Zygacine

Zygacine is a steroidal alkaloid of the genera Toxicoscordion, Zigadenus, Stenanthium and Anticlea of the family Melanthiaceae.[1] These plants are commonly known and generally referred to as death camas. Death camas is prevalent throughout North America and is frequently the source of poisoning for outdoorsmen and livestock due to its resemblance to other edible plants such as the wild onion.[1] Despite this resemblance, the death camas plant lacks the distinct onion odor and is bitter to taste.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

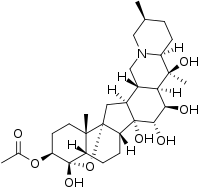

| IUPAC name

(5ξ,8ξ,9ξ,12ξ,14ξ)-4,14,15,16,20-Pentahydroxy-4,9-epoxycevan-3-yl acetate | |

| Other names

Cevane-3β,4β,14,15α,16β,20-hexol, 4,9-epoxy-, 3-acetate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| Properties | |

| C29H45NO8 | |

| Molar mass | 535.678 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

The effects of zygacine consumption are lethal. Symptoms in humans include nausea, vomiting, slowed heart rate, low blood pressure and ataxia.[2] Poisoned animals suffer from loss of appetite, lack of coordination, digestive and excretory disorders, labored breathing, racing heartbeat and frequently death.[2]

Suggested treatment of poisoning in humans include administering dopamine and atropine to the patient.[3] For animals, treatment consists of atropine, picrotoxin and activated charcoal.[4]

History

Scientists first attempted to determine the toxic ingredient(s) of alkaloid extracts of Zygadenus plants in 1913.[5] They were able to isolate zygadenine, the alkamine present in alkaloids of the genus Zigadenus.[5] The minimal pharmacological activity of zygadenine led to subsequent investigations of Zygadenus venenosus and Zygadenus paniculatus which revealed that zygacine was one of the primary toxic components.[5] Although it was first isolated in 1913, the structure and configuration of zygacine weren't reported until 1959.[6]

Zygacine poisoning via ingestion of death camas had been reported as early as the nineteenth century when Native Americans sold the death camas as food to railroad workers who died after eating the bulbs. It has been for many years - and continues to be - responsible for the poisonings and deaths of many types of livestock including sheep, cattle, horses, pigs and fowl.[7] A one-time loss of 500 sheep was reported in 1964[8] and in 1987, 250 sheep died from death camas poisoning.[9] Poisonings generally occur in the early spring when the death camas plant is most abundant and other food sources for livestock are limited.[10] Sheep seem to be poisoned most often due to their grazing behavior as they pull up and consume the entire plant.[2] Moist conditions are more conducive to cattle poisoning as it makes it easier to extract the plant from the soil.[2] Outdoorsmen have also fallen victim to zygacine poisoning by mistaking the death camas for other edible plants. In 1994, a man presented to the emergency department with gastrointestinal symptoms, a depressed heart rate and low blood pressure after inadvertently eating plant material derived from a species of Zigadenus.[11] He recovered after being treated.

Toxicity

Zygacine is a highly potent compound with an LD50 of 2.0 +/- 0.2 mg/kg when administered intravenously and 132 +/- 21 mg/kg when administered orally to mice.[10] The lethal dose conversions for a 60 kg human, 600 kg cow and 80 kg sheep are included in the table below.

| Subject | Human (60 kg) | Cattle (600 kg) | Sheep (80 kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV Administration | 108 mg - 132 mg | 1.08 g - 1.32 g | 144 mg - 176 mg |

| Oral Administration | 6.66 g - 9.18 g | 66.60 g - 91.80 g | 8.88 g - 12.24 g |

General symptoms of zygacine poisoning among humans and animals alike include but are not limited to gastrointestinal and cardiovascular ailments such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and irregular heartbeat.[11]

Within an hour of ingesting the toxic death camas plant, a human will begin to experience nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping and diarrhea.[11] Other symptoms include low heart rate and blood pressure as well as ataxia and muscle spasms.[11]

Initial signs of zygacine poisoning in animals include frothy salivation around the mouth, followed by nausea and vomiting.[12] Severely poisoned animals will suffer from a loss in appetite, lack of coordination and depression.[2] Sheep, in particular, will stand with their heads and ears dropped with their backs are arched.[2] Intestinal peristalsis, a condition characterized by involuntary movement of the muscles in the digestive tract, results in frequent defecation and urination.[12] Fatally poisoned animals develop a weak and rapid pulse and labored breathing.[12] The shuddering struggle to breathe may be confused with convulsions.[12]

