And Then There Were None

And Then There Were None is a mystery novel by English writer Agatha Christie, described by her as the most difficult of her books to write.[2] It was first published in the United Kingdom by the Collins Crime Club on 6 November 1939, as Ten Little Niggers,[3] after the minstrel song, which serves as a major plot point.[4][5]

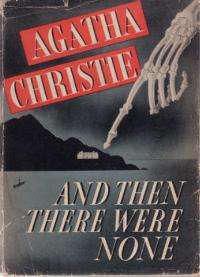

Cover of first US 1940 edition with current title for all English-language versions | |

| Author | Agatha Christie |

|---|---|

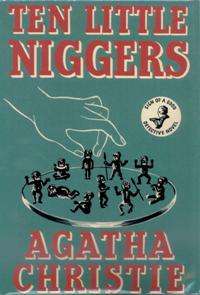

| Original title | Ten Little Niggers |

| Cover artist | Stephen Bellman |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Mystery, crime, psychological thriller, horror |

| Publisher | Collins Crime Club |

Publication date | 6 November 1939 |

| Pages | 272[1] |

| Preceded by | Murder Is Easy |

| Followed by | Sad Cypress |

| Website | And Then There Were None |

The US edition was released in January 1940 with the title And Then There Were None, which is taken from the last five words of the song.[6] All successive American reprints and adaptations use that title, except for the Pocket Books paperbacks published between 1964 and 1986, which appeared under the title Ten Little Indians.

The book is the world's best-selling mystery, and with over 100 million copies sold is one of the best-selling books of all time. Publications International lists the novel as the sixth best-selling title.[7]

Plot summary

On 8 August in the late 1930s, eight people arrive on a small, isolated island off the Devon coast of England. Each has an invitation tailored to their personal circumstances, such as an offer of employment or an unexpected late summer holiday. They are met by Thomas and Ethel Rogers, the butler and cook-housekeeper, who state that their hosts, Mr. Ulick Norman Owen and his wife Mrs. Una Nancy Owen, whom they have not yet met in person, have not arrived, but left instructions, which strikes all the guests as odd.

A framed copy of a nursery rhyme, "Ten Little Niggers"[8] (called "Ten Little Indians" or "Ten Little Soldiers" in later editions), hangs in every guest's room, and ten figurines sit on the dining room table. After supper, a gramophone (or "phonograph") record is played; the recording accuses each visitor of having committed murder, and then asks if any of "the accused" wishes to offer a defence. Anthony Marston and Philip Lombard admit to the charges leveled against them, both instances of irresponsible endangerment resulting in death rather than murder as normally defined.

They discover that none of them actually knows the Owens, and Justice Wargrave concludes that the name "U N Owen" is a play on "Unknown". Marston finishes his drink and immediately dies from cyanide poisoning. Dr. Armstrong confirms that there is no cyanide in the drinks Marston was served from, indicating he committed suicide.

The next morning, Mrs. Rogers' corpse is found in her bed; she died in her sleep. The cause is unknown, but some of the guests suspect her husband of poisoning her for fear that she would confess to the crime they are charged with in the recording. By lunchtime, General MacArthur is found dead, from a heavy blow to his head. Three of the figurines are found to be broken, and again the deaths parallel the rhyme.

The guests begin to suspect that U N Owen is systematically murdering them. A search for Owen turns up no results. The island is a "bare rock" with no hiding places, and no one could have arrived or left; thus, they conclude that one of the seven remaining persons is the killer. Wargrave leads the group in determining that so far, none of them can definitively be ruled out as the murderer. The next morning, Rogers is found dead while chopping wood. After breakfast, Emily Brent is found dead in the kitchen, where she had been left alone after complaining of feeling unwell; she had been injected with potassium cyanide via a hypodermic needle.

Wargrave suggests searching all the rooms, and any potentially dangerous items are locked up. Lombard's gun is missing from his room. When Vera goes upstairs to take a bath, she is shocked by the touch and smell of seaweed left hanging from the ceiling of her room and screams; the remaining guests rush upstairs to her room. Wargrave, however, is still downstairs. The others find him seated, immobile and crudely dressed up in the attire of a judge. Wargrave is examined by Armstrong and pronounced dead from a gunshot to the forehead.

That night, Lombard finds his gun returned to his room. Henry Blore catches a glimpse of someone leaving the house but loses the trail. Only Armstrong is absent from his room. Vera, Blore, and Lombard decide to stay together at all times. In the morning, they signal SOS to the mainland from outside by using a mirror and sunlight, but receive no reply. Blore returns to the house for food by himself and is killed by a heavy bear-shaped clock statue that is pushed from Vera's window sill, crushing his skull. Since neither of them were near the house when the death occurred, Vera and Lombard conclude that Armstrong is the killer.

Vera and Lombard come upon Armstrong's body washed up on the beach. Each concludes the other must be the killer. Vera suggests moving the doctor's body past the shore as a gesture of respect for the dead, but this is a pretext. While they move the body, she lifts Lombard's gun. When Lombard lunges at her to get it back, she shoots him dead.

