1975 United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum

The United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum, also known variously as the Referendum on the European Community (Common Market), the Common Market referendum and EEC membership referendum, took place under the provisions of the Referendum Act 1975 on 5 June 1975 in the United Kingdom to gauge support for the country's continued membership of the European Communities (EC) — often known at the time as the European Community and the Common Market — which it had entered two-and-a-half years earlier on 1 January 1973 under the Conservative government of Edward Heath. The Labour Party's manifesto for the October 1974 general election had promised that the people would decide through the ballot box whether to remain in the EC.[1]

| United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | United Kingdom (pop. 56.225m) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | 5 June 1975 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome | The UK votes to remain in the European Communities (Common Market) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Referendum held on 5 June 1975. The electorate of 40.087m represented 71.3% of the population of 56.225m) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

This was the first national referendum ever to be held throughout the United Kingdom, and would remain the only UK-wide referendum until the 2011 referendum on the Alternative Vote system was held thirty-six years later. It was also the only referendum to be held on the UK's relationship with Europe until the 2016 referendum on continued EU membership, which began the process of the UK leaving the EU pursuant to Article 50 (Brexit).

The electorate expressed significant support for EC membership, with 67% in favour on a national turnout of 64%. The referendum result was not legally binding; however, it was widely accepted that the vote would be politically binding on all future Westminster Parliaments. In a 1975 pamphlet Prime Minister Harold Wilson said: "I ask you to use your vote. For it is your vote that will now decide. The Government will accept your verdict."[2] The pamphlet also said: "Now the time has come for you to decide. The Government will accept your decision — whichever way it goes."

The February 1974 general election had yielded a Labour minority government, which then won a majority in the October 1974 general election. Labour pledged in its February 1974 manifesto to renegotiate the terms of British accession to the EC, and then to consult the public on whether Britain should remain in the EC on the new terms, if they were acceptable to the government. The Labour Party had historically feared the consequences of EC membership, such as the large differentials between the high price of food under the Common Agricultural Policy and the low prices prevalent in Commonwealth markets, as well as the loss of both economic sovereignty and the freedom of governments to engage in socialist industrial policies, and party leaders stated their opinion that the Conservatives had negotiated unfavourable terms for Britain.[3] The EC heads of government agreed to a deal in Dublin on 11 March 1975; Wilson declared: "I believe that our renegotiation objectives have been substantially though not completely achieved", and said that the government would recommend a vote in favour of continued membership.[4] On 9 April, the House of Commons voted by 396 to 170 to continue within the Common Market on the new terms. Along with these developments, the government drafted a Referendum Bill, to be moved in case of a successful renegotiation.

The referendum debate and campaign was an unusual time in British politics and was the third national vote to be held in seventeen months. During the campaign, the Labour Cabinet was split and its members campaigned on each side of the question, an unprecedented breach of Cabinet collective responsibility. Most votes in the House of Commons in preparation for the referendum were only carried after opposition support, and the Government faced several defeats on technical issues such as the handling and format of the referendum counts.

The referendum did temporarily achieve Harold Wilson's ambition to bring the divided Labour Party together on the European issue. (However, eight years later, Labour's 1983 general election manifesto pledged withdrawal from the Communities.)[5] and it significantly strengthened the position of pro-marketeer politicians within Parliament; however, despite the large and clear majority in favour of remaining when the vote took place, it ultimately failed to achieve the wider objective of permanently settling among the British people the issue of Britain's relationship with the European Communities.

