383 Madison Avenue

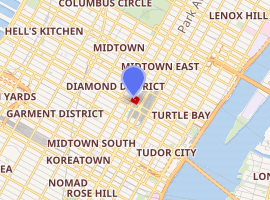

383 Madison Avenue is an office building owned and occupied by JP Morgan Chase in New York City on a full block bound by Madison Avenue and Vanderbilt Avenue between East 46th and 47th Streets. Formerly known as the Bear Stearns Building, it housed the world headquarters of the now-defunct Bear Stearns from the building's completion until Bear's collapse and sale to JPMorgan Chase in 2008. The building now houses the New York offices for J.P. Morgan's investment banking division, which formerly occupied 277 Park Avenue. Both 383 Madison and 277 Park are adjacent to JPMorgan Chase's world headquarters address, 270 Park Avenue, and the 383 Madison building is serving as temporary headquarters while 270 Park is being redeveloped.

| 383 Madison Avenue | |

|---|---|

383 Madison Avenue at night | |

| |

| Alternative names |

|

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Commercial/Office |

| Location | 383 Madison Avenue, New York City, New York |

| Construction started | 1999 |

| Completed | 2001 |

| Opening | 2002 |

| Owner | JP Morgan Chase |

| Height | |

| Roof | 230 m (755 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 47 |

| Floor area | 1,200,000 sq ft (110,000 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | David Childs (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill) |

| Structural engineer | LeMessurier Consultants WSP Cantor Seinuk |

| Main contractor | Turner Construction Company |

A night time photograph of the building taken at a steep angle from its base appears on the cover of William D. Cohan's book, House of Cards: A Tale of Hubris and Wretched Excess on Wall Street (2009).

History

The original building at 383 Madison was a 14-story, 505,000 square feet (46,900 m2) limestone office building designed by Cross & Cross named the Knapp Building.[1] The building occupied the entire block and had served as the headquarters of the Manhattan Savings Bank, BBDO[2] and William Zeckendorf's Webb & Knapp.[3]

In October 1982, G Ware Travelstead and First Boston acquired the building for $77.75 million and hired Skidmore, Owings & Merrill to design a new replacement for the site.[4] Initial studies for the project reached up to 2,200,000 square feet (200,000 m2) and 140 stories, taller than Sears Tower, the tallest building in the world at the time.[1]

A 72-story, 1,040 feet (320 m) tall tower was later proposed in the mid 1980s.[5] The building (also referred to as Travelstead Tower[6]), which would have been the fourth-tallest in New York City, was designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox and would have spanned 1,400,000 square feet (130,000 m2). However, the site was only zoned for 600,000 square feet (56,000 m2) and needed to purchase additional air rights from Grand Central Station to hit the targeted square footage.[7]

The building ran into opposition trying to transfer the air rights, with New York's Manhattan Community Board 5 voting unanimously to deny the transfer in June 1989.[5] Following the Community Board's opposition, the New York City Planning Commission also unanimously disapproved of the transfer.[8] The developers sued the city in New York Supreme Court, but the court upheld the city's decision to deny the rights transfer, effectively cancelling the project.[9]

In 1994, Howard Ronson's HRO International signed a deal giving the firm the option to buy the property for $55 million from First Boston.[10] The developer planned a 24-story, $200 million building named Park Avenue Place on the site.[11] The 800,000 square feet (74,000 m2) tower was planned for completion in the third quarter of 1996. HRO planned to reuse the old building's foundations and also solicited tax breaks from the city government.[11] Ronson was reportedly in discussions with Morgan Guaranty Trust and Swiss Re about anchoring the building.[12]

However, in January 1996 First Boston reneged on their deal with HRO and instead signed a contract to sell the land to Bear Stearns.[10] Another conflict unfolded when First Boston's partner in the site, the al-Babtain family of Saudi Arabia, announced in February 1996 that they would be buying out First Boston's stake to take control of the entire site.[13] The family's ownership stake included a right of first refusal if First Boston attempted to sell the property.

