1914 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship Final

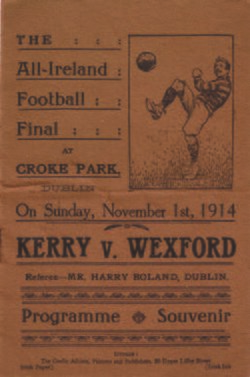

The 1914 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship Final was the 27th All-Ireland Final and the deciding match of the 1914 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship, an inter-county Gaelic football tournament for the top teams in Ireland. It was held at Croke Park in Dublin on 1 November. The game ended in a draw and a replay was held on 28 November.

| |||||||

| Event | 1914 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Date | 1 November 1914[1] | ||||||

| Venue | Croke Park, Dublin[2] | ||||||

| Referee | Harry Boland[1] (Dublin) | ||||||

| Attendance | 13,000[1] | ||||||

| |||||||

| Date | 28 November 1914[1] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venue | Croke Park, Dublin | ||||||

| Attendance | 20,000[1] | ||||||

| Weather | Windy[1] | ||||||

Harry Boland was the referee; he was later a close associate of Michael Collins during the Irish War of Independence, and fought and died on the anti-treaty side during the Irish Civil War.[1]

Wexford were captained by Seán O'Kennedy, whose brother Gus played at corner-forward.

First game

The final ended in a draw, necessitating a replay.[2] Wexford led 2–0 to 0–1 at half-time, but Kerry fought back to score five points in the second half.

The final score was 2–0 for Wexford and 1–3 for Kerry.[2] The Kerry point that brought them level was scored with only two minutes of play remaining.[2] Dick Fitzgerald got it. Wexford did not score in the second half and managed no points in the entire game.[2]

Over 26 trains were specially laid on for the final, coming from all parts of the island.[2]

Replay

The replay was held in windy conditions on 28 November.[1] The wind proved critical to the outcome of the game. Wexford's six points were scored during the first half when they had the wind behind them. Kerry's scored all of their two goals and three points during the second half.[1][3]

Special trains were also put on for the replay from destinations across the island: Belturbet, Cork, Cahersiveen, Dingle, Galway, Enniscorthy, New Ross, Shillelagh, Sligo, Waterford and Wexford.[1] These trains contained young men often "accompanied by their sisters and their sweethearts. The cramping and discomforts of a three to a six hours' train journey, in a stifling and vitiated atmosphere, was borne with the greatest of goodwill and forbearance. There was no complaining; jokes were cracked; humorous, patriotic, and sentimental songs were sung; and there was every sort of music, from bands and violins down to the tin whistle and mouth organ", said an analysis from a week later (5 December).[1]

The Dublin restaurants "did a good trade, and so did the public houses in certain districts. But there was practically no drunkenness, disorderly conduct, or horseplay on the streets".[1]

References

- Mullally, Una (14 July 2019). "As the summer football season heats up, let's take a trip back to 1914 for the 27th All-Ireland Final". The Irish Times. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- "Wexford and Kerry draw All-Ireland Football Final". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- High Ball magazine, issue #6, 1998.