She returns to the house in a shaken dreamlike state, relieved to be alive. She finds a noose and chair arranged in her room, and a strong smell of the sea. Pressed by guilt over the crime she is accused of - causing the drowning of a boy in her charge because he held priority over her lover for his inheritance - she hangs herself in accordance with the last verse of the rhyme.

Scotland Yard officials are puzzled at who could have killed the ten. They reconstruct the deaths from Marston to Wargrave with the help of the victims' diaries and a coroner's report, and systematically determine that none of the last four victims (Armstrong, Blore, Lombard, or Claythorne) can be the killer, since there was some form of cleanup following all their deaths except Blore's (for example, the chair on which Vera stood to hang herself had been set back upright), and a suicide by falling clock seems beyond the realm of probability. Isaac Morris, a sleazy lawyer and drug trafficker, purchased the island, arranged the invitations, ordered the production of the gramophone record, and told the inhabitants of nearby Sticklehaven to ignore any signals for help, citing a bet about living on a "desert island" for a week. However, Morris died of an overdose of barbiturates on the night of 8 August.

A fishing ship picks up a bottle inside its trawling nets; the bottle contains a written confession of the killings, which is then sent to Scotland Yard. In the confession, Justice Wargrave writes that all his life he has had two contradictory impulses: a savage bloodlust and a strong sense of justice. For most of his life, he satisfied both desires through his profession as judge. However, the desire to commit murder with his own hands and his diagnosis with a terminal illness motivated him to orchestrate a mass murder of people who were themselves murderers by his judgment but could not be prosecuted under the law. Before departing for the island, he gave Morris barbiturates to take for his indigestion. He tricked Armstrong into helping him fake his own death under the pretext that it would help the group identify the killer. He used the gun and some elastic to ensure his true death matched the account in the guests' diaries. Although he wished to create an unsolvable mystery, he acknowledges in the missive a "pitiful human need" for recognition, hence the confession.

Characters

The following details of the characters are based on the original novel published in England.

- Anthony James Marston, a handsome but amoral and irresponsible young man, who killed two young children (John and Lucy Combes) while driving recklessly while drunk, for which he feels no remorse and accepts no personal responsibility, complaining only that his driving licence had been suspended as a result. He is the first island victim, having his drink poisoned and suffocating. ("One choked his little self...")

- Mrs Ethel Rogers, the cook/housekeeper and Thomas Rogers' wife, described as a pale and ghost-like woman who walks in mortal fear. She is dominated by her bullying husband, who coerces her into withholding the medicine of a former employer (Miss Jennifer Brady, an elderly spinster) in order that they might collect an inheritance they knew she had left them in her will. Mrs Rogers was haunted by the crime for the rest of her life, and is the second victim, dying in her sleep. ("One overslept himself...")

- General John Gordon MacArthur, a retired World War I war hero, who sent his late wife's lover (a younger officer, Arthur Richmond) to his death by assigning him to a mission where it was practically guaranteed he would not survive. Leslie MacArthur had mistakenly put the wrong letters in the envelopes on one occasion when she wrote to both men at the same time. The general tells Vera that no one will leave the island alive. ("One said he'd stay there...")

- Thomas Rogers, the butler and Ethel Rogers' husband. He dominates his weak-willed wife, and they killed their former employer by withholding her medicine, causing the woman to die from heart failure, thus inheriting the money she bequeathed them in her will. Despite his wife's death, Rogers continues serving the others, and is killed with an axe while chopping wood. ("One chopped himself in half...")

- Emily Caroline Brent, an elderly, pious spinster who accepts the vacation on Soldier Island largely due to financial constraints. Years earlier, she had dismissed her teenage maid, Beatrice Taylor, for becoming pregnant out of wedlock. Beatrice, who had already been rejected by her parents for the same reason, drowned herself, which Miss Brent considered an even worse sin. The murderer puts a bee into the room, in addition to murder by poison. ("A bumblebee stung one...")

- Dr Edward George Armstrong, a Harley Street doctor, responsible for the death of a patient, Louisa Mary Clees, after he operated on her while drunk many years earlier. He is tricked by Wargrave into meeting him on a clifftop above the sea and pushed over, where he drowns. ("A red herring swallowed one...")

- William Henry Blore, a former police inspector and now a private investigator, was accused of falsifying his testimony in court for a bribe from a dangerous criminal gang, which resulted in an innocent man, James Landor, being convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. Landor, who had a wife and young child, died shortly afterwards in prison. Blore arrives under the alias "Davis" from South Africa, on the island for "security work." His true name is revealed on the gramophone recording. He denies the accusation against him from the gramophone recording, but later admits the truth to Lombard. He is crushed to death by a brass bear clock. ("A big bear hugged one...")

