Zrinski family

Zrinski (Hungarian: Zrínyi) was a Croatian-Hungarian noble family,[5][6][7] a cadet branch of the Croatian noble tribe of Šubić, influential during the period in history marked by the Ottoman wars in Europe in the Kingdom of Croatia's union with the Kingdom of Hungary and in the later Kingdom of Croatia as a part Habsburg Monarchy. Notable members of this family were Bans of Croatia, considered national heroes in both Croatia and Hungary, and were particularly celebrated during the period of Romanticism, a movement which was called Zrinijada in Croatia.

| Zrinski | |

|---|---|

| Parent house | House of Šubić |

| Country | Kingdom of Croatia (in union with Hungary) Kingdom of Hungary |

| Founded | 1347[1] |

| Founder | Juraj I Zrinski (although his uncle Grgur II Šubić of Bribir was the first lord of Zrin, acting on behalf of his minor nephew, Juraj III Šubić of Bribir was the first to call himself Zrinski)[2] |

| Final ruler | Ivan Antun Zrinski[2] |

| Titles | Count of Zrin[3][4] Ban of Croatia[1][2] |

| Dissolution | 1703[1] |

History

The Zrinski (Hungarian: Zrínyi), meaning "those of Zrin", are a branch of the Šubić family, which arose when king Louis I of Hungary needed some of the Šubićs' fortresses for his coming wars against Venice, and the city of Zadar in particular.

In 1347, Louis I took their estates around Bribir in Dalmatia and gave them the Zrin estate with Zrin Castle, located south of the modern city of Petrinja and west of Hrvatska Kostajnica, in what was then Slavonia and is today the Croatian region of Banovina.[8] Since that time they are known as the "Counts of Zrin" in historical sources.[1][3][4] Later, their power steadily increased, so that they acquired the territory between the rivers Krka and Zrmanja and the sea by the 13th century. At the outset of the 14th century, Paul I Šubić of Bribir was the longest-ruling Ban of Croatia (1275–1312), as well as lord of all of Bosnia (1305–1312). His son was Paul II Šubić of Bribir.

Paul I's grandson was the first Zrinski, Juraj III. Šubić of Bribir, who took the title Juraj I. Zrinski. His cousin, countess Jelena Šubić, was at the same time married to Vladislav Kotromanić. Their first-born child, Tvrtko I, became the Ban of Bosnia and from 1377 the King of Bosnia. Their niece and adopted daughter, Elizabeta Kotromanić (Elisabeth of Bosnia), married Louis I the Great. Elizabeth's and Louis' daughters succeeded their father and became queens in their own right, as Mary of Hungary and Jadwiga of Poland.

The Zrinskis were Croats and played a crucial role in the history of the Croatian state, both before their arrival in Zrin and later. On the other hand, they are also identified as hungarus or natio hungarica, which means "somebody from the Kingdom of Hungary", regardless of the language spoken and nationality. They were among many noble families in the Kingdom of Hungary. In the 16th century, Ban Nikola IV Zrinski gained dominion over Međimurje County in the northernmost part of Croatia with its capital Čakovec. Because they lived, worked, and intermarried with nobility from all parts of the multiethnic kingdom, it was natural and expected that they should be fluent in four or five languages. It is certain, that Nikola Zrinski spoke at least Croatian, Hungarian, Italian, Turkish and of course Latin. It is of interest that he was the most prominent Hungarian poet in the 17th century, while his brother Peter is known for his poems in Croatian language.

Among the many notable personalities of the family, there were a few women. Katarina Zrinska (1625–1673), a noted poet, was born in the Frankopan family, and, having married Petar Zrinski, became the member of the Zrinski family. Her daughter, Jelena Zrinska, was the wife of Francis I Rákóczi, the prince of Transylvania.

The Zrinski and the Frankopan families were the two most prominent noble families in Croatia in 16th and 17th century and they both perished in 1671 when Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan were charged with treason by the Emperor Leopold I, owing it to their role in the so-called Zrinski-Frankopan Plot (in Hungarian historiography called the Wesselényi Plot), and executed in Wiener Neustadt. The estates of Zrinski and Frankopan families were confiscated and their surviving members relocated.

The remains of Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan were transferred from Austria to Croatia in 1919 and buried in the Zagreb Cathedral.

The last male Zrinski descendants were Adam Zrinski (1662–1691), son of Nikola Zrinski, a Habsburg Monarchy army lieutenant-colonel. He inherited from his father the large and valuable "Bibliotheca Zriniana". Died in the Battle of Slankamen in 1691, accidentally shot in his back by one of his fellow soldiers. Ivan Antun Zrinski (1654–1703), son of Petar Zrinski and Katarina Zrinska, was Habsburg army officer, who was accused of high treason and died after years in dungeons.

