Body proportions

While there is significant variation in anatomical proportions between people, there are many references to body proportions that are intended to be canonical, either in art, measurement, or medicine.

In measurement, body proportions are often used to relate two or more measurements based on the body. A cubit, for instance, is supposed to be six palms. A span is taken to be 9 inches and was previously considered as half a cubit. While convenient, these ratios may not reflect the physiognomic variation of the individuals using them.

Similarly, in art, body proportions are the study of relation of human or animal body parts to each other and to the whole. These ratios are used in depictions of the figure (to varying degrees naturalistic, idealized or stylized), and may become part of an aesthetic canon within a culture.

Basics of human proportions

It is important in figure drawing to draw the human figure in proportion. Though there are subtle differences between individuals, human proportions fit within a fairly standard range, though artists have historically tried to create idealised standards, which have varied considerably over different periods and regions. In modern figure drawing, the basic unit of measurement is the 'head', which is the distance from the top of the head to the chin. This unit of measurement is reasonably standard, and has long been used by artists to establish the proportions of the human figure. Ancient Egyptian art used a canon of proportion based on the "fist", measured across the knuckles, with 18 fists from the ground to the hairline on the forehead. This was already established by the Narmer Palette from about the 31st century BC, and remained in use until at least the conquest by Alexander the Great some 3,000 years later.[1]

The proportions used in figure drawing are:

- An average person is generally 7-and-a-half heads tall (including the head).

- An ideal figure, used when aiming for an impression of nobility or grace, is drawn at 8 heads tall.

- A heroic figure, used in the heroic for the depiction of gods and superheroes, is eight-and-a-half heads tall. Most of the additional length comes from a bigger chest and longer legs.

Western ideal

Leg-to-body ratio

A study using Polish participants by Sorokowski found 5% longer legs than an individual used as a reference was considered most attractive.[4] The study concluded this preference might stem from the influence of leggy runway models.[5] The Sorokowski study was criticized for using a picture of the same person with digitally altered leg lengths which Marco Bertamini felt were unrealistic.[6]

Another study using British and American participants, found mid-ranging leg-to-body ratios to be most ideal.[7]

A study by Swami et al. of American men and women showed a preference for men with legs as long as the rest of their body and women with 40% longer legs than the rest of their body. The researcher concluded that this preference might be influenced by American culture where long-legged women are portrayed as more attractive.[8] The Swami et al. study was criticized for using a picture of the same person with digitally altered leg lengths which Marco Bertamini felt were unrealistic. Bertamini also criticized the Swami study for only changing the leg length while keeping the arm length constant. Bertamini's own study which used stick figures mirrored Swami's study, however, by finding a preference for leggier women.[6]

Another common measurement of related to leg-to-body ratio is sitting-height ratio (SHR). Sitting height ratio is the ratio of the head plus spine length to total height which is highly correlated to leg-to-body ratio. SHR has been found to be very different between individuals of different ancestry. It has been reported that individuals with African ancestry have on average longer leg length, i.e. lower SHR than individuals of European ancestry.[9] A study in 2015 revealed that this difference is mainly due to genetic differences and the SHR difference between African and European individuals is as large as 1 standard deviation.[10]

Muscular men and thin women

A 1999 study found that "the (action) figures have grown much more muscular over time, with many contemporary figures far exceeding the muscularity of even the largest human bodybuilders," reflecting an American cultural ideal of a super muscular man. Also, female dolls reflect the cultural ideal of thinness in women.[11]

In art

The ancient Greek sculptor Polykleitos (c.450–420 BC), known for his ideally proportioned bronze Doryphoros, wrote an influential Canon describing the proportions to be followed in sculpture.[12] The Canon applies the basic mathematical concepts of Greek geometry, such as the ratio, proportion, and symmetria (Greek for "harmonious proportions") creating a system capable of describing the human form through a series of continuous geometric progressions. Polykleitos uses the distal phalanx of the little finger as the basic module for determining the proportions of the human body, scaling this length up repeatedly by √2 to obtain the ideal size of the other phalanges, the hand, forearm, and upper arm in turn.[13]