- Philip Lombard, a soldier of fortune. He is literally down to his last square meal when he meets Isaac Morris, who makes the proposition which brings Lombard to the island. He carries a loaded revolver, as Morris had hinted he might wish to do. Lombard is accused of causing the deaths of a number of East African tribesmen, after stealing their food and abandoning them to their deaths. Neither he nor Marston feels any remorse. He is the only one to theorize that Wargrave might be “U N Owen”, but the others dismiss the idea. He and Vera are the only victims not killed by Justice Wargrave, as Vera shoots him on the beach. ("One got all frizzled up...")

- Vera Elizabeth Claythorne, a cool, efficient, resourceful young woman who is on leave from her position as a sports mistress at a third-rate girls' school. She was once a governess employed by the wealthy Hamilton family, but was quietly fired after her young charge, Cyril, drowned on her watch. It is later revealed that she let the boy drown so his uncle Hugo could inherit the family estate and marry her. Hugo rejected her when he realized what she had done. In a post-traumatic state after shooting Lombard, finding a waiting noose in her room, she hangs herself. ("One went and hanged himself...")

- Justice Lawrence John Wargrave, a retired judge, known as a "hanging judge" for liberally awarding the death penalty in murder cases. Wargrave is accused of influencing the jury to hand a guilty verdict to Edward Seton, a man many thought was innocent of his crime of killing an old woman, and sentencing him to death unfairly. As the two policemen discuss at Scotland Yard, new evidence after Seton's execution proved Seton's guilt. Wargrave admits in his postscript that he has always harbored homicidal urges, but his sense of justice prevented him from acting on them; he thus sentences guilty defendants to death as a means of satisfying these contradictory impulses. When he is diagnosed with a terminal illness, he devises and carries out a plot to kill a group of people he believes deserve it. His false death is sixth, corresponding to the line "One got in Chancery..."

- Isaac Morris is a sleazy, unethical lawyer and erstwhile drug trafficker hired by Wargrave to purchase the island (under the name “UN Owen”), arrange the gramophone recording, and make arrangements on his behalf, including gathering information on the near destitute Philip Lombard, to whom he gave some money to get by and recommended Lombard bring his gun to the island. Morris' is the first death chronologically, as he dies before the guests arrive on the island. Years earlier, Morris had sold narcotics to the daughter of one of Wargrave’s friends; she became an addict, and later committed suicide. A hypochondriac, Morris accepts a lethal cocktail of pills from Wargrave to help treat his largely imagined physical ailments.

- Fred Narracott, the boatman who delivers the guests to the island. After doing so, he does not appear again in the story, although Inspector Maine notes it was Narracott who, sensing something seriously amiss, returned to the island as soon as the weather allowed, before he was scheduled to do so, and found the bodies. Maine speculates that it was the normalcy and ordinariness of the guests that convinced Narracott to do so and ignore his orders to dismiss any signals requesting help.

- Sir Thomas Legge and Inspector Maine, two Scotland Yard detectives who discuss the case in the epilogue. They reason out the events of the case, but are stymied as to who was the murderer until the confession comes to light.

Literary significance and reception

Writing for The Times Literary Supplement of 11 November 1939, Maurice Percy Ashley stated, "If her latest story has scarcely any detection in it there is no scarcity of murders... There is a certain feeling of monotony inescapable in the regularity of the deaths which is better suited to a serialized newspaper story than a full-length novel. Yet there is an ingenious problem to solve in naming the murderer", he continued. "It will be an extremely astute reader who guesses correctly."[9]

For The New York Times Book Review (25 February 1940), Isaac Anderson has arrived to the point where "the voice" accuses the ten "guests" of their past crimes, which have all resulted in the deaths of humans, and then said, "When you read what happens after that you will not believe it, but you will keep on reading, and as one incredible event is followed by another even more incredible you will still keep on reading. The whole thing is utterly impossible and utterly fascinating. It is the most baffling mystery that Agatha Christie has ever written, and if any other writer has ever surpassed it for sheer puzzlement the name escapes our memory. We are referring, of course, to mysteries that have logical explanations, as this one has. It is a tall story, to be sure, but it could have happened."[10]

Many compared the book to her novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926). For instance, an unnamed reviewer in the Toronto Daily Star of 16 March 1940 said, "Others have written better mysteries than Agatha Christie, but no one can touch her for ingenious plot and surprise ending. With And Then There Were None... she is at her most ingenious and most surprising... is, indeed, considerably above the standard of her last few works and close to the Roger Ackroyd level."[11]

Other critics laud the use of plot twists and surprise endings. Maurice Richardson wrote a rhapsodic review in The Observer's issue of 5 November 1939 which began, "No wonder Agatha Christie's latest has sent her publishers into a vatic trance. We will refrain, however, from any invidious comparisons with Roger Ackroyd and be content with saying that Ten Little Niggers is one of the very best, most genuinely bewildering Christies yet written. We will also have to refrain from reviewing it thoroughly, as it is so full of shocks that even the mildest revelation would spoil some surprise from somebody, and I am sure that you would rather have your entertainment kept fresh than criticism pure." After stating the set-up of the plot, Richardson concluded, "Story telling and characterisation are right at the top of Mrs Christie's baleful form. Her plot may be highly artificial, but it is neat, brilliantly cunning, soundly constructed, and free from any of those red-herring false trails which sometimes disfigure her work."[3]

