Babi Yar

Babi Yar (Ukrainian: Бабин Яр, Babyn Yar or Babin Yar; Russian: Бабий Яр, Babiy Yar) is a ravine in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv and a site of massacres carried out by German forces during their campaign against the Soviet Union in World War II. The first and best documented of the massacres took place on 29–30 September 1941, killing approximately 33,771 Jews. The decision to kill all the Jews in Kyiv was made by the military governor Generalmajor Kurt Eberhard, the Police Commander for Army Group South, SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln, and the Einsatzgruppe C Commander Otto Rasch. Sonderkommando 4a soldiers, along with the aid of the SD and SS Police Battalions with the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police backed by the Wehrmacht carried out the orders.[1][2][3]

| Babi Yar | |

|---|---|

Luftwaffe aerial photograph of Babi Yar, 1943 | |

| Also known as | Babyn Yar, Babi Jar |

| Location | Kiev 50°28′17″N 30°26′56″E |

| Date | 29–30 September 1941 |

| Incident type | Genocide, mass murder |

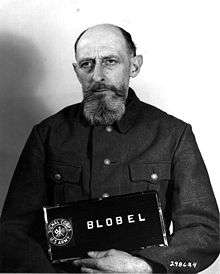

| Perpetrators | Friedrich Jeckeln, Otto Rasch, Paul Blobel, Kurt Eberhard and others |

| Organizations | Einsatzgruppen, Ordnungspolizei, Sonderkommando 4a Wehrmacht |

| Camp | Syrets concentration camp |

| Victims |

|

| Memorials | On site and elsewhere |

| Notes | Possibly the largest two-day massacre during the Holocaust. Syrets concentration camp was also located in the area. Massacres occurred at Babi Yar from 29 September 1941 to 6 November 1943, when Soviet forces liberated Kiev. |

The massacre was the largest mass killing under the auspices of the Nazi regime and its collaborators during its campaign against the Soviet Union[4] and has been called "the largest single massacre in the history of the Holocaust" to that particular date,[5] and surpassed overall only by the later 1941 Odessa massacre of more than 50,000 Jews in October 1941 (committed by German and Romanian troops) and by Aktion Erntefest of November 1943 in occupied Poland with 42,000–43,000 victims.[6]

Victims of other massacres at the site included Soviet prisoners of war, communists, Ukrainian nationalists and Roma.[7][8][9] It is estimated that between 100,000 and 150,000 people were killed at Babi Yar during the German occupation.[10]

Historical background

The Babi Yar (Babyn Yar) ravine was first mentioned in historical accounts in 1401, in connection with its sale by "baba" (an old woman) who was also the cantiniere, to the Dominican Monastery.[11] The word "yar" is Turkic in origin and means "gully" or "ravine". In the course of several centuries the site had been used for various purposes including military camps and at least two cemeteries, among them an Orthodox Christian cemetery and a Jewish cemetery. The latter was officially closed in 1937.

Massacres of 29–30 September 1941

Axis forces, mainly German, occupied Kyiv on 19 September 1941. Between 20 and 28 September, explosives planted by the Soviet secret police caused extensive damage in the city; and on 24 September an explosion rocked Rear Headquarters Army Group South.[12] Two days later, on 26 September, Maj. Gen. Kurt Eberhard, the military governor, and SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln, the SS and Police Leader, met at Rear Headquarters Army Group South. There, they made the decision to exterminate the Jews of Kyiv, claiming that it was in retaliation for the explosions.[13] Also present were SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel, commander of Sonderkommando 4a, and his superior, SS-Brigadeführer Dr. Otto Rasch, commander of Einsatzgruppe C. The mass-killing was to be carried out by units under the command of Rasch and Blobel, who were ultimately responsible for a number of atrocities in Soviet Ukraine during the summer and autumn of 1941.

The implementation of the order was entrusted to Sonderkommando 4a, commanded by Blobel, under the general command of Friedrich Jeckeln.[14] This unit consisted of Sicherheitsdienst (SD) and Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo), the third company of the Special Duties Waffen-SS battalion, and a platoon of the 9th Police Battalion. Police Battalion 45, commanded by Major Besser, conducted the massacre, supported by members of a Waffen-SS battalion. Contrary to the myth of the "clean Wehrmacht", the Sixth Army under the command of Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau worked together with the SS and SD to plan and execute the mass-murder of the Jews of Kyiv.[3]

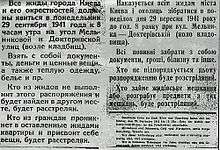

On 26 September 1941 the following order was posted:

All Yids[lower-alpha 1] of the city of Kiev and its vicinity must appear on Monday, September 29, by 8 o'clock in the morning at the corner of Mel'nikova and Dokterivskaya streets (near the Viis'kove cemetery). Bring documents, money and valuables, and also warm clothing, linen, etc. Any Yids[lower-alpha 1] who do not follow this order and are found elsewhere will be shot. Any civilians who enter the dwellings left by Yids[lower-alpha 1] and appropriate the things in them will be shot.

