Abortifacient

An abortifacient ("that which will cause a miscarriage" from Latin: abortus "miscarriage" and faciens "making") is a substance that induces abortion. This is a nonspecific term which may refer to any number of substances or medications, ranging from herbs[1] to prescription medications.[2]

Common abortifacients used in performing medical abortions include mifepristone, which is typically used in conjunction with misoprostol in a two-step approach.[3] Synthetic oxytocin, which is routinely used safely during term labor, is also commonly used to induce abortion in the second or third trimester.[4] Historically, a variety of herbs have been used globally to induce abortion,[5] although many of these have not been studied and may have unintended and lethal side effects.[6]

Medications

Because "abortifacient" is a broad term used to describe a substance's effects on pregnancy, there is a wide range of drugs that can be described as abortifacients or as having abortifacient properties.

The most commonly recommended medication regimen for intentionally inducing abortion involves the use of mifepristone followed by misoprostol 1-2 days later.[7] The use of these medications for the purpose of ending a pregnancy has been extensively studied, and has been shown to be both effective and safe[8] with fewer than 0.4% of patients needing hospitalization to treat an infection or to receive a blood transfusion. This combination is approved for use up to 10 weeks' gestation (70 days after the start of the last menstrual period).[9]

Other drugs with abortifacient properties can have multiple uses. Both synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin) and dinoprostone (Cervidil, Prepidil) are routinely used during healthy, term labor. Pitocin is used to induce and strengthen contractions[10], and Cervidil is used to prepare the cervix for labor by inducing softening and widening of this opening to the uterus[11]. When used this way, neither medication is considered an abortifacient. However, the same drugs can be used to induce an abortion, particularly after 12 weeks of pregnancy[12][13]. Misoprostol (discussed above) is also used to treat peptic ulcers[14] in patients who have suffered gastric or intestinal damage from use of NSAIDs. Because its use in treatment of ulcers makes it easier to access, misoprostol alone is sometimes used for self-induced abortion in countries or regions where legal abortion is not available or readily accessible.[15]

Not all abortifacient agents are taken with the intention to end a pregnancy. Methotrexate, a drug often used for management of rheumatoid arthritis, can induce abortion. For this reason contraception is often advised while using methotrexate for management of a chronic condition.[16]

History

In the Bible, many commentators view the ordeal of the bitter water (prescribed for a sotah, or a wife whose husband suspects that she was unfaithful to him) as intended to cause the abortion of a potential bastard. The wife drinks "water of bitterness," which, if she is guilty, causes the abortion or miscarriage of a pregnancy she may be carrying.[17][18][19][20][21][22][23] Others dispute this interpretation,[24] saying that "There is no reason to suppose that the woman was pregnant at the time"[24]:18 and "Final proof of the woman's innocence would be pregnancy, final proof of her guilt would be the 'belly swelling and thigh falling' which possibly describes the prolapsed uterus."[24]:24

The ancient Greek colony of Cyrene at one time had an economy based almost entirely on the production and export of the plant silphium, considered a powerful abortifacient.[25] Silphium figured so prominently in the wealth of Cyrene that the plant appeared on coins minted there. Silphium, which was native only to that part of Libya, was overharvested by the Greeks and was effectively driven to extinction.[25] The standard theory, however, has been challenged by a whole spectrum of alternatives (from an extinction due to climate factors, to the so-coveted product being in fact a recipe made of a composite of herbs, attribution to a single species meant perhaps as a disinformation attempt).

In aboriginal Australia, plants such as cymbidium madidum, petalostigma pubescens, or Eucalyptus gamophylla were ingested, inserted into the body, or were smoked with Erythropleum chlorostachyum.[26]

As Christianity and in particular the institution of the Catholic Church increasingly influenced European society, those who dispensed abortifacient herbs found themselves classified as witches and were often persecuted in witch-hunts.[27]

Medieval Muslim physicians documented detailed and extensive lists of birth control practices, including the use of abortifacients, commenting on their effectiveness and prevalence. The use of abortifacients was acceptable to some Islamic jurists provided that the abortion occurs within 120 days of conception, the time when the fetus is believed to receive its soul, though others considered the procedure fully prohibited.[28]

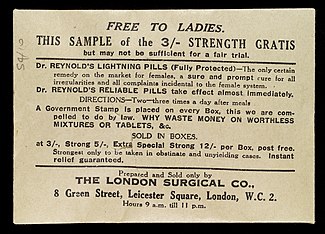

In English law, abortion did not become illegal until 1803. English folk practice before and after that time held that fetal life was not present until quickening. "Women who took drugs before that time would describe their actions as 'restoring the menses' or 'bringing on a period'."[29] Abortifacients used by women in England in the 19th century (not necessarily safe or effective) included diachylon, savin, ergot of rye, pennyroyal, nutmeg, rue, squills, and hiera picra,[30] the latter being a mixture of powdered aloe and canella.[31]

During the American slavery period, 18th and 19th centuries, cotton root bark was used in folk remedies to induce a miscarriage.[32]

See also

- Georg Eberhard Rumphius – documented some claims of abortifacient properties of herbs[33]

Dangers of abortifacient herbs

The use of herbs as abortifacients can cause serious – even lethal – side effects.[34] Such use is dangerous and is not recommended by physicians.[35]

References

- Kumar, Dinesh; Kumar, Ajay; Prakash, Om (6 March 2012). "Potential antifertility agents from plants: A comprehensive review". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 140 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.039. ISSN 0378-8741.