| Part of a series of articles on | ||||||||||

| British membership of the European Union | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

|

Treaty amendments

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Officials and bodies |

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| National and regional referendums held within the United Kingdom and its constituent countries | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the European Union |

|

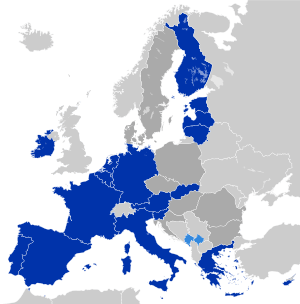

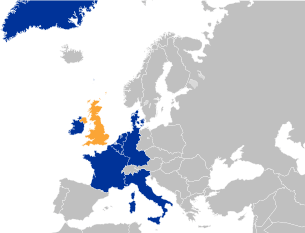

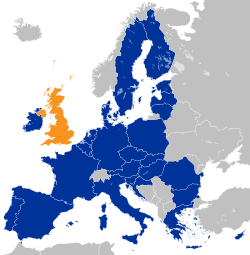

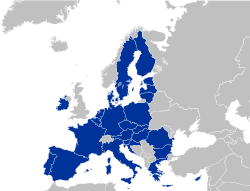

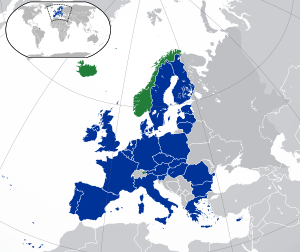

Member States (27) Candidate countries for EU Accession

European Union since 31 January 2020 |

Treaties of Accession

Treaties of Succession

Other Treaties

Abandoned treaties and agreements

|

|

|

Schengen Area Member States

Schengen Area since 2015 |

|

EEA Members

European Economic Area |

|

Former European Bodies

|

Elections in EU Member States

|

|

Policies and Issues |

|

Other

Non-Schengen Area States

|

|

Foreign relations of EU Member States

|

|

|

When the European Coal and Steel Community was instituted in 1952, the United Kingdom decided not to become a member. The UK was still absent when the Treaty of Rome was signed in 1957, creating the European Economic Community (the "Common Market"). However, in the late 1950s the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan dramatically changed its attitude, and appointed Edward Heath to submit an application and to lead negotiations for Britain to enter the Common Market. The application was made at a meeting of the European Communities (EC) in January 1963, but the French president Charles de Gaulle rebuffed and vetoed Britain's request. Despite the veto, Britain restarted talks with the EC countries in 1967; and in April 1970, shortly before the 1970 general election campaign, Heath — who by this time was the Conservative Party leader — said that further European integration would not happen "except with the full-hearted consent of the Parliaments and peoples of the new member countries".[6]

1970 Conservative manifesto commitment and negotiations

The 1970 general election saw all the major political parties commit to either membership or to negotiate with the European Communities. The Conservative manifesto for the election on the issue was committed to negotiating membership but not at any price.[7]

If we can negotiate the right terms, we believe that it would be in the long-term interest of the British people for Britain to join the European Economic Community, and that it would make a major contribution to both the prosperity and the security of our country. The opportunities are immense. Economic growth and a higher standard of living would result from having a larger market.

But we must also recognise the obstacles. There would be short-term disadvantages in Britain going into the European Economic Community which must be weighed against the long-term benefits. Obviously there is a price we would not be prepared to pay. Only when we negotiate will it be possible to determine whether the balance is a fair one, and in the interests of Britain.

Our sole commitment is to negotiate; no more, no less. As the negotiations proceed we will report regularly through Parliament to the country.

A Conservative Government would not be prepared to recommend to Parliament, nor would Members of Parliament approve, a settlement which was unequal or unfair. In making this judgement, Ministers and Members will listen to the views of their constituents and have in mind, as is natural and legitimate, primarily the effect of entry upon the standard of living of the individual citizens whom they represent.

The Conservatives won a total of 330 seats (out of a total of 630) on 46.6% of the national vote share, gaining 77 seats, which gave them an unexpected overall majority of about 30 seats. Edward Heath became Prime Minister, and personally led many of the negotiations which began following the election; he struck up a friendship with the new French president Georges Pompidou, who oversaw the lifting of the veto and thus paved the way for UK membership.