Robert Barnard, a recent critic, concurred with the reviews, describing the book as "Suspenseful and menacing detective-story-cum-thriller. The closed setting with the succession of deaths is here taken to its logical conclusion, and the dangers of ludicrousness and sheer reader-disbelief are skillfully avoided. Probably the best-known Christie, and justifiably among the most popular."[12]

The original title of the mystery (Ten Little Niggers) was changed because it was offensive in the United States and some other places. Alison Light, a literary critic and feminist scholar, opined that Christie's original title and the setting on "Nigger Island" (later changed to "Indian Island" and "Soldier Island", variously) were integral to the work. These aspects of the novel, she argued, "could be relied upon automatically to conjure up a thrilling 'otherness', a place where revelations about the 'dark side' of the English would be appropriate."[13] Unlike novels such as Heart of Darkness, "Christie's location is both more domesticated and privatized, taking for granted the construction of racial fears woven into psychic life as early as the nursery. If her story suggests how easy it is to play upon such fears, it is also a reminder of how intimately tied they are to sources of pleasure and enjoyment."[13]

In the "Binge!" article of Entertainment Weekly Issue #1343-44 (26 December 2014–3 January 2015), the writers picked And Then There Were None as an "EW favorite" on the list of the "Nine Great Christie Novels".[14]

Current published version of the rhyme

Ten little Soldier Boys went out to dine;

One choked his little self and then there were nine.

Nine little Soldier Boys sat up very late;

One overslept himself and then there were eight.

Eight little Soldier Boys travelling in Devon;

One said he'd stay there and then there were seven.[15]

Seven little Soldier Boys chopping up sticks;

One chopped himself in halves and then there were six.

Six little Soldier Boys playing with a hive;

A bumblebee stung one and then there were five.

Five little Soldier Boys going in for law;

One got in Chancery and then there were four.

Four little Soldier Boys going out to sea;

A red herring swallowed one and then there were three.

Three little Soldier Boys walking in the zoo;

A big bear hugged one and then there were two.

Two little Soldier Boys sitting in the sun;

One got frizzled up and then there was one.[16]

One little Soldier Boy left all alone;

He went out and hanged himself and then there were none.[17]

19th-century original verses

This children's rhyme was originally written as songs in the 19th century, one in Britain in 1869[18] and one in the US in 1868.[19]

- 1869 & 1868 verses

| Ten Little Niggers (Frank Green)[18] |

Ten Little Indians (Septimus Winner)[19] |

|---|---|

|

Ten little nigger boys went out to dine Nine little nigger boys sat up very late Eight little nigger boys traveling in Devon Seven little nigger boys chopping up sticks Six little nigger boys playing with a hive Five little nigger boys going in for law Four little nigger boys going out to sea Three little nigger boys walking in the zoo Two little nigger boys sitting in the sun One little nigger boy living all alone |

Ten little Injuns standin' in a line, Nine little Injuns swingin' on a gate,

Eight little Injuns gayest under heav'n, Seven little Injuns cutting up their tricks, Six little Injuns kickin' all alive, Five little Injuns on a cellar door, Four little Injuns up on a spree, Three little Injuns out in a canoe, Two little Injuns foolin' with a gun, One little Injun livin' all alone, |

Publication history

This novel has a long and noteworthy history of publication. It is a continuously best selling novel in English and in translation to other languages since its initial publication. From the start, in English, it was published under two different titles, due to different sensitivity to the author's title and counting-rhyme theme in the UK and in the US at first publication.

The title

The novel was originally published in late 1939 and early 1940 almost simultaneously, in the United Kingdom and the United States. In the UK it appeared under the title Ten Little Niggers, in book and newspaper serialized formats. The serialization was in 23 parts in the Daily Express from Tuesday 6 June to Saturday 1 July 1939. All of the instalments carried an illustration by "Prescott" with the first having an illustration of Burgh Island in Devon which inspired the setting of the story. The serialized version did not contain any chapter divisions.[20] The book retailed for seven shillings and six pence.