— Order posted in Kyiv in Russian, Ukrainian, and German on or around 26 September 1941.[16]

On 29 and 30 September 1941, the Nazis and their collaborators murdered approximately 33,771 Jewish civilians at Babi Yar.[17][18][19][20] The order to kill the Jews of Kyiv was given to Sonderkommando 4a, of Einsatzgruppe C, consisting of SD and SiPo men, the third company of the Special Duties Waffen-SS battalion, and a platoon of the No. 9 police battalion. These units were reinforced by police battalions Nos. 45 and 305, by units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, and supported by local collaborators.[21]

The commander of the Einsatzkommando reported two days later:[22]

The difficulties resulting from such a large scale action—in particular concerning the seizure—were overcome in Kiev by requesting the Jewish population through wall posters to move. Although only a participation of approximately 5,000 to 6,000 Jews had been expected at first, more than 30,000 Jews arrived who, until the very moment of their execution, still believed in their resettlement, thanks to an extremely clever organization.[23]

According to the testimony of a truck driver named Hofer, victims were ordered to undress and were beaten if they resisted:

I watched what happened when the Jews—men, women and children—arrived. The Ukrainians[lower-alpha 2] led them past a number of different places where one after the other they had to give up their luggage, then their coats, shoes and over-garments and also underwear. They also had to leave their valuables in a designated place. There was a special pile for each article of clothing. It all happened very quickly and anyone who hesitated was kicked or pushed by the Ukrainians [sic][lower-alpha 2] to keep them moving.

— Michael Berenbaum: "Statement of Truck-Driver Hofer describing the murder of Jews at Babi Yar"[26]

The crowd was large enough that most of the victims could not have known what was happening until it was too late; by the time they heard the machine gun fire, there was no chance to escape. All were driven down a corridor of soldiers, in groups of ten, and then shot. A truck driver described the scene.

Once undressed, they were led into the ravine which was about 150 metres long and 30 metres wide and a good 15 metres deep ... When they reached the bottom of the ravine they were seized by members of the Schutzpolizei and made to lie down on top of Jews who had already been shot ... The corpses were literally in layers. A police marksman came along and shot each Jew in the neck with a submachine gun ... I saw these marksmen stand on layers of corpses and shoot one after the other ... The marksman would walk across the bodies of the executed Jews to the next Jew, who had meanwhile lain down, and shoot him.[16]

In the evening, the Germans undermined the wall of the ravine and buried the people under the thick layers of earth.[22] According to the Einsatzgruppe's Operational Situation Report, 33,771 Jews from Kyiv and its suburbs were systematically shot dead by machine-gun fire at Babi Yar on 29 September and 30 September 1941.[27] The money, valuables, underwear, and clothing of the murdered were turned over to the local ethnic Germans and to the Nazi administration of the city.[28] Wounded victims were buried alive in the ravine along with the rest of the bodies.[29]

Survivors

One of the most often-cited parts of Anatoly Kuznetsov's documentary novel Babi Yar is the testimony of Dina Pronicheva, an actress of the Kyiv Puppet Theatre, and a survivor.[30] She was one of those ordered to march to the ravine, to be forced to undress and then be shot. Jumping before being shot and falling on other bodies, she played dead in a pile of corpses. She held perfectly still while the Nazis continued to shoot the wounded or gasping victims. Although the SS had covered the mass grave with earth, she eventually managed to climb through the soil and escape. Since it was dark, she had to avoid the torches of the Nazis finishing off the remaining victims still alive, wounded and gasping in the grave. She was one of the very few survivors of the massacre and later related her story to Kuznetsov.[31] At least 29 survivors are known.[32]

In 2006, Yad Vashem and other Jewish organisations started a project to identify and name the Babi Yar victims, but so far only 10% have been identified. Yad Vashem has recorded the names of around 3,000 Jews killed at Babi Yar, as well as those of some 7,000 Jews from Kyiv who were killed during the Holocaust.[33]

Further massacres

In the months that followed, thousands more were seized and taken to Babi Yar where they were shot. It is estimated that more than 100,000 residents of Kyiv of all ethnic groups,[34][35][36][37][38] mostly civilians, were murdered by the Nazis there during World War II.[17][39] A concentration camp was also built in the area.

