intolerance to the social and religious customs of India. As a compromise, the Indian Government promised to limit the export of Indian hemp, and the final draft of the treaty defined cannabis as:[35]

"Cannabis" means the flowering or fruiting tops of the cannabis plant (excluding the seeds and leaves when not accompanied by the tops) from which the resin has not been extracted, by whatever name they may be designated.

— Commentary on the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961: Paragraph I, subparagrah (b).Commentary on the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961

Bhang was thus left out from the definition of "cannabis". This allowed India to carry on the tradition of large-scale consumption of bhang during Holi. The treaty also gave India 25 years to clamp down on recreational drugs. Towards the end of this exemption period, the Indian government passed the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act in 1985.[36]

The NDPS maintained the same definition of "cannabis", excluding bhang from its purview:

"cannabis (hemp)" means:

- charas, that is, the separated resin, in whatever form, whether crude or purified, obtained from the cannabis plant and also includes concentrated preparation and resin known as hashish oil or liquid hashish;

- ganja, that is, the flowering or fruiting tops of the cannabis plant (excluding the seeds and leaves when not accompanied by the tops), by whatever name they may be known or designated; and

- any mixture, with or without any neutral material, of any of the above forms of cannabis or any drink prepared therefrom;

— Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (India), Chapter I, Section 2.iii.

NDPS banned the production and sale of cannabis resin and flowers, but permitted the use of the leaves and seeds, allowing the states to regulate the latter.[37]

Cultivation of cannabis for industrial purposes such as making industrial hemp or for horticultural use is legal in India. The National Policy on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances recognizes cannabis as a source of biomass, fibre, and high-value oil. The Government of India encourages research and cultivation of cannabis with low THC content.[26]

Regional bans on bhang

Although NDPS allows consumption of bhang, various states have their own laws banning or restricting its use. In some states, only authorised dealers are allowed to sell bhang. Some states also have rules about the maximum amount of bhang one person can carry and the minimum age of the buyer.[38]

In Assam, The Assam Ganja and Bhang Prohibition Act, 1958, prohibits sale, purchase, possession and consumption of ganja and bhang.[39][24]

In Maharashtra, Section 66(1)(b) of the Bombay Prohibition (BP) Act, 1949, bans manufacture, possession and consumption of bhang and bhang-containing substances without a license.[40]

On 21 February 2017, Gujarat legalized bhang by removing it from the list of "intoxicating drugs" covered by section 23 of the Gujarat Prohibition Act. Gujarat's Minister of State for Home and Prohibition, Pradipsinh Jadeja, explained, "Bhang is consumed only as prasad of Lord Shiva. The state government has received complaints of misuse of prohibition act against those found drinking bhang. Hence, keeping in view the sentiments of public at large, the government has decided to exempt bhang from the ambit of Gujarat Prohibition Amendment Act. Bhang is less intoxicating as compared to ganja."[41]

Reform

In 2015, the first organised efforts to re-legalise cannabis in India appeared, with the holding of medical marijuana conferences in Bangalore, Pune, Mumbai and Delhi by the Great Legalisation Movement India.[42] Many articles and programs in the popular media have also begun to appear pushing for a change in cannabis laws.[43]

In March 2015, Lok Sabha MP for Dhenkanal Tathagata Satpathy stated on a Reddit AMA that he supported the legalisation of cannabis, and also admitted to having consumed the drug on several occasions when he was in college. He later repeated his comments on television and during interactions with the media.[44][45][46] On 2 November 2016, Lok Sabha MP Dharamvir Gandhi announced that he had received clearance from Parliament to table a Private Member's Bill seeking to amend the NDPS Act to allow for the legalised, regulated, and medically supervised supply of "non-synthetic" intoxicants including cannabis and opium.[47]

