Nikola IV Zrinski

Nikola IV Zrinski or Miklós IV Zrínyi (Hungarian: Zrínyi Miklós, Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈzriːɲi ˈmikloːʃ]; 1507/1508 – 7 September 1566), also commonly known as Nikola Šubić Zrinski (Croatian pronunciation: [nǐkɔla ʃûbitɕ zrîːɲskiː][1]),[nb 1] was a Croatian-Hungarian nobleman and general, Ban of Croatia from 1542 until 1556, royal master of the treasury from 1557 until 1566, and a descendant of the Croatian noble families Zrinski and Kurjaković. During his lifetime the Zrinski family became the most powerful noble family in the Kingdom of Croatia.

Nikola IV Zrinski Miklós IV Zrínyi | |

|---|---|

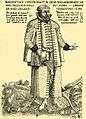

A 16th-century engraving by Matthias Zündt | |

| Ban (Viceroy) of Croatia | |

| In office 24 December 1542 – 27 December 1556 | |

| Preceded by | Petar Keglević |

| Succeeded by | Péter Erdődy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1508 Zrin, Kingdom of Croatia |

| Died | 7 September 1566 (c. 58) Szigetvár, Kingdom of Hungary |

| Resting place | Pauline monastery in Sveta Jelena, Croatia |

| Spouse(s) | Katarina Frankopan Eva Rosenberg |

| Children | Ivan II, Jelena, Katarina, Juraj IV, Doroteja, Uršula, Barbara, Margareta, Magdalena, Ana, Kristofor, Nikola V, Ivan III |

| Parents | Nikola III Zrinski Jelena Karlović |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | Siege of Pest (1542) Battle of Babócsa (1556) Battle of Moslavina (1562) Siege of Szigetvár (1566) |

Zrinski became well known across Europe for his involvement in the Siege of Szigetvár (1566), where he heroically died stopping Ottoman Empire's Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent's advance towards Vienna. The importance of the battle was considered so great that the French clergyman and statesman Cardinal Richelieu described it as "the battle that saved civilization".[5] Zrinski became considered a role model of a faithful and sacrificial warrior, Christian hero as well as a national hero in both Croatia and Hungary, and is often portrayed in artworks.

Early life

Nikola was an ethnic Croat.[6][7][8] He was born as one of the six children of Nikola III of the Zrinski family from the noble tribe of Šubić, and of Jelena Karlović, sister of future Croatian Ban Ivan Karlović of the Kurjaković family from the noble tribe of Gusić.[4] His birthplace is unknown, but it is generally considered to have been Zrin Castle. The same is about his birth date, for which different primary sources give dates ranging between 1507, 1508 and 1518, but according to them and other evidence it is considered to have been in 1507 or 1508,[9] with 1508 most often cited in scholarship.[10]

Activities

Zrinski already distinguished himself in the early twenties during the Siege of Vienna in 1529,[4][9] for which was awarded with a horse and golden chain.[11] After the death of his father Nikola III in 1534, Nikola IV with older brother Ivan I inherited estates in Pounje, and they simultaneously started to fortify them as well as make contacts with the Ottomans, to whom they paid a yearly tribute like their father.[9] However, between 1537 and 1540 they started fighting against Gazi Husrev-beg's forces for the control of fort Dubica.[12]

In January 1539, Zrinski murdered the Imperial Army commander Johann Katzianer at Fortress Kostajnica because Katzianer had deserted the King Ferdinand I Habsburg, had started to conspire in favor of throne contestant John Zápolya, and had cooperated with the Ottomans.[4][9][12] During the following year, the estates of the Zrinski brothers were again attacked by the Ottomans. By June 1540, they fought the combined forces of Husrev-beg, Murat-beg Tardić and Mehmed-beg Jahjapašić, and because of a lack of sufficient help from the Austrian military, the fortress Kostajnica was temporarily lost to the Turks. Zrin Castle and Gvozdansko Castle managed to hold up, but the mining sites and others were devastated.[12] They successfully repelled the attack however, and from that moment on the Zrinski family continuously fought against the Ottomans.[4][9]