In the United States it was published under the title And Then There Were None, in both book and serial formats. Both of the original US publications changed the title from that originally used in the UK, due to the offensiveness of the word in American culture, where it was more widely perceived as a racially loaded ethnic slur or insult compared to the contemporaneous culture in the United Kingdom. The serialized version appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in seven parts from 20 May (Volume 211, Number 47) to 1 July 1939 (Volume 212, Number 1) with illustrations by Henry Raleigh, and the book was published in January 1940 by Dodd, Mead and Company for $2.[4][5][6]

In the original UK novel, and in succeeding publications until 1985, all references to "Indians" or "Soldiers" were originally "Nigger", including the island's name, the pivotal rhyme found by the visitors, and the ten figurines.[5] (In Chapter 7, Vera Claythorne becomes semi-hysterical at the mention by Miss Brent of "our black brothers", which is understandable only in the context of the original name.) UK editions continued to use the original title until the current definitive title appeared with a reprint of the 1963 Fontana Paperback in 1985.[21]

The word "nigger" was already racially offensive in the United States by the start of the 20th century, and therefore the book's first US edition and first serialization changed the title to And Then There Were None and removed all references to the word from the book, as did the 1945 motion picture (except that the first US edition retained 'nigger in the woodpile' in chapter 2 part VIII). Sensitivity to the original title of the novel was remarked by Sadie Stein in 2016, commenting on a BBC mini series with the title And Then There Were None, where she noted that "[E]ven in 1939, this title was considered too offensive for American publication."[22] In general, "Christie’s work is not known for its racial sensitivity, and by modern standards her oeuvre is rife with casual Orientalism."[22] The original title was based on a rhyme from minstrel shows and children's games. Stein quotes Alison Light as to the power of the original name of the island in the novel, Nigger Island, "to conjure up a thrilling ‘otherness’, a place where revelations about the ‘dark side’ of the English would be appropriate".[23] Light goes on to say that "Christie's location [the island] is both more domesticated and privatised, taking for granted the construction of racial fears woven into psychic life as early as the nursery."[23] Speaking of the "widely known" 1945 film, Stein added that "we’re merely faced with fantastic amounts of violence, and a rhyme so macabre and distressing one doesn’t hear it now outside of the Agatha Christie context."[22] She felt that the original title of the novel in the UK, seen now, "that original title, it jars, viscerally."[22]

Best selling crime novel

This is the best selling crime novel of all time, and what makes Agatha Christie the best selling novelist.[2] It is Christie's best-selling novel, with more than 100 million copies sold; it is also the world's best-selling mystery and one of the best-selling books of all time. Publications International lists the novel as the sixth best-selling title.[7]

Editions in English

The book and its adaptations have been released under various new names since the original publication, including Ten Little Indians (1946 play, Broadway performance and 1964 paperback book), Ten Little Soldiers, and official title per the Agatha Christie Limited website, And Then There Were None.[2] UK editions continued to use the work's original title until the 1980s; the first UK edition to use the alternative title And Then There Were None appeared in 1985 with a reprint of the 1963 Fontana Paperback.[21]

- Christie, Agatha (November 1939). Ten Little Niggers. London: Collins Crime Club. OCLC 152375426. Hardback, 256 pp. First edition.

- Christie, Agatha (January 1940). And Then There Were None. New York: Dodd, Mead. OCLC 1824276. Hardback, 264 pp. First US edition.

- Christie, Agatha (1944). And Then There Were None. New York: Pocket Books (Pocket number 261). Paperback, 173 pp.

- Christie, Agatha (1947). Ten Little Niggers. London: Pan Books (Pan number 4). Paperback, 190 pp.

- Christie, Agatha (1958). Ten Little Niggers. London: Penguin Books (Penguin number 1256). Paperback, 201 pp.

- Christie, Agatha (1963). Ten Little Niggers. London: Fontana. OCLC 12503435. Paperback, 190 pp. The 1985 reprint was the first UK publication of the novel under the title And Then There Were None.[21]

- Christie, Agatha (1964). Ten Little Indians. New York: Pocket Books. OCLC 29462459. First publication of novel as Ten Little Indians.

- Christie, Agatha (1964). And Then There Were None. New York: Washington Square Press. Paperback, teacher's edition.

- Christie, Agatha (1977). Ten Little Niggers (Greenway ed.). London: Collins Crime Club. ISBN 0-00-231835-0. Collected works, Hardback, 252 pp. (Except for reprints of the 1963 Fontana paperback, this was one of the last English-language publications of the novel under the title Ten Little Niggers.)[24]

- Christie, Agatha (1980). The Mysterious Affair at Styles; Ten Little Niggers; Dumb Witness. Sydney: Lansdowne Press. ISBN 0-7018-1453-5. Late use of the original title in an Australian edition.

- Christie, Agatha (1986). Ten Little Indians. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-55222-8. Last publication of novel under the title Ten Little Indians.