Negotiations on joining the EC first began on 30 June 1970 (coincidentally the same day that the Common Fisheries Policy first came into being) and in the following year a UK Government white paper was published under the title of “The United Kingdom and the European Communities”[8] and Edward Heath called for a parliamentary motion on the white paper. In a ministerial broadcast that was transmitted to the nation ahead of the debate in Parliament he said the following words:

In the autumn Parliament will be asked to decide whether to join the European Community (the Common Market). It's a big decision and it’s one that goes far beyond party politics. It's a decision that will affect us fundamentally whether we go in or stay out. Let's be very clear about it, this is a moment of decision that will not occur again for a very long time if ever.

The debate itself took place between 21 and 28 October 1971, with the House of Commons debating directly whether or not the United Kingdom should become a member of the EC. Conservative MPs were given a free vote, Labour MPs were given a three-line whip to vote against the motion, and Liberal MPs were whipped into voting in favour of the motion. Prime Minister Edward Heath commented in the chamber just before the vote:

But tonight when this House endorses this Motion many millions of people right across the world will rejoice that we have taken our rightful place in a truly United Europe!

The House of Commons voted 356–244 in favour of the motion, a substantial majority of 112, with the Prime Minister commenting straight afterwards on behalf of the House.

Resolved, That this House approves Her Majesty's Government's decision of principle to join the European Communities on the basis of the arrangements which have been negotiated.

No referendum was held when Britain agreed to an accession treaty on 22 January 1972, or when the European Communities Bill went through the legislative process, on the grounds that to hold one would be unconstitutional; the bill passed its second reading in the House of Commons by just eight votes. The United Kingdom joined the European Communities on 1 January 1973, along with Denmark and the Republic of Ireland. The EC would later become the European Union.

Throughout this period, the Labour Party was divided, both on the substantive issue of EC accession and on the question of whether accession ought to be approved by referendum. In 1971 pro-Market figures such as Roy Jenkins, the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, said a Labour government would have agreed to the terms of accession secured by the Conservatives.[3] However, the National Executive Committee and the Labour Party Conference disapproved of the terms. In April 1972, the anti-EC Conservative MP Neil Marten tabled an amendment to the European Communities Bill, which called for a consultative referendum on entry. Labour had previously opposed a referendum, but the Shadow Cabinet decided to support Marten's amendment. Jenkins resigned as Deputy Leader in opposition to the decision, and many Labour MPs abstained in the division.

1974 Labour manifesto commitments

.jpg)

At the February 1974 United Kingdom general election, the Labour Party manifesto promised renegotiation of the UK's terms of membership, to be followed by a consultative referendum on continued membership under the new terms if they were acceptable.

Within one month of coming into office the Labour Government started the negotiations promised in its February manifesto on the basis set out in that manifesto.

It is as yet too early to judge the likely results of the tough negotiations which are taking place. But whatever the outcome in Brussels, the decision will be taken here by the British people.[1]

This could be interpreted as including the option of an election in 1975.[3]

Labour managed to win a very small working majority, and had no need of another general election and the referendum was organised.[9]

Legislation

The government produced a white paper on the proposed referendum on 26 February 1975: it recommended core public funding for both the 'Yes' and 'No' sides, voting rights for members of the armed forces and members of the House of Lords, and finally a proposed single central count of the votes for the whole country. This white paper was approved by the House of Commons. A Referendum Bill was introduced to the Commons on 26 March; at its second reading on 10 April, MPs voted 312–248 in favour. Prior to the Bill's passing, there was no procedure or legislation within the United Kingdom for holding any such plebiscite. The vote, the only nationwide plebiscite to be held in the UK during the 20th century, was of constitutional significance. Referendums had been widely opposed in the past, on the grounds that they violated the principle of parliamentary sovereignty. The first major referendum (i.e. one covering more than one local government area) to be held in any part of the UK had been the sovereignty referendum in Northern Ireland in 1973.[10]