In 1541, together with his older brother Ivan I, Nikola received large possessions of the Vrana Priory in Croatia and Hungary by Ferdinand I, but with the death of his brother in the same year, he also became the only successor to the estates of the Zrinski family.[4][13] In 1542, according to Antun Vramec, he saved the Imperial Army forces from defeat at the Siege of Pest by intervening with 400 Croats, for which service he was appointed Ban of Croatia, a position which held until 1556.[4] During this period he frequently went to Gvozdansko Castle in order to inspect the silver mines and the mint, like in other forts in the Pounje and Pokuplje basins.[4] As compensation for him fighting against the Ottomans, he was granted the whole area of Međimurje (Muraköz) on 12 March 1546 by King Ferdinand I, hence the center of the Zrinski family has moved from Zrin Castle to the city of Čakovec, where he significantly rearranged the existing Čakovec Castle.[4][9][14] In 1549 he was given the right to collect tax from the subjects by himself, and in 1561 the right to freely settle serfs on his estates.[9]

In 1556, Zrinski won a series of victories over the Ottomans, culminating in the battle of Babócsa, and thus preventing the fall of Szigetvár.[9][14] However, since he was unsatisfied with the amount of resources for defense, he voluntary withdrew from his position as Ban of Croatia.[9][15] In the next year, 1557, he was titled Master of the treasury, a royal office position which he held until death, becoming once again one of the fifteen most influential persons in the Kingdom of Hungary.[4] Additionally, he served as a captain of Croatian light cavalry (1550–1560), captain of Szigetvár and commander of the Transdanubian border from 1561 and 1563 respectively and until his death.[4][9]

In 1563, on the coronation of Emperor Maximilian as king of Hungary, Zrinski attended the ceremony at the head of 3000 Croatian and Magyar mounted noblemen, in the hope of obtaining the highest dignity of Palatine, vacant by the death of Tamás Nádasdy.[9][16] Some historians like Géza Pálffy consider he did manage to obtain it.[9] In the next year, he hastened southwards to defend the frontier, and defeated the Ottomans at Szeged. In 1565, Zrinski brought a copy of the Holy Crown of Hungary to Vienna for the funeral ceremony of Ferdinand I.[9]

Death

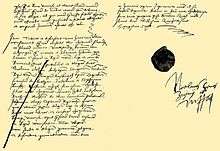

In the spring of 1566, Zrinski was located in Szigetvár, a strategic fortress for the defense of the shortest route to Vienna, when the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent went with a large army for a second attempt to conquer Vienna, but first decided to capture Szigetvár. Zrinski was informed by the new king, Maximilian II, that he could either remain or leave it to another captain, but in an April, 23rd letter, Zrinski wrote that it was his will to remain because many thousands of people depend on the fortress's survival, and he started to strategically prepare to confront the Sultan.[9][17] Suleiman's forces reached Belgrade on 27 June after a forty-nine-day march. Learning of Zrinski's success in an attack upon a Turkish forces at Siklós in July, destroying several detachments,[8] Suleiman decided to postpone his attack on Eger and instead attack Zrinski's fortress at Szigetvár to eliminate him as a threat.[18][19]

For over a month from 5 August to 7 September,[8] with a small force of roughly 2,300–2,500 soldiers, mostly Croats,[10] heroically defended the small fortress of Szigetvár against the whole Ottoman army of over 100,000 soldiers and 300 cannons, led by Suleiman in person. They did so without reinforcements which were promised by the Hungarian–Croatian King,[17] and against Suleiman's offer of Croatian land to Zrinski.[8] The Siege of Szigetvár ended with every remaining member of the garrison in a desperate and suicidal charge from the fortress led by Zrinski on 7 September 1566.[17][20] Suleiman also died, but from natural causes, one day before the Ottomans won the siege.[21] As Ottoman forces had suffered heavy casualties during the siege of Szigetvár, the army only managed to additionally capture the nearby fort Babócsa before Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha withdrew the army and ended the Ottoman conquest.[9]