Foreign-language editions

The sensitivity of the original British title varies across nations, depending on their culture and which words are used to describe people by skin colour. In the US, the British title was considered offensive at first publication, and changed to the last line of the rhyme instead of its title. As the estate of Agatha Christie now offers it under only one title in English, And Then There Were None,[2] it seems likely that new foreign-language editions will match that title in their language. The original title (Ten Little Niggers) still survives in a few foreign-language versions of the novel, and was used in other languages for a time, for example in Dutch until the 1994 release of the 18th edition. The title Ten Little Negroes continues to be commonly used in foreign-language versions, for example in Spanish, Greek, Serbian, Bulgarian, Romanian,[25] French[26] and Hungarian, as well as a 1987 Russian film adaptation Десять негритят (Desyat Negrityat). In 1999, the Slovak National Theatre staged the play under its original title but changed to A napokon nezostal už nik (And Then There Were None) mid-run.[27]

Possible inspirations

The 1930 novel The Invisible Host by Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning has a plot that strongly matches that of Christie's later novel, including a recorded voice announcing to the guests that their sins will be visited upon them by death. The Invisible Host was adapted as the 1930 Broadway play The Ninth Guest by Owen Davis,[28] which itself was adapted as the 1934 film The Ninth Guest. There is no evidence Christie saw either the play (which had a brief run on Broadway) or the film.

The 1933 K.B.S. Productions Sherlock Holmes film A Study in Scarlet follows a strikingly similar plot;[29] it includes a scene where Holmes is shown a card with the hint: "Six little Indians...bee stung one and then there were five". In this case, the rhyme refers to "Ten Little Fat Boys". (The film's plot bears no resemblance to Arthur Conan Doyle's original story of the same name.) The author of the movie's screenplay, Robert Florey, "doubted that [Christie] had seen A Study in Scarlet, but he regarded it as a compliment if it had helped inspire her".[30]

Adaptations

And Then There Were None has had more adaptations than any other single work by Agatha Christie.[2] Christie herself changed the bleak ending to a more palatable one for theatre audiences when she adapted the novel for the stage in 1943. Many adaptations incorporate changes to the story, such as using Christie's alternative ending from her stage play or changing the setting to locations other than an island.

Film

There have been numerous film adaptations of the novel:

- And Then There Were None (1945 film), by René Clair

- Ten Little Indians (1965 film) by George Pollock

- Gumnaam (1965, translation: Unknown or Anonymous), an Indian suspense thriller[31]

- Nadu Iravil (1970, translation: In the middle of the night), a Tamil adaptation directed by Sundaram Balachander[32]

- And Then There Were None (1974), the first English-language colour version, directed by Peter Collinson

- Desyat' Negrityat (1987, Десять негритят, Eng: "Ten Little Negroes") a Russian adaptation by Stanislav Govorukhin

- Ten Little Indians, a 1989 American version directed by Alan Birkinshaw

- Mindhunters, a 2004 American-British crime thriller

- Aduthathu, a 2012 Tamil adaptation[33]

- Aatagara, a 2015 Kannada adaptation[34]

Radio

- The BBC broadcast Ten Little Niggers (1947), adapted by Ayton Whitaker, first aired as a Monday Matinee on the BBC Home Service on 27 December 1947 and as Saturday Night Theatre on the BBC Light Programme on 29 December.[35]

- On 13 November 2010, as part of its Saturday Play series, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a 90-minute adaptation written by Joy Wilkinson. The production was directed by Mary Peate and featured Geoffrey Whitehead as Justice Wargrave, Lyndsey Marshal as Vera Claythorne, Alex Wyndham as Philip Lombard, John Rowe as Dr. Armstrong, and Joanna Monro as Emily Brent.

Stage

- And Then There Were None (1943 play) is Christie's adaptation of the story for the stage. She and the producers agreed that audiences might not flock to a tale with such a grim ending as the novel, nor would it work well dramatically as there would be no one left to tell the story. Christie reworked the ending for Lombard and Vera to be innocent of the crimes of which they were accused, survive, and fall in love with each other. Some of the names were also changed, e.g., General Macarthur became General McKenzie in both the New York and London productions.[36][37] By 1943, General Douglas MacArthur was playing a prominent role in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, which may explain the change of the character's name.

- Ten little niggers (1944 play), Dundee Repertory Theatre Company was given special permission to restore the original ending of the novel. The company first performed a stage adaptation of the novel in August 1944 under the UK title of the novel, with Christie credited as the dramatist.[38] It was the first performance in repertory theatre.[38] It was staged again in 1965.[39] There was an article in the Dundee Evening Register in August 1944

- And Then There Were None (2005 play). On 14 October 2005, a new version of the play, written by Kevin Elyot and directed by Steven Pimlott, opened at the Gielgud Theatre in London. For this version, Elyot returned to the original story in the novel, restoring the nihilism of the original.[40]

Television

Several variations of the original novel were adapted for television, three of which were British adaptations. The first of these, in 1949, was produced by the BBC.[41] The second was produced in 1959,[42] by ITV. Both of those productions aired with Christie's original title. The third and most recent British adaptation aired as And Then There Were None on BBC One in December 2015, as a mini-series produced in cooperation with Acorn Media and Agatha Christie Productions. The 2015 production adhered more closely to the original plot, though there were several differences, and was the first English language film adaptation to feature an ending similar to that of the novel.[43]

In 2011, Spanish RTVE made a free adaptation of the plot as the two-parter The mystery of the ten strangers for the second season of Los misterios de Laura.