In July 2017, Union Minister of Women and Child Development Maneka Gandhi suggested the legalization of medical marijuana on the grounds that it would reduce drug abuse and aid cancer patients at the second meeting of the group of ministers to examine the draft Cabinet note for the National Drug Demand Reduction Policy.[48] About a week after the minister's statement, the Union Government issued the first-ever licence to grow cannabis for research purposes to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), in collaboration with the Bombay Hemp Company (BOHECO).[49]

On 12 December 2017, Viki Vaurora, the founder of the Great Legalisation Movement India, penned an open letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and all members of Parliament advocating the urgent need to legalise the cultivation of cannabis and hemp for medical and industrial use.[50][51] In February 2018, the Prime Minister's Office sent a notification to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare directing the ministry to examine the potential benefits associated with cannabis and issue a response to the letter.[52]

On 5 June 2018, Lok Sabha MP from Thiruvananthapuram Shashi Tharoor wrote an opinion piece expressing support for the legalization of cannabis, and concluding that it was "high time for India to embrace the health, business, and broader societal benefits that legally regulating cannabis can bring".[53]

In July 2019, the Delhi High Court agreed to hear a petition, filed by the Great Legalisation Movement Trust, challenging the ban on cannabis. The public interest litigation argues that grouping cannabis with other chemical drugs under the NDPS Act is "arbitrary, unscientific and unreasonable".[54]

Medical research

The Central Council For Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS), a research body under the Ministry of AYUSH, announced the results of the first clinical study in India on the use of cannabis as a restorative drug for cancer patients on 25 November 2018. The pilot study was conducted in collaboration with the Gujarat Ayurved University, Jamnagar on cancer patients undergoing treatment at the Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai. CCRAS Director General Vaidya K.S. Dhiman stated, "In the pilot study conducted earlier this year, cannabis leaves-based drugs have been found effective in alleviating pain and other symptoms in cancer patients post- chemo and radiotherapy."[55]

Bombay Hemp Company (BOHECO) co-founded by Mr Jahan Peston Jamas collaborated with CSIR and hosted a conference to promote the use of cannabis-based medicines in Delhi on 23 November 2018. The conference, called "Cannabis R&D in India: A Scientific, Medical and Legal Perspective", was attended by Minister of State for PMO Jitendra Singh and MP Dharamvir Gandhi.[56][57] On the same day, the Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine (IIIM) of the CSIR announced that it was developing three cannabis-based medicines to treat cancer, epilepsy, and sickle-cell anaemia.[58][59]

The first medical cannabis clinic in India was opened in Koramangala, Bangalore on 1 February 2020.[60][61] The clinic, operated by Odisha-based HempCann Solutions, sells cannabis infused tablets and oils under the brand name Vedi Herbals.[62]

In popular culture

In film

Cannabis has often been depicted in Indian cinema. Historically, Hindi films have portrayed cannabis use negatively depicting the drug as being associated with an upper class hippie culture or as an addictive substance used by criminals. On the other hand, consumption of bhang was often celebrated in popular film songs such as Jai Jai Shiv Shankar and Khaike Paan Banaraswala and the famous track Manali trance . The negative portrayals of cannabis began to undergo a change from the 2000s. Films such as Shaitan (2011), Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana (2012), Kapoor & Sons and The Blueberry Hunt (2016) feature urban middle-class protagonists using cannabis as form of relaxation. Go Goa Gone (2013) was described as the first Hindi-language stoner comedy. Bejoy Nambiar, who wrote and directed Shaitan, believes that "there's a culture of smoking up among today's youth and it's becoming more and more relevant in our movies."[63]

References

- Report of the International Narcotics Control Board (2008). DIANE Publishing. May 2009. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-4379-1361-3.

- "After alcohol, India has a rising cannabis addiction problem, warns AIIMS study". Business Insider. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Infographic: Cannabis-and-opium-based drugs cheapest in India - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Staelens, Stefanie. "The Bhang Lassi Is How Hindus Drink Themselves High for Shiva". Vice.com. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- Ethan Russo (2006). Raphael Mechoulam (ed.). Cannabis in India: ancient lore and modern medicine (PDF). Cannabinoids as Therapeutics. Springer. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9783764373580. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2015-07-17.