How the votes were to be counted caused much division as the Bill went through Parliament. The government was of the opinion that, given that the poll was substantially different from a general election, and that as a national referendum the United Kingdom was a single constituency, an unprecedented single national count of all the votes for the whole country should take place at Earls Court in London over several days, with one declaration of the final result by the National Counting Officer (later in the legislation the title was changed to Chief Counting Officer). This proposal did not attract the wider support of the Labour Party or the other opposition parties; the Liberal Party favoured individual counts in each of the parliamentary constituencies, and tabled an amendment to this effect, but was defeated by 263 to 131 votes in the House of Commons. However, another amendment, tabled in the Commons by Labour MP Roderick MacFarquhar, sought to have separate counts for each administrative region (the post-1974 county council areas): this won cross-party support, and was carried by 272 to 155 votes.[3]

The Act did not specify any national supermajority of 'Yes' votes for approval of the terms; a simple majority of 50% + 1 vote would suffice to win the vote. It received royal assent on 8 May 1975, just under a month before the vote took place.[11]

Referendum question

The question that would be put to the British electorate, as set out in the Act was:

The Government has announced the results of the renegotiation of the United Kingdom's terms of membership of the European Community. Do you think that the United Kingdom should stay in the European Community (the Common Market)?

A simple YES / NO answer was permitted (to be marked with a single 'X').

The question that was used was one of the options in the Government White Paper of February 1975, although during the passage of the Referendum Bill through Parliament, the Government agreed to add the words "Common Market" in brackets at the end of the question.

The referendum took place 25 years before the passing of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 by the Labour government of Tony Blair, which introduced into British law a general procedure for the holding of all future UK-wide referendums, and also created the Electoral Commission, a body that would oversee such votes and also test and research proposed referendum questions.

Campaigning

The referendum was called in April 1975 after the renegotiation was formally concluded. Since Prime Minister Harold Wilson's cabinet was split between supporters and opponents of the Common Market, and since members of each side held their views strongly, he made the decision, unprecedented outside coalition government, to suspend the constitutional convention of Cabinet collective responsibility. Cabinet members would be allowed to publicly campaign against each other. In total, seven of the twenty-three members of the cabinet opposed EC membership.[12] Wilson's solution was that ministers speaking in the House of Commons should reflect government policy (i.e. support for EC membership), but would be allowed to speak freely elsewhere, thus avoiding a mass dismissal of Cabinet ministers. In spite of this, one minister, Eric Heffer, was obliged to resign after speaking against EC membership in the House of Commons.

Yes campaign (Britain In Europe)

The 'Yes' campaign was officially supported by Wilson[13] and the majority of his cabinet, including the holders of the three other Great Offices of State: Denis Healey, the Chancellor of the Exchequer; James Callaghan, the Foreign Secretary; and Roy Jenkins, the Home Secretary. It was also supported by the majority of the Conservative Party, including its newly elected leader Margaret Thatcher — 249 of 275 party members in Parliament supported staying in the EC in a free vote in April 1975[13] — the Liberal Party, the Social Democratic and Labour Party, the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland and the Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party.

No campaign (National Referendum Campaign)

_-_53Fi1748_(Tony_Benn).jpg)

The influential Conservative Edward du Cann said that "the Labour party is hopelessly and irrevocably split and muddled over this issue".[13] The 'No' campaign included the left wing of the Labour Party, including the cabinet ministers Michael Foot, Tony Benn, Peter Shore, Eric Varley, and Barbara Castle who during the campaign famously said "They lured us into the market with the mirage of the market miracle". Some Labour 'No' supporters, including Varley, were on the right wing of the party, but most were from the left. The 'No' campaign also included a large number of Labour backbenchers; upon the division on a pro-EC White Paper about the renegotiation, 148 Labour MPs opposed their own government's measure, whereas only 138 supported it and 32 abstained.[3]