On 25 and 26 March 2017, TV Asahi in Japan aired Soshite daremo inakunatta (そして誰もいなくなった), a Japanese-language adaptation by Shukei Nagasaka (長坂秀佳, Nagasaka Shukei) set in modern times.[44][45]

Other media

The novel was the inspiration for several video games. For the Apple II, Online Systems released Mystery House in 1980. On the PC, The Adventure Company released Agatha Christie: And Then There Were None in 2005, the first in a series of PC games based on Christie novels. In February 2008, it was ported to the Wii console. The game adheres closely to the novel in most respects, and uses some of its dialogue verbatim, but makes significant changes to the plot in order to give the player an active role and allow those familiar with the novel to still experience some suspense. The player assumes the role of Patrick Naracott (brother of Fred Naracott, who is involved in a newly created subplot), who is stranded with the others when his boat is scuttled. The killer's identity and motives are different, the means of three of the murders were changed (while still corresponding to the rhyme), and it is possible for the player to save two of the victims, with the game branching into four different endings depending on which of the two are saved.

And Then There Were None was released by HarperCollins as a graphic novel adaptation on 30 April 2009, adapted by François Rivière and illustrated by Frank Leclercq.

Peká Editorial released a board game based on the book, Diez Negritos ("Ten Little Negroes"), created by Judit Hurtado and Fernando Chavarría, and illustrated by Esperanza Peinado.[46]

The 2014 live action comedy-crime and murder mystery TV web series, Ten Little Roosters produced by American company Rooster Teeth is largely inspired by And Then There Were None.[47] It featured an interactive murder mystery component where viewers guess who will die next, and how, in order to win prizes. The premise of the show is nearly identical to the book, but with a lighter, more comedic tone and the plot is structured so that anyone having read And Then There Were None would be unable to apply their knowledge of the book's plot twists.

Timeline of adaptations

| type | Title | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Film | And Then There Were None | 1945 | American film and first cinema adaptation. Produced & directed by René Clair. |

| TV | Ten Little Niggers | 1949 | BBC television production |

| TV | Ten Little Niggers | 1959 | ITV television production |

| TV | Ten Little Indians | 1959 | NBC television production |

| Film | Ten Little Indians | 1965 | British film and second cinema adaptation. Directed by George Pollock and produced by Harry Alan Towers; Pollock had previously handled four Miss Marple films starring Margaret Rutherford. Set in a mountain retreat in Austria. |

| Film | Gumnaam | 1965 | Loose, uncredited Hindi film adaptation, which adds the characteristic "Bollywood" elements of comedy, music and dance to Christie's plot.[31] |

| TV | Zehn kleine Negerlein | 1969 | West German television production |

| Film | And Then There Were None | 1974 | English language film by Peter Collinson and produced by Harry Alan Towers. First English-language colour film version of the novel, based on a screenplay by Towers (writing as "Peter Welbeck"), who co-wrote the screenplay for the 1965 film. Set at a grand hotel in the Iranian desert. |

| TV | Ten Little Slaves (Achra Abid Zghar) | 1974 | Télé Liban TV series directed by Jean Fayyad, TV Adaptation by Latifeh Moultaka. |

| Film | Desyat' negrityat Десять негритят ("Ten Little Negroes") | 1987 | Russian film version produced/directed by Stanislav Govorukhin, notable for being the first cinema adaptation to keep the novel's original plot and grim ending. |

| Film | Ten Little Indians | 1989 | British film, produced by Harry Alan Towers and directed by Alan Birkinshaw, set on safari in the African savannah. |

| TV | Ten Little Slaves (Achra Abid Zghar) | 2014 | MTV Lebanon television production |

| TV | And Then There Were None | 2015 | BBC One miniseries broadcast on three consecutive nights, directed by Craig Viveiros and adapted by Sarah Phelps. Similar to book, although not identical, with changes to backstories and actual murders on the island. |

| TV | Soshite Daremo Inakunatta | 2017 | Japanese TV Asahi miniseries broadcast on two consecutive nights, directed by Seiji Izumi and adapted by Hideka Nagasaka. |

References

- "British Library Item details". primocat.bl.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "And Then There Were None". Agatha Christie Limited. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Review of Ten Little Niggers". The Observer. 5 November 1939. p. 6.

- Peers, Chris; Spurrier, Ralph; Sturgeon, Jamie (1999). Collins Crime Club: a checklist of the first editions (2nd ed.). London, UK: Dragonby Press. p. 15. ISBN 1-871122-13-9.

- Pendergast, Bruce (2004). Everyman's Guide to the Mysteries of Agatha Christie. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing. p. 393. ISBN 1-4120-2304-1.