- Chris Bennett (2010). "Cannabis and the Soma Solution". Trine Day. ISBN 9781936296323.

- Chris Conard (1997). Hemp for Health. Inner Traditions. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780892815395.

- Hymns of the Atharva Veda, by Ralph T.H. Griffith, 1895

- William Dwight Whitney (1905). Atharva-Veda Saṃhitā, Volume 2. p. 438. ISBN 9788171101740.

- Frawley, David (2012). Soma in Yoga and Ayurveda: The Power of Rejuvenation and Immortality. Lotus Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0940676213. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Gilman, Sander L. (2004). Smoke: A Global History of Smoking. Reaktion Books. p. 74. ISBN 1861892004. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Tod Mikuriya (1994). Excerpts from the Indian Hemp Commission Report. Last Gasp. p. 38. ISBN 0867194200. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- John Charles Chasteen (9 February 2016). Getting High: Marijuana through the Ages. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-1-4422-5470-1.

- Martin Booth (16 June 2015). Cannabis: A History. St. Martin's Press. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-1-250-08219-0.

- Dixit, Prajwal. "How cannabis was criminalized". The Telegram. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "(298) Page 264 - India Papers > Medicine - Drugs > Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1894-1895 > Volume I - Medical History of British India - National Library of Scotland". nls.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Ayyagari S (2007). ""Hori Hai": A Festival of Colours!! (review)". Asian Music. Johns Hopkins University Press. 38 (2): 151–153. doi:10.1353/amu.2007.0029.

- Leslie L. Iversen (6 November 2007). The Science of Marijuana. Oxford University Press. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-0-19-979598-7.

- "Bhang, thandai market booms". The Times of India. 2014-02-27.

- Hola Mohalla: United colours of celebrations,

- "Mad About Words". Telegraphindia.com. 2004-01-03. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- Lloyd Ridgeon (2006). Sufi Castigator: Ahmad Kasravi and the Iranian Mystical Tradition. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 9781134373987.

- Michael Knight (2009). Journey to the End of Islam. Soft Skull. p. 28. ISBN 9781593765521.

- Samudra Gupta Kashyap (2015-06-23). "Kamakhya ushers in annual festival, with annual cannabis problem".

- "Uttarakhand To Become First Indian State To Legalise Cannabis Cultivation". Indiatimes. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Tandon, Suneera. "India's cannabis economy has a new hope—Patanjali". Quartz. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Madhya Pradesh govt to legalise cannabis cultivation". Deccan Herald. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Manipur government considering legalising cannabis plantation". Hindustan Times. 22 February 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Balachandran, Manu. "The push to make marijuana legal in India now has support from one of Narendra Modi's ministers". Quartz. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "INCB raises concern over illicit cultivation of cannabis in India, its impact on children | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Magnitude of Substance Use in India 2019" (PDF). Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. pp. 17–19. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Sharma, Niharika. "Delhi consumes more weed than Los Angeles, Mumbai more than London". Quartz India. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Aug 7, Siva G. / TNN /; 2020; Ist, 11:33. "Maoists into cultivation of ganja now, say Vizag cops | Visakhapatnam News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2020-08-08.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- A Cannabis Reader: Global Issues and Local Experiences : Perspectives on Cannabis Controversies, Treatment and Regulation in Europe. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. 2008. p. 100. ISBN 978-92-9168-311-6.

- Gabriel G. Nahas and Henry Clay Frick (2013). Drug Abuse in the Modern World: A Perspective for the Eighties. Elsevier. p. 262. ISBN 9781483140940.

- Manoj Mitta (2012-11-10). "Recreational use of marijuana: Of highs and laws". The Times of India.