- "Medical abortion - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "Medical abortion - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Borgatta, Lynn; Kapp, Nathalie (July 2011). "Labor induction abortion in the second trimester". Contraception. 84 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.005.

- Riddle, John M. (1992). Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press ISBN 0-674-16876-3.

- Ciganda, Carmen; Laborde, Amalia (2003). "Herbal infusions used for induced abortion". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 41 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1081/clt-120021104. ISSN 0731-3810. PMID 12807304.

- "Medical management of abortion". www.who.int. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Raymond, Elizabeth G.; Shannon, Caitlin; Weaver, Mark A.; Winikoff, Beverly (1 January 2013). "First-trimester medical abortion with mifepristone 200 mg and misoprostol: a systematic review". Contraception. 87 (1): 26–37. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.011. ISSN 0010-7824.

- Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (12 April 2019). "Questions and Answers on Mifeprex". FDA.

- "Pitocin - FDA.gov" (PDF). FDA - Drug Safety and Availability.

- PubChem. "Dinoprostone". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Dinoprostone (Vaginal Route) Proper Use - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Borgatta, Lynn; Kapp, Nathalie (July 2011). "Labor induction abortion in the second trimester". Contraception. 84 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.005.

- "Misoprostol: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- John Leland: "Abortion Might Outgrow Its Need for Roe v. Wade", The New York Times, 2 October 2005

- Reinholz, Lou (2011). "Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine Sixth Edition". Pediatric Emergency Care. 27 (2): 89. doi:10.1097/pec.0b013e31820a9a4f. ISSN 0749-5161.

- Gordon, R.P. (2007). The God of Israel. Cambridge University Press. p. 128.

- Berquist, Jon L. (2002). Controlling Corporeality: The Body and the Household in Ancient Israel. Rutgers University Press. pp. 175–177. ISBN 0813530164.

- Levine, Baruch A. (1993). Numbers 1-20: a new translation with introduction and commentary. 4. Doubleday. pp. 201–204. ISBN 0385156510.

- Snaith, Norman Henry (1967). Leviticus and Numbers. Nelson. p. 202.

- Olson, Dennis T. (1996). Numbers: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 36. ISBN 0664237363.

- Brewer, Julius A. (October 1913). "The Ordeal in Numbers Chapter 5". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 30 (1): 46.

- Biale, Rachel (1995). Women and Jewish Law: The Essential Texts, Their History, and Their Relevance for Today. Random House Digital. p. 186. ISBN 0805210490.

- Frymer-Kensky, Tikva (1 January 1984). "The Strange Case of the Suspected Sotah (Numbers V 11-31)". Vetus Testamentum. 34 (1): 11–26. doi:10.1163/156853384X00025. ISSN 1568-5330.

- Rossetti, Chip (July–August 2009). "Devil's Dung - The World's Smelliest Spice". Saudi Aramco World. Vol. 60 no. 4. pp. 36–43. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013.

- Isaacs, Jennifer (1987). Bush Food: Aboriginal Food and Herbal Medicine. Weldons. ISBN 978-0-949708-33-5.

- Kramer, Heinrich, & Sprenger, Jacob. (1487). Malleus Maleficarum. (Montague Summers, Trans.). Retrieved 3 June 2006.

- Sheikh, Sa'diyya (2003). "Family Planning, Contraception, and Abortion in Islam". In Maguire, Daniel C. (ed.). Sacred Rights: The Case for Contraception and Abortion in World Religions. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-516001-0.

- McLaren, Angus (1978). Birth Control in Nineteenth-Century England. Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. US. pp. 31, 246. ISBN 0-8419-0349-2.

- "The Annus Medicus 1899". The Lancet. 154 (3983): 1819–49 [1844–5]. 1899. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)40125-5., cited by McLaren, p. 241

- Dunglison, Robley (1874). A Dictionary of Medical Science. Henry C. Lea. p. 501.

- Perrin, Liese M. (2001). "Resisting Reproduction: Reconsidering Slave Contraception in the Old South". Journal of American Studies. 35 (2): 255–274. doi:10.1017/S0021875801006612. JSTOR 27556967.

- "environment: YALE magazine - Fall 2010". environment.yale.edu.

- Ciganda, C.; Laborde, A. (2003). "Herbal infusions used for induced abortion". Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology. 41 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1081/CLT-120021104. PMID 12807304.

- Kutner, Jenny (6 January 2016). "Women Are Learning about Herbal Abortion Online -- Here's Why That's a Problem".

External links