"Many Conservatives feel the European Community is not good for Britain ... The Conservative party is divided on it too", du Cann — head of the Conservatives' 1922 Committee — added,[13] although there were far fewer Eurosceptic figures in the Parliamentary Conservative Party in 1975 than there would be during later debates on Europe, such as the accession to the Maastricht Treaty. Most of the Ulster Unionist Party were for 'No' in the referendum, most prominently the former Conservative minister Enoch Powell, who after Benn was the second-most prominent anti-Marketeer in the campaign.[14] Other parties supporting the 'No' campaign included the Democratic Unionist Party, the Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru, and parties outside Parliament including the National Front and the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Official party positions

Conservative and Liberal Party conferences consistently supported EC membership for several years up to 1975. At a Labour Party conference on 26 April 1975, the Labour membership rejected continuing EC membership by almost a 2:1 margin. Tony Benn said, "We have had a conference and the decision is clear ... It is very clear that there now must be a move for the Labour Party to campaign." The majority of the Labour Party leadership was strongly for continuing membership, and the margin of the party vote was not a surprise, since only seven of forty-six trade unions present at the conference supported EC membership. Prior to the conference, the party had decided that if the conference voted by a margin of 2:1 or more in favour of a particular option, it would then support that position in the referendum campaign. Otherwise, the 'party machine' would remain neutral. Therefore, the Labour Party itself did not campaign on either side.

| For a 'Yes' vote | No official party position | For a 'No' vote |

|---|---|---|

|

The campaign, funding and media support

The government distributed pamphlets from the official Yes[16] and No[17] campaigns to every household in Britain, together with its own pamphlet which argued in support of EC membership.[18][19] According to this pamphlet, "the most important (issues in the renegotiation) were FOOD and MONEY and JOBS".

During the campaign, almost the entire mainstream national British press supported the 'Yes' campaign. The left-wing Morning Star was the only notable national daily to back the 'No' campaign. Television broadcasts were used by both campaigns, like party political broadcasts during general elections. They were broadcast simultaneously on all three terrestrial channels: BBC 1, BBC 2 and ITV. They attracted audiences of up to 20 million viewers. The 'Yes' campaign advertisements were thought to be much more effective, showing their speakers listening to and answering people's concerns, while the 'No' campaign's broadcasts featured speakers reading from an autocue.

The 'Yes' campaign enjoyed much more funding, thanks to the support of many British businesses and the Confederation of British Industry. According to the treasurer of the 'Yes' campaign, Alistair McAlpine, "The banks and big industrial companies put in very large sums of money". At the time, business was "overwhelmingly pro-European",[20] and Harold Wilson met several prominent industrialists to elicit support. It was common for pro-Europeans to convene across party and ideological lines with businessmen.[20] John Mills, the national agent of the 'No' campaign, recalled: "We were operating on a shoe-string compared to the Rolls Royce operation on the other side".[21] However, it was also the case that many civil society groups supported the 'Yes' campaign, including the National Farmers Union and some trade unions.

Much of the 'Yes' campaign focused on the credentials of its opponents. According to Alistair McAlpine, "The whole thrust of our campaign was to depict the anti-Marketeers as unreliable people – dangerous people who would lead you down the wrong path ... It wasn't so much that it was sensible to stay in, but that anybody who proposed that we came out was off their rocker or virtually Marxist."[21] Tony Benn said there had been "Half a million jobs lost in Britain and a huge increase in food prices as a direct result of our entry into the Common Market",[20] using his position as Secretary of State for Industry as an authority. His claims were ridiculed by the 'Yes' campaign and ministers; the Daily Mirror labelled Benn the "Minister of Fear", and other newspapers were similarly derisive. Ultimately, the 'No' campaign lacked a popular centrist figure to play the public leadership role for their campaign that Jenkins and Wilson fulfilled in the 'Yes' campaign.

Counting areas

The referendum was held nationally across all four countries of the United Kingdom as a single majority vote in 68 counting areas under the provisions of the Referendum Act, for which the then administrative counties of England and Wales and the then newly formed administrative regions of Scotland were used, with Northern Ireland as a single counting area.