- Jonathan P. Caulkins; Angela Hawken; Beau Kilmer; Mark Kleiman (14 June 2012). Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to KnowRG. Oxford University Press. pp. 139–. ISBN 978-0-19-991372-5.

- Aditi Malhotra (2015-03-06). "Is it Legal to Get High on Bhang in India?".

- "Assam Gania and Bhang Prohibition Act, 1958" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-28. Retrieved 2015-07-17.

- Vaibhav Ganjapure (2012-06-28). "'Bhang'is intoxicant, its possession is prohibited: HC". The Times of India.

- "Gujarat further tightens prohibition". The Times of India. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "City to host country's first 'legalise marijuana' meet". Bangaloremirror. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Why India Should Legalise Marijuana". Man's World India. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- "Make cannabis consumption legal; ban is turning people alcoholic: BJD chief whip Tathagata Satpathy". The Indian Express. 11 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Cannabis ban is elitist. It should go: Tathagata Satpathy". The Times of India. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "BJD MP Tathagata Satpathy Tells How to Score Weed". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Bill for legalised supply of opium, marijuana cleared for Parliament". Hindustan Times. 19 October 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Make marijuana legal for medical needs: Maneka Gandhi". The Times of India. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- Kanti, Anurit. "Bombay Hemp Company To Develop Cannabis Based Medicine". BW Businessworld. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Vaurora, Viki (16 December 2017). "Open letter to the Hon'ble Prime Minister of India, Shri Narendra Modi". Facebook. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- "Projects". Great Legalisation Movement. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- "Check benefits of cannabis, Prime Minister's office tells health ministry". Hindustan Times. 17 February 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- Shashi Tharoor; Avinash Tharoor (5 June 2018). "High time India, the land of bhang, legalises marijuana: Shashi Tharoor". The Print. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Jul 20, Abhinav Garg. "Delhi HC to examine plea to legalise cannabis use". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- "Study finds cannabis-based drugs help alleviate side-effects post-chemo AIIMS to research further". The Week. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Is India Moving Towards Legalising Medical Marijuana?". FIT. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "India Moves in the Direction of Legalizing Medicinal Cannabis". sputniknews.com. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Singh, Kuwar. "Modi's love for ayurveda may be just the push marijuana needed in India". Quartz India.

- "CSIR-IIIM, BOHECO to develop cannabis based drugs for cancer, epilepsy, sickle cell anemia". Business Standard India. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Kumari, Barkha. "India's first cannabis clinic in Koramangala has benefited several Bengalureans". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Kumari, Barkha KumariBarkha. "India's first 'cannabis clinic'". Mumbai Mirror. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Joshi, Shamani (31 January 2020). "India's First Medical Cannabis Clinic Is Finally Here". Vice. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- Ghosh, Sankhayan (17 April 2016). "Smoking the peace pipe". The Hindu. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

Further reading

Primary Sources

- Indian Hemp Drugs Commission (1894–95). Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission, 1893-94. Simla and Calcutta.

- Prain, David (1893). Report on the Cultivation and Use of Ganja. Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press.

- Tull-Walsh, J.H. (September–December 1894). "On Insanity Produced by the Abuse of Ganja and Other Preparations of Indian Hemp, with Notes of Case Studies". IndianMedical Gazette. 29 (9): 333–34, 369–72, 447–51. PMC 5197335. PMID 29001600.

Secondary Sources

- Mills, James H. (2003). Cannabis Britannica: Empire, Trade, and Prohibition, 1800-1928. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199249381.

- Mills, James H. (2000). Madness, Cannabis and Colonialism: The 'Native Only' Lunatic Asylums of British India, 1857-1900. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312233594.

- Ronen, Shamir; Hacker, Daphna (Spring 2001). "Colonialism's Civilizing Mission: The Case of the Indian Hemp Drug Commission". Law & Social Inquiry. 26 (2): 435–461. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2001.tb00184.x. JSTOR 829081.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cannabis in India. |