Zoltán Huszárik

Zoltán Huszárik (born József Zoltán Huszárik, May 14, 1931 – October 15, 1981) was an influential Hungarian film director, screenwriter, visual artist and occasional actor, an acclaimed auteur of the European modern art film.[4]

Zoltán Huszárik | |

|---|---|

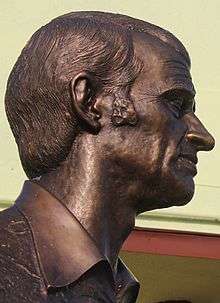

Bust of Zoltan Huszarik, Domony | |

| Born | May 14, 1931 |

| Died | October 15, 1981 |

| Years active | 1959 — 1980 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Kata Huszárik (b. 1971 – mother Anna Nagy) |

Huszárik was born in the small village of Domony,[4] Hungary. His father died when he was two years old. Being an only child, Huszárik had an adoring relationship with his widowed mother. His background had a great influence on his work.

He was accepted to the Hungarian School of Film- and Theatrical Arts, but was expelled in 1952 because his family was blamed to be Kulaks. He took on different jobs, when—after a seven-year hiatus—he was again accepted to the film school in 1959. In the same year he made his first student film, a short entitled Játék (Game) about two prisoners playing chess with the shadow of their bars when the sun shines unto their cell. Huszárik's graduation film was another short entitled Groteszk (Grotesque) in 1963 about a strange train voyage of an artist carrying his own picture.

Huszárik made his first professional short film in 1965 at Béla Balázs Studios entitled Elégia (Elegy). This 20-minute experimental short film was generally acclaimed as being the starting point of a new visual style in Hungarian filmmaking. Often called a "film poem" or a "film symphonie" Huszárik's masterpiece consists of montages of horses from the dawn of time to the modern times from cave paintings to horse races, mourning the loss of these creatures and their service to mankind, starting as free animals and becoming slaughterhouse victims. The film is generally regarded as an allegory to the human fate.

Huszárik made another experimental short film called Capriccio (about snowmen melting in the spring as an allegory to man's ultimate fate - death) and a short documentary on Hungarian-born artist Amerigo Tot, both in 1969. He also directed several state-financed educational short films in this period.

In 1971 Huszárik finished his first feature-length work Szindbád (Sinbad), a highly stylized adaptation of early 20th century author Gyula Krúdy's short stories. The film depicts the life and memories of traveler and womanizer Szindbád (played by Zoltán Latinovits), who tries to recover his lost love before he dies. The film which covers time and memory in an unusual way, was praised by critics and was a commercial success upon its release and is generally regarded now as one of the best works of Hungarian cinema.

Huszárik made two experimental shorts in 1971 and 1976, entitled Tisztelet az öregasszonyoknak (Homage to Old Ladies) and A Piacere (As You Like It), respectively. The first is a homage to the old country widows whose husbands died in World War II and live their lives according to daily tasks and regulations until they die (which is mainly inspired by Huszárik's own mother). The second is a study of death in its various forms, including a gypsy "merry funeral" and stock footage of bombings and concentration camps in WWII.

The second (and last) feature-length film of Huszárik was made after a five-year struggle. Csontváry depicts the life of Hungarian artist Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka and an actor playing him in a film (both played by Bulgarian actor Ichak Finci), with the two men' lives interacting with each other. After the death of Latinovits, who was the original choice for the dual role, the film went on through several re-writes, re-shoots, casting and budget problems, finally ending up as the most expensive Hungarian production at the time. The film was finally completed and released in 1980. It was a huge failure with the public and critics also bashed it. Huszárik who was greatly exhausted, depressed and an alcoholic at the time committed suicide in 1981 at the age of 50.

Huszárik originally wanted to be a visual artist. He made several paintings, drawings and other pieces of art during his lifetime. He also took smaller acting jobs in the films of fellow Hungarian directors, including István Szabó's Budapesti mesék (Budapest Tales). His daughter, Kata Huszárik is an acclaimed actress.

Filmography

- 1959: Játék (Game) (short, student film)[5]

- 1963: Groteszk (Grotesque) (short, student film)[5]

- 1965: Elégia (Elegy) (short)[5]

- 1967: Egy mentőorvos naplójából (Diary of an Ambulance Doctor) (short, documentary)[5]

- 1967: Maszkot akarok (I Want a Mask) (TV, short, documentary)

- 1968: Heten a hegy ellen (Seven against the Mountain) (TV, short, documentary)

- 1968: Hegyi kiképzés (Mountain Training) (short, documentary)

- 1968: Ugye te is akarod? (You'll Also Like to Do It?) (short, documentary)[5]

- 1969: Amerigo Tot (short, documentary)[5]

- 1969: Capriccio (short)[5]

- 1971: Szindbád (Sinbad)[5]

- 1971: Tisztelet az öregasszonyoknak (Homage to Old Ladies) (short)[5]

- 1976: A Piacere (As You Like It) (short)[5]

- 1980: Csontváry[5]

Source material

- An Eastern European Picture-writer (Egy kelet-európai képíró) Article of Zalán Vince in the Hungarian Filmvilág (Filmworld) magazine, January 1982.

- Commemorative program on the Magyar Televízió Hungarian Television on the 75th anniversary of the birth of Huszarik (May 2006)

References

- János Eifert (12 August 2011). "Kedvesem! Boldog születésnapot!". eifert.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- L. Horváth Katalin (2011-10-28). "Minden idők egyik legszebb magyar filmje 40 éves". HVG.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- Zalán Magda (1982). "Fekete-fehér elégia". Új Látóhatár (in Hungarian). XXXIII. (3–4): 417–425.

- "Huszárik Zoltán, Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon". Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- "Huszárik Zoltán a port.hu oldalán". Retrieved 2010-02-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zoltán Huszárik. |

- Zoltán Huszárik on IMDb

- Victoria Loomes Szinbád: Hungary's finest Casanova Girls Do Film, December 30, 2011

- Szendi Horváth Éva A new generation in Hungarian cinematography Diplomata (Diplomatic Magazine), 2009. (10. évf.) 3. sz. 40-41. p.