Mass executions at Babi Yar continued until the Nazis evacuated the city of Kyiv. On 10 January 1942 about 100 captured Soviet sailors were executed there after being forced to disinter and cremate the bodies of previous victims. In addition, Babi Yar became a place of execution of residents of five Gypsy camps. Patients of the Ivan Pavlov Psychiatric Hospital were gassed and then dumped into the ravine. Thousands of other Ukrainians were killed at Babi Yar.[40] Among those murdered were 621 members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN).[8] Ukrainian poet and activist Olena Teliha and her husband, and renowned bandurist Mykhailo Teliha, were murdered there on 21 February 1942.[9] Also killed in 1941 was Ukrainian activist writer Ivan Rohach, his sister, and his staff.

Upon the Soviet liberation of Kyiv in 1943, Soviet officials led Western journalists to the site of the massacres and allowed them to interview survivors. Among them were Bill Lawrence of The New York Times and Bill Downs of CBS. Downs described in a report to Newsweek what he had been told by one of the survivors, Efim Vilkis:

However, even more incredible was the actions taken by the Nazis between August 19 and September 28 last. Vilkis said that in the middle of August the SS mobilized a party of 100 Russian war prisoners, who were taken to the ravines. On August 19 these men were ordered to disinter all the bodies in the ravine. The Germans meanwhile took a party to a nearby Jewish cemetery whence marble headstones were brought to Babii Yar [sic] to form the foundation of a huge funeral pyre. Atop the stones were piled a layer of wood and then a layer of bodies, and so on until the pyre was as high as a two-story house. Vilkis said that approximately 1,500 bodies were burned in each operation of the furnace and each funeral pyre took two nights and one day to burn completely. The cremation went on for 40 days, and then the prisoners, who by this time included 341 men, were ordered to build another furnace. Since this was the last furnace and there were no more bodies, the prisoners decided it was for them. They made a break but only a dozen out of more than 200 survived the bullets of the Nazi machine guns.[41]

Numbers murdered

Estimates of the total number killed at Babi Yar during the Nazi occupation vary. In 1946, Soviet prosecutor L. N. Smirnov at the Nuremberg trials claimed there were approximately 100,000 corpses lying in Babi Yar, using materials of the Extraordinary State Commission set out by the Soviets to investigate Nazi crimes after the liberation of Kyiv in 1943.[39][42][43][44] According to testimonies of workers forced to burn the bodies, the numbers range from 70,000 to 120,000.

In a recently published letter to Israeli journalist, writer and translator Shlomo Even-Shoshan dated 17 May 1965, Anatoly Kuznetsov commented on the Babi Yar atrocity:

In the two years that followed, Ukrainians, Russians, Gypsies and people of all nationalities were murdered in Babi Yar. The belief that Babi Yar is an exclusively Jewish grave is wrong... It is an international grave. Nobody will ever determine how many and what nationalities are buried there, because 90% of the corpses were burned, their ashes scattered in ravines and fields.[45]

For his war crimes, Paul Blobel was sentenced to death by the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials in the Einsatzgruppen Trial. He was hanged on 7 June 1951 at Landsberg Prison.[46]

Syrets concentration camp

_Kiev.jpg)

In the course of the German occupation, the Syrets concentration camp was set up in Babi Yar. Interned communists, Soviet prisoners of war (POWs), and captured resistance members were murdered there, among others. On 18 February 1943, three Dynamo Kyiv football players (Trusevich, Klimenko, and Putistin) who took part in the Match of Death with the German Luftwaffe team were also murdered in the camp.[47]

Concealment of the crimes

Before the Nazis retreated from Kyiv ahead of the Soviet offensive of 1944, they were ordered by Wilhelm Koppe to conceal their atrocities in the East. Paul Blobel, who had been in control of the mass murders in Babi Yar two years earlier, supervised the Sonderaktion 1005 in eliminating its traces. The Aktion was carried out earlier in all extermination camps. The bodies were exhumed, burned and the ashes scattered over farmland in the vicinity.[48][49] Several hundred prisoners of war from the Syrets concentration camp were forced to build funeral pyres out of Jewish gravestones and exhume the bodies for cremation.[50]