According to historical sources, Zrinski decided to be dressed in a hat and nice suit rather than a helmet and armour during his final charge, and chose to have his father's sabre in hand, so that he it could be said that he had "bared all that I was judged by God's judgment",[16] and offered one hundred gold coins as a reward for the Ottoman soldier who cut off his head. He was shot by a Janissary with a musket in the head and chest, while by other accounts it was first by a musket in the chest and then an arrow to the head.[9][22] Is is considered that his head was sent by Mehmed Pasha to Budin Pasha Sokullu Mustafa,[9][23] or to new Sultan Selim II,[24] but eventually, the head was buried by son Juraj IV Zrinski, Boldizsár Batthyány and Ferenc Tahy in September 1566 at the Pauline monastery in Sveta Jelena, Šenkovec, Croatia.[9][23] It is uncertain what happened to his body, it could have been burned or buried near the battlefield, but according to most sources it is considered to have been buried by former Muslim captive Mustafa Vilić from Banja Luka because he had been well treated by Zrinski.[9][25][26]

In Međimurje County Museum in Čakovec are preserved remains of the tombstone of a member of the Zrinski family, which most probably belonged to Nikola IV, and under which his head was likely buried.[9][25] Preserved in Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna are the sabre, helmet, and possibly the silk robe with decorative gold thread which were created and wore by Zrinski during the 1563 coronation of Maximilian II. They were initially collected by Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria at Ambras Castle in the 16th century.[16]

Marriage

Zrinski married twice, first in 1543 with Katarina Frankopan (d. 1561) and then Eva Rosenberg (1537–1591) in 1564.[9][27] Due to his marriage to Katarina Frankopan, a sister of Count Stjepan Frankopan of Ozalj (d. 1577), her vast estates, including Ozalj and part of littoral cities like Bakar, became at his disposal in 1550 due to the inheritance contract.[4][13] With his marriage to Eva Rosenberg, a sister of William of Rosenberg the Burgrave of Bohemia, he managed to connect with one of the most notable Czech noble families and, according to Géza Pálffy, to the highest elite of the Kingdom of Hungary.[9] His marriages and his service during his lifetime managed to elevate the Zrinski family to become the most powerful noble family in the Kingdom of Croatia.[13]

Children

With Katarina and Eva, Zrinski had thirteen children, Ivan I, Jelena, Katarina, Juraj IV, Doroteja, Uršula, Barbara, Margareta, Magdalena, Ana, Kristofor, Nikola V, and Ivan II, of whom most notably was his successor Juraj IV Zrinski.[4] One of the younger sons married a lady from the noble Czech Kolowrat family.[12] According to Dóra Bobory "it is possible to detect an increasingly conscious marriage policy within the Zrinski family, where all the daughters of Miklos married well, and where father himself chose his spouses wisely". Most notably, Doroteja became the wife of Boldizsár Batthyány in 1566, Katarina wife of Imre Forgách in 1576, while some other two daughters married into Thurzó family,[12] specifically Katarina was previously (1562) married to Ferenc Thurzó being the mother of future Palatine of Hungary, György Thurzó.[28] For some of them, Uršula, Katarina, and Doroteja is known that were educated at Güssing.[15]

Legacy

Zrinski's heroic act at the siege of Szigetvár made him a well known European Christian hero, a defender and savior of Christendom, and "a model of a faithful and sacrificial warrior in the service of his ruler". He was also compared to Leonidas I. His cult of heroism was especially preserved among the Croats, Hungarians, and Slovaks. In Croatia, it also represented a symbol of Croatian identity, directed against Ottoman, Austrian and Hungarian political influence.[9][29][30] Similarly, he gained some popularity during the Polish struggle for independence in second half of the 19th century and early 20th century.[31] According to historians like Ágnes R. Várkonyi and Alojzije Jembrih, Zrinski had an "exceptional military talent, was a successful businessman, politician with a concept, and an endlessly passionate person".[22]