- "American Tribute to Agatha Christie: The Classic Years 1940–1944". J S Marcum. May 2004. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Davies, Helen; Dorfman, Marjorie; Fons, Mary; Hawkins, Deborah; Hintz, Martin; Lundgren, Linnea; Priess, David; Clark Robinson, Julia; Seaburn, Paul; Stevens, Heidi; Theunissen, Steve (14 September 2007). "21 Best-Selling Books of All Time". Editors of Publications International, Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- Christie, Agatha (1964). Ten Little Niggers. London: The Crime Club. pp. 31–32. Original nursery rhyme.

- Ashley, Maurice Percy Ashley (11 November 1939). "Review: Ten Little Indians". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 658.

- Anderson, Isaac (25 February 1940). "Review: Ten Little Indians". The New York Times Book Review. p. 15.

- "Review: Ten Little Indians". Toronto Daily Star. 16 March 1940. p. 28.

- Barnard, Robert (1990). A Talent to Deceive – an appreciation of Agatha Christie (Revised ed.). Fontana Books. p. 206. ISBN 0-00-637474-3.

- Light, Alison (1991). Forever England: Femininity, Literature, and Conservatism Between the Wars. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 0-415-01661-4.

- "Binge! Agatha Christie: Nine Great Christie Novels". Entertainment Weekly (1343–44): 32–33. 26 December 2014.

- Christie, Agatha (1944). And Then There Were None: A Mystery Play in Three Acts. Samuel French.

This line is sometimes replaced by One got left behind and then there were seven.

- Note: In some versions the ninth verse reads Two little Soldier boys playing with a gun/One shot the other and then there was One.

- Christie, Agatha (March 2008). And Then There Were None. Harper-Collins. p. 276. ASIN B000FC1RCI. ISBN 978-0-06-074683-4.

- Ten Little Niggers, song written in 1869 by Frank Green, for music by Mark Mason, for the singer G W "Pony" Moore. Agatha Christie, for the purposes of her novel, changed the story of the last little boy "One little nigger boy left all alone / He went out and hanged himself and then there were none".

- Ten Little Indians, song by Septimus Winner, American lyricist residing in Philadelphia, published in July 1868 in London.

- Holdings at the British Library (Newspapers – Colindale); Shelfmark NPL LON LD3/NPL LON MLD3.

- "British National Bibliography for 1985". British Library. 1986. ISBN 0-7123-1035-5. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Stein, Sadie (5 February 2016). "Mystery". The Paris Review. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Light, Alison (2013) [1991]. Forever England: Femininity, Literature and Conservatism Between the Wars. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-135-62984-7.

- Whitaker's Cumulative Book List for 1977. J Whitaker and Sons. 1978. ISBN 0-85021-105-0.

- ""Zece negri mititei" si "Crima din Orient Express", azi cu "Adevarul"" (in Romanian). Adevarul.ro. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- "Dix petits nègres, nouvelle édition: Livres: Agatha Christie" (in French). Amazon.fr. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- "Agatha Christie: Desať malých černoškov ... a napokon nezostal už nik". Snd.sk. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- Davis, Owen (1930). The Ninth Guest: A Mystery Melodrama In Three Acts. New York City: Samuel French & Co.

- Taves, Brian (1987). Robert Florey, the French Expressionist. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 152. ISBN 0-8108-1929-5.

- Taves, Brian (1987). Robert Florey, the French Expressionist. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-8108-1929-5.

- "Aboard the mystery train". Cinema Express. 22 November 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

Gumnaam (1965) Adapted from: And Then There Were None

- "Author of incredible reach". The Hindu. 24 October 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Agatha Christie e il cinema: un amore mai sbocciato del tutto" (in Italian). Comingsoon.it. 12 January 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Aatagara is not a remake". Bangalore Mirror. 30 August 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Ten Little Niggers". Radio Times (1263). 26 December 1947.

- "Ten Little Indians at Two New York City playhouses 1944-1945". The Broadway League, including cast and characters. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Christie, Agatha (1993). The Mousetrap and Other Plays. HarperCollins. p. 2. ISBN 0-00-224344-X.

- "Ten little niggers, stage production at Dundee Repertory Theatre". Dundee, Scotland: Scottish Theatre Archive - Event Details. August 1944. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Ten little niggers staged at Dundee Repertory Theatre 1944 and 1965". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "And Then There Were None". Review. This Is Theatre. 14 October 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- BBC TV (20 August 1949). "Ten Little Niggers". Radio Times (1348). p. 39.

- "Season 4, Episode 20 'Ten Little Niggers'". Play of the Week. ITV. 13 January 1959.

- "And Then There Were None to air on BBC1 on Boxing Day 2015". Radio Times. 2 December 2015.

- "And Then There Were None in Japan". Agatha Christie. Agatha Christie Limited. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "そして誰もいなくなった" [And Then There Were None]. TV Asahi (in Japanese). TV Ashi. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Peká Editorial website". Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Staff, Wrap PRO (5 November 2014). "Rooster Teeth Premieres Interactive Murder Mystery Web Series". WrapPRO. Retrieved 13 May 2019.