Remembrance

After the war, specifically Jewish commemoration efforts encountered serious difficulty because of the Soviet Union's policies.[51] Yevtushenko's 1961 poem on Babi Yar begins "Nad Babim Yarom pamyatnikov nyet" ("There are no monuments over Babi Yar"); it is also the first line of Shostakovitch's Symphony No. 13.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a number of memorials have been erected on the site and elsewhere. The events also formed a part of literature. Babi Yar is located in Kyiv at the juncture of today's Kurenivka, Lukianivka and Syrets districts, between Kyrylivska, Melnykov and Olena Teliha streets and St. Cyril's Monastery. After the Orange Revolution, President Viktor Yushchenko of Ukraine hosted a major commemoration of the 65th anniversary in 2006, attended by Presidents Moshe Katsav of Israel, Filip Vujanovic of Montenegro, Stjepan Mesić of Croatia and Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau. Rabbi Lau pointed out that if the world had reacted to the massacre of Babi Yar, perhaps the Holocaust might never have happened. Implying that Hitler was emboldened by this impunity, Lau speculated:

Maybe, say, this Babi Yar was also a test for Hitler. If on 29 September and 30 September 1941 Babi Yar may happen and the world did not react seriously, dramatically, abnormally, maybe this was a good test for him. So a few weeks later in January 1942, near Berlin in Wannsee, a convention can be held with a decision, a final solution to the Jewish problem... Maybe if the very action had been a serious one, a dramatic one, in September 1941 here in Ukraine, the Wannsee Conference would have come to a different end, maybe.[52]

In 2006, a message was also delivered on behalf of Kofi Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations,[53] by his representative, Resident Coordinator Francis Martin O'Donnell, who added a Hebrew prayer O'seh Shalom,[54] from the Mourners' Kaddish.

Mudslide

Babi Yar was also the site of a large mudslide in the spring of 1961. An earthen dam in the ravine had held loam pulp that had been pumped from the local brick factories for ten years without sufficient drainage. The dam collapsed after heavy rain, inundating the lower-lying Kurenivka neighborhood. The death toll was estimated to be between 1,500 and 2,000 people.[55] According to Kusnetsov, this was part of a sustained and massive effort of the Soviets to obliterate the site, including what remained of the old Jewish burying ground.

See also

- Babi Yar in poetry

- Symphony No. 13, called Babi Yar, by Dmitri Shostakovich

- Symphony No.1 In Memoriam to the Martyrs of Babi Yar by Dmitri Klebanov (1945, audio)

- Babi Yar Holocaust Memorial Center

- Consequences of Nazism

- Genocides in history

- History of the Jews in Ukraine

- List of massacres in Ukraine

- Mass graves in the Soviet Union

- Operation Barbarossa

- Reichskommissariat Ukraine

- Ukrainian collaborationism with the Axis powers

- Nazi crimes against Soviet POWs

- The Kindly Ones

Notes

- The order was posted in German, Ukrainian, and in the largest letters, Russian. In only the Russian version is the defamatory word "Zhid" used for Jews. The respectful Russian word is "Yevrey". Ukrainian and Russian are not the same language. The word "zhyd" in Ukrainian is not defamatory at all, as noted by Nikita Khrushchev in his memoirs, "I remember that once we invited Ukrainians, Jews and Poles ... to a meeting at the Lvov [Lviv] opera house. It struck me as very strange to hear the Jewish speakers at the meeting refer to themselves as 'yids.' 'We yids hereby declare ourselves in favour of such-and-such.' Out in the lobby after the meeting I stopped some of these men and demanded, 'How dare you use the word "yid?" Don't you know it's a very offensive term, an insult to the Jewish nation?' 'Here in the Western Ukraine it's just the opposite,' they explained. 'We call ourselves yids' ... Apparently what they said was true. If you go back to Ukrainian literature...you'll see that 'yid' isn't used derisively or insultingly."[15]

- It must be noted that while the witness referred to "[t]he Ukrainians" there has only been one documented Ukrainian speaker at Babi Yar, and that was Second Lieutenant Joseph Muller, an ethnic German from Galicia.[24] Thus, it is more accurate to describe these people as "Ukrainian speakers". A German policeman who guarded Babi Yar testified in 1965 that "the Jews were guarded by Wehrmacht units and by a Hamburg Police Battalion, which, as far as I can remember, carried the number 303."[25]

References

- Karel C. Berkhoff (May 28, 2008). "Babi Yar Massacre". The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization. p. 303. ISBN 0253001595. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- "Holocaust in Kiev and the Tragedy of Babi Yar | www.yadvashem.org". historical-background3.html. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- Wette, Wolfram (2005). Die Wehrmacht : Feindbilder, Vernichtungskrieg, Legenden (Überarb. Ausg. ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verl. pp. 115–128. ISBN 3596156459.