He was remembered in a first-hand report Podsjedanje i osvojenje Sigeta (1568) by Zrinski's scribe and chamberlain Franjo Črnko,[32] which was immediately translated in Latin by Samuel Budina and published in the same year titled Historia Sigethi, totius Sclavoniae fortissimi propugnaculi..., with the second edition (1587) edited by Petrus Albinus.[22] It was also translated into German, Italian, Spanish and other languages.[33] Other works include a historical epic Vazetje Sigeta grada (1584) by Brne Karnarutić,[32] and most prominently Hungarian epic poem The Siege of Sziget (1651) by his great-grandson Nikola VII Zrinski and its partial Croatian variation Adrianskoga mora Sirena (1660) by great-grandson Petar Zrinski.[10][34] In the epic poem, the elder Zrinski is the main hero and has assured Zrinski's place in Hungarian culture as it remains in print today and is considered one of the landmarks of Hungarian literature.[35] Compared to the Hungarian poem, which is an exception in Hungarian literature, the Croatian variation fits the Croatian literature tradition.[36] Vladislav Menčetić's Trublja slovinska (1665) is the first Ragusan literature work that introduces the idea of antemurale Christianitatis for Croatian territories and celebrates Zrinski as a hero.[37] Pavao Ritter Vitezović also wrote a related epic poem Odiljenje sigetsko (1684).[38]

In the 18th century, his heroic act inspired school dramas in Jesuit Gymnasiums, including Andreas Friz's Nicolai Zriny ad Szigethum victoria (1738).[22][39][40] The German author Theodor Körner wrote a tragedy, Zriny: Ein Trauerspiel (1812),[41] after which August von Adelburg Abramović wrote the libretto for his opera Zrinyi (1868).[42] The Croatian composer Ivan Zajc created an opera titled Nikola Šubić Zrinski (1876), as a patriotic work which is still performed regularly today. It includes an aria "U boj, u boj",[9] which is regularly performed at the Japanese Kwansei Gakuin University since the World War I.[43]

Since the 16th century, Zrinski featured in many engravings and paintings, of him as a portrait or during the siege mostly as leading the charge, like by Matthias Zündt, Miklós Barabás, Viktor Madarász, Mikoláš Aleš, Bela Čikoš Sesija and Oton Iveković among others.[44] In 1914, the Czech painter Alphonse Mucha dedicated to Zrinski the painting titled Defense of Sziget against the Turks by Nicholas Zrinsky: The Shield of Christendom from his The Slav Epic cycle.

By the imperial resolution of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria on 28 February 1863, Zrinski was included in the list of "Austria's most famous warlords and field commanders worthy of eternal emulation", in whose honor and memory was built a life-size statue of Carrara marble at the Museum of Military History, Vienna, in 1865 by sculptor Nikolaus Vay (1828-1886).[45] There also exist several sculptures and busts of Zrinski in Zagreb, Čakovec and Šenkovec in Croatia, Budapest and Szigetvár in Hungary, and Heldenberg in Austria among others. Parks in Zagreb (see Nikola Šubić Zrinski Square), Koprivnica and Križevci among others are named after him.[9]

In 1866 was held a solemn commemoration of the 300th anniversary of Zrinski's death in Croatia.[22] In commemoration of the 450th anniversary of the siege of Szigetvár (1566), the year 2016 was declared a memorial year of Nikola Zrinski and the siege of Szigetvár in Croatia and Hungary. On that occasion were held various cultural and artistic events,[22] published many papers and books as well as organized scientific conferences in Zagreb, Čakovec, Vienna, and Pécs.[46]

The Order of Nikola Šubić Zrinski is the eighth-ranked honour order given by the Republic of Croatia, awarded since 1995 to Croatian or foreign citizens for acts of heroism.[47]

Gallery

Sabre and helmet of Zrinski at an exhibition in Međimurje County Museum on the 450th anniversary of the siege of Szigetvár, 2016