The following table shows the breakdown of the voting areas for the referendum within the United Kingdom.

| Country | Counting areas |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | Referendum declaration; 68 counting areas |

| Constituent countries | Counting areas |

|---|---|

| England | 47 counting areas |

| Northern Ireland | Single counting area |

| Scotland | 12 counting areas |

| Wales | 8 counting areas |

Results

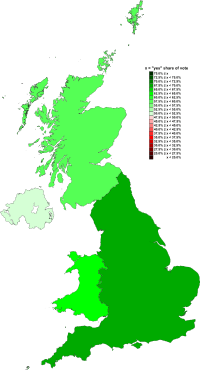

Voting in the referendum took place across the United Kingdom on Thursday 5 June between 07:00 and 22:00 BST. All counting areas started their counts the following day on Friday 6 June at 09:00 BST, and the final result was announced just before 23:00 BST by the Chief Counting Officer (CCO) Sir Philip Allen at Earls Court Exhibition Centre in London, after all 68 counting areas had declared their totals. With a national turnout of 64% across the United Kingdom, the target to secure a majority for the winning side was 12,951,598 votes. The result was a decisive endorsement of continued EC membership, which won by a huge majority of 8,908,508 votes (34.5%) over those who had voted to reject continued membership.

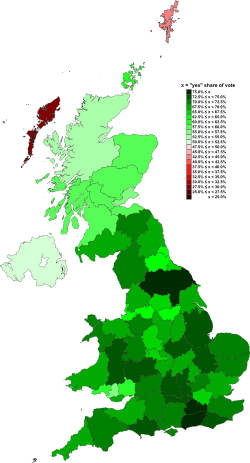

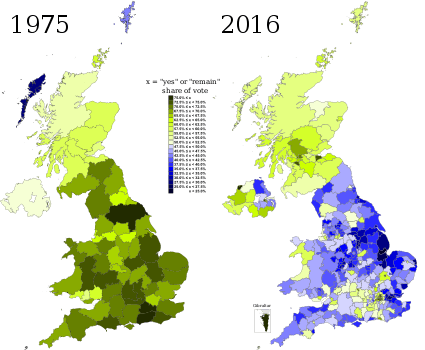

In total, over two-thirds of voters supported continued EC membership. 67.2 percent voted 'Yes' and 32.8 percent voted 'No'. At council level, support for EC membership was positively correlated with support for the Conservative Party and with average income. In contrast, poorer areas that supported Labour gave less support to the question. Approval was well above 60% in almost every council area in England and also in Wales, with the strongly Labour-supporting Mid Glamorgan being the exception. Scotland and Northern Ireland gave less support to the question than the British average. Once the voting areas had declared, their results were then relayed to Sir Philip Allen, the Chief Counting Officer, who later declared the final result.

All the counting areas within the United Kingdom returned large majority 'Yes' votes except for two Scottish regions, the Shetland Islands and the Western Isles, which returned majority votes in favour of 'No'.

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 17,378,581 | 67.23 |

| No | 8,470,073 | 32.77 |

| Valid votes | 25,848,654 | 99.78 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 54,540 | 0.22 |

| Total votes | 25,903,194 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters and turnout | 40,086,677 | 64.03 |

| Source: House of Commons Library[22] | ||

NOTE: Unusually for a referendum Yes was actually the no change (status quo) option.

