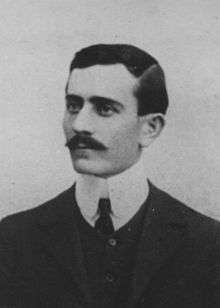

Bogdan Žerajić

Bogdan Žerajić (Serbian Cyrillic: Богдан Жерајић; 1 February 1886 – 15 June 1910) was a Bosnian Serb student of the Faculty of Law at the University of Zagreb.

Bogdan Žerajić | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 February 1886 |

| Died | 15 June 1910 (aged 24) Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary |

| Resting place | Vidovdan Heroes Chapel, Sarajevo[1] |

| Occupation | Student |

| Known for | Being a source of inspiration to Gavrilo Princip |

In 1910 he attempted to assassinate General Marijan Varešanin, the Governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, on the opening day of the Austro-Hungarian Parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina, believing it to be illegal and illegitimate. His attempt was his own initiative, an act of personal revolt against Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[2]

Žerajić was first among the young people of Bosnia and Herzegovina to pursue tyrannicide as a method of political struggle. His act had great impact on young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina, while official press in Sarajevo and Belgrade generally referred to it as an act of a disturbed lunatic, which was also generally the view of an older generation of Sarajevo Serbs.

Secret societies and tyrannicide

Žerajić and Špiro Soldo were leaders of the secret society "Freedom" (Serbian: Слобода) established in 1905/1906.[3] Žerajić's friendship with Vladimir Gaćinović and his attempted assassination of Varešanin additionally inspired the members of the revolutionary movement Young Bosnia, including Gavrilo Princip.[4] Gaćinović was the real ideologue of the revolutionary movement Young Bosnia and advocated tyrannicide as a method of political struggle.[5] Some authors, including Vladimir Dedijer, emphasize that the basis for this method of political struggle is the cult of "Kosovo tyrannicide".[6]

Žerajić was first to apply this method in the practice. When Franz Joseph I of Austria visited Bosnia and Herzegovina on 3 June 1910, Žerajić had intention to attempt his assassination during his visit to Mostar, but eventually gave it up from unknown reason.[7]

Attempted assassination of Varešanin

Žerajić decided to assassinate General Marijan Varešanin, the Governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, after he read an article written by Risto Radulović, who argued against dispiritedness in the public life of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[8] In his article, Radulović explained that he did not see glorious moments of the nation nor a single tragedy which he believed was necessary to temper the struggle. When Žerajić read these words he yelled "There will be a tragedy!".[9]

On 15 June 1910, Žerajić attempted to assassinate Varešanin on the day of opening of the Austro-Hungarian Diet of Bosnia because he believed it was illegal and illegitimate.[10] He shot at Varešanin five times, and missed. With his last, sixth, bullet Žerajić killed himself. Before he died, he said that he expected that Serbdom would avenge his death.[11] His action brought Young Bosnia to the public attention.[12][13]

Reactions

Žerajić's attempt of assassination had a significant influence on young people of Bosnia and Herzegovina. After this attempt new revolutionary circles were established in Sarajevo, Mostar, Tuzla and Banja Luka.[14]

An evening before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Gavrilo Princip, Čabrinović and Ilić visited the grave of Žerajić for the last time.[15] Žerajić's proclamation "He who wants to live, let him die. He who wants to die, let him live", was quoted by Gavrilo Princip in one of the songs he wrote (Serbian: Ал право је рекао пре Жерајић, соко сиви: Ко хоће да живи, нек мре, Ко хоће да мре, нек живи).[16]

The official press in Bosnia and Herzegovina and most of the newspapers from Serbia described Žerajićs attempt as action of disturbed maniac. The older generation of Serbs in Sarajevo had similar position.[17][18]

References

- Pokop.ba. "Sveti Arhangeli Georgije i Gavrilo" (in Bosnian). Retrieved 2019-07-12.

- Ćorović, Ljubinković & Arsić 1997.

- Ljubibratić, Dragoslav (1961). Vladimir Gaćinović. Nolit. p. 35.

- Istorisko društvo Bosne i Hercegovine (1954). Godišnjak. p. 87.

- Лесковац, Младен; Форишковић, Александар; Попов, Чедомир (2004). Српски биографски речник. Будућност. p. 634.

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1966). "КОСОВСКО ТИРАНОУБИСТВО". Sarajevo hiljadu devetstso četraneste. Prosveta.

- Мастиловић, Драга (2009). Херцеговина у Краљевини Срба, Хрвата и Словенаца: 1918-1929. Филип Вишњић. p. 35. ISBN 978-86-7363-604-7.

- Radulovic, Risto (1988). Izabrani radovi. p. 33.

- Glasnik Srpskog istorijsko-kulturnog društva "Njegoš". Njegoš. 1983. p. .

- Srpski književni glasnik. 1935. p. 451.

- Ćorović, Vladimir (1992). Odnosi između Srbije i Austro-Ugarske u XX veku. Biblioteka grada Beograda. p. 624.

- Solarić, Gojko M. (1958). Istorija, 1830-1918 za viii razred osmogodišne škole. Nolit. p. 108.

- John Hance (2014). Chaos, Confusion, and Political Ignorance. p. 386. ISBN 9781490728780.

- Ćorović, Ljubinković & Arsić 1997

Tačno kaže dr. Branko Čubrilović, sam aktivni omladinac, iz jedne borbene nacionalne porodice, da je na bosansku omladinu najviše delovao primer atentata Bogdana Žerajića, izvedenog iz sopstvene iniciative, kao delo dubokog ličnog revolta i kao najrečitiji protest protiv aneksije. Žerajić je bio intimni drug Gaćinovićev i njegov primer delovao je silno na ovog drugog i skrenuo ga konačno na put aktivnosti jednog nacionalnog revolucionara. "Na sve strane, posle Žerajićeva atentata, niču kolone buntovnih kružoka. Sarajevo, Mostar, Tuzla, Banja Luka, daju ton, obeležje u toj borbi.

- Stand To!: The Journal of the Western Front Association. The Association. 2003. p. 44.

On the evening before 28 June 1914 Princip, Cabrinovic and Ilić paid a last visit to the grave of Bogdan Zerajic in Sarajevo. Zerajic had planned an assault ...

- Marković, Marko (1961). Članci i ogledi. p. 193.

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1966). The Road to Sarajevo. Simon and Schuster. p. 249.

Zerajic's attempt was described in the official press in Bosnia as ...

- Bryan Lightbody (2017). Murder of Innocence. p. 306. ISBN 9781524668372.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bogdan Žerajić. |

- Ćorović, Vladimir; Ljubinković, Nenad; Arsić, Irena (1997). Istorija srpskog naroda. Glas srpski.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)