Sabre and helmet of Zrinski at an exhibition in Međimurje County Museum on the 450th anniversary of the siege of Szigetvár, 2016 An engraving by Jenichen Boldizsár, 1566

An engraving by Jenichen Boldizsár, 1566 The apotheosis of Miklós Zrínyi, unknown author, 16th century

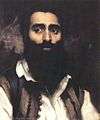

The apotheosis of Miklós Zrínyi, unknown author, 16th century A funeral portrait, unknown author, 17th century or earlier

A funeral portrait, unknown author, 17th century or earlier A portrait at East Slovak Museum, 18th century

A portrait at East Slovak Museum, 18th century A portrait by Miklós Barabás, 1842

A portrait by Miklós Barabás, 1842 A portrait by Viktor Madarász, 1858

A portrait by Viktor Madarász, 1858 A portrait by Julije Hühn, 1866

A portrait by Julije Hühn, 1866.jpg) A portrait by Mikoláš Aleš, 1878

A portrait by Mikoláš Aleš, 1878 A portrait by Oton Iveković, 19th century

A portrait by Oton Iveković, 19th century A portrait by J. F. Mucke, 19th century

A portrait by J. F. Mucke, 19th century.png) A portrait in Wiener Bilder, 1907

A portrait in Wiener Bilder, 1907

A sculpture of Zrinski in Čakovec

A sculpture of Zrinski in Čakovec- A sculpture of Zrinski at Kodály körönd, in Budapest

A modern sculpture of Zrinski in Szigetvár

A modern sculpture of Zrinski in Szigetvár A bust of Zrinski at Hungarian-Turkish Friendship Park, in Szigetvár

A bust of Zrinski at Hungarian-Turkish Friendship Park, in Szigetvár A bust of Zrinski in Szigetvár

A bust of Zrinski in Szigetvár A bust of Zrinski in Heldenberg Memorial

A bust of Zrinski in Heldenberg Memorial A bust of Zrinski for the 450th anniversary of the siege of Szigetvár, at Šenkovec, 2016

A bust of Zrinski for the 450th anniversary of the siege of Szigetvár, at Šenkovec, 2016 A plaque in honor to Zrinski for the 450th anniversary of the siege of Szigetvár, at Čakovec, 2016

A plaque in honor to Zrinski for the 450th anniversary of the siege of Szigetvár, at Čakovec, 2016

Annotations

- There never existed a historical person with a name of Nikola Šubić Zrinski neither did his family members call themselves as "Šubić Zrinski".[2][3] In the historical sources, he is simply known as Nikola Zrinski i.e. Miklós Zrínyi which in the English language translates as Nikola of Zrin. In Croatia besides the real name he is also known as Nikola Šubić Zrinski, which is a 19th-century variation popularized by the same-titled opera,[2] while in Croatia and Hungary as Nikola Zrinski Sigetski and Miklós Zrínyi Szigetvári (in English language Nicholas of Zrin of Szigetvár).[4]

References

Notes

- Pravopisna komisija (1960). Pravopis srpskohrvatskoga književnog jezika. Zagreb: Matica srpska, Matica hrvatska.

- Mirnik, Ivan (2004), "Luc Orešković. Les Frangipani. Un exemple de la réputation des lignages au XVIIe siècle en Europe. Cahiers Croates. Hors-serie 1, 2003. Izdanje: Almae matris croaticae alumni (A.M.C.A.). Odgovoran za publikaciju: Vlatko Marić. Mali oktav, str. 151, 33 sl., 1 genealoška shema, 7 shematskih prikaza međusobnih odnosa, tablice s opisima grbova na 7 str. ISSN nedostaje (Review article)", Historical Contributions (in Croatian), Croatian Institute of History, 27 (27): 173 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske

- Inoslav Bešker (7 September 2018). "450. Godišnjica bitke kod Sigeta: Sparta je imala svog Leonidu, a mi svoga Zrinskoga" [450. Anniversary of the Battle of Siget: Sparta had its Leonid, and we had our Zrinski] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Zrinski, Nikola IV", Croatian Encyclopedia (in Croatian), Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, 1999–2009, retrieved 19 April 2014

- Timothy Hughes Rare & Early Newspapers, Item 548456. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- Victor-L. Tapie (1972). The Rise and Fall of the Habsburg Monarchy. p. 62.