| Yes: 17,378,581 (67.2%) |

No: 8,470,073 (32.8%) | ||

| ▲ | |||

Results by United Kingdom constituent countries

| Constituent country | Electorate | Turnout (%) | Yes | No | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| England | 33,356,208 | 64.6% | 14,918,009 | 68.7% | 6,812,052 | 31.3% |

| Wales | 2,011,136 | 66.7% | 869,135 | 64.8% | 472,071 | 35.2% |

| Scotland | 3,688,799 | 61.7% | 1,332,186 | 58.4% | 948,039 | 41.6% |

| Northern Ireland | 1,030,534 | 47.4% | 259,251 | 52.1% | 237,911 | 47.9% |

TV coverage

Both the BBC and ITV provided coverage throughout the following day, and the BBC programme was presented by David Dimbleby and David Butler. There were several programmes throughout the day. Part of the coverage was repeated to mark the 30th anniversary of the referendum in June 2005; it was also reshown to mark the 40th anniversary in June 2015 on the BBC Parliament channel, and was to be shown again to mark the 41st anniversary, ahead of the 2016 EU Referendum.[23] 41 years after the 1975 referendum, David Dimbleby also hosted the BBC's coverage as the UK voted to leave the EU.

Reactions to the result

On Friday 6 June 1975 at 18:30 BST the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, gave his reaction outside 10 Downing Street as counting continued, although by this point the result was clear:

'The verdict has been given by a vote with a bigger majority than has been received by any Government in any general election. Nobody in Britain or the wider world should have any doubt about its meaning. It was a free vote, without constraint, following a free democratic campaign conducted constructively and without rancour. It means that fourteen years of national argument are over. It means that all those who have had reservations about Britain's commitment should now join wholeheartedly with our partners in Europe, and our friends everywhere to meet the challenge confronting the whole nation.'

Enoch Powell gave this reaction to the result in a newspaper a few days after the referendum:

‘Never again by the necessity of an axiom, will an Englishman live for his country or die for his country: The country for which people live and die was obsolete and we have abolished it. Or not quite yet. No, not yet. The referendum is not a “verdict” after which the prisoner is hanged forthwith. It is no more than provisional … This will be so as long Parliament can alter or undo whatever that or any other Parliament has done. Hence those Golden words in the Government's Referendum pamphlet: “Our continued membership would depend on the continuing assent of Parliament”.’

Roy Jenkins said: "It puts the uncertainty behind us. It commits Britain to Europe; it commits us to playing an active, constructive and enthusiastic role in it." Tony Benn said: "When the British people speak, everyone, including members of Parliament, should tremble before their decision and that's certainly the spirit with which I accept the result of the referendum."[24] Jenkins was rewarded for successfully leading the campaign for Britain to remain a member of the European Communities when two years later he became the first and only British politician during the period of British membership from 1973 until 2020 to hold the post of President of the European Commission, which he held for four years from 1977–81.

The result strengthened Harold Wilson's tactical position, by securing a further post-election public expression of support for his policies. According to Cook and Francis (1979), ‘The left of his party had been appeased by the holding of a referendum, the right by its result’.[3] Following the result, the Labour Party and British trade unions themselves joined European institutions, such as the Socialist Group in the European Parliament, to which they had been reluctant to commit before public approval of EC membership.

In the House of Commons, the issue of Europe had been effectively settled for two years, until the debate about direct elections to the European Parliament began in 1977.

The result went on to provide a major pro-European mandate to politicians, particularly in the UK Parliament, for the next forty-one years until the 2016 EU membership referendum was held on Thursday 23 June 2016, when the UK voted by 51.9% to 48.1% to leave the European Union. On that occasion the relative difference of enthusiasm for membership was reversed, with England and Wales voting to leave, whilst Scotland, London and Northern Ireland voted to stay. At 11pm GMT on 31 January 2020, after 47 years of membership, the United Kingdom left the European Union.

Thirty-year rule

The question of sovereignty was discussed in an internal document of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO 30/1048) before the European Communities Act 1972, but was not available to the public until January 2002 under the thirty-year rule. Among "Areas of policy" listed "in which parliamentary freedom to legislate will be affected by entry into the European Communities" were: Customs duties, agriculture, free movement of labour, services and capital, transport, and social security for migrant workers. The document concluded (paragraph 26) that it was advisable to put the considerations of influence and power before those of formal sovereignty.[25]

See also

- Accession of the United Kingdom to the European Communities

- Treaty of Accession 1972

- European Communities Act 1972

- Brexit

- Referendums in the United Kingdom

- February 1974 United Kingdom general election

- October 1974 United Kingdom general election

- Withdrawal from the European Union

- 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum

Further reading

- Butler, D. and Kitzinger, U., The 1975 Referendum. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1996.