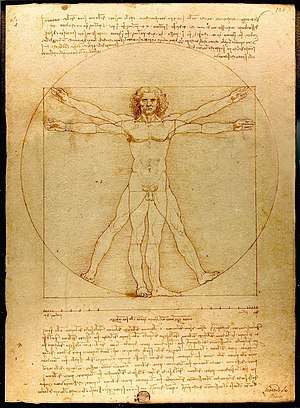

Leonardo da Vinci believed that the ideal human proportions were determined by the harmonious proportions that he believed governed the universe, such that the ideal man would fit cleanly into a circle as depicted in his famed drawing of Vitruvian man (c. 1492).[14]

Leonardo’s recorded information was about relative body proportions – with comparisons of hand, foot, and other feature’s lengths to other body parts – more than to actual measurements. He was a prodigious note writer and small sketch draftsman. After 1490, he left voluminous manuscripts including studies on proportions. These were later collected and translated into English by Jean Paul Richter and published in 1883.[15]

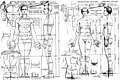

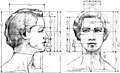

Avard T. Fairbanks taught in five universities. His proportions study was used for college instruction. The main male and female illustrations (1936) were drawn to accompany Leonardo’s system of relative proportions. He erected more than 100 public monuments over the course of his 75 year career. His son, Eugene F. Fairbanks published books based on this study and his own study of children’s proportions.[16]

Additional images

a 1½-year-old child

a 1½-year-old child an adult man

an adult man Human body proportions change with age

Human body proportions change with age Drawings by Avard T. Fairbanks developed during his teaching career. This image was used in Eugene F. Fairbanks' book on Human Proportions for Artists.[17]

Drawings by Avard T. Fairbanks developed during his teaching career. This image was used in Eugene F. Fairbanks' book on Human Proportions for Artists.[17] Avard Fairbanks drawing of proportions of the male head and neck, 1936

Avard Fairbanks drawing of proportions of the male head and neck, 1936 Avard Fairbanks drawing of proportions of the female head and neck, 1936

Avard Fairbanks drawing of proportions of the female head and neck, 1936 Growth and proportions of children, one illustration from Children's Proportions for Artists

Growth and proportions of children, one illustration from Children's Proportions for Artists

Bibliography

- Gottfried Bammes: Studien zur Gestalt des Menschen. Verlag Otto Maier GmbH, Ravensburg 1990, ISBN 3-473-48341-9.

See also

References

- Smith, W. Stevenson, and Simpson, William Kelly. The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt, pp. 12-13 and note 17, 3rd edn. 1998, Yale University Press (Penguin/Yale History of Art), ISBN 0300077475

- Pallett, PM; Link, S; Lee, K (2010). "New "Golden" Ratios for Facial Beauty". Vision Research. 50 (2): 149–54. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2009.11.003. PMC 2814183. PMID 19896961.

- Prokopakis, E. P; Vlastos, I. M; Picavet, V. A; Nolst Trenite, G; Thomas, R; Cingi, C; Hellings, P. W (2013). "The golden ratio in facial symmetry". Rhinology. 51 (1): 18–21. doi:10.4193/Rhino12.111 (inactive 2020-01-22). PMID 23441307.

- Sorokowski, Piotr; Pawlowski, Boguslaw (2008). "Adaptive preferences for leg length in a potential partner". Evolution and Human Behavior. 29 (2): 86–91. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.09.002.

- Sorokowski, Piotr (2017). "Attractiveness of Legs Length in Poland and Great Britain". Journal of Human Ecology. 31 (3): 145–149. doi:10.1080/09709274.2010.11906309.

- Bertamini, Marco; Bennett, Kate M (2009). "The effect of leg length on perceived attractiveness of simplified stimuli". Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology. 3 (3): 233–50. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.163.2823. doi:10.1037/h0099320.

- Frederick, David A; Hadji-Michael, Maria; Furnham, Adrian; Swami, Viren (2010). "The influence of leg-to-body ratio (LBR) on judgments of female physical attractiveness: Assessments of computer-generated images varying in LBR". Body Image. 7 (1): 51–5. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.001. PMID 19822462.