One of the richest lords of the region, Nicholas Zrinsky, a Croat whose name took the form of Zrinyi in Hungarian...

- Lendvai, Paul (2014). "Zrinyi or Zrinski? One Hero for Two Nations". The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat. Princeton University Press. pp. 126–136. ISBN 978-1-4008-5152-2.

...there is no doubt that his mother-tongue was Croat. On the other hand, Croatia at that time had already been an integral part of Hungary for 400 years, albeit under a special administration. As a member of the high nobility, Zrinyi therefore belonged to the natio Hungarica, the political nation of Hungary which, however, was not an ethnic but a juridico-political category. Zrinyi/Zrinski fell as a Croat nobleman in the fight against the Turks for Emperor Ferdinand, who was at the same time crowned King of Royal Hungary. He died as a Croat for Hungary. At that time his ethnic affiliation had nothing to do with language, as it would in modern Hungary.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. pp. 881–882. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Hrvoje Petrić (2017). "Nikola IV. Šubić Zrinski: O 450. obljetnici njegove pogibije i proglašenju 2016. "Godinom Nikole Šubića Zrinskog"" [Nikola IV. Šubić Zrinski: About 450th anniversary of his death and proclaiming of 2016 the year of Nikola Šubić Zrinski]. Hrvatska revija (in Croatian). Zagreb: Matica hrvatska (3): 29–33. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Zrinski, Nikola". Enciklopedija Leksikografskog zavoda. 6. Zagreb: Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. 1969. p. 744.

- Lieber, Francis (1836). "Zrinyi". Encyclopædia Americana. 13. Desilver, Thomas. p. 345.

- Tracy, James D. (2016). Balkan Wars: Habsburg Croatia, Ottoman Bosnia, and Venetian Dalmatia, 1499–1617. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 102–103, 120, 122, 125–127, 253. ISBN 978-1-4422-1360-9.

- "Zrinski", Croatian Encyclopedia (in Croatian), Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, 1999–2009, retrieved 27 May 2019

- Ferdo Šišić: Povijest Hrvata - Pregled povijesti hrvatskog naroda 1526-1918 - drugi dio, pg. 295

- Dóra Bobory (2009). The Sword and the Crucible. Count Boldizsár Batthyány and Natural Philosophy in Sixteenth-Century Hungary. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 14, 23, 35, 88 145. ISBN 978-1-4438-1093-7.

- Kovács S., Tibor; Négyesi, Lajos; Padányi, József (2017), "Sablja Sigetskog Nikole IV. Zrinskog" [Sabre of Nikola IV. Zrinski of Siget], Podravina: Scientific Multidisciplinary Research Journal (in Croatian), Zagreb: Meridijani, 16 (32): 43–58 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske

- Szilágyi Sándor, ed. (1897). "VII. Chapter: A szigeti hadjárat". A magyar nemzet története: Magyarország három részre oszlásának története (1526–1608) IV: Az ország végleges felosztása 1548-1568. Hungarian Electronic Library (in Hungarian). Budapest: Athenaeum Irodalmi és Nyomdai Rt.

- Shelton, Edward (1867). The book of battles: or, Daring deeds by land and sea. London: Houlston and Wright. pp. 82–83.

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The Sixteenth Century. IV. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. pp. 845–846. ISBN 0-87169-162-0.

- Count Miklos Zrinyi (1508—1566), Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Pernjak, Dejan (2016). "Franjo Črnko: Nikola Zrinski – branitelj Sigeta grada ur. Alojz Jembrih, Hrvatsko književno društvo sv. Jeronima, Zagreb, 2016., 144 str". Kroatologija: časopis Za Hrvatsku Kulturu (in Croatian). Zagreb: University of Zagreb Center for Croatian Studies. 7 (2): 226–229 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske.