- Milward, A., ''The Rise and Fall of a National Strategy: The UK and The European Community: Volume 1. London and New York: Routledge, 2002; republished 2012.

- Saunders, Robert, Yes to Europe! The 1975 Referendum and Seventies Britain. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Wall, S., The Official History of Britain and the European Community, Volume II: From Rejection to Referendum, 1963-1975. London and New York: Routledge, 2013.

References

- The Labour Party (1974). Britain will win with Labour: Labour Party manifesto, October 1974. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- "1975 Referendum pamphlet".

- Cook, Chris; Francis, Mary (1979). The first European elections: A handbook and guide. London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 978-0-333-26575-8.

- "European Community". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 18 March 1975. col. 1456–1480.

- "Labour Party Manifesto 1983". 1983. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Crowson, Nicholas J. (1 January 2007). The Conservative Party and European integration since 1945 at the heart of Europe?. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 9780415400220. OCLC 493677870.

- "1970 Conservative Party Manifesto". conservativemanifesto.com.

- "The United Kingdom and the European Communities" (PDF). HM Government.

- Williamson, Adrian (5 May 2015). "The case for Brexit: lessons from the 1960s and 1970s". History & Policy. History & Policy. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Bogdanor, Vernon (2009). The New British Constitution. Oxford: Hart Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84113-671-4.

- Gay, Oonagh; Foster, David (25 November 2009). "Thresholds in Referendums". London: House of Commons Library. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- The seven Common Market opponents in the Cabinet were Michael Foot (Employment), Tony Benn (Industry), Peter Shore (Trade), Barbara Castle (Social Services), Eric Varley (Energy), William Ross (Scotland) and John Silkin (Planning and Local Government).

- "Conservatives favor remaining in market". Wilmington Morning Star. UPI. 4 June 1975. p. 5. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- Butler, David; Kitzinger, Uwe (1996). The 1975 referendum. Macmillan Press. pp. 178, 194. ISBN 9780333662908. OCLC 958137188.

- "After 41 years of shifting battlelines, the Brexit vote for Northern Ireland is a very tough one to call". Belfast Telegraph. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Why you should vote "Yes" | LSE Digital Library". digital.library.lse.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Why you should vote no | LSE Digital Library". digital.library.lse.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Britain's new deal in Europe | LSE Digital Library". digital.library.lse.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- HM Government (1975). Britain's new deal in Europe. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- Cockerell, Michael (4 June 2005). "How we were talked into joining Europe". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- Cockerell, Michael (4 June 2005). "How Britain first fell for Europe". BBC News. London. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- Miller, Vaughne (13 July 2015). "Research Briefings – The 1974–75 UK Renegotiation of EEC Membership and Referendum". House of Commons Library.

- "BBC One London - 6 June 1975 - BBC Genome". Genome.ch.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "1975: UK embraces Europe in referendum". BBC on This Day. London. 6 June 1975. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- FCO 30/1048, Legal and constitutional implications of UK entry into EEC (open from 1 January 2002.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United Kingdom European Communities referendum, 1975. |

- Examples of campaigning leaflets used during the 1975 referendum campaign

- Full text of the accession act

- House of Lords & the 1975 Referendum - UK Parliament Living Heritage

- Transcript of government pamphlet advocating to vote to stay in the EEC

- Article "Jan-Henrik Meyer, The 1975 referendum on Britain's continued membership in the EEC" on CVCE website

- Adrian Williamson, The case for Brexit: lessons from the 1960s and 1970s, History and Policy (2015).

- Article "Andrew Glencross (2015), Looking Back to Look Forward: 40 Years of Referendum Debate in Britain"