JP Morgan Chase entered negotiations with the al-Babtain family in October 1996, hoping to build a new headquarters for themselves on the site, near their existing headquarters at 270 Park Avenue.[12]

Bear Stearns signed a 99-year lease for the land beneath the building in 1999 with plans to move its headquarters and most of its 4,500 employees to the new building.[3]

The building changed hands in 2008 during JP Morgan's takeover of Bear Stearns. On their second-quarter 2008 conference call, JP Morgan estimated the building's value at $1.1 to $1.4 billion.

Architecture and design

Designed by David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP, it is 755 ft (230 m) tall with 47 floors. Hines Interests managed the development process for Bear Stearns. It was completed in 2001 and opened in 2002, at which time it was, by some reports, the 88th tallest building in the world. The building has approximately 110,000 rentable square meters (1,200,000 sq ft).

The building has an octagonal tower that rises out of a rectangular base to a 20 m (70 ft) crown made of glass which is illuminated at night. Two-thirds of the building’s foundation sit on slabs atop Metro-North tracks rather than being attached to the bedrock itself. The tunnels also required Bear Stearns to move HVAC and mechanical equipment that would usually sit in the basement up higher in the building.[14]

The building was designed to be able to run for four days without exterior power through four 7,500 KW emergency electrical generators, its own steam turbines, and tanks that could store 109,000 gallons of emergency water. When it opened, the building contained 23 high-speed elevators capable of traveling 14,000 feet per minute.[14] Floors 3 through 11 served as Bear Stearn's trading floors. Each floor was 44,000 square feet (4,100 m2) and each housed 285 traders.[14]

The building's visually decorative design differs from the conventional functionalist style of neighboring office buildings, and hence has proven unpopular with some critics. New York said, "This is a building you wouldn't want to get anywhere near at a cocktail party. Dressed nearly head to toe in dour granite, and geometrically proper, it's stiff to the point of pass-out boredom. Out of character with SOM's (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill's) current work, the design recalls the firm's unfortunate postmodern interlude a decade ago."[15]

- Note the glass "crown" at top

See also

- List of tallest buildings in New York City

- List of tallest buildings in the United States

Notes

- Horsley, Carter (November 26, 1983). "AIR RIGHTS BOUGHT AT GRAND CENTRAL". New York Times.

- Dougherty, Philip (July 6, 1987). "Advertising; BBDO Leaves Madison Ave". New York Times.

- McDowell, Edwin (February 13, 2000). "Around Grand Central, New Office Towers And a 54-Floor Residence". New York Times.

- Oser, Alan (June 19, 1983). "MANHATTAN DRAWING THE BRITISH INVESTOR". New York Times.

- Dunlap, David (July 6, 1989). "A Battle Looms Over Grand Central's Air Space". New York Times.

- http://skyscraperpage.com/cities/?buildingID=8332

- "383 Madison Is the Wrong Address". New York Times. September 22, 1986.

- Dunlap, David (August 24, 1989). "Panel Rejects Plan to Shift Grand Central's Air Rights". New York Times.

- Dunlap, David (August 8, 1991). "Plan to Use Grand Central Air Rights for Tower Is Rejected". New York Times.

- Pulley, Brett (January 25, 1996). "Bear, Stearns Signs Deal For Valuable Midtown Site". New York Times.

- Deutsch, Claudia (April 17, 1994). "Commercial Property/383 Madison Avenue; New Office Tower For Midtown?". New York Times.

- Feldman, Amy (October 14, 1996). "CHASE WEIGHING HQ AT EMBATTLED MADISON ADDRESS : PLANS MAY INCLUDE ERECTING WORLD'S TALLEST BUILDING AT FOUGHT-OVER TURF : CHASE CONSIDERS HQ AT MADISON ADDRESS". Crain's New York.

- Deutsch, Claudia (February 17, 1996). "New Bid May Undo Deal for Manhattan Site". New York Times.

- Verini, James (July 23, 2001). "Battleship B.S.: With Its New $516-Million Tower, Bear Stearns Bunkers Down for the Big One". New York Observer.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 12, 2005. Retrieved November 12, 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

- Building ID 100372—Emporis.com

- 3D Model of the building in Google 3D Warehouse