- Walton, Jeremy F. (2019). "Sanitizing Szigetvár: On the post-imperial fashioning of nationalist memory". History and Anthropology. Routledge. 30 (4): 434–447. doi:10.1080/02757206.2019.1612388.

- Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2001). Bu Mülkün Sultanları: 36 Osmanlı Padişahi. Oğlak Yayıncılık ve Reklamcılık. p. 141. ISBN 978-975-329-299-3.

- Korunek, Marijana (2014), "Pavlinski samostan u Šenkovcu i grofovi Zrinski" [Pauline monastery in Šenkovec and Counts Zrinski], Croatica Christiana Periodica (in Croatian), Zagreb: The Catholic Faculty of Theology, 38 (73): 51–70 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske

- Book (1867). E. Shelton and C. Jones (ed.). The book of battles; Daring deeds by land and sea. London: Houlston and Wright. pp. 82–83.

- Mirnik, Ivan A. (1992). Srebra Nikole Zrinskog: Gvozdanski rudnici i kovnica novca [Nicholas of Zrin’s silver: The Gvozdansko mines and mint]. Zagreb: Društvo povjesničara umjetnosti Hrvatske (DPUH). p. 13.

- Lengyel, Tünde (2015). "The Chances for a Provincial Cultural Centre: The Case of György. Thurzó, Palatine of Hungary (1567−1616)". In Gábor Almási; Szymon Brzeziński; Ildikó Horn (eds.). A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4438-7297-3.

- Troch, Pieter (2015). Nationalism and Yugoslavia: Education, Yugoslavism and the Balkans before World War II. I.B.Tauris. pp. 83–84, 93, 99, 200. ISBN 978-0-85773-768-7.

- Heuser, Beatrice (2017). "Defeat as Moral Victory: The Historical Experience". In Andrew R. Hom; Cian O'Driscoll; Kurt Mills (eds.). Moral Victories: The Ethics of Winning Wars. OUP Oxford. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-252197-2.

- Leszek Małczak (2017). "Nikola Šubić Zrinski u poljskoj kulturi". In Stjepan Blažetin (ed.). XIII. Međunarodni kroatistički znanstveni skup, zbornik radova. ISBN 978-963-89731-3-9.

- Thomas, David; Chesworth, John A. (2015). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History.: Volume 7. Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa and South America (1500-1600). BRILL. pp. 93, 430, 493. ISBN 978-90-04-29848-4.

- Kidrič, Francè (2013), "Budina, Samuel (med 1540 in 1550–po 1571)", Slovenska biografija, Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti, Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU

- Josip Vončina, ed. (1976). Pet stoljeća hrvatske književnosti, knjiga 17: Izabrana djela - Zrinski, Frankopan, Vitezović. Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, Zora. pp. 7–24.

- "Miklós Zrínyi". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- Ivana Sabljak (2007). "U povodu 660 godina od bilježenja imena plemićke obitelji Zrinski: Dva brata i jedna Sirena". Vijenac (in Croatian). Zagreb: Matica hrvatska (349). Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Thomas, David; Chesworth, John A. (2017). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Volume 10 Ottoman and Safavid Empires (1600-1700). BRILL. pp. 340–342. ISBN 978-90-04-34604-8.

- Kolumbić, Nikica (1970). "Vitezovićev lirski doživljaj sigetske tragedije". Senjski Zbornik: Prilozi Za Geografiju, Etnologiju, Gospodarstvo, Povijest I Kulturu (in Croatian). Senj: Gradski muzej Senj i Senjsko muzejsko društvo. 4 (1): 281–299 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske.

- Bratulić, Josip (1996). "Trnava i Požun (Bratislava) i hrvatska tiskana knjiga XVII. i XVIII. stoljeća". Croatica: časopis Za Hrvatski Jezik, Književnost I Kulturu (in Croatian). Zagreb: Department of Croatian language and literature at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. 26 (42–43–44): 83 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske.