Family's survival

Although was generally considered that the family became extinct, it still remains a matter of debate.[9] According to oral tradition, there was a Zrinski member, Martin Zrinski (1462–1508), who was hidden by the Habsburgs in a Venetian army as an officer of the cavalry in the 16th century and the Venetian Republic sent him as Martino Zdrin (or Sdrigna) to the island of Cephalonia in Greece where he eventually settled, and the family was recorded in the gold book of island's nobility as Sdrin, Sdrinia, Sdrigna, and Zrin. The family Sdrinias, with almost the same coat of arms as the Zrinski family, still exists in Greece and was accepted in the Croatian Nobility Association with the highest noble status.[10][11] The survival is supported by seven letters (two written by Maria Sdrin) and photographs from Greece signed by Contessa & Conte K. Sdrin and Conte Gerasimo N. Sdrini, and on behind Suvenire S. N. Sdriny Marsullela 7/20/6 1913. Madame Evangelini Tsimara Mavrata Ceffalonia.[9]

Bans

The family produced four Bans of Croatia (viceroys):

- Nikola IV Zrinski (Hungarian: Szigeti Zrínyi Miklós; 1508–1566), ban from 1542 unil 1556

- Juraj V Zrinski (Hungarian: Zrínyi György; 1599–1626), ban from 1622 until 1626

- Nikola VII Zrinski (Hungarian: Zrínyi Miklós; 1620–1664), ban from 1647 until 1664

- Petar Zrinski (Hungarian: Zrínyi Péter; 1621–1671), ban from 1665 until 1670

Legacy of Zrinski

Literature and theatre

- Ivan Zajc, opera Nikola Šubić Zrinski (famous aria U boj, u boj)

- Eugen Kumičić: Urota zrinsko-frankopanska

Paintings

Zrinski family was often topic in the paintings of Oton Iveković.

- Nikola Zrinski pred Sigetom

- Oproštaj Zrinskog i Frankopana od Katarine Zrinske

- Juriš Nikole Zrinskog iz Sigeta

- Miklós Barabás: Miklós Zrinyi

- Viktor Madarász: Miklós Zrinyi

Sculptures

- in the Citadel in Budapest

Engineering

- 43M Zrínyi: armoured assault gun in World War II, named after Nikola IV Zrinski

Navy

- The SMS Zrínyi, a Radetzky-class pre-dreadnought battleship (Schlachtschiff) of the Austro-Hungarian Navy (K.u.K. Kriegsmarine)

Holdings

Some castles which were propriety of the family. Some castles, like Dubovac, Kraljevica, Ozalj, Severin na Kupi and others were jointly owned with Frankopan family.

- Zrin Castle, once a seat of the family on mainland

Brezovica Castle

Brezovica Castle- Brod na Kupi Castle

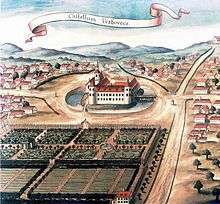

- Fortress Kastel

Lukavec Castle

Lukavec Castle Vrbovec Castle

Vrbovec Castle

See also

References

- "Obitelj Zrinski". ARHiNET (digital archive information system of Croatian State Archives). Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "Zrinski". Croatian Encyclopedia by Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography (online edition). Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "Von Zrin (Zrinski)". Arcanum Database Ltd. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "Zrinski, Petar Graf". Biographisches Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas (online edition). Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- Piotr Stefan Wandycz: The Price of Freedom: A History of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present, 2nd edition, Routledge, London, 1992

- Dominic Baker-Smith, A. J. Hoenselaars, Arthur F. Kinney: Challenging Humanism: Essays in Honor of Dominic Baker-Smith, Rosemont Publishing & Printing Corp., 2010

- Marcel Cornis-Pope, John Neubauer (editors): History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe, Volume 1, John-Benjamin Publishing Company, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, 2004

- "Zrínyi (croato Zrinski)". Treccani - Enciclopedia Italiana (online edition). Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- Ivan Kosić (2012). "Bibliotheca Zriniana". Kaj: Literature, Art and Culture Periodical. 45 (4–5): 58. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- "Obitelj Sdrinias". Croatian Nobility Association (plemstvo.hr). Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "Posljednji Šubići Zrinski još žive u Grčkoj!" [The last Šubić Zrinski still live in Greece!]. Večernji list. June 4, 2005. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zrinski family. |

- Zrinski stamps

- Marek, Miroslav. "hung/zrinyi.html". genealogy.euweb.cz.

- Obitelj Zrinski at arhinet.arhiv.hr (in Croatian)