- Wolfram Wette (2006). The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Harvard University Press. p. 112.

- Wendy Lower, "From Berlin to Babi Yar. The Nazi War Against the Jews, 1941–1944" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2014-04-24.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Journal of Religion & Society, Volume 9 (2007). The Kripke Center, Towson University. I.S.S.N 1522–5658. Retrieved from Internet Archive, May 24, 2013.

- Browning, Christopher R. (1992–1998). "Arrival in Poland" (PDF file, direct download 7.91 MB complete). Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Penguin Books. pp. 135–142. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- Hoffman, Avi (23 October 2011). "A Museum for Babi Yar". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 2013-06-26.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-12-27. Retrieved 2014-12-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Zionism and Israel - Encyclopedic Dictionary - Babi Yar

- Ludmyla Yurchenko, "Life is not to be sold for a few pieces of silver: The life of Olena Teliha Archived 2007-08-14 at the Wayback Machine", Ukrainian Youth Association.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-8020-7820-9.

- Anatoliy Kudrytsky, editor-in-chiev, "Vulytsi Kyeva" (The Streets of Kiev), Ukrainska Entsyklopediya , ISBN 5-88500-070-0

- "Remembering the Kyiv Inferno, 1941". Kyiv Post. September 25, 2016.

-

- Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2006). War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-7425-4481-9.

- Murray, Williamson; Millett, Allan R. (2001). A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War. Harvard University Press. p. 141. ISBN 0-674-00680-1.

- 1941: Mass Murder Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine The Holocaust Chronicle. p. 270

- Khrushchev, Nikita (1971). Khrushchev Remembers. New York: Bantam Books. p. 145.

- Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, this edition 2006, pp. 97–98.

- "Kiev and Babi Yar". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-01-03.

- Prusin, Alexander V. (Spring 2007). "A Community of Violence: The SiPo/SD and Its Role in the Nazi Terror System in Generalbezirk Kiew". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 21: 1–30. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcm001.

- "The Holocaust Chronicle: Massacre at Babi Yar". The Holocaust Chronicle. Archived from the original (web site) on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- Victoria Khiterer (2004). "Babi Yar: The tragedy of Kiev's Jews" (PDF). Brandeis Graduate Journal. 2: 1–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-11-28. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- Gutman, Israel (1990). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, vol. 1. Macmillan. pp. 133–6.

- Gilbert, Martin (1985). The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 202. ISBN 0-03-062416-9.

- Nuremberg Military Tribunal, Einsatzgruppen trial, Judgment, at page 426, quoting exhibit NO-3157.

- "The dark secrets of Babi Yar". kyivpost.com. 2 October 1998. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Longerich, Peter, ed. (1989). Die Ermordung der euopäischen Juden: Eine umfassende Dokumentation der Holocaust 1941–1945. Munich and Zurich. p. 123.

- ""Statement of Truck-Driver Hofer describing the murder of Jews at Babi Yar"". Archived from the original on 2007-06-06. Retrieved 2006-01-09. cited in Berenbaum, Michael (1997). Witness to the Holocaust. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 138–139.

- Operational Situation Report No. 101 Archived 2006-12-07 at the Wayback Machine (einsatzgruppenarchives.com)

- Nuremberg Military Tribunal, Einsatzgruppen trial, Judgment, at page 430.

- Lawrence, Bill (1972). Six Presidents, Too Many Wars. New York: Saturday Review Press. p. 93.

- Ray Brandon; Wendy Lower (2008). The Shoah in Ukraine: history, testimony, memorialisation. Indiana University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-253-35084-8.

- "A Survivor of the Babi Yar Massacre Archived 2008-03-14 at the Wayback Machine," Heritage: Civilization and the Jews (PBS). Gilbert (1985): 204–205.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-02-17. Retrieved 2008-02-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Amiram Barkat and Haaretz Correspondent (September 2006). "Yad Vashem tries to name Babi Yar victims, but only 10% identified". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- "Бабин Яр: два дні — два роки — двадцяте століття /ДЕНЬ/". Day.kiev.ua. 2007-11-28. Archived from the original on 2005-04-05. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- Юрій Шаповал (February 27, 2009),""Бабин Яр": доля тексту та автора". Archived from the original on 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2010-08-28.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Літакцент, 2007-2009.