- Swami, Viren; Einon, Dorothy; Furnham, Adrian (2006). "The leg-to-body ratio as a human aesthetic criterion". Body Image. 3 (4): 317–23. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.08.003. PMID 18089235.

- Bogin, B.; Varela-Silva, MI (Mar 2010). "Leg length, body proportion, and health: a review with a note on beauty". Int J Environ Res Public Health. 7 (3): 1047–75. doi:10.3390/ijerph7031047. PMC 2872302. PMID 20617018.

- Chan, Yingleong; Salem, Rany M; Hsu, Yu-Han H; McMahon, George; Pers, Tune H; Vedantam, Sailaja; Esko, Tonu; Guo, Michael H; Lim, Elaine T; Franke, Lude; Smith, George Davey; Strachan, David P; Hirschhorn, Joel N (2015). "Genome-wide Analysis of Body Proportion Classifies Height-Associated Variants by Mechanism of Action and Implicates Genes Important for Skeletal Development". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 96 (5): 695–708. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.02.018. PMC 4570286. PMID 25865494.

- Pope, Harrison; Roberto Olivardia; Amanda Gruber; John Borowiecki (1998-05-26). "Evolving Ideals of Male Body Image as Seen Through Action Toys". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 26 (1): 65–72. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.507.3004. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199907)26:1<65::aid-eat8>3.3.co;2-4. PMID 10349585.

- Stewart, Andrew (November 1978). "Polykleitos of Argos," One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 98: 122–131. doi:10.2307/630196. JSTOR 630196.

- Tobin, Richard (October 1975). "The Canon of Polykleitos". American Journal of Archaeology. 79 (4): 307–321. doi:10.2307/503064. JSTOR 503064.

- "Universal Leonardo: Leonardo Da Vinci Online › Essays." Universal Leonardo: Leonardo Da Vinci Online › Welcome to Universal Leonardo. Web. 22 Apr. 2010. <http://www.universalleonardo.org/essays.php?id=563>.

- Richter, Jean Paul (1970). The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci (Reprint of original 1883 ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-22572-2.

- Faribanks, Eugene F. (2012). Children's Proportions for Artists. Bellingham, WA: Fairbanks Art and Books. ISBN 978-0972584128.

- Fairbanks, Eugene F. (2011). Human Proportions for Artists. Bellingham, WA: Fairbanks Art and Books. ISBN 978-1467901871.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Body proportions. |

- Deriabin, V. E. (1987). "Age-related changes in human body proportions studied by the method of principal components". Nauchnye Doklady Vysshei Shkoly. Biologicheskie Nauki (1): 50–55. PMID 3828410.

- Bogin, B; Varela-Silva, M. I. (2010). "Leg length, body proportion, and health: A review with a note on beauty". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 7 (3): 1047–75. doi:10.3390/ijerph7031047. PMC 2872302. PMID 20617018.

- Chan, Y; Salem, R. M.; Hsu, Y. H.; McMahon, G; Pers, T. H.; Vedantam, S; Esko, T; Guo, M. H.; Lim, E. T.; Giant, Consortium; Franke, L; Smith, G. D.; Strachan, D. P.; Hirschhorn, J. N. (2015). "Genome-wide Analysis of Body Proportion Classifies Height-Associated Variants by Mechanism of Action and Implicates Genes Important for Skeletal Development". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 96 (5): 695–708. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.02.018. PMC 4570286. PMID 25865494.

- Alley, Thomas R. (Feb 1983). "Growth-Produced Changes in Body Shape and Size as Determinants of Perceived Age and Adult Caregiving". Child Development. 54 (1): 241–248. doi:10.2307/1129882. JSTOR 1129882.

- Pittenger, John B. (1990). "Body proportions as information for age and cuteness: Animals in illustrated children's books". Perception & Psychophysics. 48 (2): 124–30. doi:10.3758/BF03207078. PMID 2385485.

- Changing body proportions during growth

.jpg)