- Pintér, Márta Zsuzsanna (2009). "Zrinius ad Sigethum. Théorie dramatique et pratique du théâtre dans l'oeuvre d'Andreas Friz S.J.". In Wilhelm Kühlmann, Gábor Tüskés (ed.). Militia et Litterae: Die beiden Niklaus Zrìnyi und Europa. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 242–257. ISBN 978-3-484-36641-1.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Jagoda Martinčević (15 August 2016). "Nikolu Šubića Zrinskog nije napisao Zajc, nego stanoviti August Abramović Adelburg..." (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Shiba, Nobuhiro (2008). "Jedan odlomak iz povijesti suradnje Japana i Hrvatske: Hrvatska pjesma "U boj" i japanski muški zbor" [An episode from the history of cooperation between Japan and Croatia: Croatian song “U boj” and Japanese male choirs]. Povijest U Nastavi (in Croatian). Zagreb: Društvo za hrvatsku povjesnicu. VI (12 (2)): 167–176 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske.

- Fatović-Ferenčić, Stella; Ferber-Bogdan, Jasenka (2003). "Tragom slike Nikole Šubića Zrinskog: kronologija kraljevske dvorske ljekarne K Zrinjskomu" [Tracing the Painting of Nikola Šubić Zrinski: the Chronology of Royal Pharmacy K Zrinjskomu]. Medicus (in Croatian). Zagreb: Pliva Hrvatska. 12 (1): 143–150 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske.

- Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck (1981). Das Heeresgeschichtliche Museum Wien. Das Museum und seine Repräsentationsräume. Salzburg: Kiesel Verlag. p. 30. ISBN 3-7023-0113-5.

- Varga, Szabolcs (2018). "Nikola Zrinski Sigetski – Nikola Šubić Zrinski. Revidiranje zajedničke hrvatsko-mađarske povijesti u 21. stoljeću" [Szigetvári Zrínyi Miklós – Nikola Šubić Zrinski. Revising Common Croatian and Hungarian History in the Twenty First Century]. Zbornik Odsjeka Za Povijesne Znanosti Zavoda Za Povijesne I Društvene Znanosti Hrvatske Akademije Znanosti I Umjetnosti (in Croatian). Zagreb. 36: 81–92. doi:10.21857/mzvkptz7r9 – via Hrčak - Portal znanstvenih časopisa Republike Hrvatske.

- Zakon o odlikovanjima i priznanjima Republike Hrvatske Archived 2007-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, Narodne novine 20/95 ("Law on Decorations"); accessed 1 September 2016. (in Croatian)

Sources

- Treaty of peace with Germany: Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Relations... ...signed at Versailles on June 28, 1919, and submitted to the Senate on July 10, 1919 - "the Slavs rescued them from a strangle-hold, namely, Nicholas Zrinsky and John Sobieski. one a Croatian and the other a Pole."

- Further reading

- Josip Bratulić, Vladimir Lončarević, Božidar Petrač, Nikola Šubić Zrinski u hrvatskom stihu (in Croatian, 2016), Croatian Writers' Association, Zagreb, pages 756, ISBN 978-953-278-235-6

- Szabolcs Varga, Leónidasz a végvidéken. Zrínyi Miklós (1508–1566) (in Hungarian, 2016), Kronosz, Pécs–Budapest, 2016, pages 280, ISBN 978-615-549-783-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nikola Šubić Zrinski. |

- Zrinyi, Nicolaus at the Deutsche Biographie

- Zrinski's sabre at the Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Zrinski's helmet at the Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Zrinski's funeral picture at the Hungarian National Museum

- Croatian documentary episode Nikola Šubić Zrinski of TV series "Hrvatski Velikani" by Hrvatska Radiotelevizija, 2016

Nikola IV Zrinski House of Zrinski Born: 1507–1508 Died: 7 September 1566 | ||

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Petar Keglević |

Ban of Croatia 1542–1556 |

Succeeded by Péter Erdődy |

| Preceded by Gábor Perényi |

Master of the treasury 1557–1566 |

Succeeded by Juraj Zrinski |