- Yury Shapoval, "The Defection of Anatoly Kuznetsov", День, January 18, 2005.

- "Бабин яр – Бабий яр – Babij jar – Babyn jar". 1000years.uazone.net. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- "Kiev and Babi Yar". Ushmm.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-19. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- Shmuel Spector, "Babi Yar," Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Israel Gutman, editor in chief, Yad Vashem, Sifriat Hapoalim, New York: Macmillan, 1990. 4 volumes. ISBN 0-02-896090-4. An excerpt of the article is available at Ada Holtzman, "Babi Yar: Killing Ravine of Kiev Jewry – WWII Archived 2012-12-30 at the Wayback Machine", We Remember! Shalom!.

- Babi Yar (Page 2) Archived 2007-06-11 at the Wayback Machine by Jennifer Rosenberg (about.com)

- Downs, Bill (December 6, 1943). "Blood at Babii Yar - Kiev's Atrocity Story". Newsweek: 22.

- Materials of the Nuremberg Trial in Russian: Нюрнбергский процесс, т. III. M., 1958. с. 220–221.

- Iosif Kremenetsky, "Babi Yar – September 1941" Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- Из Сообщения Чрезвычайной Государственной Комиссии о Разрушениях и зверствах, Совершенных Немецко – Фашистскими Захватчиками в Городе Киеве. Archived 2007-12-06 at the Wayback Machine Нюрнбергский Процесс. Документ СССР-9. (in Russian)

- Yury Shapoval, "The Defection of Anatoly Kuznetsov" Archived January 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, День, January 18, 2005.

- Earl, Hilary Camille (2009). The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial, 1945-1958: Atrocity, Law, and History. Cambridge University Press. p. 293.

- ARC (July 9, 2006). "The KZ in Syrets". Occupation of the East. Deathcamps.org. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Aktion 1005. Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- Aktion 1005. Archived 2015-11-08 at the Wayback Machine Yad Vashem. Shoa Resource Centre. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- Lawrence, Bill (1972). Six Presidents, Too Many Wars. New York: Saturday Review Press. p. 94.

- Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 by Tony Judt, Penguin Books, Reprint edition (September 5, 2006),ISBN 0143037757 (page 182)

- "Rabbi Lau's Statement at the International Forum "''Let My People Live!''", Kiev, September 27, 2006; World Holocaust Forum". Worldholocaustforum.org. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- 27.09.2006 (2006-09-27). "Message of Kofi Annan, UN Secretary General, delivered by Francis O'Donnell, UN Resident Coordinator in Ukraine". Worldholocaustforum.org. Archived from the original on 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2012-03-07.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Full text with post-script by O'Donnell". Un.org.ua. 2006-09-27. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- Smoliy, V. A.; Goryak, G. V.; Danilenko, V. M. (2012). Куренівська трагедія 13 березня 1961 р. у Києві: причини, обставини, наслідки. Документи і матеріали. Institute of Ukrainian History NAN Ukraine. p. 18. ISBN 978-966-02-6392-5. Archived from the original on 2017-09-28. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

Sources

- A. Anatoli (Anatoly Kuznetsov), trans. David Floyd, (1970), Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel, Jonathan Cape Ltd. ISBN 0-671-45135-9

- "Babi Yar in the mirror of science, or the map of Bermuda Triangle", an article in Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), July 2005, available online in Russian and in Ukrainian

- Encyclopedia of Kyiv

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Babi Yar. |

- The Invasion of the Soviet Union and the Beginnings of Mass Murder on the Yad Vashem website

- Marking 70 Years to Operation Barbarossa on the Yad Vashem website

- Babi Yar: Mass Murder (history1900s.about.com)

- In-depth study on Babi Yar

- The Massacre at Babi Yar Near Kyiv (historyplace.com)

- Babi Yar (Jewish Virtual Library)

- Babi Yar: Killing Ravine of Kyiv Jewry – WWII (zchor.org)

- Babi Yar (berdichev.org)

- (in Russian) History. Geography. Memory by Tatyana Yevstafyeva. August 15, 2002 (a reprint from newspaper "Jewish Observer")