Mechanism

Zygacine is a steroidal alkaloid of the veratrum type.[13] Veratrum alkaloid compounds act by attaching to voltage-gated sodium ion channels, altering their permeability.[14] Veratrum alkaloids cause affected sodium channels to reactivated 1000x slower than unaffected channels.[14] They also block inactivation of sodium channels and change their activation threshold so they remain open even at resting potential.[14] As a result, sodium concentrations within the cell rise, leading to increased nerve and muscle excitability.[11] This biochemical activity causes muscle contractions, repetitive firing of the nerves and an irregular heart rhythm from stimulation of vagal nerves which control the parasympathetic functions of the heart, lungs and digestive tract.[11]

Treatment

There is no antidote for zygacine poisoning so only the symptoms arising from poisoning in humans are usually treated, of which bradycardia and hypotension are prioritized. These symptoms are initially treated with atropine, a muscarinic receptor agonist.[3] In a case study in which atropine was not sufficient, hypotension and bradcycardia were successfully treated using dopamine.[15] Dopamine increases renal sodium excretion, blood pressure and the heart rate.[16]

For animals, reported effective treatment of zygacine poisoning consists of injection of 2 mg of atropine sulfate and 8 mg of picrotoxin per 45 kg of body weight.[4] Intravenous fluid therapy is used to increase blood pressure.[4] A stomach tube can be used to relieve stomach pressure in bloated animals.[4]

References

- "Death Camas, Toxicoscordion venenosum". calscape.org. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- Stegelmeier, Bryan L., Reuel Field, Kip E. Panter, Jeffery O. Hall, Kevin D. Welch, James A. Pfister, Dale R. Gardner et al. "Selected poisonous plants affecting animal and human health." In Haschek and Rousseaux's Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology (Third Edition), pp. 1259-1314. 2013.

- "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- "Guide to Poisonous Plants – College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences – Colorado State University". csuvth.colostate.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- Kupchan, S. Morris. "Veratrum alkaloids. XXX. 1 The structure and configuration of zygadenine2." Journal of the American Chemical Society 81, no. 8 (1959): 1925-1928.

- Majak, Walter, Ruth E. McDiarmid, Walter Cristofoli, Fang Sun, and Michael Benn. "Content of zygacine in Zygadenus venenosus at different stages of growth." Phytochemistry 31, no. 10 (1992): 3417-3418.

- Panter, K. E., and L. F. James. "Death camas--early grazing can be hazardous." Rangelands Archives 11, no. 4 (1989): 147-149.

- Kingsbury, John M. "Poisonous plants of the United States and Canada." Soil Science 98, no. 5 (1964): 349.

- Panter, K.E., M.H. Raiphs, R.A. Smart, and B. Duelke. 1987. Death camas poisoning in sheep: A case report. Vet, and Human Tox. 29:45-48.

- Welch, K. D.; Panter, K. E.; Gardner, D. R.; Stegelmeier, B. L.; Green, B. T.; Pfister, J. A.; Cook, D. (2011-05-01). "The acute toxicity of the death camas (Zigadenus species) alkaloid zygacine in mice, including the effect of methyllycaconitine coadministration on zygacine toxicity". Journal of Animal Science. 89 (5): 1650–1657. doi:10.2527/jas.2010-3444. ISSN 1525-3163. PMID 21521823.

- Heilpern, Katherine L (1995-02-01). "Zigadenus Poisoning". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 25 (2): 259–262. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70336-5. PMID 7832360.

- Panter, Kip E., Kevin D. Welch, and Dale R. Gardner. "Poisonous plants: biomarkers for diagnosis." In Biomarkers in Toxicology, pp. 563-589. 2014.

- "Cornell University Department of Animal Science". poisonousplants.ansci.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- Furbee, Brent. "Neurotoxic plants." In Clinical Neurotoxicology: Syndromes, Substances, Environments. Elsevier Inc., 2009.

- West, Patrick, and B. Zane Horowitz. "Zigadenus poisoning treated with atropine and dopamine." Journal of Medical Toxicology 5, no. 4 (2009): 214.

- Bhatt-Mehta, Varsha; Nahata, Milap C. (1989-09-10). "Dopamine and Dobutamine in Pediatric Therapy". Pharmacotherapy: the Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 9 (5): 303–314.